Berber

| Berbers |

|---|

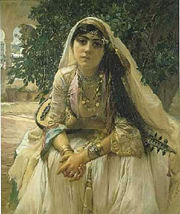

| 200px |

| Total population |

| c. 23 million |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Morocco: 19,000,000 Algeria: |

| Languages |

| Berber (Tamazight) |

| Religions |

| Islam (overwhelming majority), atheism, Christianity, Judaism, Others |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Afro-Asiatic Semitic |

The Berbers (also called Amazigh people or Imazighen, "free men", singular Amazigh) are an ethnic group indigenous to Northwest Africa, speaking the Berber languages of the Afroasiatic family. In actuality, Berber is a generic name given to numerous heterogeneous ethnic groups by the Romans, that share similar cultural, political, and economic practices. It is not a term originated by the group itself, and indeed the word may have been derived from the Greek 'βάρβαρος', the forerunner of the English word 'barbarian'. The Romans followed the Greek custom of designating speakers of unintelligible languages as "barbarians".

While Berbers are stereotyped as nomads, and indeed some tribes are, the majority are typically farmers. It's difficult to estimate the number of Berbers in the world today, because many don't consider themselves Berber. However the Berber language is spoken by an estimated 14 to 25 million people.

The name Berbers refers to the descendents of the pre-Arab popuilations of North Africa from teh Egyptian frontier to teh atlantic adn fro the Mediterranean coast to the Niger. The term comes fro the derogatory Greek word fo r non-Greek and was taken into both Latin and Arabic, yielding the English term Barbarian. [1]

Origin

There is no complete certitude about the origin of the Berbers; however, various disciplines shed light on the matter.

Genetic evidence

While population genetics is a young science still full of controversy, in general the genetic evidence appears to indicate that most northwest Africans (whether they consider themselves Berber or Arab) are predominantly of Berber origin, and that populations ancestral to the Berbers have been in the area since the Upper Paleolithic era. The genetically predominant ancestors of the Berbers appear to have come from East Africa, the Middle East, or both - but the details of this remain unclear. However, significant proportions of both the Berber and Arabized Berber gene pools derive from more recent human migration of various Italic, Semitic, Germanic, and sub-Saharan African peoples, all of whom have left their genetic footprints in the region.

Archaeological

The Neolithic Capsian culture appeared in North Africa around 9,500 B.C.E. and lasted until possibly 2700 B.C.E. Linguists and population geneticists alike have identified this culture as a probable period for the spread of an Afro-Asiatic language (ancestral to the modern Berber languages) to the area. The origins of the Capsian culture, however, are archeologically unclear. Some have regarded this culture's population as simply a continuation of the earlier Mesolithic Ibero-Maurusian culture, which appeared around ~22,000 B.C.E., while others argue for a population change; the former view seems to be supported by dental evidence. [1]

History

The Berbers have lived in North Africa between western Egypt and the Atlantic Ocean for as far back as records of the area go. The earliest inhabitants of the region are found on the rock art across the Sahara. References to them also occur frequently in ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman sources. Berber groups are first mentioned in writing by the ancient Egyptians during the Predynastic Period, and during the New Kingdom the Egyptians later fought against the Meshwesh and Lebu (Libyans) tribes on their western borders. Many Egyptologists think that from about 945 B.C.E. the Egyptians were ruled by Meshwesh immigrants who founded the Twenty-second Dynasty under Shoshenq I, beginning a long period of Berber rule in Egypt, although others posit different origins for these dynasties, including Nubian ones. They long remained the main population of the Western Desert - the Byzantine chroniclers often complained of the Mazikes (Amazigh) raiding outlying monasteries there.

For many centuries the Berbers inhabited the coast of North Africa from Egypt to the Atlantic Ocean. Over time, the coastal regions of North Africa saw a long parade of invaders and colonists including Saharans, Phoenicians (who founded Carthage), Greeks (mainly in Libya), Romans, Vandals and Alans, Byzantines, Arabs, Ottomans, and the French and Spanish. Most if not all of these invaders have left some imprint upon the modern Berbers as have slaves brought from throughout Europe (some estimates place the number of Europeans brought to North Africa during the Ottoman period as high as 1.25 million)[2]. Interactions with neighboring Sudanic empires, sub-Saharan Africans, and nomads from East Africa also left vast impressions upon the Berber peoples.

