Difference between revisions of "Egyptian hieroglyphs" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (74 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{copyedited}} | |

| + | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Linguistics]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Infobox Writing system | ||

|name=Egyptian hieroglyphs | |name=Egyptian hieroglyphs | ||

|type=[[logogram|logography]] | |type=[[logogram|logography]] | ||

|typedesc=usable as an [[abjad]] | |typedesc=usable as an [[abjad]] | ||

| − | |time=3200 | + | |time=3200 B.C.E. – 400 C.E. |

|languages=[[Egyptian language]] | |languages=[[Egyptian language]] | ||

|fam1=([[History of writing#Proto-writing|Proto-writing]]) | |fam1=([[History of writing#Proto-writing|Proto-writing]]) | ||

|children=[[Hieratic]], [[demotic (Egyptian)|Demotic]], [[Meroitic script|Meroitic]], [[Middle Bronze Age alphabets]] | |children=[[Hieratic]], [[demotic (Egyptian)|Demotic]], [[Meroitic script|Meroitic]], [[Middle Bronze Age alphabets]] | ||

| − | |iso15924=Egyp<!-- N.B.: The code is "Egyp" without the letter "t" | + | |iso15924=Egyp<!-- N.B.: The code is "Egyp" without the letter "t."—> |

| − | }}[[ | + | }} |

| − | + | '''Egyptian hieroglyphs''' are a formal [[writing system]] used by the [[ancient Egypt]]ians, and are perhaps the most widely recognized form of [[hieroglyph]]ic writing in the world. The term "hieroglyph" originally referred only to Egyptian hieroglyphs, but has now been expanded to include other hieroglyphic scripts, such as [[Cretan hieroglyphs|Cretan]], [[Luwian]], [[Maya script|Mayan]], and [[Mi'kmaq]]. The Egyptians used hieroglyphs mainly for formal, religious inscriptions (hence their name, "the god’s words"). Egyptian glyphs, like those of many other hieroglyphic scripts, often consist of recognizable objects such as the [[sun]] or a [[bird]], and incorporate a combination of [[logograph]]ic and [[phonetic]] elements. | |

| − | [[ | + | {{toc}} |

| + | Egyptian hieroglyphs constitute one of the oldest known writing systems in the world. Developed from pictures that [[symbol]]ized well known objects, they allowed those in authority to document religious teachings as well as edicts from the [[pharoah]]. In this form the hieroglyphs were generally inscribed in permanent materials such as stone, and thus numerous examples of [[stele|stelae]] and inscriptions on [[tomb]]s have been discovered by [[archaeologist]]s while excavating sites of importance to the ancient Egyptian culture. Contemporaneously, the [[hieratic]] script was developed to allow easier writing using [[ink]] on [[papyrus]] and later the [[demotic (Egyptian)|demotic]] script was developed for secular use. It is through the use of this script that Egyptian hieroglyphs could be deciphered, as the [[Rosetta stone]] contains inscriptions of the same text in these scripts and [[Greek language|Greek]]. Thus, it is now possible to know much about ancient Egyptian culture from thousands of years past through their hieroglyphic writing. Given the significance of this culture in human history, such understanding is of great value. | ||

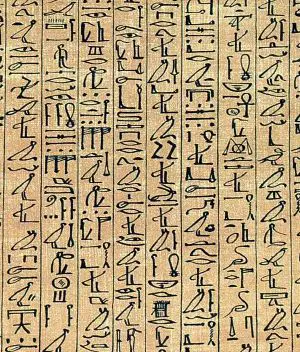

| + | [[Image:Papyrus Ani curs hiero.jpg|thumb|right|A section of the [[Papyrus of Ani]] showing cursive hieroglyphs.]] | ||

| − | + | ==Etymology== | |

| + | The word "[[hieroglyph]]" derives from the [[Greek language|Greek]] words ἱερός ''(hierós)'': "Sacred" and γλύφειν ''(glúphein)'': "To carve" or "to write," as in the term "[[glyph]]." This was translated from the Egyptian phrase "the god’s words," a phrase derived from the Egyptian practice of using hieroglyphic writing predominantly for religious or sacred purposes. | ||

| − | + | The term "hieroglyphics," used as a noun, was once common but now denotes more informal usage. In academic circles, the term "hieroglyphs" has replaced "hieroglyphic" to refer to both the language as a whole and the individual characters that compose it. "Hieroglyphic" is still used as an adjective (as in a hieroglyphic writing system). | |

| − | The | ||

== History and evolution== | == History and evolution== | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[Image:NarmerPalette ROM-gamma.jpg|250px|thumb|[[Obverse|Reverse]] and Obverse Sides of Narmer Palette, this facsimile on display at the [[Royal Ontario Museum]], in [[Toronto]], [[Canada]].]] |

