Counterculture

Counterculture is a term used to describe a cultural group whose values and norms of behavior run counter to those of the social mainstream of the day, the cultural equivalent of political opposition. Although distinct countercultural undercurrents exist in all societies, here the term counterculture refers to a more significant, visible phenomenon that reaches critical mass and persists for a period of time. A counterculture movement thus expresses the ethos, aspirations and dreams of a specific population during a certain period of time — a social manifestation of zeitgeist.

Alternative Definitions

In contemporary times, counterculture came to prominence in the news media as it was used to refer to the youth rebellion that swept North America, Western Europe, Australia and New Zealand during the 1960s and early 1970s. Earlier countercultural milieux in 19th century Europe included the traditions of Romanticism, Bohemianism and of the Dandy. Another important movement existed in a more fragmentary form in the 1950s, both in Europe and the US, in the form of the Beat generation (Beatniks), who typically sported beards, wore roll-neck sweaters, read the novels of Albert Camus and listened to Jazz music.

Counterculture is generally used to describe a theological, cultural, attitudinal or material position that does not conform to accepted societal norms. Yet, counterculture movements are often co-opted to spearhead commercial campaigns. Thus once taboo ideas (men wearing a woman's color — pink, for example) sometimes become popular trends.

Counterculture of the 1960s

Though it also developed in the United Kingdom, the counterculture of the 1960s began in the United States as a reaction against the conservative social norms of the 1950s, the political conservatism (and social repression) of the Cold War period, and the US government's extensive military intervention in Vietnam. [1] [2]

As the 1960s progressed, widespread tensions developed in American society that tended to flow along generational lines regarding the war in Vietnam, race relations, sexual mores, women's rights, traditional modes of authority, experimentation with psychedelic drugs and a predominantly materialist interpretation of the American dream.

New cultural forms emerged, including the pop music of English band the Beatles, which rapidly evolved to shape and reflect the youth culture's emphasis on change and experimentation. This was accelerated after 1964, when the Beatles were introduced to cannabis in a New York hotel room by Bob Dylan, another youth culture icon.

Social anthropologist Jentri Anders, based in California, has observed that a number of freedoms were endorsed within a countercultural community which she lived in and studied: "freedom to explore one’s potential, freedom to create one’s Self, freedom of personal expression, freedom from scheduling, freedom from rigidly defined roles and hierarchical statuses…" Additionally, Anders believed these people wished to modify childrens' education so that it didn't discourage "aesthetic sense, love of nature, passion for music, desire for reflection, or strongly marked independence…"

Civil Rights Movement

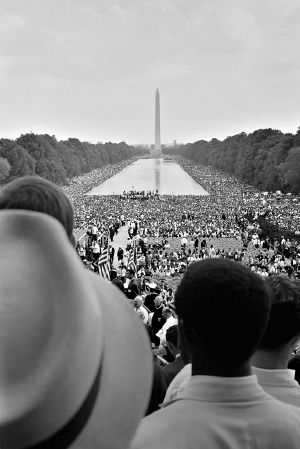

The African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968) was a biblically based movement that had significant social and political consequences for the United States. Black clergymen such as the Reverends Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph Abernathy, Joseph Lowery, Wyatt T. Walker, Fred Shuttlesworth, and numerous others relied on religious faith strategically applied to solve America's obstinate racial problems. Black, Christian leaders and their white allies joined together to challenge the immoral system of racial segregation. The Civil Rights Movement of 1955-1968 sought to address and rectify the generations-old injustices of racism by employing the method of nonviolent resistance which they believed to be modeled after the life and sacrifice of Jesus of Nazareth. The founding fathers of the United States had written of humanity's inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, but many did not believe this should apply to black slaves or women. The African-American Civil Rights movement put up a decade of struggle long after slavery had ended and after other milestones in the fight to overcome discriminatory, segregationist practices. Racism obstructs America's desire to be a land of human equality. The struggle for equal rights was also a struggle for the soul of the nation.

Free Speech Movement

In one view, the 1960s counterculture largely originated on college campuses. The 1964 Free Speech Movement at the University of California, Berkeley, which had its roots in the Civil Rights Movement of the American South, was one early example. At Berkeley a socially privileged group of students began to identify themselves as having interests as a class that were at odds with the interests and practices of the University and its corporate sponsors. However, other rebellious young people who had never been college students also contributed to counterculture development. The beatnik café and bar scene was a tributary stream.