In historical times, the Berbers expanded south into the Sahara (displacing earlier populations such as the Azer and Bafour), and have in turn been mainly culturally assimilated in much of North Africa by Arabs, particularly following the incursion of the Banu Hilal in the 11th century.

The areas of North Africa which retained the Berber language and traditions have, in general, been those least exposed to foreign rule—in particular, the highlands of Kabylie and Morocco, most of which even in Roman and Ottoman times remained largely independent, and where the Phoenicians never even penetrated beyond the coast. However, even these areas have been affected by some of the many invasions of North Africa, most recently including the French. Another major source of foreign influence, particularly in the Sahara, was the Trans-Atlantic slave trade route from West Africa, operated in part by the European commercial powers.

Berbers and the Islamic conquest

Unlike the conquests of previous religions and cultures, the coming of Islam, which was spread by Arabs, was to have pervasive and long-lasting effects on the Maghreb. The new faith, in its various forms, would penetrate nearly all segments of society, bringing with it armies, learned men, and fervent mystics, and in large part replacing tribal practices and loyalties with new social norms and political idioms.

Nonetheless, the Islamization and Arabization of the region were complicated and lengthy processes. Whereas nomadic Berbers were quick to convert and assist the Arab conquerors, not until the twelfth century, under the Almohad Dynasty, did the Christian and Jewish communities become totally marginalized.

Modern-day Berbers

The Berbers live mainly in Morocco (between 35%-60% of the population) and in Algeria (about 15%-33% of the population), as well as Libya and Tunisia, though exact statistics are unavailable[3]; see Berber languages. Most North Africans who consider themselves Arab also have significant Berber ancestry[4]. Prominent Berber groups include the Kabyles of northern Algeria, who number approximately 4 million and have kept, to a large degree, their original language and culture; and the Chleuh (francophone plural of Arabic "Shalh" and Tashelhiyt "ašəlḥi") of south Morocco, numbering about 8 million. Other groups include the Riffians of north Morocco, the Chaouia of Algeria, and the Tuareg of the Sahara. There are approximately 3 million Berber immigrants in Europe, especially the Riffians and the Kabyles in the Netherlands and France. Some proportion of the inhabitants of the Canary Islands are descended from the aboriginal Guanches—usually considered to have been Berber—among whom a few Canary Islander customs, such as the eating of gofio, originated.

Although stereotyped in the West as nomads, most Berbers were in fact traditionally farmers, living in the mountains relatively close to the Mediterranean coast, or oasis dwellers; the Tuareg and Zenaga of the southern Sahara, however, were nomadic. Some groups, such as the Chaouis, practiced transhumance.

Political tensions have arisen between some Berber groups (especially the Kabyle) and North African governments over the past few decades, partly over linguistic and cultural issues; for instance, in Morocco, giving children Berber names was banned.

Amazigh & Berber

Historically, it is not clear how the name "Berber" evolved, supposedly from the word "barbarian". The Berbers were known as "Libyans" to the ancient Greeks, and they were known under many names, like "Numidians" and "Moors", to the Romans.

Due to the fact that the Berbers were called "El-Barbar" by the Arabs, it is very probable that the modern European languages adopted it from the Arabic language. The Arabs didn't use the name "El-Barbar" as a negative, not being aware of the origin of that name; they supposedly created some myths or stories about the name. The most notorious myth considers "Barbar" as an ancestor of the Berbers. According to that myth, the Berbers were the descendants of Ham, the son of Noah, the son of Barbar, the son of Tamalla, the son of Mazigh, the son of Canon... [Ibn Khaldun/ The History of Ibn Khaldun - Chapter III].

The fact that the name "Berber" is a strange name to the Berbers led to confusion. Some sources claimed that the Berbers are several ethnic groups who are not related to each other. That is not accurate, because the Berbers refer to themselves as "Imazighen" in Morocco, as well as Libya, Egypt (Siwa) and other parts in North Africa.

