Maori

| MÄori | |

|---|---|

| |

| Te Puni, nineteenth-century MÄori chief | |

| Total population | approx. 680,000 |

| Regions with significant populations | New Zealand, Australia, United Kingdom, United States, Canada |

| Language | MÄori, English |

| Religion | MÄori religion, Christianity |

The word MÄori refers to the indigenous people of New Zealand and their language. Both the term and the people are a hybrid of various Polynesian cultures, and are thought to have arrived in New Zealand more than one thousand years ago. The Maori people are well known for their distinctive traditional full-body and facial tattooing. They have a unique status in the world as indigenous people who have full legal rights.

Despite experiences with racism and threats to their culture by assimilation, the MÄori culture has sustained significant revival and consolidation. They contribute to many aspects of the economy of New Zealand, including tourism, although they continue to suffer social problems with disproportionately low health and education and high rates of crime and prison statistics. Nevertheless, the success of the MÄori in maintaining their culture and identity in a country dominated by European colonials offers hope for other indigenous populations and a world in which widely differing ethnic groups can live together harmoniously.

Terms

In the MÄori language the word mÄori means "normal," "natural," or "ordinary." In legends and other oral traditions, the word distinguished ordinary mortal human beings from deities and spirits. MÄori has cognates in other Polynesian languages such as the Hawaiian Maoli, the Tahitian Maohi, and the Cook Islands MÄori which all share similar meanings. The contemporary English meanings are "native," "indigenous," or "aboriginal."

Early European visitors to the islands of New Zealand referred to the people they found there variously as "Indians," "aborigines," "natives," or "New Zealanders." MÄori remained the term used by MÄori to describe themselves in a pan-tribal sense. In 1947, the Department of Native Affairs was renamed the Department of MÄori Affairs to recognize this.

The term Tangata whenua (literally, "people of the land") is often used by MÄori to describe themselves in such a way that emphasizes their relationship with a particular area of landâa tribe may be tangata whenua in one area, but not another. The term can also be used to describe MÄori as a whole in relation to New Zealand as a whole.

Aotearoa is the most widely known and accepted MÄori name for New Zealand. This usage is post-colonial. In pre-colonial times, MÄori did not have a commonly-used name for the whole New Zealand archipelago. In fact, until the twentieth century, Aotearoa was used to refer to the North Island only.

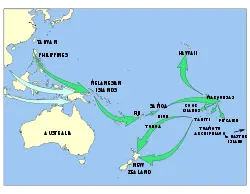

MÄori origins

It is thought that New Zealand was one of the last areas on Earth to be settled by humans. Archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests that probably several waves of migration came from Eastern Polynesia to New Zealand between 800 and 1300 C.E..[1] MÄori origins relate to those of their Polynesian ancestors. MÄori oral history describes the arrival of the ancestors from Hawaiki (a mythical homeland in tropical Polynesia) by large ocean-going canoes (waka). Migration accounts vary among MÄori tribes (iwi), whose members can identify with different waka in their genealogies or whakapapa.

No credible evidence exists of human settlement in New Zealand prior to the Polynesian voyagers; on the other hand, compelling evidence from archaeology, linguistics, and physical anthropology indicates that the first settlers came from East Polynesia and became the MÄori.

History

Before 1840

European settlement of New Zealand occurred relatively recently. New Zealand historian Michael King has described the MÄori as "the last major human community on earth untouched and unaffected by the wider world."[2]

The early European explorers, including Abel Tasman (who arrived in 1642) and Captain James Cook (who first visited in 1769), reported encounters with MÄori. These early reports described the MÄori as a fierce and proud warrior race. Inter-tribal warfare occurred frequently in this period, with the victors enslaving or in some cases eating the vanquished.

From as early as the 1780s, MÄori encountered European sealers and whalers; some even crewed on the foreign ships. A continuous trickle of escaped convicts from Australia and deserters from visiting ships also exposed the indigenous New Zealand population to outside influences.