New Left

The New Left is a term used in different countries to describe left-wing movements that occurred in the 1960s and 1970s. They differed from earlier leftist movements that had been more oriented towards labour activism, and instead adopted a broader definition of political activism commonly called social activism. The U.S. "New Left" is associated with college campus mass protest movements and radical leftists movements. The British "New Left" was an intellectually driven movement which attempted to correct the perceived errors of "Old Left" parties in the post-WWII period. The movements began to wind down in the 1970s, when activists either committed themselves to party projects, developed social justice organizations, moved into identity politics or alternative lifestyles or became politically inactive.

Antiwar Movement

Opposition to the Vietnam War began in 1964 on United states college campuses. Student activism was reinforced by the baby boomers, growing to include many Americans. Exemptions and deferments for the middle and upper classes resulted in the induction of a disproportionate number of poor, working-class, and minority registrants. By 1967, a majority of Americans opposed the war.

LSD

Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters helped shape the developing character of the 1960s counterculture when they embarked on a cross-country voyage during the summer of 1964 in a psychedelic school bus named "Furthur." Beginning in 1959, Kesey had volunteered as a research subject for medical trials financed by the CIA's MK ULTRA project. These trials tested the effects of LSD, psilocybin, mescaline, and other psychedelic drugs. After the medical trials, Kesey continued experimenting on his own, and involved many close friends; collectively they became known as "The Merry Pranksters." The Pranksters visited Harvard LSD proponent Timothy Leary at his Millbrook, New York retreat, and experimentation with LSD and other psychedelic drugs, primarily as a means for internal reflection and personal growth, became a constant during the Prankster trip. The Pranksters created a direct link between the 1950s Beat Generation and the 1960s psychedelic scene; the bus was driven by Beat icon Neal Cassady, Beat poet Allen Ginsberg was onboard for a time, and they dropped in on Cassady's friend, Beat author Jack Kerouac—though Kerouac declined participation in the Prankster scene. After the Pranksters returned to California, they popularized the use of LSD at so-called "Acid Tests," which initially were held at Kesey's home in La Honda, California, and then at many other West Coast venues. Experimentation with LSD and other psychedelic drugs became a major component of 1960s counterculture, influencing philosophy, art, music and styles of dress.

Black Power Movement

Black Power was a political movement, most prominent in the late 1960s and early 1970s, that strove to express a new racial consciousness among blacks in the United States. More generally, the term refers to a conscious choice on the part of blacks to nurture and promote their collective interests, advance their own values, and secure their own well-being and some measure of autonomy, rather than permit others to shape their futures and agendas. The first person to use the term Black Power in its political context was Robert F. Williams, a writer and publisher of the 1950s and '60s. Mukasa Dada (then known as Willie Ricks), an organizer and spokesperson for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), won the support of thousands of working-class blacks when he shouted "black power" at a time when the focus on racial integration, originally seen by some blacks as a strategic choice, had become an end in itself in more moderate circles. It is also used by many racists in exactly the same way as white power can be used to advance one's people or oppress another.

The focus of black power advocates was not integration or any other single strategy. Rather, it was improving the status of black people.

Hippies

In 1967 Scott McKenzie's rendition of the song "San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)" brought as many as 100,000 young people from all over the world to celebrate San Francisco's "Summer of Love." While the song had originally been written by John Phillips of The Mamas & The Papas to promote the June, 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, it became an instant hit worldwide (#4 in the United States, #1 in Europe) and quickly transcended its original purpose. San Francisco's Flower Children, also called "hippies" by local newspaper columnist Herb Caen, adopted new styles of dress, experimented with psychedelic drugs, lived communally and developed a vibrant music scene. When people returned home from "The Summer of Love" these styles and behaviors spread quickly from San Francisco and Berkeley to all major U.S. cities and European capitals. A counterculture movement gained momentum in which the younger generation began to define itself as a class that aimed to create a new kind of society. Some hippies formed communes to live as far outside of the established system as possible. This aspect of the counterculture rejected active political engagement with the mainstream and, following the dictate of Timothy Leary to "turn on, tune in, and drop out", hoped to change society by dropping out of it. Looking back on his own life (as a Harvard professor) prior to 1960, Leary interpreted it to have been that of "an anonymous institutional employee who drove to work each morning in a long line of commuter cars and drove home each night and drank martinis .... like several million middle-class, liberal, intellectual robots."

The hippie ethic posed a considerable impediment to the success of alternative movements growing within the counterculture. At the extremes, "doing one's own thing" could lead to rejection of values imposed from without and adamant avoidance of other people's expectations. As a result, the individual tends to be isolated, which may or may not be much of a problem for that individual – but it does threaten collaborative actions or accomplishments.

