Labour Party (UK)

| Labour Party | |

|---|---|

| Leader | Keir Starmer |

| Founded | 1900 |

| Headquarters | 105 Victoria Street London |

| Political Ideology | Social democracy Democratic socialism |

| Political Position | Centre-left |

| International Affiliation | Socialist International |

| European Affiliation | Party of European Socialists |

| European Parliament Group | Party of European Socialists |

| Colours | Red |

| Website | www.labour.org.uk |

| See also | Politics of the UK Political parties |

The Labour Party is a political party in the United Kingdom. Founded at the start of the twentieth century, it has been, since the 1920s, the principal party of the left in Great Britain, which comprises England, Scotland and Wales, but not Northern Ireland, where the Social Democratic and Labour Party occupies a roughly similar position on the political spectrum (although people in Northern Ireland are eligible to join the Labour Party). The party is described as centre-left, bringing together an alliance of social democratic, democratic socialist, and trade unionist outlooks.

Labour surpassed the Liberal Party as the main opposition to the Conservatives in the early 1920s. It has had several spells in government, first as minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931, then as a junior partner in the wartime coalition from 1940-1945, and then as a majority government, under Clement Attlee in 1945-1951 and under Harold Wilson in 1964-1970. Labour was in government again in 1974-1979 under Wilson and then James Callaghan, though with a precarious and declining majority. The Labour Party was more recently in government from 1997 to 2010 under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, during the "New Labour" era.

The party's platform emphasises greater state intervention, social justice and strengthening workers' rights. Labour is a full member of the Party of European Socialists and Progressive Alliance, and holds observer status in the Socialist International.

Party ideology

The Labour Party grew out of the trade union movement and socialist political parties of the nineteenth century, and continues to describe itself as a party of democratic socialism. Labour was the first political party in Great Britain to stand for the representation of the low-paid working class and the working class were known as the Labour Party grassroots and members and voters. Historically within the party, differentiation was made between the social democratic and the socialist wings of the party, the latter often subscribing to a radical socialist, even Marxist, ideology.

Traditionally, the party was in favor of socialist policies such as public ownership of key industries, government intervention in the economy, redistribution of wealth, increased rights for workers and trade unions, and a belief in the welfare state and publicly funded healthcare and education:

The Labour Party is a democratic socialist party. It believes that by the strength of our common endeavour we achieve more than we achieve alone, so as to create for each of us the means to realise our true potential and for all of us a community in which power, wealth and opportunity are in the hands of the many, not the few, where the rights we enjoy reflect the duties we owe, and where we live together, freely, in a spirit of solidarity, tolerance and respect. [1]

Since the mid-1980s, under the leadership of Neil Kinnock, John Smith and Tony Blair the party has moved away from its traditional socialist position towards what is often described as the "Third Way," adopting some free market policies.[2]

This led many observers to describe the Labour Party as social democratic or even neo-liberal rather than democratic socialist.[3] The Labour government under Blair and then Gordon Brown brought in policies such as introducing a minimum wage and increasing the spending on the National Health Service (NHS) and education. It was also credited with reducing the gap between the rich and poor.[4]

Party electoral manifestos have not contained the term socialism since 1992. The new version of Clause IV, though affirming a commitment to democratic socialism,[1] no longer definitely commits the party to public ownership of industry: in its place it advocates "the enterprise of the market and the rigour of competition" along with "high quality public services ... either owned by the public or accountable to them."[1]

Some commentators have argued that traditional social democratic parties across Europe, including the British Labour Party, have been so deeply transformed in recent years that it is no longer possible to describe them ideologically as "social democratic,"[5] and claim that this ideological shift has put new strains on the Labour Party's traditional relationship with the trade unions.[6]

Party constitution and structure

The Labour Party is a membership organization consisting of Constituency Labour Parties, affiliated trade unions, socialist societies, and the Co-operative Party, with which it has an electoral agreement. Members who are elected to parliamentary positions take part in the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) and European Parliamentary Labour Party (EPLP). The party's decision-making bodies on a national level formally include the National Executive Committee (NEC), Labour Party Conference, and National Policy Forum (NPF)–although in practice the Parliamentary leadership has the final say on policy. Questions of internal party democracy have frequently provoked disputes in the party.

For many years Labour held to a policy of uniting Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland by consent, and had not allowed residents of Northern Ireland to apply for membership, instead supporting the nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) which informally takes the Labour whip at the House of Commons.[7] Yet, Labour has a unionist faction in its ranks, many of whom assisted in the foundation in 1995 of the UK Unionist Party led by Robert McCartney. The 2003 Labour Party Conference accepted legal advice that the party could not continue to prohibit residents of the province joining.[8]

Labour is strictly not a political party, but instead a composition of trade unions and various political organizations. Labour defines a difference between the leading Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP), Constituency Labour Parties (CLP), Socialist Societies, Trade Union affiliates and various political parties that choose to affiliate to Labour known as entryist groups, though the Communist Party of Britain has been refused affiliation on occasion. Vladimir Lenin argued that socialist parties should affiliate to Labour to influence the PLP.[9]

History

Founding of the party

The Labour Party's origins lie in the late nineteenth century when it became apparent that there was a need for a political party to represent the interests and needs of the urban proletariat which had increased in numbers, and of working-class males who had recently been given franchise. Some members of the trade union movement became interested in moving into the political field, and after the extensions of the franchise in 1867 and 1885, the Liberal Party endorsed some trade-union sponsored candidates. In addition, several small socialist groups had formed around this time with the intention of linking the movement to political policies. Among these were the Independent Labour Party, the intellectual and largely middle-class Fabian Society, the Social Democratic Federation and the Scottish Labour Party.

