Humayun

| Birth name: | Nasiruddin Humayun |

| Family name: | Timurid |

| Title: | Emperor of Mughal Empire |

| Birth: | March 6, 1508 |

| Place of birth: | Kabul |

| Death: | February 22, 1556 |

| Place of death: | Delhi |

| Burial: | Humayun's Tomb |

| Succeeded by: | Akbar |

| Marriage: |

Hamida Banu Begum |

| Children: |

Akbar, son |

Nasiruddin Humayun (Persian: ÙصÙراÙدÙÙ Ù٠اÙÙÙ) (March 6, 1508 â February 22, 1556), the second Mughal Emperor, ruled modern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and parts of northern India from 1530â1540 and again from 1555â1556. Like his father, Babur, he lost his kingdom early, but with Persian aid, he eventually regained an even larger one.

He succeeded his father in India in 1530, while his half-brother Kamran Mirza, who became a rather bitter rival, obtained the sovereignty of Kabul and Lahore, the more northern parts of their father's empire. He originally ascended the throne at the age of 22 proving somewhat inexperienced when he came to power.

Humayun lost his Indian territories to the Afghan Sultan, Sher Shah Suri, and regained them, only with Persian aid, ten years later. Humayun's return from Persia, accompanied by a large retinue of Persian noblemen, signaled an important change in Mughal Court culture, as the Central Asian origins of the dynasty became largely overshadowed by the influences of Persian art, architecture, language and literature. Subsequently, in a relatively short time, Humayun expanded the Empire further, leaving a substantial legacy for his son, Akbar the Great (Akbar-e-Azam).

Background

Babur's decision to divide the territories of his empire between two of his sons marked a departure from the usual practice in India, but it had been a common Central Asian practice since the time of Genghis Khan. Unlike most European Monarchies which practiced primogeniture, the Timurids, following Genghis Khan's example, refused to leave an entire kingdom to the eldest son. Although under that system only a Chingissid could claim sovereignty and khanal authority, any male Chinggisid within a given sub-branch (such as the Timurids) had an equal right to the throne.[1]. While Genghis Khan's Empire had been peacefully divided between his sons upon his death, almost every Chinggisid succession since had resulted in fratricide.[2]

Timur himself had divided his territories between Pir Muhammad, Miran Shah, Khalil Sultan and Shah Rukh, which resulted in inter-family warfare.[1] Upon Babur's death, Humayun's territories proved the least secure. Babur had ruled only four years; the umarah (nobles) divided on whether Humayun represented the rightful ruler. Indeed earlier, when Babur had become ill, some of the nobles had tried to install Humayun's uncle, Mahdi Khwaja, as ruler. Although that attempt failed, it offered a sign of problems to come.[3]

Personal traits

Humayun's sister, Gulbadan Begum, portrayed him in his biography, the "HumÄyÅ«n-nÄma," as extraordinarily lenient, constantly forgiving acts deliberately aimed at angering him. In one instance the biography records his youngest brother Hindal killed Humayun's most trusted advisor, an old Sheikh, and then marched an army out of Agra. Humayun, rather than seek retribution, went straight to his mother's home where Gulbadan Begum and other women gathered, swearing on the Qur'an that he would bear no grudge against his younger brother, and insisted he return home. His many documented acts of mercy may have stemmed largely from weakness, but he does seem to have been a gentle and humane man by the standards of the day.

He had deeply held superstitious, displaying fascination with Astrology and the Occult. Upon his accession as Padishah (Emperor), he began to re-organize the administration upon mystically determined principles. He divided the public offices into four distinct groups, for the four elements. The department of Earth held charge of Agriculture and the agricultural sciences; Fire, the Military; Water, the department of the Canals and waterways; and Air seemed to have responsibility for everything else. He planned his daily routine, and his wardrobe, in accordance with the movements of the planets. He refused to enter a house with his left foot going forward, and if anyone else did they would be told to leave and re-enter.

His servant, Jauhar, records in the Tadhkirat al-Waqiat that he had been reported to shoot arrows to the sky marked with either his own name, or that of the Shah of Persia and, depending on how they landed, interpreted that as an indication of which of them would grow more powerful. He drank heavily, consuming Opium pellets, after which he recited poetry. He disdained warfare; after winning a battle would spend months at a time indulging himself within the walls of a captured city even as a larger war raged outside.

