Indian reservation

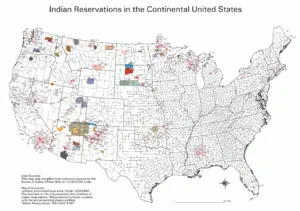

Indian reservation in the United States is an area of land managed by a Native American tribe under the United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs. Historically, reservations have been established on every continent with the exception of unpopulated Antarctica. There are more than 300 Indian reservations in the United States. They were all established either by treaty or decree.

Indian removal was a policy pursued intermittently by American presidents early in the nineteenth century, but more aggressively pursued by President Andrew Jackson after the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The act led to the creation of Indian territory, the general borders of which were set by the Indian Intercourse Act of 1834. Eventually, the Indian Appropriations Act of 1851 authorized the establishment of legally recognized reservations in the U.S. While in the twenty-first century reservation travel is unrestricted, at the time of establishment indigenous residents were forbidden from traveling outside the reservation boundaries.

Treaty language generally guaranteed reservation land to belong to a particular tribe "in perpetuity." However, most tribes found their original treaties amended, allotting smaller and smaller portions of land to them. The Dawes Act of 1887, also known as the General Allotment Act, resulted in further depriving the Native Americans of their lands and resources through a system of fragmentation that has rendered much of reservation land unusable. It also had a catastrophic effect upon native culture, forcing the move from a clan system to a family system and imposing a patrilineal nuclear household onto many traditional matrilineal Native societies.

Most reservations have suffered high rates of poverty, unemployment, and substance abuse. However in recent years they have come to represent an oasis of tribal and cultural identity, providing a base of support for the expansion of Native American rights. While the history of this system has been tragic, the Indian reservation has protected the indigenous peoples from complete assimilation and loss of identity.

Historical background

In order to more fully understand the process through which Native Americans were "placed" in designated lands known as reservations, it is necessary to understand the mentality of white America at that time.

The concept of Manifest Destiny was a nineteenth-century belief that the United States had a mission to expand westward across the North American continent, spreading its form of democracy, freedom, and culture. Many believed the mission to be divinely inspired while others felt it more as an altruistic right to expand the territory of liberty.[1]

Manifest Destiny had serious consequences for Native Americans, since continental expansion usually meant the occupation of Native American land. The United States continued the European practice of recognizing only limited land rights of indigenous peoples. In a policy formulated largely by Henry Knox, Secretary of War in the Washington Administration, the U.S. government initially sought to expand into the west only through the legal purchase of Native American land in treaties. "Indians" were encouraged to sell their vast tribal lands and become "civilized," which meant (among other things) for Native American men to abandon hunting and become farmers, and for their society to reorganize around the family unit rather than the clan or tribe. Advocates of "civilization" programs believed that the process would greatly reduce the amount of land needed by the Indians, thereby making more land available for purchase by white Americans. Thomas Jefferson believed that while American Indians were the intellectual equals of whites, it was necessary that they live like the whites or inevitably be pushed aside by them. Jefferson's belief, rooted in Enlightenment thinking, which held that whites and Native Americans would merge to create a single nation, did not last his lifetime. Jefferson grew to believe that the natives should emigrate across the Mississippi River and maintain a separate society, an idea made possible by the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.

In the age of Manifest Destiny, this idea, which came to be known as "Indian Removal," gained ground. Although some humanitarian advocates of removal believed that Native tribes would be better off moving away from whites, an increasing number of Americans regarded the natives as nothing more than "savages" who stood in the way of American expansion. As historian Reginald Horsman argued in his influential study Race and Manifest Destiny,[2] racial rhetoric increased during the era of Manifest Destiny. Americans increasingly believed that Native Americans would fade away as the United States expanded. As an example, this idea was reflected in the work of one of America's first great historians, Francis Parkman, whose landmark book The Conspiracy of Pontiac was published in 1851. Parkman wrote that Indians were "destined to melt and vanish before the advancing waves of Anglo-American power, which now rolled westward unchecked and unopposed".[3]

First land acquisitions

As the new nation expanded westward, the U.S. government's initial means of acquiring land was through a treaty-purchase process. There were various reasons the tribes agreed to signing treaties, which in most cases they could not read, and whose translations were often flawed. In numerous cases, government representatives procured the signatures of those not authorized to speak for the tribes, yet required them, through force, to obey the conditions of the ill-begotten agreements. In other cases, tribes agreed to treaties in order to appease the government in the hopes of retaining some of their land, and wanted to protect themselves from white harassment. The signing of a treaty often followed a resignation of defeat and served as a last resort effort to bring peace.