In the 1895 General Election the Independent Labour Party put up 28 candidates, but won only 44,325 votes. Keir Hardie, the leader of the party believed that to obtain success in parliamentary elections, it would be necessary to join with other left-wing groups.

Labour Representation Committee

In 1899, a Doncaster member of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, Thomas R. Steels, proposed in his union branch that the Trade Union Congress call a special conference to bring together all the left-wing organizations and form them into a single body which would sponsor Parliamentary candidates. The motion was passed at all stages by the TUC, and this special conference was held at the Memorial Hall, Farringdon Street, London on February 26-27, 1900. The meeting was attended by a broad spectrum of working-class and left-wing organizations; trade unions representing about one third of the membership of the TUC delegates.[10]

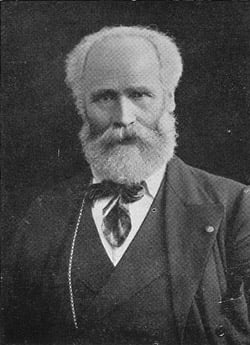

After a debate, the 129 delegates passed Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour."[11] This created an association called the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), meant to coordinate attempts to support MPs—MPs sponsored by trade unions and representing the working-class population.[12] It had no single leader. In the absence of one, the Independent Labour Party nominee Ramsay MacDonald was elected as Secretary. He had the difficult task of keeping the various strands of opinions in the LRC united. The October 1900 "Khaki election" came too soon for the new party to effectively campaign; total expenses for the election only came to £33.[13] Only 15 candidatures were sponsored, but two were successful: Keir Hardie in Merthyr Tydfil and Richard Bell in Derby.[14]

Support for the LRC was boosted by the 1901 Taff Vale Case, a dispute between strikers and a railway company that ended with the union ordered to pay £23,000 damages for a strike. The judgment effectively made strikes illegal since employers could recoup the cost of lost business from the unions. The apparent acquiescence of the Conservative government of Arthur Balfour to industrial and business interests (traditionally the allies of the Liberal Party in opposition to the Conservative's landed interests) intensified support for the LRC against a government that appeared to have little concern for the industrial proletariat and its problems.[14]

In the 1906 election, the LRC won 29 seats—helped by the secret 1903 pact between Ramsay Macdonald and Liberal Chief Whip Herbert Gladstone, which aimed at avoiding Labour/Liberal contests in the interest of removing the Conservatives from office.[14]

In their first meeting after the election, the group's Members of Parliament decided adopt the name "The Labour Party" (February 15, 1906). Keir Hardie, who had taken a leading role in getting the party established, was elected as Chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party (in effect, the Leader), although only by one vote over David Shackleton after several ballots. In the party's early years, the Independent Labour Party (ILP) provided much of its activist base as the party did not have an individual membership until 1918 and operated as a conglomerate of affiliated bodies until that date. The Fabian Society provided much of the intellectual stimulus for the party. One of the first acts of the new Liberal government was to reverse the Taff Vale judgment.[14]

Early years, and the rise of the Labour Party

The December 1910 General Election saw 42 Labour MPs elected to the House of Commons.

This was a significant victory since a year before the election the House of Lords had passed the Osborne judgment which ruled that Trades Unions in the United Kingdom could no longer donate money to fund the election campaigns and wages of Labour MPs. The governing Liberals were unwilling to repeal this judicial decision with primary legislation. The height of Liberal compromise was to introduce a wage for Members of Parliament, to remove the need to involve the Trade Unions. By 1913, faced with the opposition of the largest Trade Unions, the Liberal government passed the Trade Disputes Act to once more allow Trade Unions to fund Labour MPs.

During the First World War the Labour Party split between supporters and opponents of the conflict and opposition within the party to the war grew as time went on. Ramsay MacDonald, a notable anti-war campaigner, resigned as leader of the Parliamentary Labour Party and Arthur Henderson became the main figure of authority within the Party and was soon accepted into H. H. Asquith's War Cabinet, becoming the first Labour Party member to serve in government.

Despite mainstream Labour Party's support for the Coalition, the Independent Labour Party was instrumental in opposing mobilization through organizations such as the Non-Conscription Fellowship and a Labour Party affiliate, the British Socialist Party, organized a number of unofficial strikes.

