History of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a major shift of technological, socioeconomic, and cultural conditions that occurred in the late 18th century and early 19th century in some Western countries. It began in Britain and spread throughout the world, a process that continues as industrialisation. The onset of the Industrial Revolution marked a major turning point in human social history, comparable to the invention of farming or the rise of the first city-states; almost every aspect of daily life and human society is, eventually, in some way influenced.

In the latter half of the 1700's the manual labour based economy of the Kingdom of Great Britian began to be replaced by one dominated by industry and the manufacture of machinery. It started with the mechanisation of the textile industries, the development of iron-making techniques and the increased use of refined coal. Once started it spread. Trade expansion was enabled by the introduction of canals, improved roads and railways. The introduction of steam power (fuelled primarily by coal) and powered machinery (mainly in textile manufacturing) underpinned the dramatic increases in production capacity.[1] The development of all-metal machine tools in the first two decades of the 19th century facilitated the manufacture of more production machines for manufacturing in other industries. The effects spread throughout Western Europe and North America during the 19th century, eventually affecting most of the world. The impact of this change on society was enormous.[2] "What caused the Industrial Revolution?" remains the most important unanswered question in social science.

The first Industrial Revolution merged into the Second Industrial Revolution around 1850, when technological and economic progress gained momentum with the development of steam-powered ships, railways, and later in the nineteenth century with the internal combustion engine and electrical power generation.

The period of time covered by the Industrial Revolution varies with different historians. Eric Hobsbawm held that it 'broke out' in the 1780s and was not fully felt until the 1830s or 1840s,[3] while T. S. Ashton held that it occurred roughly between 1760 and 1830.[4] Some twentieth century historians such as John Clapham and Nicholas Crafts have argued that the process of economic and social change took place gradually and the term revolution is not a true description of what took place. This is still a subject of debate amongst historians.[5][6]

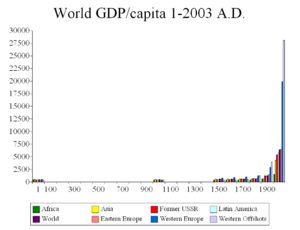

As might be expected of such a large social change, the Industrial Revolution had a major impact upon wealth. It has been argued that GDP per capita was much more stable and progressed at a much slower rate until the Industrial Revolution and the emergence of the modern capitalist economy, and that it has since increased rapidly in capitalist countries.[7]

Nomenclature

The term Industrial Revolution applied to technological change was common in the 1830s. Louis-Auguste Blanqui in 1837 spoke of la révolution industrielle. Friedrich Engels in The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 spoke of "an industrial revolution, a revolution which at the same time changed the whole of civil society."

In his book Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society, Raymond Williams states in the entry for Industry: The idea of a new social order based on major industrial change was clear in Southey and Owen, between 1811 and 1818, and was implicit as early as Blake in the early 1790s and Wordsworth at the turn of the century.

Credit for popularising the term may be given to Arnold Toynbee, whose lectures given in 1881 gave a detailed account of the process.

Causes

The causes of the Industrial Revolution were complex and remain a topic for debate, with some historians seeing the Revolution as an outgrowth of social and institutional changes brought by the end of feudalism in Britain after the English Civil War in the 17th century. As national border controls became more effective, the spread of disease was lessened, therefore preventing the epidemics common in previous times. The percentage of children who lived past infancy rose significantly, leading to a larger workforce. The Enclosure movement and the British Agricultural Revolution made food production more efficient and less labour-intensive, forcing the surplus population who could no longer find employment in agriculture into cottage industry, for example weaving, and in the longer term into the cities and the newly developed factories. The colonial expansion of the 17th century with the accompanying development of international trade, creation of financial markets and accumulation of capital are also cited as factors, as is the scientific revolution of the 17th century.

Technological innovation was the heart of the industrial revolution and the key enabling technology was the invention and improvement of the steam engine.[8]

The historian, Lewis Mumford has proposed that the Industrial Revolution had its origins in the early Middle Ages, much earlier than most estimates. He explains that the model for standardised mass production was the printing press and that "the archetypal model for the [industrial era] was the clock". He also cites the monastic emphasis on order and time-keeping, as well as the fact that Mediaeval cities had at their centre a church with bell ringing at regular intervals as being necessary precursors to a greater synchronisation necessary for later, more physical manifestations such as the steam engine.