| − | + | The origin of Egyptian hieroglyphs is uncertain, although it is clear that they constitute one of the oldest known [[writing system]]s in the world. Egyptian hieroglyphs may pre-date [[Sumer]]ian [[cuneiform]] writing, making them the oldest known writing system; or the two writing systems may have evolved simultaneously. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | One of the oldest and most famous examples of Egyptian hieroglyphs can be found on the [[Narmer Palette]], a [[shield]] shaped palette that dates to around 3200 B.C.E. The Narmer Palette has been described as "the first historical document in the world."<ref>Bob Brier, ''Daily Life of the Ancient Egyptians'' (Greenwood Press, 1999, ISBN 0313303134), 202.</ref> The palette was discovered in 1898 by [[archaeologist]]s [[James E. Quibell]] and [[Frederick W. Green]] in the ancient city of [[Nekhen]] (currently Hierakonpolis), believed to be the Pre-Dynastic capital of Upper Egypt. The palette is believed to be a gift offering from King [[Narmer]] to the god [[Amun]]. Narmer’s name is written in glyphs at the top on both the front and back of the palette.<ref>Francesca Jourdan, [http://www.ptahhotep.com/articles/Narmer_palette.html "The Narmer Palette,"] ''InScription, Journal of Ancient Egypt'' (7), 2000. Retrieved February 23, 2009.</ref> | ||

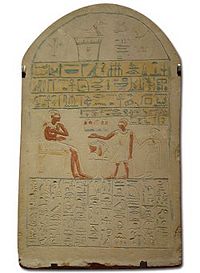

| + | [[Image:Egyptian funerary stela.jpg|thumb|200px|left|Hieroglyphs on an Egyptian funerary stela.]] | ||

| + | The Egyptians used hieroglyphs mainly for formal, religious inscriptions (hence their name, "the god’s words"). [[Hieratic]], or "priestly" script developed alongside hieroglyphs and was used extensively on religious degrees, manuscripts, and [[painting]]s. Hieratic script is essentially a simplified form of hieroglyphic writing that was much easier to write using [[ink]] and [[papyrus]]. Around 600 B.C.E., the [[Demotic (Egyptian)|demotic]] script replaced hieratic for everyday use. Though similar in form to hieratic script, the highly cursive demotic script has significant differences, and there is no longer the one-to-one correspondence with hieroglyphic signs that exists in the hieratic script.<ref>Lawrence Lo, [http://www.ancientscripts.com/egyptian.html “Egyptian,”] AncientScripts.com, 2007. Retrieved February 23, 2009.</ref> Demotic script did not replace hieroglyphic script, but rather existed alongside it; the priests continuing to use hieratic for religious writings while demotic was used for secular purposes. | ||

| + | Hieroglyphs continued to be after the [[Persia]]n invasion, as well as during the [[Macedonia]]n and [[Ptolemaic]] periods. The Greeks used their own [[Greek alphabet|alphabet]] for writing the Egyptian language, adding several glyphs from the demotic script for sounds not present in Greek; the result being the [[Coptic alphabet]]. Although the Egyptians were taught the [[Greek language]] and its alphabet under the rule of the Ptolemys, they did not abandon their hieroglyphic writing. It was not until the [[Ancient Rome|Roman]] invasion of 30 B.C.E. that use of hieroglyphs started to dramatically decrease: Roman rule was harsh, and the Egyptian people were subjected to heavy [[tax]]es and less autonomy than other Roman provinces. The final blow to hieroglyphs came in 391 C.E., when Emperor [[Theodosius I]] declared [[Christianity]] the only legitimate imperial religion, and ordered the closing of all [[pagan]] temples. By this time, hieroglyphs were used only in temples and on [[monument]]al [[architecture]].<ref>Jennifer Hill, [http://www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/hieroglyphs.html “Ancient Egypt Online.”] Retrieved February 23, 2009.</ref> The last known hieroglyphic inscription, carved on the gate of [[Hadrian]] at [[Philae]], is dated to 394 C.E. | ||

| − | + | Hieroglyphs survive today in two forms: Directly, through the half dozen demotic glyphs added to the Greek alphabet when writing Coptic; and indirectly, as the inspiration for the [[Proto-Sinaitic script]], discovered in [[Palestine]] and [[Sinai]] by [[William Flinders Petrie]] and dated to 1500 B.C.E. In [[Canaan]] this developed into the [[Proto-Canaanite alphabet]], believed to be ancestral to nearly all modern alphabets, having evolved into the [[Phoenician alphabet|Phoenician]], [[Hebrew alphabet|Hebrew]], and [[Greek alphabet]]s. | |

| − | + | ==Deciphering hieroglyphs== | |

| + | Those who conquered Egypt during the time when hieroglyphs and hieratic script were in common use did not learn them. Thus, although the Greeks developed the Coptic alphabet for writing the Egyptian language, they included only a few demotic glyphs. When the Egyptian religion, which was the last use of hieroglyphs, was replaced with [[Christianity]], all knowledge of hieroglyphs was lost and they came to be regarded as mysterious, [[symbol]]ic representations of sacred knowledge, even by those contemporary with Egyptians who still understood them. | ||

| − | + | ===Arabic studies=== | |

| + | Almost from its inception, the study of [[Egyptology]] was dominated by a Euro-centric view, and it was a widely accepted fact that French Egyptologist [[Jean Francois Champollion]] was the first to decipher hieroglyphic writing. However, work by Egyptologist [[Okasha El Daly]] uncovered a vast corpus of [[medieval]] Arabic writing that reveals that to Arabic scholars, such as [[Ibn Wahshiyya]], in the ninth and tenth centuries, hieroglyphs were not just symbolic but could represent sounds as well as ideas.<ref>Okasha El Daly, ''Egyptology: The Missing Millennium'' (London: University College London Press, 2005, ISBN 1844720632).</ref> In part, these manuscripts were scattered amongst private and public collections, and were either uncataloged or misclassified. Since Egyptologists erroneously believed Arabs did not study Egyptian culture, the significance of these manuscripts to Egyptology was overlooked for centuries.<ref>Science Daily, [http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2004/10/041007085716.htm “Hieroglyphics Cracked 1,000 Years Earlier Than Thought,”] October 7, 2004. Retrieved February 23, 2009.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ===Early Western attempts=== | |