Arthur Henderson resigned from the Cabinet in 1917 amidst calls for Party unity, being replaced by George Barnes. The growth in Labour's local activist base and organization was reflected in the elections following the War, with the co-operative movement now providing its own resources to the Co-operative Party after the armistice. The Co-operative Party later reached an electoral agreement with the Labour Party.

Following the war, the Liberal Party went into rapid decline. With the party suffering a catastrophic split between supporters of leader David Lloyd George and former leader H. H. Asquith. This allowed the Labour Party to co-opt much of the Liberals' support.

With the Liberals in disarray, Labour won 142 seats at the 1922 General Election making it the second largest political group in the British House of Commons and the official opposition to the Conservative Government. After the election, the now rehabilitated Ramsay MacDonald was voted the first official leader of the Labour Party.

First Labour governments

MacDonald government (1924)

The 1923 general election was fought on the Conservatives' protectionist proposals; although they got the most votes and remained the largest party, they lost their majority in parliament, requiring a government supporting free trade to be formed. So with the acquiescence of Asquith's Liberals, Ramsay MacDonald became Prime Minister in January 1924 and formed the first ever Labour government, despite Labour only having 191 MPs (less than a third of the House of Commons).

Because the government had to rely on the support of the Liberals, it was unable to get any socialist legislation passed by the House of Commons. The only significant measure was the Wheatley Housing Act which began a building programme of 500,000 homes for rent to working-class families.

The government collapsed after only nine months when the Liberals voted for a Select Committee inquiry into the Campbell Case, a vote which MacDonald had declared to be a vote of confidence. The ensuing general election saw the publication, four days before polling day, of the notorious Zinoviev letter, which implicated Labour in a plot for a Communist revolution in Britain, and the Conservatives were returned to power, although Labour increased its vote from 30.7 percent of the popular vote to a third of the popular vote; most of the Conservative gains were at the expense of the Liberals. The Zinoviev letter is now generally believed to have been a forgery.[15]

In opposition, Ramsay MacDonald continued with his policy of presenting the Labour Party as a moderate force in politics. During the General Strike of 1926 he opposed strike action arguing that the best way to achieve social reforms was through the ballot box.

MacDonald government (1929-1931)

At the 1929 general election the Labour Party for the first time became the largest grouping in the House of Commons with 287 seats, and 37.1 percent of the popular vote (actually slightly less than the Conservatives). However, MacDonald was still reliant on Liberal support to form a minority government.

The government however, soon found itself engulfed in crisis; The Wall Street Crash of 1929 and eventual Great Depression occurred soon after the government came to power, and the crisis hit Britain hard. By the end of 1930, the unemployment rate had doubled to over 2.5 million.[16]

The government had no effective answers to the crisis. By the summer of 1931, a dispute over whether to introduce large cuts to public spending split the government. With the economic situation worsening, MacDonald agreed to form a "National Government" with the Conservatives and the Liberals.

On August 24, 1931, MacDonald submitted the resignation of his ministers and led a small number of his senior colleagues in forming the National Government with the other parties. This move caused great anger within the Labour Party and MacDonald and his supporters were then expelled from the Labour Party and formed the National Labour Party. The remaining Labour Party, now led by Arthur Henderson, and a few Liberals went into opposition.

Soon after this, a General Election was called. The 1931 election resulted in a landslide victory for the National Government, and was a disaster for the Labour Party which won only 52 seats, 225 fewer than in 1929.

Opposition during the 1930s

Arthur Henderson, who had been elected in 1931 as Labour leader to succeed MacDonald, lost his seat in the 1931 General Election. The only former Labour cabinet member who survived the landslide was the pacifist George Lansbury, who accordingly became party leader.

The party experienced a further split in 1932 when the Independent Labour Party, which for some years had been increasingly at odds with the Labour leadership, opted to disaffiliate from the Labour Party. The ILP embarked on a long drawn out decline.

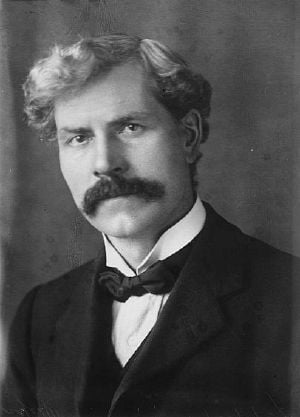

Lansbury resigned as leader in 1935 after public disagreements over foreign policy. He was replaced as leader by his deputy, Clement Attlee. The party experienced a revival at the 1935 General Election, winning a similar number of votes to those attained in 1929 and actually, at 38 percent of the popular vote, the highest percentage that Labour had ever achieved, securing 154 seats.

With the rising threat from Nazi Germany in the 1930s, the Labour Party gradually abandoned its earlier pacifist stance, and came out in favor of rearmament. This shift largely came about due to the efforts of Ernest Bevin and Hugh Dalton who by 1937 also persuaded the party to oppose Neville Chamberlain's policy of appeasement.[16]

Wartime coalition

The party was brought back into government in 1940 as part of a wartime coalition government: When Neville Chamberlain resigned as Prime Minister after the defeat in Norway in spring 1940, and incoming Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided that it was important to bring the other main parties into the government and have a Wartime Coalition similar to that in the First World War. Clement Attlee became Lord Privy Seal and a member of the War cabinet, and was effectively (and eventually formally) Deputy Prime Minister for the remainder of the duration of the War in Europe.