His early reign

Upon his succession to the throne, Humayun had two major rivals interested in acquiring his landsâSultan Bahadur of Gujarat to the south west and Sher Shah Suri (Sher Khan) currently settled along the river Ganges in Bihar to the east.

During the first five years of Humayun's reign, those two rulers quietly extended their rule, although Sultan Bahadur faced pressure in the east from sporadic conflicts with the Portuguese. While the Mughals had acquired firearms via the Ottoman Empire, Bahadur's Gujurat had acquired them through a series of contracts drawn up with the Portuguese, allowing the Portuguese to establish a strategic foothold in north western India.[4]

Humayun became aware that the Sultan of Gujarat planned an assault on the Mughal territories with Portuguese aid. Showing an unusual resolve, Humayun gathered an army and marched on Bahadur. His assault proved spectacular and within a month he had captured the forts of Mandu and Champaner. Instead of pressing his attack and going after the enemy, Humayun ceased the campaign and began to enjoy life in his new forts. Bahadur, meanwhile, escaped and took up refuge with the Portuguese.[5]

Sher Shah Suri

Shortly after Humayun had marched on Gujarat, Sher Shah saw an opportunity to wrest control of Agra from the Mughals. He began to gather his army together hoping for a rapid and decisive siege of the Mughal capital. Upon hearing that alarming news, Humayun quickly marched his troops back to Agra allowing Bahadur to easily regain control of the territories Humayun had recently taken. A few months later Bahadur diedâkilled when a botched plan to kidnap the Portuguese viceroy ended in a fire-fight which the Sultan lost.

While Humayun succeeded in protecting Agra from Sher Shah, the second city of the Empire, Gaur the capital of the vilayat of Bengal, had been sacked. Humayun's troops had been delayed while trying to take Chunar, a fort occupied by Sher Shah's son, to protect his troops from an attack from the rear. The stores of grain at Gaur, the largest in the empire, had been emptied and Humayun arrived to see corpses littering the roads.[6] With the vast wealth of Bengal depleted and brought East, Sher Shah built a substantial war chest. [4]

Sher Shah withdrew to the east, but Humayun held back: instead he "shut himself up for a considerable time in his Harem, and indulged himself in every kind of luxury."[6] Hindal, Humayun's 19-year-old brother, had agreed to aid him in that battle, protecting the rear from attack but abandoned his position, withdrawing to Agra where he decreed himself acting emperor. When Humayun sent the grand Mufti, Sheikh Buhlul, to reason with him, he executed the Sheikh. Further provoking the rebellion, Hindal ordered that the Khutba or sermon in the main mosque at Agra be read in his name, a sign of assumption of sovereignty.[5] When Hindal withdrew from protecting the rear of Humayun's troops, Sher Shah's troop quickly reclaimed those positions, leaving Humayun surrounded.[7]

Humayun's other brother, Kamran, marched from his territories in the Punjab, ostensibly to aid Humayun. His return home had treacherous motives as he intended to stake a claim for Humayun's apparently collapsing empire. He brokered a deal with Hindal which provided that his brother would cease all acts of disloyalty in return for a share in the new empire which Kamran would create once he had deposed Humayun.[7]

Sher Shah met Humayun in battle on the banks of the Ganges, near Benares, in Chausa. That became an entrenched battle in which both sides dug themselves into positions. The major part of the Mughal army, the artillery, became immobile. Humayun decided to engage in diplomacy using Muhammad Aziz as ambassador. Humayun agreed to allow Sher Shah to rule over Bengal and Bihar, but only as provinces granted to him by Humayun as Emperor; that fell short of outright sovereignty for Sher Shah. The two rulers struck a bargain to save face: Humayun's troops would charge those of Sher Shah whose forces then retreat in feigned fear. Thus honor would, supposedly, be satisfied.[8]

Once the Army of Humayun had made its charge, and Sher Shah's troops made their agreed-upon retreat, the Mughal troops relaxed their defensive preparations, returning to their entrenchments without posting a proper guard. Observing the Mughals' vulnerability, Sher Shah reneged on his earlier agreement. That very night, his army approached the Mughal camp and finding the Mughal troops unprepared with a majority asleep, they advanced and killed most of them. The Emperor survived by swimming the Ganges using an air-filled "water skin," and quietly returned to Agra.[7][4]