| − | + | In early Western attempts to decipher hieroglyphs there was a prevailing belief in the [[symbol]]ic, rather than [[phonetic]] nature of hieroglyphic writing. Works like [[Horapollo]]’s ''Hieroglyphica,'' likely written during the fifth century, contained authoritative yet largely false explanations of a vast number of glyphs. Horapollo claimed to have interviewed one of the last remaining writers of hieroglyphs, and stated that each symbol represented an abstract concept, transcending language to record thoughts directly. This, of course, was untrue, but it set the stage for a widespread belief that the glyphs represented secret [[wisdom]] and [[knowledge]]. Imaginative books like [[Nicolas Caussin]]’s ''De Symbolica Aegyptiorum Sapientia'' (The Symbolic Wisdom of Egypt) (1618) further pushed the translation of the glyphs into the realm of the imagination.<ref>BBC, [http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A20725742 “Hieroglyphs.”] Retrieved February 23, 2009.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===The Rosetta Stone=== | |

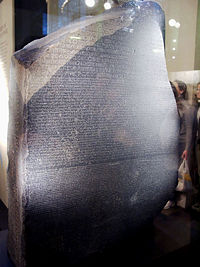

| + | [[Image:rosetta stone.jpg|thumb|200px|right|The [[Rosetta Stone]] in the [[British Museum]].]] | ||

| + | While [[Ancient Egypt]]ian culture fascinated Western scholars, the meaning of hieroglyphs remained an elusive mystery. For nearly fourteen hundred years, Western scholars were not even sure that hieroglyphs were a true [[writing system]]. If the glyphs were symbolic in nature, they might not represent actual, spoken [[language]]. Various scholars attempted to decipher the glyphs over the centuries, notably [[Johannes Goropius Becanus]] in the sixteenth century and [[Athanasius Kircher]] in the seventeenth; but all such attempts met with failure. The real breakthrough in decipherment began with the discovery of the [[Rosetta Stone]] by [[Napoleon]]'s troops in 1799. The Rosetta Stone contained three translations of the same text: One in Greek, one in demotic, and one in hieroglyphs. Not only were hieroglyphs a true writing system, but scholars now had a translation of the hieroglyphic text in an understood language: Greek. | ||

| − | + | The Rosetta Stone was discovered in the Egyptian city of Rosetta (present-day Rashid) in 1799, during Napoleon’s [[Napoleonic Campaign in Egypt|campaign in Egypt]]. While the French initially had possession of the stone, it eventually made its way into the hands of the English. Two scholars in particular worked to decipher the Stone’s mysteries: [[Thomas Young]] of [[Great Britain]], and French Egyptologist [[Jean Francois Champollion]]. In 1814, Young was the first to show that some of the glyphs on the stone wrote the sounds of a royal name, [[Ptolemy]]. Champollion, who is generally credited with the translation of the hieroglyphic text of the Rosetta Stone, was then able to determine the phonetic nature of hieroglyphs and fully decipher the text by the 1820s.<ref>British Museum, “The Rosetta Stone,” The British Museum.</ref> | |

== Writing system == | == Writing system == | ||

| − | + | Visually, hieroglyphs are all more or less figurative: They represent real or illusional elements, sometimes stylized and simplified, and generally recognizable in form. However, the same sign can, according to context, be interpreted in diverse ways: as a [[phonogram]], as a [[logogram]], or as an [[ideogram]]. Additionally, signs can be used as [[determinative]]s, where they serve to clarify the meaning of a certain word. | |

| − | |||

| − | Visually hieroglyphs are all more or less figurative: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ===Organization of glyphs=== | ||

| + | Hieroglyphs are most commonly written from right to left, but can also be written left to right, or top to bottom. The direction the glyphs should be read is indicated by the direction faced by asymmetrical glyphs. When [[human being|human]] and [[animal]] glyphs face to the right, the text should be read from right to left. Conversely, when the glyphs face left, the text should be read left to right. | ||

| − | + | Like other ancient writing systems, words are not separated by blanks or by [[punctuation]] marks. However, certain glyphs tend to commonly appear at the end of words, making it possible to readily distinguish where one word stops and another begins. | |

| + | ===Phonograms=== | ||

| − | + | Most hieroglyphic signs are [[phonetic]] in nature, where the meaning of the sign is read independent of its visual characteristics, much like the letters of modern [[alphabet]]s. Egyptian hieroglyphics did not incorporate vowels, and a single glyph can be either uniconsonantal, biconsonantal, or triconsonantal (representing one, two, or three consonants respectively). There are twenty-four uniconsonantal (or uniliteral) signs, which make up what is often called the “hieroglyphic alphabet.” It would have been possible to write all Egyptian words with just the uniconsonantal glyphs, but the Egyptians never did so and never simplified their complex writing into a true alphabet.<ref>Alan H. Gardiner, ''Egyptian Grammar'' (The Griffith Institute, 1973, ISBN 0900416351).</ref> | |