A number of other senior Labour figures took up senior positions: the trade union leader Ernest Bevin as Minister of Labour directed Britain's wartime economy and allocation of manpower; the veteran Labour statesman Herbert Morrison became Home Secretary; Hugh Dalton was Minister of Economic Warfare and later President of the Board of Trade; and A. V. Alexander resumed the role of First Lord of the Admiralty he had held in the previous Labour government. The party generally performed well in government, and its experience there may have been partly responsible for its post-war success.

Post-War victory under Attlee

With the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, Labour resolved not to repeat the Liberals' error of 1918, and withdrew from the government to contest the 1945 general election (July 5) in opposition to Churchill's Conservatives. Surprising many observers, Labour won a landslide victory, winning just under 50 percent of the vote with a majority of 145 seats.

Clement Attlee's government proved to be one of the most radical British governments of the twentieth century. It presided over a policy of selective nationalization of major industries and utilities, including the Bank of England, coal mining, the steel industry, electricity, gas, telephones, and inland transport (including the railways, road haulage and canals). It developed the "cradle to grave" welfare state conceived by the Liberal economist William Beveridge. To this day, the party still considers the creation in 1948 of Britain's publicly funded National Health Service under health minister Aneurin Bevan its proudest achievement.

Attlee's government also began the process of dismantling the British Empire when it granted independence to India in 1947. This was followed by Burma (Myanmar) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) the following year.

With the onset of the Cold War, at a secret meeting in January 1947, Attlee, and six cabinet ministers including foreign minister Ernest Bevin, secretly decided to proceed with the development of Britain's nuclear deterrent,[16] in opposition to the pacifist and anti-nuclear stances of a large element inside the Labour Party.

Labour won the 1950 general election but with a much reduced majority of five seats. Soon after the 1950 election, things started to go badly for the Labour government. Defense became one of the divisive issues for Labour itself, especially defense spending (which reached 14 percent of GDP in 1951 during the Korean War).[17] These costs put enormous strain on public finances, forcing savings to be found elsewhere. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Hugh Gaitskell introduced prescription charges for NHS prescriptions, causing Bevan, along with Harold Wilson (President of the Board of Trade) to resign over the dilution of the principle of free treatment.

Soon after this, another election was called. Labour narrowly lost the October 1951 election to the Conservatives, despite their receiving a larger share of the popular vote and, in fact, their highest vote ever numerically.

Most of the changes introduced by the 1945-1951 Labour government however were accepted by the Conservatives and became part of the "post war consensus," which lasted until the 1970s.

The "Thirteen Wasted Years"

Following their defeat in 1951 the party underwent a long period in opposition lasting 13 years. The party suffered an ideological split during the 1950s, and the postwar economic recovery meant that the public was broadly contented with the Conservative governments of the time. Attlee remained as leader until his retirement in 1955.

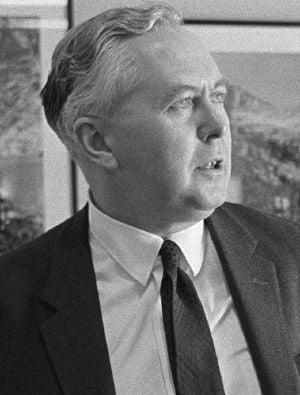

His replacement Hugh Gaitskell struggled with internal divisions within the party in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and Labour lost the 1959 general election. Gaitskell's sudden death in 1963 made way for Harold Wilson to lead the party.

The 1960s and 1970s

Wilson government (1964-1970)

A downturn in the economy, along with a series of scandals in the early 1960s (the most notorious being the Profumo affair), engulfed the Conservative government by 1963. The Labour party returned to government with a razor-thin four-seat majority under Wilson in the 1964 election, and increased their majority to 96 in 1966 election.

Events derailed the wave of optimism which swept Labour to power in 1964. Wilson's government inherited a large trade deficit, which led to a currency crisis and an ultimately doomed attempt to stave off devaluation of the pound.

Despite the crisis, Wilson's government was responsible for a number of social and educational reforms such as legalization of abortion and homosexuality, and the abolition of the death penalty for murder. The 1960s Labour government also expanded comprehensive education and created the Open University.

Labour unexpectedly lost the 1970 general election to the Conservatives under Edward Heath. Heath's government however soon ran into trouble over Northern Ireland and a dispute with miners in 1973 which led to the "three-day week."

The 1970s proved to be a very difficult time to be in government for both the Conservatives and Labour due to the 1973 oil crisis which caused high inflation and a global recession.

Labour returned to power again under Wilson a few weeks after the February 1974 general election, forming a minority government with Ulster Unionist support. The Conservatives were unable to form a government as they had fewer seats, even though they had received more votes. It was the first General Election since 1924 in which both main parties received less than 40 percent of the popular vote, and was the first of six successive General Elections in which Labour failed to reach 40 percent of the popular vote. In a bid for Labour to gain a majority, a second election was soon called for October 1974 in which Labour, still with Harold Wilson as leader, scraped a majority of three, gaining just 18 seats and taking their total to 319.