In Agra

When Humayun returned to Agra, he found that all three of his brothers present. Humayun once again not only pardoned his brothers for plotting against him, but even forgave Hindal for his outright betrayal. Some have argued that Humayun forgave from a weak position, unable to inflict punishment on his brothers in any case. With his armies travelling at a leisurely pace, Sher Shah gradually drew closer and closer to Agra. That posed a serious threat to the entire family, but still Humayun and Kamran squabbled over how to proceed. Kamran withdrew after Humayun refused to make a quick attack on the approaching enemy, instead opting to build a larger army under his own name. When Kamran returned to Lahore, his troops followed him shortly afterwards, and Humayun, with his other brothers Askari and Hindal, marched to meet Sher Shah just 240 kilometres (150 miles) east of Agra at the Battle of Kanauj on May 17, 1540. The battle once again saw Humayun make some tactical errors, his army resoundingly defeated. He and his brothers quickly retreated back to Agra, humiliated and mocked along the way by peasants and villagers. They chose to leave Agra, retreating to Lahore, though Sher Shah followed them, founding the short-lived Sur Dynasty of northern India with its capital at Delhi.

In Lahore

The four brothers united in Lahore, but every day they received intelligence that Sher Shah drew closer and closer. When he reached Sirhind, Humayun sent an ambassador carrying the message; "I have left you the whole of Hindustan (i.e., the lands to the East of Punjab, comprising most of the Ganges Valley). Leave Lahore alone, and let Sirhind be a boundary between you and me." Sher Shah replied; "I have left you Kabul. You should go there." Kabul served as the capital of the empire of Humayun's brother Kamran Mirza, far from willing to hand over any of his territories to his brother. Instead, Kamran approached Sher Shah, and proposed that he actually revolt against his brother and side with Sher Shah in return for most of the Punjab. Sher Shah dismissed his help, believing he could take the region without help, though word soon spread to Lahore about the treacherous proposal. Many urged Humayun to make an example of Kamran and kill him. Humayun refused, citing the last words of his father, Babur "Do nothing against your brothers, even though they may deserve it.[9]

Withdrawing further

Humayun decided that it would be wise to withdraw still further. He asked that his brothers join him as he fell back into Sindh. While the previously rebellious Hindal remained loyal, Kamran and Askari instead decided to head to the relative peace of Kabul, the definitive schism in the family.

Humayun expected aid from the Amir of Sindh, whom he had appointed and who owed him his allegiance. While the Amir, Hussein, tolerated Humayun's presence, he knew that raising an army against Sher Shah would ultimately end in disaster, and he therefore politely refused all of Humayun's requests for military assistance. While in Sindh, Humayun met and married Hamidaâwho became the mother of Akbarâon August 21, 1541. Humayun selected the date after consulting his astrolabe to check the location of the planets.

In May 1542 the Raja of Jodhpur, Rao Maldeo Rathore, issued a request to Humayun to form an alliance against Sher Shah and so Humayun and his army rode out through the desert to meet with the Prince. As they made their way across the desert the prince became aware of how feeble Humayun's army had now become. Furthermore, Sher Shah had offered him more favorable terms and so he sent word that he no longer wanted to see Humayun, now less than 80 km (50 miles) from the city. Thus, Humayun and his troops, and his heavily pregnant wife, had to retrace their steps through the desert at the hottest time of year. All the wells had been filled with sand by the nearby inhabitants after Humayun's troops had killed several cows (a sacred animal to the Hindus), leaving them with nothing but berries to eat. When Hamida's horse died no one would lend the Queen (now eight months pregnant) a horse, so Humayun did so himself, resulting in him riding a camel for six kilometers (four miles), although Khaled Beg then offered him his mount. Humayun later described that incident as the lowest point in his life. He ordered Hindal to join his brothers in Kandahar.

While Humayun ventured on his travels, Hussein, the Amir of Sindh, had killed Maldeo's father, prompting the Raja to change his mind about Humayun. He decided to ride out to meet him in Umarkot, a small town by a desert oasis. He afforded Humayun full courtesies, giving him new horses and weapons as the men formed an alliance against Sindh. Umarkot became the center of operations for the battle and here, on October 15, 1542, 15-year-old Hamida gave birth to her first child, a boy they called Akbar (great), the heir-apparent to the 34-year-old Humayun.