By 1830, estimates placed the number of PÄkehÄ (Europeans) living among the MÄori as high as 2,000. The newcomers' status varied from slaves through to high-ranking advisors, from prisoners to those who abandoned European culture and identified themselves as MÄori. Many MÄori valued PÄkehÄ for their ability to describe European skills and culture and their ability to obtain European items in trade, particularly weaponry. These Europeans "gone native" became known as PÄkehÄ MÄori. When Pomare led a war party against Titore in 1838, he had 132 PÄkehÄ mercenaries among his warriors. Frederick Edward Maning, an early settler, wrote two colorful accounts of life at that time, which have become classics of New Zealand literature: Old New Zealand and History of the War in the North of New Zealand against the Chief Heke.[3]

During this period the acquisition of muskets by those tribes in close contact with European visitors destabilized the existing balance of power between MÄori tribes, and there ensued a period of bloody inter-tribal warfare, known as the Musket Wars, which resulted in the effective extermination of several tribes and the driving of others from their traditional territory. European diseases also killed a large but unknown number of MÄori during this period; estimates vary between ten and 50 percent of their population.

In the 1830s, with increasing European missionary activity and conversion to Christianity, as well as the perceived European lawlessness within their own settlements, the British Crown, as a predominant world power, came under pressure to intervene. At this same time many British people were indignant that their presence had discouraged the native MÄori from their traditional leisure activities, and some Europeans were instrumental in helping support the continuation of native culture.

1840 to 1890

As a result of the unrest, Britain dispatched William Hobson with instructions to take possession of New Zealand. Before he arrived, Queen Victoria annexed New Zealand by royal proclamation in January 1840. On arrival in February, Hobson negotiated the Treaty of Waitangi with the northern chiefs. Many other MÄori chiefs (though by no means all) subsequently signed this treaty. It made the MÄori British subjects in return for a guarantee of property rights and tribal autonomy.

Both parties entered the Treaty-based partnership with enthusiasm, despite regrettable exceptional incidents. MÄori formed substantial businesses, supplying food and other products for domestic and overseas markets.

Among the first Europeans to learn the MÄori language and record MÄori mythology was George Grey, Governor of New Zealand from 1845 to 1855 and 1861 to 1868. In 1851, Herman Melville used a character in his classic novel, Moby Dick who is undoubtedly patterned after the MÄori. The mysterious Queequeg, who sports the traditional MÄori tattooing is portrayed as a savage cannibal. The intrigue that he elicits from the Europeans in both his savage and civilized behavior, and being very strong, intelligent, and prescient reflects the general intrigue with which Europeans regarded the MÄori.

In the 1860s, disputes over questionable land purchases and the attempts of MÄori in the Waikato to establish what some perceived as a rival British-style system of royalty led to the New Zealand land wars. Although these resulted in relatively few deaths, the colonial government confiscated large tracts of tribal land as punishment for what they termed as rebellion, in some cases without reference to whether the tribe involved actually participated in the warfare. Some tribes actively fought against the Crown, while others (known as kupapa) fought in support of the Crown. A passive resistance movement developed at the settlement of Parihaka in Taranaki, but Crown troops dispersed its participants in 1881.

With the loss of much of their land, MÄori went into a period of decline, and by the late nineteenth century most people believed that the MÄori population would cease to exist as a separate race and become assimilated into the European population.

Twentieth century

The predicted decline of the MÄori population did not occur; instead there was a recovery. From the beginning of European interaction, there were many Europeans who joined MÄori culture and the converse of MÄori who integrated into European culture. Despite a substantial level of intermarriage between the MÄori and European populations, many MÄori retained their cultural identity.

From the late nineteenth century, a number of successful MÄori politicians emerged. Men such as James Carroll, Apirana Ngata, Te Rangi Hiroa, and Maui Pomare were skilled in the arts of PÄkehÄ politics; at one point Carroll was Acting Prime Minister. This group, known as the Young MÄori Party aimed to revitalize their people after the devastation of the previous century. For them, this involved MÄori adopting European ways of life such as Western medicine and education.

However, Ngata in particular also wished to preserve traditional MÄori culture, especially the arts. Ngata was a major force behind the revival of arts such as kapa haka and carving. He also enacted a program of land development which helped many iwi retain and develop their land.

During World War I, Princess Te Puea encouraged some MÄori not to enlist. She supported Kingitanga (the MÄori king movement) and the revival of numerous native pastimes and cultural activities, including sports.

Culture

Language

The MÄori language is known as Te Reo MÄori, or shortened to Te Reo (literally, the language). Today it is an official language of New Zealand. Originally from eastern Polynesia, it is closely related to Tahitian and Cook Islands MÄori; slightly less closely to Hawaiian and Marquesan; and more distantly to the languages of Western Polynesia, including Samoan, Niuean, and Tongan.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, it looked like Te Reo as well as other aspects of MÄori life would disappear. In the 1980s however, government sponsored schools taught Te Reo, educating those of European descent as well as MÄori. Since then, Te Reo is universally known within MÄori communities and many of its phrases are in universal use.