Labour in power 1974-1979

In government, the Labour Party's internal splits over Britain's membership of the European Economic Community (EEC) which Britain had entered under Edward Heath in 1972, led to a national referendum on the issue in 1975, in which two thirds of the public supported continued membership.

The Labour Government struggled for much of its time in office with serious economic problems and a precarious and declining majority in the commons. Fear of advances by the nationalist parties, particularly in Scotland, led to the suppression of a report from Scottish Office economist Gavin McCrone which suggested that an independent Scotland would be 'chronically in surplus' and to secret collusion with Margaret Thatcher's Conservatives. Harold Wilson unexpectedly resigned as prime minister in 1976. He was replaced by James Callaghan.

The Wilson and Callaghan governments were hampered by their lack of a workable majority in the commons. At the October 1974 election, Labour won a majority of only three seats. Several by election losses and defections to the breakaway Scottish Labour Party meant that by 1977, Callaghan was heading a minority government, and was forced to do deals with other parties to survive. An arrangement was negotiated in 1977 with the Liberal leader David Steel known as the Lib-Lab pact, but this ended after one year. After this, deals were made with various small parties, including the Scottish National Party and the Welsh nationalist Plaid Cymru, which prolonged the life of the government slightly longer.

The nationalist parties demanded devolution to their respective countries in return for their support for the government. When referendums for Scottish and Welsh devolution were held in March 1979, the Welsh referendum was rejected outright, and the Scottish referendum had a narrow majority in favor but did not reach the threshold of 40 percent support of the electorate, a requirement of the legislation. When the Labour Government refused to push ahead with setting up the Scottish Assembly, the SNP withdrew its support for the government, causing the government to collapse on a vote of no confidence.

The Wilson and Callaghan governments in the 1970s tried to control inflation (which had reached 26.9 percent in 1975) by instituting a policy of wage restraint. This policy was initially fairly successful at controlling inflation, which had been reduced to 7.4 percent by 1978.[14] However, it led to increasingly strained relations between the government and the trade unions.

Callaghan had been widely expected to call a general election in the autumn of 1978, when most opinion polls showed Labour to have a narrow lead.[14] However instead, he decided to extend the wage restraint policy for another year in the hope that the economy would be in a better shape in time for a 1979 election. This proved to be a big mistake.

During the winter of 1978-1979 there were widespread strikes in favor of higher pay rises which caused significant disruption to everyday life. The strikes affected lorry drivers, railway workers, car workers and local government and hospital workers. These came to be dubbed as the "Winter of Discontent."

The strikes made Callaghan's government unpopular. After the withdrawal of SNP support for the government, the Conservatives put down a vote of no confidence, which was held and passed by one vote on March 28, 1979, forcing a general election.

In the 1979 general election, Labour suffered electoral defeat to the Conservatives led by Margaret Thatcher. The numbers voting Labour hardly changed between February 1974 and 1979, but in 1979 the Conservative Party achieved big increases in support in the Midlands and South of England, mainly from the ailing Liberals, and benefited from a surge in turnout.

The 'Wilderness Years' (1979-1997)

Following their defeat at the 1979 election, the Labour Party underwent a period of bitter internal rivalry in the Labour Party which had become increasingly divided between the ever more dominant left-wingers under Michael Foot and Tony Benn (whose supporters dominated the party organization at the grassroots level), and the right under Denis Healey.

The election of Michael Foot as leader in 1980, dismayed many on the right of the party, who believed that Labour was becoming too left-wing. In 1981 a group of four former cabinet ministers from the right and center of the Labour Party (Shirley Williams, William Rodgers, Roy Jenkins, and David Owen) issued the "Limehouse Declaration" and formed the breakaway Social Democratic Party.

Margaret Thatcher's government was initially deeply unpopular due to high unemployment and inflation but the success of the Falklands War in 1982, her success in controlling inflation and the right to buy revived her popularity, while the formation of the SDP split the opposition vote. The Labour Party was defeated by a landslide in the 1983 general election winning only 27.6 percent of the vote, their lowest share since 1918. Labour won only half-a-million votes more than the SDP-Liberal Alliance which had attracted the votes of many moderate Labour supporters.

Michael Foot resigned as leader and was replaced by Neil Kinnock, who progressively moved the party towards the center. Labour improved its performance at the 1987 general election, gaining 20 seats reducing the Conservative majority to 102 from 143 in 1983, despite a sharp rise in turnout.

Neil Kinnock was seen as too right-wing for much of the Labour Left—especially the Militant Tendency that Kinnock later forced them out of the party; they would later become the Socialist Party of England and Wales.