Retreat to Kabul

The war against Sindh had led to a stalemate, and so Hussein decided to bribe Humayun to leave the area. Humayun accepted and, in return for three hundred Camels (mostly wild) and two thousand loads of grain, he set off to join his brothers in Kandahar, crossing the Indus on July 11, 1543.

In Kamran's territory, Hindal had been placed under house arrest in Kabul after refusing to have the Khutba recited in Kamran's name. He ordered his other brother, Askari, to gather an army and march on Humayun. When Humayun received word of the approaching hostile army, he decided against facing them and, instead, sought refuge elsewhere. Akbar remained behind in camp close to Kandahar for, as the December cold weather made including fourteen month old toddler in the forthcoming march through the dangerous and snowy mountains of the Hindu Kush impossible. Askari found Akbar in the camp, and embraced him, and allowed his own wife to rear him. She apparently treated him as her own.

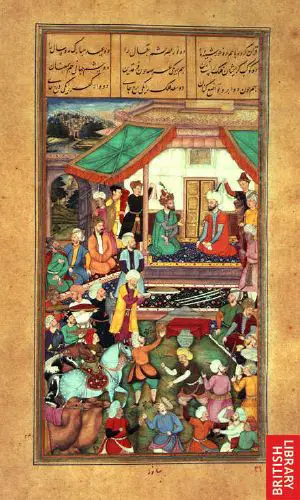

Refuge in Persia

Humayun fled to the refuge of the Safavid Empire in Iran, marching with forty men and his wife and her companion through mountains and valleys. Among other trials, the Imperial party had been forced to live on horse meat boiled in the soldiers' helmets. Those indignities continued during the month it took them to reach Herat. After their arrival, they rediscovered the finer things in life. Upon entering the city his army received an armed escort, lavish food and clothing. They stayed in fine accommodations, the roads cleared and cleaned before them. Shah Tahmasp, unlike Humayun's own family, actually welcomed the Mughal, and treated him as a royal visitor. Here Humayun went sightseeing, viewing the Persian artwork and architecture with amazement: much of that had been created by the Timurid Sultan Husayn Bayqarah and his ancestor, princess Gauhar Shad, thus he admired the work of his relatives and ancestors at first hand. He viewed the work of the Persian miniaturists for the first time, and Kamaleddin Behzad had two of his pupils join Humayun in his court. Humayun expressed amazement at their work and asked if they would work for him if he regained the sovereignty of Hindustan: they agreed. With so much going on, Humayun's meeting with the Shah waited until July, some six months after his arrival in Persia. After a lengthy journey from Herat the two met in Qazvin where a large feast and parties highlighted the event. A famous wall-painting in the Chehel Sotoun (Forty Columns) palace in Esfahan depicts the meeting of the two monarchs.

The Shah urged that Humayun convert from Sunni to Shia Islam, hinting that that would be the price of his support, and eventually and reluctantly Humayun did so, much to the disapproval of his biographer Jauhar. With that outward acceptance of Shi'ism, the Shah prepared to offer Humayun more substantial support. When Humayun's brother, Kamran, offered to cede Kandahar to the Persians in exchange for Humayun, dead or alive, the Shah refused. Instead the Shah threw a party for Humayun, with three hundred tents, an imperial Persian carpet, twelve musical bands and "meat of all kinds." Here the Shah announced that all that, and 12,000 choice cavalry would to lead an attack on his brother Kamran. Shah asked only that, if Humayun's forces proved victorious, Kandahar would be his.

Kandahar and Onwards

With this Persian aid Humayun took Kandahar from Askari after a two-week siege. He noted how the nobles who had served Askari quickly flocked to serve him, "in very truth the greater part of the inhabitants of the world are like a flock of sheep, wherever one goes the others immediately follow." He gave Kandahar, as agreed, to the Shah who sent his infant son, Murad, as the Viceroy. The baby soon died and Humayun thought himself strong enough to assume power.