There was originally no native writing system for MÄori. It has been suggested that the petroglyphs once used by the MÄori developed into a script similar to the Rongorongo of Easter Island. However, there is no evidence that these petroglyphs ever evolved into a true system of writing. Some distinctive markings among the kÅwhaiwhai (rafter paintings) of meeting houses were used as mnemonics in reciting whakapapa (genealogy) but again, there was no systematic relation between marks and meanings.

Missionaries brought the Roman alphabet around 1814, and Samuel Lee of Cambridge University worked with chief Hongi Hika and his junior relative Waikato to systematize the written language in 1820. The resultant phonetic spellings were remarkably successful. Written MÄori has changed little since then. Literacy was an exciting new concept that the MÄori embraced enthusiastically and which most MÄori had mastered by 1830.

Society

MÄori culture has many social customs, rituals, and traditions that are well known since they continue to be in use today.

MÄori protocol begins with the greeting of visitors to a marae (MÄori meeting grounds). This formal welcome is called powhiri and begins with wero (challenge). A warrior from the tangata whenua (hosts) challenges the manuhiri (guests) with a weapon like taiaha (a spear), and then lays down a token offering for them (often a small branch). The manuhiri then will pick it up. This shows their interdependency and acceptance of hospitality. Some of the host kuia (women) will perform a karanga (call/chant). Women from the guests will then respond as they move onto the marae in front of their men. Once inside the wharenui (meeting house) on the marae, mihimihi (greetings) and whaikorero (speeches) are made. To reinforce the good wishes of the speeches, waiata (songs) may be sung. It is usual for the guests to then present a koha (gift) to their hosts after greeting them with a hongiâthe ceremonial touching of noses. After this welcome, kai (food) may be shared.

MÄori have traced their lineages for some time using whakapapa rakau (a genealogical, carved staff) to count up to 18 successive generations in its carving. Most original whakapapa rakau averaged over a meter in length. Whakapapa is the actual recital of genealogy. Whakapapa means taking place in layers, which is how the various orders of genealogies are seen according to the MÄori. The rakau in whakapapa rakau is the staff itself being used when the whakapapa recital is taking place. These are wooden sticks, with knobs running down the shaft. The knobs on the genealogical staff serve to help the memory when a person is reciting the whakapapaâthe knobs representing the different ancestry.

The MÄori trace their descent back to the arrival of the first canoes from Hawaiiki (presumably near to Hawaii). The most famous wakas (canoes) were the Arawa, the Tainui, and the Mataatua. A descendant is an Uri, and the word waka means both "canoe" and/or "tribe" in the social sense of the word. Each waka is separated into iwi (tribes), being descended from each individual crew member. The whanau is a group of closely related persons from related tribes or sub-tribes. A number of whanau grouped together would become a sub-tribe, or hapu. When a hapu group came together, to form a tribe, it became iwi. A prefix to a tribal name would indicate the tribe, such as Ngati Toa.

The most important festival is To MÄori, the appearance of Matariki and Puanga (Rigel) to signal the end of one year, and the beginning of the next. Traditionally MÄori have recognized the rise of Matariki as the time to celebrate the New Year. Towards the end of May each year, Matariki rises in the lightening dawn, at the same place on the horizon as the rising sun. The MÄori New Year celebrations are held on the sighting of the next new moon. Matariki celebrations were held after the crops had been harvested and stored, whereupon hakari (huge feasts) and Nga-Mahi-a-te-Rehia (merry-making) continued for several weeks during respite from cultivation. This calendar thus has an odd cycle when taken in the perspective of the contemporary calendar followed by the western world.

Spirituality

MÄori believe all things are inter-connected and spiritual. Tapu is a force that is in all things, and has many meanings and references. It is the strongest force and means both "sacred" and "prohibited" as MÄori have a complex protocol on how to work with tapu. The origin for the term tapu and some applications are unclear today. Some purposes are to reinforce the social order but other reasons are seen to protect the environment that would benefit the whole community.

People, things, and places may be tapu, and if they are they should not be touched. In some cases, they should not even be approached except by suitable priests. Some things may be tapu at certain times, and not others. There are two main types of tapu; private and public. Private tapu concerns individuals, and public tapu concerns communities.

Whenever the tapu protocol was breached, it was a hara (violation) that could incur the wrath of the gods. If something tapu is touched, it can cause some of the mana (original life force) it contains to leak out. Certain objects are more tapu than others, and can be very dangerous. To prevent the wrath of the gods, death could be punishment for the breach thus saving the community from disaster. The French explorer Marion du Fresne was killed in 1772 for breaching a tapu.