As members of the hippie movement grew older and moderated their lives and their views, and especially after all US involvement in the Vietnam War ground to a halt in the mid 1970s, the counterculture was largely absorbed by the mainstream, leaving a lasting impact on philosophy, morality, music, art, lifestyle and fashion.

Sexual revolution

The sexual revolution refers to a change in sexual morality and sexual behavior throughout the Western world. In general use, the term refers to a later trend of equalizing sexual behavior which occurred primarily during the 1960s, although the term has been used at least since the late 1920s.

Beginning in San Francisco in the mid 1960s, a new culture of "free love" arose, with tens of thousands of young people becoming hippies and preaching the power of love and the beauty of sex as a natural part of ordinary life. By the start of the 1970s it was acceptable for colleges to allow co-educational housing where male and female students mingled freely. This aspect of the counterculture continues to impact modern society.

In Europe

The counterculture movement took hold in Western Europe, with London, Amsterdam, Paris, Berlin and Rome rivaling San Francisco and New York as counterculture centers. One manifestation of this was the general strike that took place in Paris in May 1968, which nearly toppled the French government.

In Central Europe, young people adopted the song "San Francisco" as an anthem for freedom, and it was widely played during Czechoslovakia's 1968 "Prague Spring," a premature attempt to break away from Soviet repression.

As this newly emergent youth class began to criticize the established social order, new theories about cultural and personal identity began to spread, and traditional non-Western ideas – particularly with regard to religion, social organization and spiritual enlightenment – were more frequently embraced.

Feminism

Second Wave Feminism is generally identified with a period beginning in the early nineteen sixties and extending through the late nineteen eighties. Whereas first-wave feminism focused largely on de jure (officially mandated) inequalities, second wave feminism saw de jure and de facto (unofficial) inequalities as inextricably linked issues that had to be addressed in tandem.

The movement encouraged women to understand aspects of their own personal lives as deeply politicized, and reflective of a sexist structure of power. If first-wave feminism focused upon absolute rights such as suffrage, second-wave feminism was largely concerned with other issues of equality, such as the end to discrimination and oppression.

The role of women as full-time homemakers in industrial society was challenged in 1963, when American feminist Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique, giving momentum to the women's movement and influencing the second wave of feminism.

Alternative media

Underground newspapers sprang up in most cities and college towns, serving to define and communicate the range of phenomena that defined the counterculture: radical political opposition to "The Establishment," colorful experimental (and often explicitly drug-influenced) approaches to art, music and cinema, and uninhibited indulgence in sex and drugs as a symbol of freedom.

Music

During the early 1960s, Britain's new generation of blues rock gained popularity in its homeland and cult fame in the United States. Folk singers like Peter, Paul & Mary ("Puff the Magic Dragon") and Bob Dylan (The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan) influenced the British groups, and popular music became more closely aligned with the counterculture.

An international sound developed that moved towards an electric, psychedelic version of rock. In 1962 (see 1962 in music), The Beatles (Please Please Me) emerged from England and popularized British rock, while The Beach Boys' success brought harmony-laden surf music to the forefront of the American scene. With country and soul musicians unable to maintain their hipness, both faded from mass consciousness.

The Beatles went on to become the most prominent commercial exponents of the "psychedelic revolution" that occurred during the late 1960s, with few Americans able to challenge them—exceptions included The Mamas & the Papas ("California Dreaming") and Jimi Hendrix (Are You Experienced?). The most hard-edged psychedelic American bands, like the Jefferson Airplane (Surrealistic Pillow) and The Grateful Dead (American Beauty), achieved limited commercial success. As the first jam band, The Grateful Dead might also be considered the first cult act. Popular music underwent a sea change, and psychedelic rock came to dominate the music scene for both black and white audiences.

As the psychedelic revolution progressed, lyrics grew more complex and long playing albums enabled artists to make more in-depth statements than could be made in a single song. Even rules governing single songs were stretched—singles lasting longer than three minutes emerged for the first time (Bob Dylan's "Like a Rolling Stone" was the first of these).

Though not unheard of before the 1960s, the idea that popular music could and should lead social change came into its own during this period. Most existing musical styles were influenced, and new musical genres came into being, including heavy metal, punk rock, electronic music and hip hop.