Humayun now prepared to take Kabul, ruled by his brother Kamran. In the end, Humayun found a siege unnecessary. Kamran had become a detested leader and, as Humayun's Persian army approached the city, hundreds of Kamran's troops changed sides, flocking to join Humayun and swelling his ranks. Kamran absconded and began building an army outside the city. In November 1545 Hamida and Humayun reunited with their son Akbar, and held a huge feast. They also held another, larger, feast in the child's' honor when he received circumcised.

While Humayun had a larger army than his brother and had the upper hand, on two occasions his poor military judgment allowed Kamran to retake Kabul and Kandahar, forcing Humayun to mount further campaigns for their recapture. He may have been aided in that by his reputation for leniency towards the troops who had defended the cities against him, as opposed to Kamran, who marked his brief periods of possession with atrocities against the inhabitants who, he supposed, had helped his brother.

His youngest brother, Hindal, formerly the most disloyal of his siblings, died fighting on his behalf. His brother Askari, shackled in chains at the behest of his nobles and aides, went on Hajj, dying en route in the desert outside Damascus.

Humayun's other brother, Kamran, had repeatedly sought to have Humayun killed, and when in 1552 he attempted to make a pact with Islam Shah, Sher Shah's successor, Gakhar apprehended him. The Gakhars represented one of only a few groups of people who had remained loyal to their oath to the Mughals. Sultan Adam of the Gakhars handed Kamran over to Humayun. Although Humayun felt tempted to forgive his brother, he received a warning that allowing Kamran's continuous acts to go unpunished could foment rebellion within his own ranks. So, instead of killing his brother, Humayun had Kamran blinded which would end any claim to the throne. He sent him on Hajj, as he hoped to see his brother absolved of sin, but he died close to Mecca in the Arabian desert in 1557.

India Revisited

Sher Shah Suri had died in 1545, and, although he had been a powerful ruler, his son Islam Shah died too in 1554. Those two deaths left the dynasty reeling and disintegrating. Three rivals for the throne all marched on Delhi, while in many cities leaders tried to stake a claim for independence. That proved a perfect opportunity for the Mughals to march back to India. Humayun placed the army under the able leadership of Bairam Khan. A wise move, given Humayun's own record of military ineptitude, that turned out to be prescient, as Bairam proved himself one of the world's great legendary tacticians.

Bairam Khan led the army through the Punjab virtually unopposed. The fort of Rohtas, built between 1541 to 1543 by Sher Shah Sur to crush the Gakhars loyal to Humayun, surrendered without a shot by a traitorous commander. The walls of the Rohtas Fort measure up to 12.5 meters in thickness and up to 18.28 meters in height. They extended for four km and featured 68 semi-circular bastions. Its sandstone gates, both massive and ornate, exerted a profound influence on Mughal military architecture.

Sikander Suri offered the only major battle against Humayun's armies in Sirhind, where Bairam Khan employed a tactic whereby he engaged his enemy in open battle, but then retreated quickly in apparent fear. When the enemy followed after them, entrenched defensive positions easily annihilated them. From here on most towns and villages chose to welcome the invading army as it made its way to the capital. On July 23, 1555 Humayun, once again, sat on Babur's throne in Delhi.

Ruling North India Again

With all of his brothers now dead, Humayun had unrivaled control of the throne during military campaigns. An established leader, he could trust his generals. With that new-found strength Humayun embarked on a series of military campaigns aimed at extending his reign over areas to the East and West. His sojourn in exile seems to have reduced Humayun's reliance on astrology, and his military leadership instead imitated the methods he had observed in Persia, allowing him to win more effectively and quicker.

That also applied to the administration of the empire. Humayun imported Persian methods of governance into North India during his reign. The system of revenue collection improved on both the Persian model and that of the Delhi Sultanate one. The Persian arts too became influential, with Persian-style miniatures produced at Mughal (and subsequently Rajput) courts. The Chaghatai Language, in which Babur had written his memoirs, disappeared almost entirely from the culture of the courtly elite, and Akbar never spoke it. Later in life Humayun himself spoke in Persian verse more often than not.

| Preceded by: Babur |

Mughal Emperor 1530â1539 |

Succeeded by: Sher Shah (Sultan of Delhi) |

| Preceded by: Ibrahim Suri (Sultan of Delhi) |

Mughal Emperor (Restored) 1555â1556 |

Succeeded by: Akbar |

Death and Legacy

| Humayun's Tomb, Delhi* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv |

| Reference | 232 |

| Region** | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1993Â (17th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

Humanyu's death

On February 22, 1556, Humayun, his arms full of books, descended the staircase from his library when the Muezzin announced the Ezan (the call to prayer). As his habit, wherever he heard the summons, he bowed his knee in holy reverence. Kneeling, he caught his foot in his robe, tumbled down several steps and hit his temple on a rugged stone edge. He died three days later, the 13-year-old Akbar succeeded him.