| − | + | ===Determinatives=== | |

| − | '' | + | Phonetically spelled words are often accompanied by additional glyphs that clarify the spelling. For example, the word ''nfr'', "beautiful, good, perfect," was written with a unique triliteral which was read as ''nfr,'' but was often followed by the unilaterals for “f” and “r,” in order to clarify the spelling. Even though the word then become “nfr+f+r,” it is read simply as “nfr.” |

| − | + | These type of determinatives, or phonetic complements, are generally placed after a word, but occasionally precede or frame the word on both sides. Ancient Egyptian scribes placed a great deal of importance on the aesthetic qualities as well as the meaning of the writing, and would sometimes add additional phonetic complements to take up space or make the writing more artistic. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Determinatives also serve to distinguish [[homophone]]s from one another, as well as glyphs that have more than one meaning. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Logograms=== | |

| − | + | In addition to a phonetic interpretation, most hieroglyphs can also be used as [[logogram]]s, where a single sign stands for the word. Logograms are accompanied by a silent vertical stroke that indicates the glyph should be read as a logogram. Logograms can also be accompanied by phonetic complements that clarify their meaning. | |

| − | + | *For example, the glyph for “r,” ''{{unicode|rˁ}}'', when accompanied by a vertical stroke, means “[[sun]]:” | |

| − | + | ||

| + | <hiero>ra:Z1</hiero> | ||

| + | *The phonetic glyph ''pr'' means "house" when accompanied by a vertical stroke: | ||

| + | <hiero>pr:Z1</hiero> | ||

| − | + | Other examples can be more indirect. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | *The logogram ''dšr'', means "[[flamingo]]:" | |

| + | <hiero>G27-Z1</hiero> | ||

| − | + | The corresponding phonogram, without the vertical stroke, means "red" because the bird is associated with this [[color]]: | |

| − | + | <hiero>G27</hiero> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Additional signs=== | ===Additional signs=== | ||

| − | + | In addition to phonetic, logographic, and determinative signs, Egyptian scribes also employed the use of other signs. An important example is the [[cartouche]]—an oblong enclosure with a horizontal line at one end—which indicated that the text enclosed is a royal name: | |

| − | + | {{Hiero/1cartouche|align=left|era=ok|name=[[Ptolemaic dynasty|Ptolemy]]|nomen=<hiero>p:t-wA-l:M-i-i-s</hiero>}} | |

| − | |||

| − | <hiero> | ||

| − | |||

| − | < | + | The glyphs in this cartouche are transliterated as: pt+o+lm+ii+s, where “ii” is translated as “y,” spelling out the name of the ruler [[Ptolemy]]. This cartouche was significant in the decipherment of the [[Rosetta Stone]]; the [[Greek]] ruler Ptolemy V was mentioned in the Greek text on the stone, and Champollion was able to use this correlation to decipher the names of Egyptian rulers [[Ramesses]] and [[Thutmose]], and thereby determine the phonetic and [[logograph]]ic natures of hieroglyphic script.<ref>History World, [http://history-world.org/hieroglyphics.htm “Ancient Egypt, Hieroglyphics.”] Retrieved February 23, 2009.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | + | There are a number of other signs, often [[grammar|grammatical]] in nature: Filling strokes, as their name implies, serve to fill up empty space at the end of a quadrant of text. To indicate two of a word, the sign is doubled; to indicate a plural, the sign is tripled. Some signs are also formed from a combination of several other signs, creating a new meaning. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Reading Hieroglyphs== |

| − | + | It is nearly impossible to know the true [[pronunciation]] of many ancient Egyptian words, particularly since there are no [[vowel]]s in hieroglyphic script. Modern pronunciation of ancient Egyptian has numerous problems. Because of the lack of vowels, Egyptologists developed conventions of inserting vowel sounds in order to make words pronounceable in discussion and lectures. The triconsonontal glyph “nfr” thereby became known as “nefer,” and so forth. | |

| − | + | Another problem is that the lack of standardized spelling—one or more variants existed for numerous words. Many apparent spelling errors may be more an issue of chronology than actual errors; spelling and standards varied over time, as they did in many other languages (including English). However, older spellings of words were often used alongside newer practices, confusing the issue. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Cataloging systems such as [[Gardiner's Sign List]], a list of common Egyptian hieroglyphs compiled by Sir [[Alan Gardiner]] and considered a standard reference, are now available to understand the context of texts, thus clarifying the presence of determinatives, ideograms, and other ambiguous signs in transliteration. There is also a standard system for the computer-encoding of transliterations of Egyptian hieroglyphic texts, known as the "[[Manuel de Codage]]." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Clues about the pronunciation of the late stages of the Egyptian language can found as Egyptians began to write exclusively with the [[Greek alphabet]]. Seven letters were borrowed from the [[demotic]] alphabet to represent sounds that did not exist in Greek. Because the Greek alphabet includes vowels, scholars have a good idea what the last stage of Egyptian language ([[Coptic]]) sounded like, and can make inferences about earlier pronunciations. Although Coptic has not been a spoken language since the seventeenth century, it has remained the language of the [[Coptic Church]], and learning this language aided Champollion in his decipherment of the [[Rosetta Stone]].<ref>Kelley L. Ross, [http://www.friesian.com/egypt.htm “The Pronunciation of Ancient Egyptian,”] ''The Proceedings of the Friesian School, Fourth Series,'' 2007. Retrieved February 23, 2009.</ref> | ||