Margaret Thatcher was replaced as prime minister by John Major in 1990. By the time of the 1992 general election, the economy was in recession and, despite the personal unpopularity of Neil Kinnock, Labour looked as if it could win. The party had dropped its policy of Unilateral Nuclear Disarmament, and had tried to present itself as a credible government-in-waiting. Most opinion polls showed the party to have a slight lead over the Conservatives, although rarely sufficient for a majority. The Conservatives were returned to power but with a much reduced majority of 20. Although Labour's support was comparable to the February and October 1974 and May 1979 General Elections, the overall turnout was much larger.

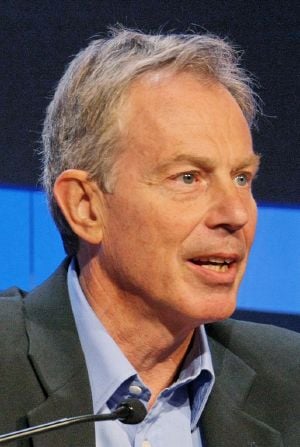

Kinnock resigned as leader and was replaced by John Smith. Soon after the 1992 election, the Conservative government ran into trouble, when on Black Wednesday it was forced to leave the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. After this, Labour moved ahead in the opinion polls as the Conservatives declined in popularity. John Smith's sudden death from a heart attack in May 1994 made way for Tony Blair to lead the Party.

New Labour

Tony Blair moved the party further to the right, adopting policies which broke with Labour's socialist heritage at the 1995 mini-conference in a strategy to increase the party's appeal to "middle England."

"New Labour" was first termed as an alternative branding for the Labour Party, dating from a conference slogan first used by the Labour Party in 1994 which was later seen in a draft manifesto published by the party in 1996, called New Labour, New Life For Britain. The rise of the name coincided with a rightwards shift of the British political spectrum; for Labour, this was a continuation of the trend that had begun under the leadership of Neil Kinnock. "New Labour" as a name has no official status but remains in common use to distinguish modernizers from those holding to more traditional positions who normally are referred to as "Old Labour." New Labour has been used a derogative term by some to separate the "Thatcherite" policies adopted by Tony Blair and Gordon Brown to that of Old Labour and the old Clause 4.

New Labour's apparent abandoning of working class supporters has resulted, some argue, in the Campaign for a New Workers' Party, the Respect Coalition, the rise in the Scottish National Party and the British National Party, revival of the Conservative Party, questioning of capitalism and trade union activity that has not been seen since the 1980s.

In government

With the unpopularity of John Major's government, the Labour party won the 1997 election with a landslide majority of 179.

Among the early acts of Tony Blair's government were the establishment of the National minimum wage, the devolution of power to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and the re-creation of a city-wide government body for London; the Greater London Authority.

Labour went on to win the 2001 election with a similar majority to 1997. Tony Blair controversially allied himself with President George W. Bush in supporting the Iraq War, which lost his government much support.[18]

At the 2005 election, Labour was returned to power with a much reduced majority.

The party lost power in Scotland after losing the 2007 Scottish Parliament election. In the same year, Tony Blair stood down as prime minister and was replaced by Gordon Brown. Although the party experienced a brief rise in the polls, the party's popularity soon slumped to its lowest level since under Michael Foot. During May 2008, Labour suffered heavy defeats in the London mayoral election, local elections and the Crewe and Nantwich by-election, culminating in the party registering its worst ever opinion poll result since records began in 1943, of 23 percent.[19]

Finance proved a major problem for the Labour Party at the beginning of the twenty-first century. A "cash for peerages" scandal under Tony Blair resulted in the drying up of many major sources of donations. Declining party membership, partially due to the reduction of activists' influence upon policymaking under the reforms of Neil Kinnock and Tony Blair, has also contributed to financial woes.

Gordon Brown's Labour government suffered its first significant defeat in the House Of Lords on October 15, 2008, when the Lords rejected proposals to allow police to hold terror suspects for 42 days without charge. Gordon Brown was accused of a "tax bombshell" by opposition leader David Cameron, who argued that the "tax cut" of VAT by 2.5 percent and the overall tax cut package was funded by debt which would lead to future tax increases.[20]

In the 2010 general election, Labour with 29.0 percent of the vote won the second largest number of seats (258). The Conservatives with 36.5 percent of the vote won the largest number of seats (307), but no party had an overall majority, meaning that Labour could still remain in power if they managed to form a coalition with more than one other smaller party to gain an overall majority; anything less would result in a minority government. On 10 May 2010, after talks to form a coalition with the Liberal Democrats broke down, Brown announced his intention to stand down as Leader before the Labour Party Conference, and a day later resigned as both Prime Minister and party leader.

In opposition

Harriet Harman became the Leader of the Opposition and acting Leader of the Labour Party following the resignation of Gordon Brown, pending a leadership election subsequently won by Ed Miliband. Miliband emphasised "responsible capitalism" and greater state intervention to change the balance of the economy away from financial services. Tackling vested interests[21] and opening up closed circles in British society were themes he returned to a number of times. Miliband also argued for greater regulation of banks and energy companies.[22]

The Parliamentary Labour Party voted to abolish Shadow Cabinet elections in 2011,[23] ratified by the National Executive Committee and Party Conference.