Not only the origin of the name "Berber" is unclear, but also the name "Amazigh". The most common explanation is that the name goes back to the Egyptian period when the Ancient Egyptians mentioned an ancient Libyan tribe called Meshwesh. The Meshwesh are supposed by some scholars to be the same ancient Libyan tribe that was mentioned as "Maxyans" by the Greek Historian Herodotus.

Libyans & Numidians

Both names, "Amazigh" and "Berber", are relatively recent names in historical sources, since the name "Berber" appeared first in Arab-islamic sources, and the name "Amazigh" was never used in ancient sources. It is no less important to keep in mind that the Berbers were known by various names in different periods.

The first reference to the Ancient Berbers goes back to a very ancient Egyptian period. They were mentioned in the pre-dynastic period, on the so-called " Stele of Tehenou" which is still preserved in the Cairo museum in Egypt. That tablet is considered to be the oldest source wherein the Berbers have been mentioned. The second source is known as The Stele of king Narmer. This tablet is newer than the first source, and it depicted the Tehenou as captives.

The second oldest name is Tamahou. This name was mentioned for the first time in the period of the first king of the "Sixth Dynasty" and was referred to in other sources after that period. According to Oric Bates, those people were white-skinned, blondish and with blue eyes.

In the Greek period the Berbers were mainly known as "The Libyans" and their lands as "Libya" that extended from modern Morocco to the western borders of ancient Egypt [Modern Egypt contains Siwa, part of historical Libya, that still speaks the Berber language].

During the Roman period, the Berbers would become known as Numidians, Maures and Getulians, according to their tribes or kingdoms. The Numidians founded complicated and organized tribes, and thereafter they began to build a stronger kingdom. Most scholars believe that "Alyamas" was the first king of the Numidian kingdom [Mohammed Chafik/ Highlights of thirty-three centuries of the history of Imazighen]. Massinissa was the most famous Numidian king, who made Numidia a strong and civilized kingdom.

The Berbers and their languages

There are between 14 and 25 million speakers of Berber languages in North Africa, principally concentrated in Morocco and Algeria but with smaller communities as far east as Egypt and as far south as Burkina Faso.

Their languages, the Amazigh languages / Berber languages, form a branch of the Afroasiatic linguistic family comprising many closely related varieties, including Tarifit, Kabyle language or Taqbaylit and Tashelhiyt, with a total of roughly 14-25 million speakers. A frequently used generic name for all Berber languages is Tamazight, not to be confused with the language found in the High and Middle Atlas or Rif.

Currently, Berber is a "national" language in Algeria and is taught in some Berber speaking areas as a non-compulsory language. In Morocco, Berber has no official status, but is now taught as a compulsory language regardless of the area or the ethnicity. Berber is a spoken language and is rarely seen in writing.

Religions and beliefs

Berbers are predominantly Sunni Muslim, most belonging to the Maliki madhhab, while the Mozabites, Djerbans, and Nafusis of the northern Sahara are Ibadi Muslim. Sufi tariqas are common in the western areas, but rarer in the east; marabout cults were traditionally important in most areas.

Before their conversion to Islam, some Berber groups had converted to Christianity (often Donatist) or Judaism, while others had continued to practise traditional polytheism.

Under the influence of Islamic culture, some syncretic religions briefly emerged, as among the Berghouata, only to be replaced by Islam.

See also

Template:CommonsCat

- Berber Jews

- Kabylie, a coastal Berber area, inhabited By Kabyles.

- Zenata, ancestors of Riffis.

- Senhaja, ancestors of Souss Chleuhs.

- Masmouda, ancestors of Atlas Chleuhs

- Tuareg, a Saharan Berber group.

- Berber languages

- Barbary Coast

- Tamazgha, Berber name for North Africa.