The presence of a large domestic market should also be considered an important driver of the Industrial Revolution, particularly explaining why it occurred in Britain. In other nations, such as France, markets were split up by local regions, which often imposed tolls and tariffs on goods traded amongst them.[9]

Governments' grant of limited monopolies to inventors under a developing patent system (the Statute of Monopolies 1623) is considered an influential factor. The effects of patents, both good and ill, on the development of industrialisation are clearly illustrated in the history of the steam engine, the key enabling technology. In return for publicly revealing the workings of an invention, the patent system rewards inventors by allowing, e.g, James Watt to monopolise the production of the first steam engines, thereby enabling inventors and increasing the pace of technological development. However monopolies bring with them their own inefficiencies which may counterbalance, or even overbalance, the beneficial effects of publicizing ingenuity and rewarding inventors[10]. Watt's monopoly may have prevented other inventors, such as Richard Trevithick, William Murdoch or Jonathan Hornblower, from introducing improved steam engines thereby retarding the industrial revolution by up to 20 years[11].

Causes for occurrence in Europe

One question of active interest to historians is why the Industrial Revolution started in 18th century Europe and not in other parts of the world in the 18th century, particularly China, India, and the Middle East, or at other times like in Classical Antiquity[12] or the Middle Ages.[13] Numerous factors have been suggested, including ecology, government, and culture. Benjamin Elman argues that China was in a high level equilibrium trap in which the non-industrial methods were efficient enough to prevent use of industrial methods with high costs of capital. Kenneth Pomeranz, in the Great Divergence, argues that Europe and China were remarkably similar in 1700, and that the crucial differences which created the Industrial Revolution in Europe were sources of coal near manufacturing centres, and raw materials such as food and wood from the New World, which allowed Europe to expand economically in a way that China could not.[14] However, most historians contest the assertion that Europe and China were roughly equal because modern estimates of per capita income on Western Europe in the late 18th century are of roughly 1,500 dollars in purchasing power parity (and Britain had a per capita income of nearly 2,000 dollars[15] ) whereas China, by comparison, had only 450 dollars. Also, the average interest rate was about 5% in Britain and over 30% in China, which illustrates how capital was much more abundant in Britain; capital that was available for investment.

Some historians such as David Landes[16] and Max Weber credit the different belief systems in China and Europe with dictating where the revolution occurred. The religion and beliefs of Europe were largely products of Judaeo-Christianity, and Greek thought. Conversely, Chinese society was founded on men like Confucius, Mencius, Han Feizi (Legalism), Lao Tzu (Taoism), and Buddha (Buddhism). The key difference between these belief systems was that those from Europe focused on the individual, while Chinese beliefs centred around relationships between people. The family unit was more important than the individual for the large majority of Chinese history, and this may have played a role in why the Industrial Revolution took much longer to occur in China. There was the additional difference as to whether people looked backwards to a reputedly glorious past for answers to their questions or looked hopefully to the future. Furthermore, Western European peoples had experienced the Renaissance and Reformation; other parts of the world had not had a similar intellectual breakout, a condition that holds true even into the 21st century.

Regarding India, the Marxist historian Rajani Palme Dutt has been quoted as saying, "The capital to finance the Industrial Revolution in India instead went into financing the Industrial Revolution in England." [17] In contrast to China, India was split up into many competing kingdoms, with the three major ones being the Marathas, Sikhs and the Mughals. In addition, the economy was highly dependent on two sectors—agriculture of subsistence and cotton, and technical innovation was non-existent. The vast amounts of wealth were stored away in palace treasuries, and as such, were easily moved to Britain.

Causes for occurrence in Britain

The debate about the start of the Industrial Revolution also concerns the massive lead that Great Britain had over other countries. Some have stressed the importance of natural or financial resources that Britain received from its many overseas colonies or that profits from the British slave trade between Africa and the Caribbean helped fuel industrial investment. It has been pointed out, however, that slavery provided only 5% of the British national income during the years of the Industrial Revolution.[18]

Alternatively, the greater liberalisation of trade from a large merchant base may have allowed Britain to produce and utilise emerging scientific and technological developments more effectively than countries with stronger monarchies, particularly China and Russia. Britain emerged from the Napoleonic Wars as the only European nation not ravaged by financial plunder and economic collapse, and possessing the only merchant fleet of any useful size (European merchant fleets having been destroyed during the war by the Royal Navy[19]). Britain's extensive exporting cottage industries also ensured markets were already available for many early forms of manufactured goods. The conflict resulted in most British warfare being conducted overseas, reducing the devastating effects of territorial conquest that affected much of Europe. This was further aided by Britain's geographical position— an island separated from the rest of mainland Europe.

Another theory is that Britain was able to succeed in the Industrial Revolution due to the availability of key resources it possessed. It had a dense population for its small geographical size. Enclosure of common land and the related Agricultural Revolution made a supply of this labour readily available. There was also a local coincidence of natural resources in the North of England, the English Midlands, South Wales and the Scottish Lowlands. Local supplies of coal, iron, lead, copper, tin, limestone and water power, resulted in excellent conditions for the development and expansion of industry. Also, the damp, mild weather conditions of the North West of England provided ideal conditions for the spinning of cotton, providing a natural starting point for the birth of the textiles industry.