On March 1, 2014, at a special conference the party reformed internal Labour election procedures, including replacing the electoral college system for selecting new leaders with a "one member, one vote" system following the recommendation of a review by former general-secretary Ray Collins. Mass membership would be encouraged by allowing "registered supporters" to join at a low cost, as well as full membership. Members from the trade unions would also have to explicitly "opt in" rather than "opt out" of paying a political levy to Labour.[24]

In September 2014, Shadow Chancellor Ed Balls outlined his plans to cut the government's current account deficit, and the party carried these plans into the 2015 general election. Whereas Conservatives campaigned for a surplus on all government spending, including investment, by 2018-19, Labour stated it would balance the budget, excluding investment, by 2020.[25]

The 2015 general election unexpectedly resulted in a net loss of seats, with Labour representation falling to 232 seats in the House of Commons.[26] The party lost 40 of its 41 seats in Scotland in the face of record swings to the Scottish National Party. Though Labour gained more than 20 seats in England and Wales, mostly from the Liberal Democrats but also from the Conservative Party, it lost more seats to the Conservatives, for net losses overall.[27]

The day after May 7, 2015 election, Miliband resigned as party leader. Harriet Harman again became acting leader. The Labour Party held a leadership election, in which Jeremy Corbyn, then a member of the Socialist Campaign Group, was elected leader by a landslide. [28]

On April 18, 2017, Prime Minister Theresa May announced she would seek an unexpected snap election on June 8, 2017. Corbyn said he welcomed May's proposal and said his party would support the government's move in the parliamentary vote announced for 19 April.[29] Some of the opinion polls had shown a 20-point Conservative lead over Labour before the election was called, but this lead had narrowed by the day of the general election, which resulted in a hung parliament. Despite remaining in opposition for its third election in a row, Labour at 40.0 percent won its greatest share of the vote since 2001, made a net gain of 30 seats to reach 262 total MPs, and, with a swing of 9.6 percent, achieved the biggest percentage-point increase in its vote share in a single general election since 1945.[30]

Following Labour's heavy defeat in the 2019 general election, Jeremy Corbyn announced that he would stand down as Leader of the Labour Party. Keir Starmer announced his candidacy in the ensuing leadership election on January 4, 2020, winning multiple endorsements from MPs as well as from the trade union Unison.[31] He went on to win the leadership contest on April 4, 2020, beating rivals Rebecca Long-Bailey and Lisa Nandy, and therefore also became Leader of the Opposition.[32] In his acceptance speech, he said would refrain from "scoring party political points" and that he planned to "engage constructively with the government", having become Opposition Leader amid the COVID-19 pandemic.[33] He appointed his Shadow Cabinet the following day, which included former leader Ed Miliband, as well as both of the candidates he defeated in the leadership contest. He also appointed Anneliese Dodds as Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, making her the first woman to serve in that position in either a ministerial or shadow ministerial position.[34]

In the 2023 United Kingdom local elections, Labour saw a net gain of 536 councillors and 22 councils, becoming the largest party of local government for the first time since 2002.[35]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Labour Party Rule Book 2013 Labour.org.uk. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Helene Mulholland, Labour will continue to be pro-business, says Ed Miliband The Guardian (April 7, 2011). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Stuart Hall, New Labour has picked up where Thatcherism left off The Guardian (August 6, 2003). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Matthew Weaver, Guardian Unlimited, Wealth Gap Narrows faster in UK The Guardian (October 21, 2008). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Ashley Lavelle, The Death of Social Democracy: Political Consequences for the 21st Century (Routledge, 2008, ISBN 978-0754670148).

- ↑ Gary Daniels and John McIlroy (eds.), Trade Unions in a Neoliberal World: British Trade Unions under New Labour (Routledge, 2009, ISBN 978-0415603096).

- ↑ Antony Alcock, The Unloved, Unwanted Garrison Understanding Ulster (Ulster Society Publications, 1997). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Labour NI ban overturned BBC News (October 1, 2003). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Tony Cliff and Donny Gluckstein, The Labour Party: A Marxist History (Bookmarks, 1988, ISBN 978-0906224458).

- ↑ Jim Mortimer, The formation of the labour party - Lessons for today Socialist History Society, 2000. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ David Shackelton Spartacus Educational. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Ralph Miliband, Parliamentary Socialism (Merlin Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0850361353).

- ↑ Tony Wright and Matt Carter, People's Party: The History of the Labour Party (Thames & Hudson Ltd, 1997, ISBN 978-0500279564).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Andrew Thorpe, A History Of The British Labour Party (Palgrave, 2001, ISBN 978-0333560808).

- ↑ Richard Norton-Taylor, Zinoviev letter was dirty trick by MI6 The Guardian (February 3, 1999). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 A.J. Davies, To Build A New Jerusalem: The British Labour Party from Keir Hardie to Tony Blair (Abacus, 1996, ISBN 0349108099).

- ↑ Sir George Clark, Illustrated History Of Great Britain (Octopus Books, 1982, ISBN 978-0706416664).