- Berber mythology

- Berberism

- Arabized Berber

Footnotes

- ↑ Lexicon Universal Encyclopedia, 1989

Further Reading

- Brett, Michael; & Fentress, Elizabeth, The Berbers. Oxford, England & Cambridge, USA, Blackwell Publishing, 1996, ISBN 0631168524 OCLC: 31077775

- Ehret, Christopher, The Civilizations of Africa: A History to 1800, Charlottesville, Va, University Press of Virginia, 2002, ISBN 0813920841 OCLC: 48176919

- Celenko, Theodore, Egypt in Africa, Indianapolis, Ind. Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1996, ISBN 0936260645

- Briggs, Lloyd Cabot, The stone age races of northwest Africa Cambridge, Mass., Peabody Museum, 1955, OCLC: 757768

- Hiernaux,Jean, The people of Africa (People of the world series), Scribner, New York, 1975, ISBN 0684140403 OCLC: 0684140438

- Britannica 2004

- Encarta 2005

- Blanc, Saint Hiliaire, Grammaire de la Langue Basque (d'apres celle de Larramendi), Lyons & Paris, 1854, OCLC: 15031883

- Entwistle, W. J. The Spanish Language, (as cited in Michael Harrison's work, 1974.) London, 1936

- Gans, Eric Lawrence, The origin of language : a formal theory of representation Univ. of California Press, Berkeley, 1981, ISBN 0520042026 OCLC: 6603145

- Geze, Louis, Elements de Grammaire Basque, Beyonne, 1873, OCLC: 5087230

- Hachid, Malika, Les premiers Berbères : entre Méditerranée, Tassili et Nil, Edisud, 2001, ISBN 2744902276 OCLC: 45647361

- Hagan, Helene E., The Shining Ones: an Etymological Essay on the Amazigh Roots of Ancient Egyptian Civilisation. XLibris, US, 2001, ISBN 1401024122 0738825670 OCLC: 50084510

- Hagan, Helene E. Tuareg Jewelry: Traditional Patterns and Symbols, XLibris, 2006

- Harrison, Michael,The Roots of Witchcraft, Citadel Press, Secaucus, N.J., 1974

- Hualde, J. I., Basque Phonology, Routledge, London & New York, 1991, ISBN 0415056551 OCLC: 22767008

- Martins, J. P. de Oliveira, A History of Iberian Civilization, New York, Cooper Square Publishers, 1969 (©1930), ISBN 0815403003 OCLC: 26165

- Osborn, Henry Fairfield, Men of the old stone age, their environment, life and art, New York, C. Scribner, 1916 (1915), OCLC: 869341

- Renan, Ernest, De l'Origine du Langage, Paris, France-Expansion, 1973, OCLC: 56270302

- Ripley, W. Z., The Races of Europe, D. Appleton & Co., New York, 1899, OCLC: 871780

- Ryan, William & Pitman, Walter, Noah's Flood: The new scientific discoveries about the event that changed history, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1998, ISBN 0684810522 OCLC: 40076603

- Saltarelli, Mario, Basque, London, New York, Croom Helm, 1988, ISBN 0709933533 OCLC: 17441710

- Silverstein, Paul A., Algeria in France: Transpolitics, Race, and Nation, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2004, ISBN 0253344514 0253217121 OCLC: 54392646

External links

- Richard L. Smith, Ferrum College, What Happened to the Ancient Libyans? Chasing Sources across the Sahara from Herodotus to Ibn Khaldun Journal of World History, vol. 14, no. 4, 2003 Online article. retrieved 01/01/2007

- Amazigh Startkabel Links to Amazigh Sites. retreived 01/01/2007

- Amar Almasude, The New Mass Media and the Shaping of Amazigh Identity Revitalizing Indigenous Languages, retrieved 01/01/2007

- Jose Barrios Garca, Sept 1997 Number Systems and Calendars of the Berber Populations of Grand Canary and Tenerife Archaeoastronomy & Ethnoastronomy News, retrieved 01/01/2007

- Encyclopedia of the Orient — Berbers, retrieved 01/01/2007

- Ivan Sache, February 2004 Flags of the World — Berbers/Imazighen, retrieved 01/01/2007

- Berber World Online www.mondeberbère.com retrieved 01/01/2007

- Mark Hannaford Photo Gallery Photo Gallery of Berbers and Touregs from Erg Chebbi area of Moroccan Sahara retrieved 01/01/2007

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.