While the government initially sought to secure Native lands through treaty-purchase, eventually additional means were employed, such as "discovery," right of conquest, coercion, and military force. Reservations were an outgrowth of these acquisitions. Prior to the American Revolution, various colonies created unofficial reservations, some of which were later formally recognized as "Indian reservations." The first reserve in North America was established on August 1, 1758 in Burlington County New Jersey by the New Jersey Colonial Assembly, and was designated a "permanent home" for the Lenni-Lenape tribe.

In 1775 the Second Continental Congress established an Indian Department to deal with matters relating to tribal issues. Following the nation's independence, a national policy of Indian administration by Constitutional mandate was adopted. Congress was granted plenary powers over Indian affairs in treaties, trade, warfare, welfare, and the procurement of Indian lands for public purposes.[4]

The establishment of federal Indian reservations began after 1778 and initially conferred to the occupying tribe(s) recognized title over lands and the resources within their boundaries. In addition, protection in exchange for land cessions was promised; however well-meaning this might have been, it was essentially impossible to implement.

In 1823 the Supreme Court handed down a decision (Johnson v. M'Intosh), which stated that Indians could occupy lands within the United States, but could not hold title to those lands. This was because their "right of occupancy" was subordinate to the United States' "right of discovery."[5]

The Indian Removal Act

Indian resistance to voluntary removal and a decreasing willingness to sell land via treaty led to the Indian Removal Act, part of a government policy known as Indian removal, which was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson on May 26, 1830.[6] While the isolation and concentration of American Indians began years earlier, its first legal justification was in this Removal Act.

The Removal Act was strongly supported in the South, where states were eager to gain access to lands inhabited by the "Five Civilized Tribes." (The Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole were considered civilized by white settlers during that time period because they adopted many of the colonists' customs and had generally good relations with their neighbors.) In particular, Georgia was involved in a contentious jurisdictional dispute with the Cherokee nation. President Jackson hoped removal would resolve the Georgia crisis.

The Indian Removal Act was also very controversial. While Indian removal was, in theory, supposed to be voluntary, in practice great pressure was put on Indian leaders to sign removal treaties. Most observers, whether they were in favor of the Indian removal policy or not, realized that the passage of the act meant the inevitable removal of most Indians from the states. Some Native American leaders who had previously resisted removal eventually began to reconsider their positions, especially after Jackson's landslide reelection in 1832.

Most white Americans favored the passage of the Indian Removal Act, though there was significant opposition. Many Christian missionaries, most notably missionary organizer Jeremiah Evarts, agitated against passage of the Act. In Congress, New Jersey Senator Theodore Frelinghuysen and Congressman David Crockett of Tennessee spoke out against the legislation. The Removal Act was passed following bitter debate in Congress.

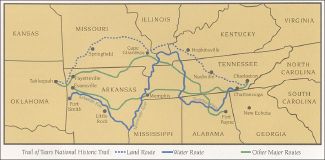

The Removal Act paved the way for the reluctant—and often forcible—emigration of tens of thousands of American Indians to the West. The first removal treaty signed after the Removal Act was the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek on September 27, 1830, in which Choctaws in Mississippi ceded land east of the river in exchange for payment and land in the West. The Treaty of New Echota (signed in 1835) resulted in the removal of the Cherokee via the Trail of Tears. The Seminoles did not leave peacefully as did other tribes; along with fugitive slaves they resisted the removal. The Second Seminole War lasted from 1835 to 1842 and resulted in the forced removal of Seminoles, only a small group of "renegades" remained on or near their traditional lands. Nearly 3,000 were killed during the effort.[7] Other treaties with dozens of other tribes resulted in their placement on lands often far from their homes, requiring treks of hundreds of miles, often in unforgivable weather.

The Indian Appropriations Act

In 1851, the United States Congress passed the Indian Appropriations Act which authorized the creation of Indian reservations in modern day Oklahoma. Relations between settlers and natives had grown increasingly worse as the settlers encroached on territory and natural resources in the West.

President Ulysses S. Grant pursued a stated "Peace Policy" as a possible solution to the conflict. The policy included a reorganization of the Indian Service, with the goal of relocating various tribes from their ancestral homes to parcels of lands established specifically for their inhabitation. The policy called for the replacement of government officials by religious men, nominated by churches, to oversee the Indian agencies on reservations in order to teach Christianity to the native tribes.

In many cases the lands granted to tribes were hostile to agricultural cultivation, leaving many tribes who accepted the policy in a state bordering on starvation.