- ↑ European Opposition To Iraq War Grows DW (January 13, 2003). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Brown hit by worst party rating Reuters (May 9, 2008). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Andrew Grice, Cameron predicts £1,500 'tax bombshell' The Independent (November 18, 2008). Retrieved July 2023.

- ↑ Ed Miliband: Surcharge culture is fleecing customers BBC News (January 19, 2012). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Ed Miliband's Banking Reform Speech: The Full Details New Statesman (January 16, 2014). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Barry Neild, Labour MPs vote to abolish shadow cabinet elections The Guardian (July 6, 2011). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Andrew Grice, Tony Blair backs Ed Miliband's internal Labour reforms The Independent (February 28, 2014). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Robert Preston, Is Osborne right that a smaller state means a richer UK? BBC News (September 29, 2014). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Sophie McIntyre, How many seats did Labour win? The Independent (May 7, 2015). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Labour election results: Ed Miliband resigns as leader BBC News (May 8, 2015). Retrieved July 16, 2023

- ↑ Rowena Mason, Labour leadership: Jeremy Corbyn elected with huge mandate The Guardian (September 12, 2015). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Jon Stone, Jeremy Corbyn welcomes Theresa May's announcement of an early election The Independent (April 18, 2017). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Harriet Agerholm and Louis Dore, Jeremy Corbyn increased Labour's vote share more than any of the party's leaders since 1945 The Independent (June 9, 2017). Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ↑ Keir Starmer enters Labour leadership contest BBC News (January 4, 2020). Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- ↑ Keir Starmer Elected as new Labour leader BBC News (April 4, 2020). Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- ↑ Nick Duffy, Sir Keir Starmer statement in full: New Labour leader vows to 'engage constructively' with government on coronavirus iNews (July 13, 2020). Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- ↑ Ed Miliband returns to Labour top team BBC News (April 6, 2020). Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- ↑ Jennifer Scott, Faye Brown, and Alexandra Rogers, Local elections 2023: Labour overtakes Conservatives as largest party of local government Sky News (May 6, 2023). Retrieved July 15, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Clark, Sir George. Illustrated History Of Great Britain. Octopus Books, 1982. ISBN 978-0706416664

- Cliff, Tony, and Donny Gluckstein. The Labour Party: A Marxist History. Bookmarks, 1988. ISBN 978-0906224458

- Daniels, Gary, and John McIlroy (eds.). Trade Unions in a Neoliberal World: British Trade Unions under New Labour. Routledge, 2009. ISBN 978-0415603096

- Davies, A.J, To Build A New Jerusalem. London: Michael Joseph, 1992. ISBN 0349108099

- Foote, Geoffrey. The Labour Party's Political Thought: A History. Dover, NH: Croom Helm, 1985. ISBN 978-0709910756

- Francis, Martin. Ideas and Policies under Labour 1945-51. Manchester University Press, 1997. ISBN 0719048338

- Howell, David. British Social Democracy. Croom Helm, 1976. ISBN 978-0856641244

- Howell, David. MacDonald's Party. Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0198203049

- Lavelle, Ashley. The Death of Social Democracy: Political Consequences for the 21st Century. Routledge, 2008. ISBN 978-0754670148

- Miliband, Ralph. Parliamentary Socialism. Merlin Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0850361353

- Morgan, Kenneth O. Labour in Power, 1945-51. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0192158659

- Morgan, Kenneth O. Labour People: Leaders and Lieutenants, Hardie to Kinnock. Faber and Faber, 2011. ISBN 978-0571259618

- Pelling, Henry, and Alastair J. Reid. A Short History of the Labour Party. Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. ISBN 1403993130

- Pilger, John. Freedom Next time. Bantam Press, 2006. ISBN 0593055527

- Pimlott Ben. Labour and the Left in the 1930s. Cambridge University Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0521214483

- Plant, Raymond, Matt Beech, and Kevin Hickson. The Struggle for Labour's Soul: Understanding Labour's political thought since 1945. Routledge, 2004. ISBN 978-0415312844

- Ponting, Clive. Breach of Promise: Labour in power, 1964-1970. H. Hamilton, 1989. ISBN 978-0241126837

- Rosen, Greg. Dictionary of Labour Biography. Politicos Publishing, 2001. ISBN 1902301188

- Rosen, Greg. Old Labour to New. Politicos Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1842750453

- Shaw, Eric. The Labour Party since 1979: Crisis and Transformation. Routledge, 1994. ISBN 978-0415056151

- Thorpe, Andrew. A History of the British Labour Party. Palgrave Macmillan, 2001. ISBN 978-0333560808

- Whitehead, Phillip. The Writing on the Wall. Michael Joseph, 1985. ISBN 978-0718128074

- Wintour, Patrick, and Colin Hughes. Labour Rebuilt: The New Model Party. Fourth Estate, 1990. ISBN 978-1872180700

- Wright, Tony, and Matt Carter. People's Party: The History of the Labour Party. Thames & Hudson Ltd, 1997. ISBN 978-0500279564

External links

All links retrieved March 7, 2025.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.