There is a social hierarchy where in earlier times those of higher rank would not touch objects belonging to those of lower rank. It was believed they could be "polluted" in this way. Similarly, lower ranking people could not touch the belongings of higher ranking people, with a penalty of death. In earlier times a woman could not enter a chief's house unless a karakia (religious) ceremony was performed. An ariki (chief) and a tohunga (healer or priest) were lifelong tapu people.

All arts are tapu, with specific protocol on how to carve, weave, and so forth. Even game play has elements of tapu. All urupa (burial grounds)and wahi tapu (places of death) were always tapu, and these areas were often surrounded by a protective fence.

Noa, on the other hand, lifts the tapu from a person or object. Noa is similar to a blessing. Although essentially all MÄori today are Christian, tapu and noa remain part of the culture. The meaning has become much more social. Tapu observances are still in evidence concerning sickness, death, and burial. If one buys a souvenir at a tourist site, most people have noa for their object. Another example it that most people have a noa ceremony for a new home to ensure good fortune and safety.

Arts

Traditional arts such as carving, raranga (weaving), kapa haka (group performance), whaikorero (oratory), and moko (tattoo) are common throughout the country. Practitioners often follow the techniques of their ancestors, but today MÄori also includes contemporary arts such as film, television, poetry, theater, and hip-hop.

The haka is a traditional dance form of the Maori. It is a posture dance with shouted accompaniment, performed by a group. The All Blacks, the international rugby union team of New Zealand, perform a haka immediately prior to international matches. Over the years they have most commonly performed the haka Ka Mate. In the early decades of international rugby, they sometimes performed other haka, some of which were composed for specific tours.

Pre-European MÄori stories and legends were handed down orally and through weavings and carvings. Some surviving Te Toi Whakairo, or carving, is over 500-years-old. Tohunga Whakairo are the great carversâthe master craftsmen. A master carver is highly considered. The MÄori believed that the gods created and communicated through the Tohunga Whakairo. Carving has been a tapu art, subject to the rules and laws of tapu. Pieces of wood that fell aside as the carver worked were never thrown away, neither were they used for the cooking of food. Women were not permitted near Te Toi Whakairo.

Te Toi Whakairo differs from other Polynesian carving in that they prefer curves to straight lines. Many have distinctive koru spiral forms, similar to that of a curving stalk, or a bulb. The koru form represents the basis of the red, white and black rafter patterns. Various forms are often seen in the carving. Manaia is a side-faced and sometimes birdlike figure. This figure also exists in Easter Island, Hawaii, and South America. There is speculation about where the form originated, but some consensus that about 2,000 years early Polynesians and South Americas had some cultural exchange.

Marakihau is a deep sea taniwha (monster). It has a human form, but includes a long tongue that helped the Marakihau monsters swallow up canoes or men. Quite often a type of crown form was situated on the top of the head. In older carvings, there are many one-eyed human faces. The lizard is the only animal represented in MÄori carving and is revered. Unlike other depictions, the form of the lizard is never deformed.

MÄori weave baskets, floor mats, skirts, and cloaks from New Zealand flax (phormium tenax). There are more than 50 different varieties of this flax, and MÄori know exactly which is good for what usage. The first Polynesians brought the art of weaving and plaiting to New Zealand. Weaving techniques adapted, however, primarily because of the cooler climate.

The art of weaving, known as raranga, is more than simply skills and techniques. It embodies the spiritual values of MÄori people and the patterns are full of symbolism and hidden meanings. Raranga is used to produce household products like kete harakeke (flax basket) that are used every day by contemporary MÄori, as well as the ki (ball) for ki-o-rahi (traditional ball game), reminding them of their ancient culture and values.

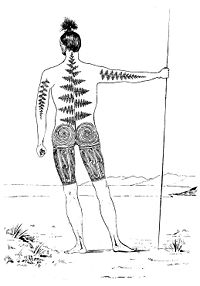

Tattoos

Tattooing came to New Zealand from other eastern Polynesian cultures, but is unique in that it is carved into the skin. This is done first, and next a chisel is dipped into a sooty type pigment such as burnt Kauri gum or burnt vegetable caterpillars. Then this is tapped into the skin. It is an extremely painful and long process. Because tattooing causes blood to run, the tohunga-ta-oko (tattoo craftsmen) are very tapu (sacred) people. Leaves from the native Karaka tree are placed over the swollen tattoo cuts to hasten the healing process. During the tattooing process, flute music and chant poems were performed to help soothe the pain.