Reservation treaties sometimes included stipend agreements, in which the federal government promised to grant a certain amount of goods to a tribe yearly. The implementation of the policy was erratic, however, and in many cases the stipend goods were not delivered.

Controversy

The policy was controversial from the start. Reservations were generally established by executive order. In many cases, white settlers objected to the size of land parcels, which were subsequently reduced. A report submitted to Congress in 1868 found widespread corruption among the federal Native American agencies and generally poor conditions among the relocated tribes.

Many tribes ignored the relocation orders at first and were forced onto their new limited land parcels. Enforcement of the policy required the United States Army to restrict the movements of various tribes. The pursuit of tribes in order to force them back onto reservations led to a number of Native American Wars. The most well known conflict was the Sioux War on the northern Great Plains, between 1876 and 1881, which included the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Other famous wars in this regard included the Nez Perce War.

By the late 1870s, the policy established by President Grant was regarded as a failure, primarily because it had resulted in some of the bloodiest wars between Native Americans and the United States. By 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes began phasing out the policy, and by 1882 all religious organizations had relinquished their authority to the federal Indian agency.

The Dawes Act

On February 8, 1887, Congress undertook a significant change in reservation policy by the passage of the Dawes Act, named after its sponsor, U.S. Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts. Also known as the General Allotment Act, it ended the general policy of granting land parcels to tribes as-a-whole by granting small parcels of land to individual tribe members. In some cases, for example the Umatilla Indian Reservation, after the individual parcels were granted out of reservation land, the reservation area was reduced by giving the excess land to white settlers. The act was amended in 1891 and again in 1906 by the Burke Act. The individual allotment policy continued until 1934, when it was terminated by the Indian Reorganization Act.

Effects

The land granted to most allottees was not sufficient for economic viability, and division of land between heirs upon the allottees' deaths resulted in land fractionation. Most allotment land, which could be sold after a statutory period of 25 years, was eventually sold to non-Native buyers at bargain prices. Additionally, land deemed to be "surplus" beyond what was needed for allotment was opened to white settlers, though the profits from the sales of these lands were often invested in programs purported to aid the American Indians. Native Americans lost, over the 47 years of the Act's life, about 90 million acres (360,000 km²) of treaty land, or about two-thirds of the 1887 land base. About 90,000 Indians were made landless.[8]

By dividing reservation lands into privately-owned parcels, legislators hoped to complete the assimilation process by forcing the deterioration of the communal life-style of the Native societies and imposing Western-oriented values of strengthening the nuclear family and values of economic dependency strictly within this small household unit.[9]

The Dawes Act, with its emphasis on individual land ownership, also had a negative impact on the unity, self-government, and culture of Indian tribes.[8] The allotment policy depleted the land base, ending hunting as a means of subsistence. According to Victorian ideals, the men were forced into the fields to take on the woman's role and the women were domesticated. Thus this Act imposed a patrilineal nuclear household onto many traditional matrilineal Native societies.

In 1906 the Burke Act (also known as the forced patenting act) further amended the GAA to give the Secretary of the Interior the power to issue allotees a patent in fee simple to people classified ‘competent and capable.’ The criteria for this determination is unclear but meant that allotees deemed ‘competent’ by the Secretary of the Interior would have their land taken out of trust status, subject to taxation, and could be sold by the allottee. The allotted lands of Indians determined to be incompetent by the Secretary of the Interior were automatically leased out by the Federal Government.[10] The use of competence opens up the categorization, making it much more subjective and thus increasing the exclusionary power of the Secretary of Interior. Although this act gives power to the allottee to decide whether to keep or sell the land, provided the harsh economic reality of the time, lack of access to credit and markets, liquidation of Indian lands was almost inevitable. It was known by the department of interior that virtually 95 percent of fee patented land would eventually be sold to whites.[11]

In 1926, Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work commissioned a study of federal administration of Indian policy and the condition of Indian people. The Problem of Indian Administration - commonly known as the Meriam Report after the study's director, Lewis Meriam - documented fraud and misappropriation by government agents. In particular, the Meriam Report found that the General Allotment Act had been used to illegally deprive Native Americans of their land rights.[12] After considerable debate, Congress terminated the allotment process under the Dawes Act by enacting the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 ("Wheeler-Howard Act"). (However, the allotment process in Alaska under the separate Alaska Native Allotment Act continued until its revocation in 1993 by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.)

Despite termination of the allotment process in 1934, effects of the General Allotment Act continue into the present. For example, one provision of the Act was the establishment of a trust fund, administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, to collect and distribute revenues from oil, mineral, timber, farming, and grazing leases on Native American lands. The BIA's alleged improper management of the trust fund resulted in litigation, in particular the ongoing case Cobell v. Kempthorne, to force a proper accounting of revenues.