| + | ==Gallery== | ||

| + | <Gallery> | ||

| + | Image:Border stela Senusret III Berlin.jpg|Border Stela of Senusret III. Middle Kingdom of Egypt, 12th dynasty, c. 1860 B.C.E. | ||

| + | Image:Dynasty 18 balustrade decorated with royal cartouches REM.JPG|Limestone balustrade decorated with royal cartouches from Amarna (Dynasty 18). | ||

| + | Image:Egypte louvre 232 pot.jpg|An amphora-type pot with 3 columns of hieroglyphs. | ||

| + | Image:Pyramid text Teti.jpg|Pyramid text in Teti pyramid in Saqqara, Egypt. | ||

| + | Image:Ägyptisches Museum Leipzig 094.jpg|Statue of Memi, left side; Giza, 5th dynasty. | ||

| + | Image:EgyptMuseumBerlin2007055.JPG|Kneeling statue, presenting a memorial stele. | ||

| + | Image:Scarab artifact Rameses II CdM Luynes881.jpg|Scarab with the cartouche of Rameses II: Pharaoh firing bow. | ||

| + | Image:Louvre 122007 27.jpg|Red granite sarcophagus of Ramses III. Goddess Nephthys seated on the Egyptian language hieroglyph for gold. | ||

| + | Image:Louvre 042005 06.jpg|Sphinx-lion of Thutmose III, laying on the Nine Bows (the foreign peoples in subjugation), and the Thutmosis cartouche on the sphinx's breast. | ||

| + | Image:HatshepsutSarcophagus-ReinscribedForHerFather MuseumOfFineArtsBoston.png|Sarcophagus originally intended for Hatshepsut, reinscribed for her father, Thutmose I. Made of painted quartzite, from the Valley of the Kings, Thebes. 18th dynasty, reign of Hatshepsut, circa 1473-1458 B.C.E. | ||

| + | Image:QuartziteBlockStatueOfSenenmut-BritishMuseum-August19-08.jpg|Quartzite block statue of Senenmut, from the time of the 18th dynasty, circa 1480 B.C.E. Originally from Thebes, at the Temple of Karnak. Inscriptions on the body emphasize his relationship with Thutmose III, while those on the base talk about Hatshepsut. | ||

| + | Image:La tombe de Horemheb (KV.57) (Vallée des Rois Thèbes ouest) -8.jpg|Egyptian hieroglyph text on a royal sarcophagus from the Valley of the Kings (KV.57), the tomb of Horemheb the last Pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty from 1319 B.C.E. to late 1292 B.C.E. | ||

| + | </Gallery> | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | * | + | *Adkins, Lesley, and Roy Adkins. ''The Keys of Egypt: The Obsession to Decipher Egyptian Hieroglyphs''. HarperCollins Publishers, 2000. ISBN 0060194391. |

| − | * | + | *Allen, James P. ''Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs''. Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0521774837. |

| − | * | + | *Collier, Mark, and Bill Manley. ''How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs: A Step-by-step Guide to Teach Yourself''. British Museum Press, 1998. ISBN 0714119105. |

| − | * | + | *El Daly, Okasha. ''Egyptology: The Missing Millennium''. London: University College London Press, 2005. ISBN 1844720632. |

| − | * | + | *Faulkner, Raymond O. ''Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian''. The Griffith Institute, 1962. ISBN 0900416327. |

| − | * | + | *Gardiner, Alan H. ''Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs''. The Griffith Institute, 1973 (original 1957). ISBN 0900416351. |

| − | * McDonald, Angela. ''Write Your Own Egyptian Hieroglyphs''. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007 | + | *Kamrin, Janice. ''Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs; A Practical Guide''. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2004. ISBN 081094961X. |

| − | + | *McDonald, Angela. ''Write Your Own Egyptian Hieroglyphs''. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007. ISBN 0520252357. | |

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved February 12, 2024. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | *[http://www.catchpenny.org/codage/ "Manuel de Codage"] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *[http://www. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Ancient Egypt topics}} | {{Ancient Egypt topics}} | ||

| − | |||

{{writing systems}} | {{writing systems}} | ||

{{Credits|Egyptian_hieroglyphs|255810462}} | {{Credits|Egyptian_hieroglyphs|255810462}} | ||

Latest revision as of 00:01, 13 February 2024

|

Egyptian hieroglyphs | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Type |

logography usable as an abjad | |

|

Spoken languages |

Egyptian language | |

|

Time period |

3200 B.C.E. – 400 C.E. | |

|

Parent systems |

(Proto-writing) | |

|

Child systems |

Hieratic, Demotic, Meroitic, Middle Bronze Age alphabets | |

|

ISO 15924 |

Egyp | |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Egyptian hieroglyphs are a formal writing system used by the ancient Egyptians, and are perhaps the most widely recognized form of hieroglyphic writing in the world. The term "hieroglyph" originally referred only to Egyptian hieroglyphs, but has now been expanded to include other hieroglyphic scripts, such as Cretan, Luwian, Mayan, and Mi'kmaq. The Egyptians used hieroglyphs mainly for formal, religious inscriptions (hence their name, "the god’s words"). Egyptian glyphs, like those of many other hieroglyphic scripts, often consist of recognizable objects such as the sun or a bird, and incorporate a combination of logographic and phonetic elements.