There were also certain prohibitions during the process. For the facial tattoo in particular, sexual intimacy and the eating of solid foods were forbidden. Liquid food and water were drained into a wooden funnel, ensuring that no contamination would contact the wounds.

The head is considered the most sacred part of the body, and most tattoos are facial with more on men than women. The full faced tattoo is very time consuming, and a good tattoo craftsman carefully studies a person's bone structure before commencing his art.

Although the tattoos were mainly facial, the North Auckland warriors included swirling double spirals on both buttocks, often leading down their legs until the knee. Women were not as extensively tattooed as the men. Their upper lips were outlined, usually in dark blue. The nostrils were also very finely incised. The chin Moko (pattern) was always the most popular, and continues to be practiced.

Tattooing commenced at puberty, with many rites and rituals. The tattoo marked both rites of passage and important events in a person's life. All high-ranking MÄori were tattooed, and those who went without tattoos were seen as people of no social status.

Moko is like an identity card, or passport. For men, the Moko showed rank, status, and their ferocity or virility. The position of power and authority could be instantly recognized in his Moko. Certain other outward signs, combined with a particular Moko, would define the "identity card" of a person. Since it was a great insult not to recognize someone of high rank, this could lead to utu (vengeance).

The position of the Moko also indicates attributes of the bearer. For men, the center of the forehead indicates rank, around the brows shows position, the eyes and nose areas show hapu rank, the first and second marriages are shown on the temples, the individuality under the nose, the work in the cheek area, and the birth status on the jaw. Ancestry is shown on each side of the face with the left generally being for the father's side and the right the mother's. This was to be determined before the Moko could be devised. If one side of a person's ancestry had no rank, then that side of the face would have no Moko design. Likewise, if there is no Moko design in the center forehead area, this means the wearer either has no rank, or has not inherited rank.

Sports

Games and all arts of pleasure, were an integral part of MÄori life. Originally sports were part of everyday life, and not restricted to a time or a place. However, there were special times and events such as the Matariki festivities of the New Year where game play was exceptional. Throughout pre-European New Zealand, the great Matariki Festivals were the annual catalyst for a broad spectrum of game development, problem solving, invention, and experimentation.

Without exception, historically the greatest emphasis was on kite flying. In kite flying, there is a highly symbolic connection to Matarikiâa small cluster of stars, also known as Pleiades. Kites were historically seen as connectors between the heaven and the earth and the marking of the new year. There were many different types of kites, with many purposes. Men women and children of all status participated in the testing and development of new kites.

Ki-o-Rahi is a traditional, pre-European MÄori ball game that is played on a circular field. It is a fast running contact sport, involving imaginative handling and swift inter-passing of a ki (ball), which traditionally was woven from flax.[4] It is a fast-paced sport incorporating skills found in rugby union, netball, and touch football. Two teams of seven players play on a circular field divided into zones, and score points by touching the pou (boundary markers) and hitting a central tupu or target.

While sports are sometimes used as a substitute for war, pre-European MÄori brought the two together by playing Ki-o-Rahi against their enemies. âThey would stop the battle, play this game as a means of showing their prowess, and go back to the battle.â[5]

Before the arrival of Europeans, Ki-o-Rahi was played by MÄori throughout Aotearoa/New Zealand. With the multiple influences of the missionaries, other European influence and wars, most native leisure activity had disappeared by 1870. This is about the same time that Rugby was introduced, which MÄori took to enthusiastically and have played well professionally for New Zealand. Ki-o-Rahi was revived during World War I, and is played in a modified version today.

Contemporary life

Since the 1960s, the MÄori have secured their cultural revival. Government recognition of the growing political power of MÄori combined with political activism have led to a limited redress for unjust confiscation of land and for the violation of other property rights. The State set up the Waitangi Tribunal, a body with the powers of a Commission of Inquiry, to investigate and make recommendations on such issues. As a result of the redress paid to many iwi (tribes), MÄori now have significant interests in the fishing and forestry industries.

In many areas of New Zealand, MÄori language lost its role as a living community language (used by significant numbers of people) in the post-World War II years. In tandem with calls for sovereignty and the righting of social injustices from the 1970s onwards, many New Zealand schools now teach MÄori culture and language (te reo), and pre-school kohanga reo (literally: "language nests") have started which teach exclusively in MÄori. These now extend right through secondary schools. In 2004 MÄori Television, a government-funded television station committed to broadcasting primarily in te reo, began broadcasting. MÄori language, enjoys the equivalent status de jure as English in government and law, although the language continues to be marginalized in mainstream use. At the time of the 2006 Census, Maori was the second-most widely spoken language after English, with four percent of New Zealanders able to speak Maori to at least a conversational level.