Angie Debo's landmark work, And Still the Waters Run: The Betrayal of the Five Civilized Tribes (completed 1936, published 1940), detailed how the allotment policy of the Dawes Act (as later extended to apply to the Five Civilized Tribes through such devices as the Dawes Commission and the Curtis Act of 1898) was systematically manipulated to deprive the Native Americans of their lands and resources.[13] In the words of historian Ellen Fitzpatrick, Debo's book "advanced a crushing analysis of the corruption, moral depravity, and criminal activity that underlay white administration and execution of the allotment policy."[14]

The Indian Reorganization Act

The Indian Reorganization Act of June 18, 1934, also known as the Wheeler-Howard Act or informally, the Indian New Deal, was a U.S. federal legislation which secured certain rights to Native Americans, including Alaska Natives.[15] These included a reversal of the Dawes Act's privatization of common holdings of American Indians and a return to local self-government on a tribal basis. The Act also restored to Native Americans the management of their assets (being mainly land) and included provisions intended to create a sound economic foundation for the inhabitants of Indian reservations. Section 18 of the IRA conditions application of the IRA on a majority vote of the affected Indian nation or tribe within one year of the effective date of the act (25 U.S.C. 478). The IRA was perhaps the most significant initiative of John Collier Sr., Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs from 1933 to 1945.

The act did not require tribes to adopt a constitution. However, if the tribe chose to do so, the constitution had to:

- allow the tribal council to employ legal counsel;

- prohibit the tribal council from engaging any land transitions without majority approval of the tribe; and,

- authorize the tribal council to negotiate with the Federal, State, and local governments.

The act slowed the practice of assigning tribal lands to individual tribal members and reduced the loss, through the practice of checkerboard land sales to non-members within tribal areas, of native holdings. Owing to this Act and to other actions of federal courts and the government, over two million acres (8,000 km²) of land were returned to various tribes in the first 20 years after passage of the act.

In 1954, the United States Department of Interior began implementing the termination and relocation phases of the Act. Among other effects, termination resulted in the legal dismantling of 61 tribal nations within the United States.

This abrupt change in federal policy created a legal morass by authorizing the existence of two governmental systems, state and tribal, with completely different legislative, administrative, enforcement, and judicial systems in the same geographical area.[16] There have been numerous court cases since the implementation of this act, challenging its constitutionality.

Twenty first century

Today there are about 310 Indian reservations in the United States, with a collective geographical area of 52.7 million acres (82,343.75 mi²)[17], representing 2.21 percent of the area of the United States (2,379,400,204 acres; 3,717,812.82 mi²). Not all of the country's 562 recognized tribes[17] have a reservation—some tribes have more than one reservation, others have none. In addition, because of past land sales and allotments, most reservations are severely fragmented to the point of being non-usable. Each piece of tribal, trust, and privately held land is a separate enclave.

The Navajo tribe owns the largest amount of land (15,573,760 acres; 24,334 mi²), roughly the size of West Virginia.[18] There are twelve Indian reservations that are larger than the state of Rhode Island (776,960 acres; 1,214 mi²) and nine reservations larger than Delaware (1,316,480 acres; 2,057 mi²). Most are significantly smaller; about two-thirds of them encompass an area less than 32,000 acres (50 mi²).[18] Reservations are unevenly distributed throughout the country with some states having none. Notably, Missouri and Arkansas are the only two states that are a part of the contiguous 48 states west of the Mississippi River without Indian reservations.

The tribal council, not the local or federal government, has jurisdiction over reservations. Different reservations have different systems of government, which may or may not replicate the forms of government found outside the reservation. These conflicting jurisdictions and rules, as established by the Indian Reorganization Act, have resulted in confusion, frustration, antagonism, and litigation that severely reduces the quality of life, the potential for economic development, and the prospect for social harmony on reservations.[16]

Legacy

The forced cultural loss and fragmented land base resulting from the General Allotment Act, compounded by the economic, social, and physical isolation from the majority society, has produced extreme poverty, high unemployment, unstable families, low rates of high school graduation, and high rates of alcoholism and/or drug abuse and crime on many reservations.[19]

While reservation life has historically been faced with challenges, it has also offered a strong sense of place and cultural identity, supporting a resurgence in tribal identity and a renaissance of traditions. They have emerged as the focal point for the retention of unique cultural identities and for issues of sovereignty and self-determination. They provide a geographical and political platform to expand Native American rights, and serve as a home-base for those who have moved away. While they can be a reminder of the tragedies of American expansionism, they are viewed by many as the last remaining stronghold of sovereignty and cultural traditions, ensuring the perpetuation of Native American survival.[4]

Notes

- ↑ Michael T. Lubragge. March 6, 2003. From Revolution to Reconstruction-Manifest Destiny University of Groningen. Retrieved January 27, 2009.