The stable political situation in Britain from around 1688, and British society's greater receptiveness to change (when compared with other European countries) can also be said to be factors favouring the Industrial Revolution. In large part due to the Enclosure movement, the peasantry was destroyed as significant source of resistance to industrialisation, and the landed upper classes developed commercial interests that made them pioneers in removing obstacles to the growth of capitalism.[20]

Protestant work ethic

Another theory is that the British advance was due to the presence of an entrepreneurial class which believed in progress, technology and hard work.1 The existence of this class is often linked to the Protestant work ethic (see Max Weber) and the particular status of dissenting Protestant sects, such as the Quakers, Baptists and Presbyterians that had flourished with the English Civil War. Reinforcement of confidence in the rule of law, which followed establishment of the prototype of constitutional monarchy in Britain in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and the emergence of a stable financial market there based on the management of the national debt by the Bank of England, contributed to the capacity for, and interest in, private financial investment in industrial ventures.

Dissenters found themselves barred or discouraged from almost all public offices, as well as education at England's only two Universities at the time (although dissenters were still free to study at Scotland's four universities). When the restoration of the monarchy took place and membership in the official Anglican church became mandatory due to the Test Act, they thereupon became active in banking, manufacturing and education. The Unitarians, in particular, were very involved in education, by running Dissenting Academies, where, in contrast to the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge and schools such as Eton and Harrow, much attention was given to mathematics and the sciences—areas of scholarship vital to the development of manufacturing technologies.

Historians sometimes consider this social factor to be extremely important, along with the nature of the national economies involved. While members of these sects were excluded from certain circles of the government, they were considered fellow Protestants, to a limited extent, by many in the middle class, such as traditional financiers or other businessmen. Given this relative tolerance and the supply of capital, the natural outlet for the more enterprising members of these sects would be to seek new opportunities in the technologies created in the wake of the Scientific revolution of the 17th century. {{credits|Industrial_Revolution|

- ↑ Business and Economics. Leading Issues in Economic Development, Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-511589-9 Read it

- ↑ Russell Brown, Lester. Eco-Economy, James & James / Earthscan. ISBN 1-85383-904-3 Read it

- ↑ Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Revolution: Europe 1789–1848, Weidenfeld & Nicolson Ltd. ISBN 0-349-10484-0

- ↑ Joseph E Inikori. Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01079-9 Read it

- ↑ Rehabilitating the Industrial Revolution Maxine Berg, Pat Hudson, Economic History Review, New Series, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Feb., 1992), pp. 24-50 doi:10.2307/2598327

- ↑ Rehabilitating the Industrial Revolution by Julie Lorenzen , Central Michigan University. Accessed November 2006

- ↑ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis [1] Accessed 13 November 2006.

- ↑ Hudson, Pat. The Industrial Revolution, Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-7131-6531-6 Read it

- ↑ Deane, Phyllis. The First Industrial Revolution, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29609-9 Read it

- ↑ Eric Schiff, Industrialization without national patents: the Netherlands, 1869-1912; Switzerland, 1850-1907, Princeton University Press, 1971.

- ↑ Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine, Economic and Game Theory Against Intellectual Monopoly,

PDF, page 2.

PDF, page 2.

- ↑ Why No Industrial Revolution in Ancient Greece? J. Bradford DeLong, Professor of Economics, University of California at Berkeley , September 20, 2002. Accessed January 2007.

- ↑ The Origins of the Industrial Revolution in England | The History Guide, Steven Kreis, October 11, 2006 - Accessed January 2007

- ↑ Immanuel Chung-Yueh Hsu. The Rise of Modern China, Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-512504-5 Read it

- ↑

PDF Jan Luiten van Zanden, International Institute of Social History/University of Utrecht. May 2005. Accessed January 2007

PDF Jan Luiten van Zanden, International Institute of Social History/University of Utrecht. May 2005. Accessed January 2007

- ↑ Landes, David (1999) Wealth And Poverty Of Nations pub WW Norton, ISBN 0393318885

- ↑ South Asian History -Pages from the history of the Indian subcontinent: British rule and the legacy of colonisation. Rajni-Palme Dutt India Today (Indian Edition published 1947); Accessed January 2007

- ↑ http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/historyonline/con_economic.cfm Was slavery the engine of economic growth? Digital History

- ↑ The Royal Navy itself may have contributed to Britain’s industrial growth. Among the first complex industrial manufacturing processes to arise in Britain were those that produced material for British warships. For instance, the average warship of the period used roughly 1000 pulley fittings. With a fleet as large as the Royal Navy, and with these fittings needing to be replaced ever 4 to 5 years, this created a great demand which encouraged industrial expansion. The industrial manufacture of rope can also be see as a similar factor.

- ↑ Barrington Moore, Jr., Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World, pp. 29-30, Boston, Beacon Press, 1966.