In 2005, a worldwide survey suggested that MÄori have the world's fourth-highest rate of entrepreneurship.[6] The success of the Tamaki Maori Village theme park illustrates the ingenuity of some MÄori. This is a pre-European MÄori village 15 minutes south of Rotorua. This has become a major attraction in New Zealand tourism, winning countless business and tourism awards, including New Zealand's Supreme Tourism Award and Ernst and Young Entrepreneur of the Year Award.

The traditional game of Ki-o-rahi has undergone somewhat of a revival, including restoring and recreating traditional fields:

Weâre trying to get a traditional ki-o-rahi field built in Uawa. Thereâs none left in the country that have carved pou â seven around the outside and one in the middle. The traditional field is an art piece because it has all the carved pou, but itâs still used as a practical setting to play the game, and I donât know of many art pieces like that in the world. I think it would be a real centrepiece for Uawa that people would come and see.[5]

All this contrasts with the fact that MÄori as a whole remain one of the poorer population groups in New Zealand. Despite significant social and economic advances during the twentieth century, MÄori tend to cluster in the lower percentiles in most health and education statistics and in labor-force participation, as well as featuring disproportionately highly in criminal and imprisonment statistics. As with many indigenous cultures from around the world, MÄori suffer both institutional and direct racism.

Notes

- â Douglas G. Sutton (ed.), The Origins of the First New Zealanders. (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1994, ISBN 1869400984).

- â Michael King, The Penguin History of New Zealand (Penguin Books, 2003, ISBN 0143018671).

- â Frederick Edward Maning, Old New Zealand: A Tale of the Good Old Times, and a History of the War in the North against the Chief Heke (1906, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001, ISBN 1402166265).

- â Mick Pendergrast, Fun with Flax: 50 Projects for Beginners (Auckland, Reed Methuen: 1998, ISBN 0790000539).

- â 5.0 5.1 Martin Gibson, "Traditional sports on comeback," The Gisborne Herald (July 27, 2009). Retrieved August 3, 2009.

- â Howard Frederick, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Aotearoa New Zealand 2005 (New Zealand: GEM, 2006).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australians' Ancestries: 2001. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Catalogue Number 2054.0., 2004. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- Brown, Harko. Nga Taonga Takaro: Maori Sports and Games. Raupo, 2008. ISBN 0143009702

- Carlisle, Rodney P. Encyclopedia of Play in Today's Society. Sage Publications, 2009. ISBN 1412966701

- Hiroa, Te Rangi (Buck, Peter). The Coming of the MÄori. Wellington: Whitcombe and Tombs, 1974.

- Irwin, Geoffrey. The Prehistoric Exploration and Colonization of the Pacific. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 0521476518

- King, Michael. The Penguin History of New Zealand. Penguin Books, 2003. ISBN 0143018671

- Maning, Frederick Edward. Old New Zealand: A Tale of the Good Old Times, and a History of the War in the North against the Chief Heke Adamant Media Corporation, 2001 (original 1906). ISBN 1402166265

- Patterson, John. Exploring Maori Values. Dunmore Press, 1992. ISBN 0864691564

- Pendergrast, Mick. Fun with Flax: 50 Projects for Beginners. Auckland: Reed, 1998. ISBN 0790000539.

- Simmons, D. R. Ta Moko, The Art of MÄori Tattoo. Auckland: Reed, 1997. ISBN 0790005689

- Statistics Canada. Ethnic Origin (232), Sex (3) and Single and Multiple Responses (3) for Population, for Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census MetropolitanAreas and Census Agglomerations, 2001 Census - 20% Sample Data. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Cat. No. 97F0010XCB2001001, 2003. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- Statistics New Zealand. Estimated resident population of MÄori ethnic group, at 30 June 1991-2005, selected age groups by sex Wellington: Statistics New Zealand, 2005. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- Sutton, Douglas G. (ed.) The Origins of the First New Zealanders. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1994. ISBN 1869400984

- U.S. Census Bureau. Census 2000 Foreign-Born Profiles (STP-159): Country of Birth: New Zealand Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, 2003.

- Walrond, Carl. MÄori overseas Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, 2005. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

External links

All links retrieved April 29, 2025.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.