Egyptian hieroglyphs constitute one of the oldest known writing systems in the world. Developed from pictures that symbolized well known objects, they allowed those in authority to document religious teachings as well as edicts from the pharoah. In this form the hieroglyphs were generally inscribed in permanent materials such as stone, and thus numerous examples of stelae and inscriptions on tombs have been discovered by archaeologists while excavating sites of importance to the ancient Egyptian culture. Contemporaneously, the hieratic script was developed to allow easier writing using ink on papyrus and later the demotic script was developed for secular use. It is through the use of this script that Egyptian hieroglyphs could be deciphered, as the Rosetta stone contains inscriptions of the same text in these scripts and Greek. Thus, it is now possible to know much about ancient Egyptian culture from thousands of years past through their hieroglyphic writing. Given the significance of this culture in human history, such understanding is of great value.

Etymology

The word "hieroglyph" derives from the Greek words ἱερός (hierós): "Sacred" and γλύφειν (glúphein): "To carve" or "to write," as in the term "glyph." This was translated from the Egyptian phrase "the god’s words," a phrase derived from the Egyptian practice of using hieroglyphic writing predominantly for religious or sacred purposes.

The term "hieroglyphics," used as a noun, was once common but now denotes more informal usage. In academic circles, the term "hieroglyphs" has replaced "hieroglyphic" to refer to both the language as a whole and the individual characters that compose it. "Hieroglyphic" is still used as an adjective (as in a hieroglyphic writing system).

History and evolution

The origin of Egyptian hieroglyphs is uncertain, although it is clear that they constitute one of the oldest known writing systems in the world. Egyptian hieroglyphs may pre-date Sumerian cuneiform writing, making them the oldest known writing system; or the two writing systems may have evolved simultaneously.

One of the oldest and most famous examples of Egyptian hieroglyphs can be found on the Narmer Palette, a shield shaped palette that dates to around 3200 B.C.E. The Narmer Palette has been described as "the first historical document in the world."[1] The palette was discovered in 1898 by archaeologists James E. Quibell and Frederick W. Green in the ancient city of Nekhen (currently Hierakonpolis), believed to be the Pre-Dynastic capital of Upper Egypt. The palette is believed to be a gift offering from King Narmer to the god Amun. Narmer’s name is written in glyphs at the top on both the front and back of the palette.[2]

The Egyptians used hieroglyphs mainly for formal, religious inscriptions (hence their name, "the god’s words"). Hieratic, or "priestly" script developed alongside hieroglyphs and was used extensively on religious degrees, manuscripts, and paintings. Hieratic script is essentially a simplified form of hieroglyphic writing that was much easier to write using ink and papyrus. Around 600 B.C.E., the demotic script replaced hieratic for everyday use. Though similar in form to hieratic script, the highly cursive demotic script has significant differences, and there is no longer the one-to-one correspondence with hieroglyphic signs that exists in the hieratic script.[3] Demotic script did not replace hieroglyphic script, but rather existed alongside it; the priests continuing to use hieratic for religious writings while demotic was used for secular purposes.

Hieroglyphs continued to be after the Persian invasion, as well as during the Macedonian and Ptolemaic periods. The Greeks used their own alphabet for writing the Egyptian language, adding several glyphs from the demotic script for sounds not present in Greek; the result being the Coptic alphabet. Although the Egyptians were taught the Greek language and its alphabet under the rule of the Ptolemys, they did not abandon their hieroglyphic writing. It was not until the Roman invasion of 30 B.C.E. that use of hieroglyphs started to dramatically decrease: Roman rule was harsh, and the Egyptian people were subjected to heavy taxes and less autonomy than other Roman provinces. The final blow to hieroglyphs came in 391 C.E., when Emperor Theodosius I declared Christianity the only legitimate imperial religion, and ordered the closing of all pagan temples. By this time, hieroglyphs were used only in temples and on monumental architecture.[4] The last known hieroglyphic inscription, carved on the gate of Hadrian at Philae, is dated to 394 C.E.

Hieroglyphs survive today in two forms: Directly, through the half dozen demotic glyphs added to the Greek alphabet when writing Coptic; and indirectly, as the inspiration for the Proto-Sinaitic script, discovered in Palestine and Sinai by William Flinders Petrie and dated to 1500 B.C.E. In Canaan this developed into the Proto-Canaanite alphabet, believed to be ancestral to nearly all modern alphabets, having evolved into the Phoenician, Hebrew, and Greek alphabets.

Deciphering hieroglyphs

Those who conquered Egypt during the time when hieroglyphs and hieratic script were in common use did not learn them. Thus, although the Greeks developed the Coptic alphabet for writing the Egyptian language, they included only a few demotic glyphs. When the Egyptian religion, which was the last use of hieroglyphs, was replaced with Christianity, all knowledge of hieroglyphs was lost and they came to be regarded as mysterious, symbolic representations of sacred knowledge, even by those contemporary with Egyptians who still understood them.