Environmentalism

Environmentalism is a concern for the preservation, restoration, or improvement of the natural environment, such as the conservation of natural resources, prevention of pollution, and certain land use actions. Counterculture environmentalists were quick to grasp the early analyses and the import of the Hubbert "peak oil" prediction. More broadly they saw that the dilemmas of energy derivation would have implications for geo-politics, lifestyle, environment, and other dimensions of modern life.

Technology

In his 1986 essay From Satori to Silicon Valley, cultural historian Theodore Roszak pointed out that Apple Computer emerged from within the West Coast counterculture. Roszak outlines the Apple computer's development, and the evolution of 'the two Steves' (Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs, the Apple's developers) into businessmen. Like them, many early computing and networking pioneers – after discovering LSD and roaming the campuses of UC Berkeley, Stanford, and MIT in the late 60s and early 70s – would emerge from this caste of social "misfits" to shape the modern world.

The counterculture had representatives in the sciences, the trades, business, and law. Many counterculture participants were stable, dedicated, and persistent. Much was done in the area of the human interface with the natural environment (in connection with science, technologies, community planning, parks, and other spheres). While ad hoc action groups sprang up frequently, usually fading away just as quickly, some established themselves as ongoing non-governmental organizations (NGOs) dedicated to working toward particular goals. The counterculture gave rise to many lasting NGOs.

Legacy

The legacy of the 1960s Counterculture is still actively contested in debates that are sometimes framed, in the U.S., in terms of a "culture war." Jay Walljasper, a commentator and the editor of Utne Reader — though not himself from the so-called '60s Generation, and having grown up in American-Heartland farming country — has written, "From the great gyrations of the counterculture would come a movement dedicated to the greening of America. While many once-ardent advocates of radical ideas now live in the suburbs and vote Republican, others have held fast to the dream of creating a new kind of American society and they've been joined by fresh streams of younger idealists."

Examples of Counterculture

Sixties and seventies counterculture

Though it also developed in the United Kingdom, the counterculture of the 1960s began in the United States as a reaction against the conservative social norms of the 1950s, the political conservatism (and social repression) of the Cold War period, and the US government's extensive military intervention in Vietnam. [3] [4]

Tensions developed along generational lines during the sixties regarding experimentation with drugs, race relations, sexual mores and women's rights. New cultural forms emerged, including the pop music of Bob Dylan, the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane, and Bob Marley which rapidly evolved to shape and reflect the youth culture's emphasis on change and experimentation.

Russian/Soviet counterculture

Although not exactly equivalent to the English definition, the term "Контркультура" (Kontrkul'tura, "Counterculture") found a constant use in Russian to define a cultural movement that promotes acting outside usual conventions of Russian culture - use of explicit language, graphical description of sex, violence and illicit activities and uncopyrighted use of "safe" characters involved in everything mentioned.

During the early 70's, Russian culture was forced into quite a rigid framework of constant optimistic approach to everything. Even mild topics, such as breaking marriage and alcohol abuse, tended to be viewed as taboo by the media. In response, Russian society grew weary of the gap between real life and the creative world. Thus, the folklore and underground culture tended to be considered forbidden fruit. On the other hand, the general satisfaction with the quality of the existing works promoted parody, often within existing settings. For example, the Russian anecdotal joke tradition turned the settings of War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy into a grotesque world of sexual excess. Another well-known example is a black humor that dealt exclusively with funny deaths and/or other mishaps of small innocent children.

In the mid-80s, the Glasnost policy allowed the production of not-so-optimistic creative works. As a consequence, Russian cinema during the late 80s to the early 90s was dominated by crime-packed action movies with explicit (but not necessarily graphic) scenes of ruthless violence and social dramas on drug abuse, prostitution and failing relations. Although Russian movies of the time would be rated R in the USA due to violence, the use of explicit language was much milder than in American cinema.

Russian counterculture as we know it emerged in the late 90s with the increased popularity of the internet. Several web sites appeared that posted user-written short stories that dealt with sex, drugs and violence. Since stories were actually posted by editors, it's pretty clear what the characteristics of Russian counterculture were. The following features are considered most popular topics for the works:

- Wide use of explicit language

- Deliberately bad spelling

- Drug theme - descriptions of drug use and consequences of substance abuse - at times quite gruesome

- Alcohol use - positive

- Sex and violence - nothing is a taboo. In general, violence is rarely advocated, while sex is considered to be a good thing.

- Parody - media advertising, classic movies, pop culture and children's books are considered to be fair game.