- ↑ Reginald Horsman. 1981. Race and manifest destiny: the origins of American racial anglo-saxonism. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. (ISBN 9780674745728)

- ↑ Francis Parkman. 1851. History of the conspiracy of Pontiac, and the War of the North American Tribes against the English Colonies after the Conquest of Canada. Boston: Charles C. Little.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Answers Corporation. 2008. Indian Reservations Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- ↑ Public Broadcasting Service. People & Events: Indian removal, 1814 - 1858 Retrieved January 27, 2009.

- ↑ Francis Paul Prucha. 1984. The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians, Volume I Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p 206.

- ↑ Eric Foner.2004. Give me liberty!: an American history. New York: W.W. Norton. (ISBN 9780393978728)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 David S. Case and David A. Voluck. 2002. Alaska natives and American laws. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press. (ISBN 9781889963082)

- ↑ Arrell M. Gibson. 1988. "Indian Land Transfers." Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 04, pp. 211-229. Ed. Wilcomb E. Washburn.

- ↑ David Bartecchi. February 19, 2007. The History of "Competency" as a Tool to Control Native American Lands Village Earth - Pine Ridge Project. Retrieved January 27, 2009.

- ↑ Paul Robertson. 2002. The power of the land: identity, ethnicity, and class among the Oglala Lakota. New York: Routledge. (ISBN 9780815335917)

- ↑ Brookings Institution, and Lewis Meriam. 1928. The problem of Indian administration; report of a survey made at the request of Hubert Work, Secretary of the Interior, and submitted to him, February 21, 1928. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

- ↑ Angie Debo. 1991. And still the waters run: the betrayal of the five civilized tribes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press. (ISBN 0691046158.)

- ↑ Ellen Fitzpatrick. 2002. History's memory: writing America's past, 1880-1980. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. (ISBN 067401605X.) p. 133, Google Books' online excerptRetrieved January 27, 2009.

- ↑ Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. The Indian Reorganization Act (W'heeler-Howard Act) - June 18, 1934 Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Smith, Darrel. June 1997. Indian Reservations: America's Model of Destruction Citizens Equal Rights Alliance. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Bureau of Indian Affairs. Quick Facts Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Klaus Frantz. 1999. Indian reservations in the United States: territory, sovereignty, and socioeconomic change. University of Chicago geography research paper, 242. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226260891

- ↑ Gary D. Sandefur. American Indian reservations: The first underclass areas? Institute for Research on Poverty at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Center for Investigative Reporting. November 14, 2008. No Justice Out Here Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. The Indian Reorganization Act (W'heeler-Howard Act) - June 18, 1934 Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Debo, Angie. 1991. And still the waters run: the betrayal of the five civilized tribes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press. ISBN 0691046158.

- Francis, David R. April 23, 2004. Gambling on the Reservation Christian Science Monitor Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Frazier, Ian. 2000. On the rez. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374226381

- Olund, E. N. 2002. "Public Domesticity during the Indian Reform Era; or, Mrs. Jackson is induced to go to Washington." GENDER PLACE AND CULTURE. 9: 153-166. OCLC 196633589

- O'Neill, Terry. 2002. The Indian reservation system. San Diego: Greenhaven Press. ISBN 9780737707151

- Smith, Darrel. June 1997. Indian Reservations: America's Model of Destruction Citizens Equal Rights Alliance. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- Stremlau, Rose. 2005. "To Domesticate and Civilize Wild Indians: Allotment and the Campaign to Reform Indian Families, 1875-1887." Journal of Family History. 30 (3): 265-286.

- The Denver Post. November 21, 2007. Indian Justice Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- U.S. Census Bureau, Geographic Areas Reference manual. Chapter 5: American Indian and Alaska Native Areas Retrieved January 26, 2009.

External links

All Links Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- BIA full-size map of Indian reservations in the continental United States

- BIA index to map of Indian reservations in the continental United States

- US Census tallies for Indian reservations

- FEMA: Federally recognized Indian reservations

- Tribal Leaders Directory

- Native American Technical Corrections Act of 2003

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Indian_reservation history

- Indian_Removal_Act history

- Indian_Reorganization_Act history

- Dawes_Act history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.