Arabic studies

Almost from its inception, the study of Egyptology was dominated by a Euro-centric view, and it was a widely accepted fact that French Egyptologist Jean Francois Champollion was the first to decipher hieroglyphic writing. However, work by Egyptologist Okasha El Daly uncovered a vast corpus of medieval Arabic writing that reveals that to Arabic scholars, such as Ibn Wahshiyya, in the ninth and tenth centuries, hieroglyphs were not just symbolic but could represent sounds as well as ideas.[5] In part, these manuscripts were scattered amongst private and public collections, and were either uncataloged or misclassified. Since Egyptologists erroneously believed Arabs did not study Egyptian culture, the significance of these manuscripts to Egyptology was overlooked for centuries.[6]

Early Western attempts

In early Western attempts to decipher hieroglyphs there was a prevailing belief in the symbolic, rather than phonetic nature of hieroglyphic writing. Works like Horapollo’s Hieroglyphica, likely written during the fifth century, contained authoritative yet largely false explanations of a vast number of glyphs. Horapollo claimed to have interviewed one of the last remaining writers of hieroglyphs, and stated that each symbol represented an abstract concept, transcending language to record thoughts directly. This, of course, was untrue, but it set the stage for a widespread belief that the glyphs represented secret wisdom and knowledge. Imaginative books like Nicolas Caussin’s De Symbolica Aegyptiorum Sapientia (The Symbolic Wisdom of Egypt) (1618) further pushed the translation of the glyphs into the realm of the imagination.[7]

The Rosetta Stone

While Ancient Egyptian culture fascinated Western scholars, the meaning of hieroglyphs remained an elusive mystery. For nearly fourteen hundred years, Western scholars were not even sure that hieroglyphs were a true writing system. If the glyphs were symbolic in nature, they might not represent actual, spoken language. Various scholars attempted to decipher the glyphs over the centuries, notably Johannes Goropius Becanus in the sixteenth century and Athanasius Kircher in the seventeenth; but all such attempts met with failure. The real breakthrough in decipherment began with the discovery of the Rosetta Stone by Napoleon's troops in 1799. The Rosetta Stone contained three translations of the same text: One in Greek, one in demotic, and one in hieroglyphs. Not only were hieroglyphs a true writing system, but scholars now had a translation of the hieroglyphic text in an understood language: Greek.

The Rosetta Stone was discovered in the Egyptian city of Rosetta (present-day Rashid) in 1799, during Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt. While the French initially had possession of the stone, it eventually made its way into the hands of the English. Two scholars in particular worked to decipher the Stone’s mysteries: Thomas Young of Great Britain, and French Egyptologist Jean Francois Champollion. In 1814, Young was the first to show that some of the glyphs on the stone wrote the sounds of a royal name, Ptolemy. Champollion, who is generally credited with the translation of the hieroglyphic text of the Rosetta Stone, was then able to determine the phonetic nature of hieroglyphs and fully decipher the text by the 1820s.[8]

Writing system

Visually, hieroglyphs are all more or less figurative: They represent real or illusional elements, sometimes stylized and simplified, and generally recognizable in form. However, the same sign can, according to context, be interpreted in diverse ways: as a phonogram, as a logogram, or as an ideogram. Additionally, signs can be used as determinatives, where they serve to clarify the meaning of a certain word.

Organization of glyphs

Hieroglyphs are most commonly written from right to left, but can also be written left to right, or top to bottom. The direction the glyphs should be read is indicated by the direction faced by asymmetrical glyphs. When human and animal glyphs face to the right, the text should be read from right to left. Conversely, when the glyphs face left, the text should be read left to right.

Like other ancient writing systems, words are not separated by blanks or by punctuation marks. However, certain glyphs tend to commonly appear at the end of words, making it possible to readily distinguish where one word stops and another begins.

Phonograms

Most hieroglyphic signs are phonetic in nature, where the meaning of the sign is read independent of its visual characteristics, much like the letters of modern alphabets. Egyptian hieroglyphics did not incorporate vowels, and a single glyph can be either uniconsonantal, biconsonantal, or triconsonantal (representing one, two, or three consonants respectively). There are twenty-four uniconsonantal (or uniliteral) signs, which make up what is often called the “hieroglyphic alphabet.” It would have been possible to write all Egyptian words with just the uniconsonantal glyphs, but the Egyptians never did so and never simplified their complex writing into a true alphabet.[9]

Determinatives

Phonetically spelled words are often accompanied by additional glyphs that clarify the spelling. For example, the word nfr, "beautiful, good, perfect," was written with a unique triliteral which was read as nfr, but was often followed by the unilaterals for “f” and “r,” in order to clarify the spelling. Even though the word then become “nfr+f+r,” it is read simply as “nfr.”

These type of determinatives, or phonetic complements, are generally placed after a word, but occasionally precede or frame the word on both sides. Ancient Egyptian scribes placed a great deal of importance on the aesthetic qualities as well as the meaning of the writing, and would sometimes add additional phonetic complements to take up space or make the writing more artistic.

Determinatives also serve to distinguish homophones from one another, as well as glyphs that have more than one meaning.

Logograms

In addition to a phonetic interpretation, most hieroglyphs can also be used as logograms, where a single sign stands for the word. Logograms are accompanied by a silent vertical stroke that indicates the glyph should be read as a logogram. Logograms can also be accompanied by phonetic complements that clarify their meaning.