- Nonconformism to daily routine and set nature of things

- Politically incorrect topics - mostly racism, xenophobia and homophobia

Media counterculture

While Phil Donahue pioneered the tabloid talk show genre in the 1970s, the warmth, intimacy and personal confession Oprah Winfrey brought to the format in 1986 both popularized and revolutionized it. , Yale sociology professor Joshua Gamson credits the tabloid talk show genre with providing much needed high impact media visibility for gays, bisexuals, transsexuals, and transgender people and doing more to make gays socially acceptable than any other development of the 20th century.[5] With the invention and propagation of tabloid talk shows such as Jerry Springer, Jenny Jones, Oprah, and Geraldo, people outside the sexual mainstream now appear in living rooms across America almost every day of the week. Sociologist Vicki Abt feared that tabloid talk shows were redefining social norms. In her book Coming After Oprah: Cultural Fallout in the Age of the TV talk show, Abt warned that the media revolution that followed Oprah's success was blurring the lines between normal and deviant behavior.[6]

One of Winfrey's most taboo-breaking shows occurred in the 1980s where for the entire hour, members of the studio audience stood up one by one, gave their names and announced that they were gay. Also in the 1980s Winfrey took her show to West Virginia to confront a town gripped by AIDS paranoia because a gay man living in the town had HIV. Winfrey interviewed the man, who had become a social outcast, and the town's mayor, who had drained a public pool where the man had gone swimming, and debated the town's hostile residents.

Following the success of tabloid talk shows, early 21st-century gays were coming out of the closet younger and younger, gay suicide rates had dropped, and gays were embraced on mainstream shows such as Queer as Folk, Will & Grace and Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, and films such as Brokeback Mountain.

Winfrey's intimate, therapeutic hosting style and the tabloid talk show genre she popularized has been credited or blamed for leading the media counterculture of the 1980s and 1990s, which broke 20th century taboos, led to America's self-help obsession, and created a confession culture. The Wall Street Journal coined the term Oprahfication, which means public confession as a form of therapy.[7]

Lesbian, gay, bisexual & transgender counterculture

The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender community (commonly abbreviated as the “LGBT” community) fits the definition a countercultural movement as "a cultural group whose values and norms of behavior run counter to those of the social mainstream of the day". Aside from breaking away from the traditional accepted sexual mores of American / western culture, it has weathered continual, sometimes intense opposition from the more conservative elements of society.

At the outset of the 20th century, homosexual acts were punishable offenses. The prevailing public attitude was that homosexuality was a moral failing that should be punished, as exemplified by Oscar Wilde’s 1895 trial and imprisonment for "gross indecency." But even then, there were dissenting views. Sigmund Freud publicly expressed his opinion that homosexuality was a perfectly normal condition for some people. According to Charles Kaiser’s “the Gay Metropolis”, there were already semi-public gay-themed gatherings by the mid-1930s (such as the annual drag balls held during the Harlem Renaissance). There were also many bars & bath-houses that catered to gay clientele and adopted warning procedures (similar to those used by prohibition-era speakeasies) to warn customers of police raids. But homosexuality was typically subsumed into bohemian culture, and was not a significant movement in itself.[8]

A genuine gay culture began to take root, albeit very discretely, with its own styles, attitudes and behaviors. And numerous industries began catering to this growing demographic group. For example, publishing houses cranked out pulp novels like “the Well of Loneliness” or “the Velvet Underground” that were targeted directly at gay people. By the early 1960s, openly gay political organizations such as the Mattachine Society were formally protesting abusive treatment toward gay people, challenging the entrenched idea that homosexuality was an aberrant condition, and calling for the decriminalization of homosexuality. Despite very limited sympathy, American society began at least to acknowledge the existence of a sizeable population of gays. The film “The Boys in the Band”, for example, featured negative portrayals of gay men, but at least recognized that they did in fact fraternize with each other (as opposed to being isolated, solitary predators who ‘victimized’ straight men).

A watershed event was the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York City. Following this event, gays and lesbians began adopting the militant street protest tactics used by anti-war and black power radicals to confront anti-gay ideology. Perhaps the zenith of this period was the 1973 decision by the American Psychiatric Association to remove homosexuality from the official list of mental disorders. Although gay radicals did use pressure tactics to force the decision, Kaiser notes that this had been an issue of some debate for many years in the psychiatric community, and that one of the chief obstacles to normalizing homosexuality was that therapists were getting rich offering dubious, unproven "cures".