- For example, the glyph for “r,” rˁ, when accompanied by a vertical stroke, means “sun:”

| |

- The phonetic glyph pr means "house" when accompanied by a vertical stroke:

| |

Other examples can be more indirect.

- The logogram dšr, means "flamingo:"

| |

The corresponding phonogram, without the vertical stroke, means "red" because the bird is associated with this color:

| |

Additional signs

In addition to phonetic, logographic, and determinative signs, Egyptian scribes also employed the use of other signs. An important example is the cartouche—an oblong enclosure with a horizontal line at one end—which indicated that the text enclosed is a royal name:

| Ptolemy in hieroglyphs | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The glyphs in this cartouche are transliterated as: pt+o+lm+ii+s, where “ii” is translated as “y,” spelling out the name of the ruler Ptolemy. This cartouche was significant in the decipherment of the Rosetta Stone; the Greek ruler Ptolemy V was mentioned in the Greek text on the stone, and Champollion was able to use this correlation to decipher the names of Egyptian rulers Ramesses and Thutmose, and thereby determine the phonetic and logographic natures of hieroglyphic script.[10]

There are a number of other signs, often grammatical in nature: Filling strokes, as their name implies, serve to fill up empty space at the end of a quadrant of text. To indicate two of a word, the sign is doubled; to indicate a plural, the sign is tripled. Some signs are also formed from a combination of several other signs, creating a new meaning.

Reading Hieroglyphs

It is nearly impossible to know the true pronunciation of many ancient Egyptian words, particularly since there are no vowels in hieroglyphic script. Modern pronunciation of ancient Egyptian has numerous problems. Because of the lack of vowels, Egyptologists developed conventions of inserting vowel sounds in order to make words pronounceable in discussion and lectures. The triconsonontal glyph “nfr” thereby became known as “nefer,” and so forth.

Another problem is that the lack of standardized spelling—one or more variants existed for numerous words. Many apparent spelling errors may be more an issue of chronology than actual errors; spelling and standards varied over time, as they did in many other languages (including English). However, older spellings of words were often used alongside newer practices, confusing the issue.

Cataloging systems such as Gardiner's Sign List, a list of common Egyptian hieroglyphs compiled by Sir Alan Gardiner and considered a standard reference, are now available to understand the context of texts, thus clarifying the presence of determinatives, ideograms, and other ambiguous signs in transliteration. There is also a standard system for the computer-encoding of transliterations of Egyptian hieroglyphic texts, known as the "Manuel de Codage."

Clues about the pronunciation of the late stages of the Egyptian language can found as Egyptians began to write exclusively with the Greek alphabet. Seven letters were borrowed from the demotic alphabet to represent sounds that did not exist in Greek. Because the Greek alphabet includes vowels, scholars have a good idea what the last stage of Egyptian language (Coptic) sounded like, and can make inferences about earlier pronunciations. Although Coptic has not been a spoken language since the seventeenth century, it has remained the language of the Coptic Church, and learning this language aided Champollion in his decipherment of the Rosetta Stone.[11]

Gallery

Notes

- ↑ Bob Brier, Daily Life of the Ancient Egyptians (Greenwood Press, 1999, ISBN 0313303134), 202.

- ↑ Francesca Jourdan, "The Narmer Palette," InScription, Journal of Ancient Egypt (7), 2000. Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ↑ Lawrence Lo, “Egyptian,” AncientScripts.com, 2007. Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ↑ Jennifer Hill, “Ancient Egypt Online.” Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ↑ Okasha El Daly, Egyptology: The Missing Millennium (London: University College London Press, 2005, ISBN 1844720632).

- ↑ Science Daily, “Hieroglyphics Cracked 1,000 Years Earlier Than Thought,” October 7, 2004. Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ↑ BBC, “Hieroglyphs.” Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ↑ British Museum, “The Rosetta Stone,” The British Museum.

- ↑ Alan H. Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar (The Griffith Institute, 1973, ISBN 0900416351).

- ↑ History World, “Ancient Egypt, Hieroglyphics.” Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ↑ Kelley L. Ross, “The Pronunciation of Ancient Egyptian,” The Proceedings of the Friesian School, Fourth Series, 2007. Retrieved February 23, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adkins, Lesley, and Roy Adkins. The Keys of Egypt: The Obsession to Decipher Egyptian Hieroglyphs. HarperCollins Publishers, 2000. ISBN 0060194391.

- Allen, James P. Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0521774837.

- Collier, Mark, and Bill Manley. How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs: A Step-by-step Guide to Teach Yourself. British Museum Press, 1998. ISBN 0714119105.

- El Daly, Okasha. Egyptology: The Missing Millennium. London: University College London Press, 2005. ISBN 1844720632.

- Faulkner, Raymond O. Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian. The Griffith Institute, 1962. ISBN 0900416327.

- Gardiner, Alan H. Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs. The Griffith Institute, 1973 (original 1957). ISBN 0900416351.

- Kamrin, Janice. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs; A Practical Guide. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2004. ISBN 081094961X.

- McDonald, Angela. Write Your Own Egyptian Hieroglyphs. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007. ISBN 0520252357.

External links

All links retrieved February 12, 2024.

| |||||||

| |||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.