The AIDS epidemic was a massive, unexpected blow to the movement. Many gays feared (and many fundamentalists hoped) that the disease would permanently drive gay life underground. But even AIDS had ironic, positive consequences. Many of the early victims of the disease had been openly gay only within the confines of insular gay ghettos (like NYC’s Greenwich Village and San Francisco’s Castro); they remained closeted in their professional lives and to their families. Many straights who thought they didn't know any gay people were confronted with friends, siblings and loved ones who were dying of ‘the gay plague.’ Gay people were increasingly seen not only as victims of a disease, but as victims of ostracism and hatred. Most importantly, the disease became a rallying point for a previously complacent gay community. Gay people once again became political and fought not only for a medical response to the plague, but also for wider acceptance of homosexuality in mainstream America. Ultimately, coming out in all aspects of one's life became an important step for many gay people.

The word "queer" had once been used as a derogatory term. During the 1980's gay people reclaimed the word as a defiant, pro-gay term. Its use became a broad declaration that gay men, lesbians, bisexuals and transgendered people would no longer 'apologize' for themselves, or try to placate homophobic elements.

In 2003, the United States Supreme Court officially decriminalized all sodomy laws. Virtually every large city and community in America has its own network of bars, gay-oriented businesses and community centers. Annual gay pride events take place throughout the country and the world. Many of the current debates concerning gay people (such as same-sex marriage and parenting) would have been unthinkable even 20 years ago. As of 2007, the gay community is focusing on marital rights, but sufficient numbers of Americans oppose gay marriage to the point that 27 state constitutional amendments banning gay marriage have been passed. This indicates that despite the wider acceptance and tolerance of gay life, it is still viewed by large segments of American society as divergent.

Conservative counterculture

In the early 2000s many political writers have coined a new term, "Conservative Counterculture," which describes a growing youth movement in both the Catholic and Evangelical churches in the United States.[9] This is a group of American teens and young people who no longer see themselves as part of the "MTV" establishment and who reject pre-marital sex, illegal drugs, and alcohol. This Conservative Counterculture can be seen as a backlash against the liberal hippie generation of the 1960s, in which sex and drugs were popularized and traditional relationships frowned upon.

Counterculture Today

Currently there is no "definitive" counterculture, however several social scenes are emerging as a counterculture. In recent years such groups as the Punks, Bohemians, and Indies have questioned how the United States conducts the "War on Terror," especially in Iraq. These groups also embrace the ideologies espoused in Communism, Anarchism, Anti-War, and Socialism opposing the more popular Conservative and Liberal political views. These groups also oppose the popular use of technology and embrace Art and more "Independent" views on products and music. They are also more accepting of other races, religions, and sexual orientations. Most of the emerging counterculture groups relate their ideas and views to those of the 1960s counterculture. Such "forgotten" drugs as LSD and heroin are becoming more popular, fueling fear of a new "Drug Epidemic."

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Hirsch, E.D. (1993). The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-65597-8. p 419. "Members of a cultural protest that began in the U.S. in the 1960's and affected Europe before fading in the 1970s...fundamentally a cultural rather than a political protest."

- ↑ "Rockin' At the Red Dog: The Dawn of Psychedelic Rock," Mary Works Covington, 2005.

- ↑ Eric Donald Hirsch.The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-65597-8. (1993) p 419. "Members of a cultural protest that began in the U.S. in the 1960's and affected Europe before fading in the 1970s...fundamentally a cultural rather than a political protest."

- ↑ "Rockin' At the Red Dog: The Dawn of Psychedelic Rock," Mary Works Covington, 2005.

- ↑ Freaks Talk Back University of Chicago Press. Retrieved February 12, 2007.

- ↑ Abt, Vicki. How TV Talkshows Deconstruct Society Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved February 12, 2007.

- ↑ Bathos and Credibility Wall Street Journal (subscription required). Retrieved February 12, 2007.

- ↑ The Gay Metropolis: 1940-1996 Findarticles.com. Retrieved February 12, 2007.

- ↑ Dreher, Rod. Crunchy Cons: The New Conservative Counterculture and Its Return to Roots. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 1400050650

Bibliography

- Ken Goffman (2004) Counterculture through the ages Villard Books ISBN 0-375-50758-2

- George McKay (1996) Senseless Acts of Beauty: Cultures of Resistance since the Sixties. London Verso. ISBN 1-85984-028-0.

- Elizabeth Nelson (1989) The British Counterculture 1966-73: A Study of the Underground Press. London: Macmillan.

- Theodor Roszak (1970) The Making of a Counter Culture. University of California Press. ISBN 0520201221

External links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.