Humayun loved astrology and astronomy and built observatories that lasted centuries. His sister Gulbadan Begum, at the request of his son, Akbar, chronicled his life in a slightly hagiographical work called the Humayun-nama. His most lasting impact had been the importing of Persian ideas into the Indian empire, something expanded by later leaders. His support for the arts, following exposure to Safavid art, saw him recruit painters to his court who developed the celebrated Mughal style of painting. Humayun's greatest architectural creation, the Din-Panah (Refuge of Religion) citadel at Delhi, had been destroyed by Sher Shah. Humayun's Tomb, built by his widow after his death, serves as the best reminder of his rule. The Gur-e Amir in Samarkand provided the ultimate model for Humayun's tomb, the best-known as a precursor to the Taj Mahal in style. In its striking composition of dome and iwan, and its imaginative use of local materials, the tomb stands as one of the finest Mughal monuments in India in its own right.

Humayun's tomb

Humayun's tomb designates a complex of buildings of Mughal architecture located Nizamuddin east, New Delhi. Sultan Kequbad S/o Nasiruddin (1268-1287 C.E.) ruled the land during the Slave Dynasty, establishing the city as his capital and ruling from the KiloKheri Fort. The tomb complex rose on the former site of Nasiruddin's KiloKheri Fort. The Humayun Tomb Complex, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, encompasses the main tomb of Emperor Humayun as well as numerous other structures, providing the first example Mughal architecture in India. The mausoleum style later manfested in the Taj Mahal in Agra.

Hamida Banu Begum, Humayun's widow, ordered the construction of the tomb of Humayun in 1562 C.E. The architect of the edifice, reportedly Sayyed Muhammad ibn Mirak Ghiyathuddin and his father Mirak Ghiyathuddin, came from Herat. The tomb required eight years to build; the Ghiyathuddin father and son constructed the tomb in Chahr Bagh Garden style, the first of its kind in the region.

The Aga Khan Trust for Culture[1] completed restoration work in March 2003, enabling water to flow through the watercourses in the gardens once more. His Highness the Aga Khan's foundation provided funding for that work to India. AKTC has undertaken the restoration at Babur's tomb, the resting place of Humayun's father in Kabul.

Gallery

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 Å araf ad-DÄ«n Ê»AlÄ« YazdÄ«, and Ê»Iá¹£Äm ad-Din Urunbaev, áºafarnÄma (1972).

- â Svatopluk Soucek, A History of Inner Asia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 9780521651691).

- â Aḥmad NiáºÄm al-DÄ«n, Brajendranath De, and Baini Prashad, The TabaqÄt-I-AkbarÄ« of _K_HwÄjah NiáºÄmuddÄ«n Aḥmad (A History of India from the Early MusalmÄn Invasions to the Thirty-Sixth Year of the Reign of Akbar of Khwájah Nizámuddin Ahmad) Bibliotheca Indica, [225 : 2, 225 : 3 : 1-2]. (Calcutta: Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1936).

- â 4.0 4.1 4.2 Rama Shanker Avasthy, The Mughal Emperor Humayun (Allahabad: History Dept., University of Allahabad, 1967).

- â 5.0 5.1 Sukumer Banerji, HumÄyÅ«n BÄdshÄh ([London]: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1938).

- â 6.0 6.1 Jauhar ÄftÄbcÄ« and S. Moinul Haq, Taz̤kirat al-vÄqiÊ»Ät (KarÄcÄ«: PÄkistÄn Historikal SosÄʼitÄ«, 1955).

- â 7.0 7.1 7.2 Bamber Gascoigne, A Brief History of the Great Moghuls( London: Robinson, 2002, ISBN 9781841195339).

- â BadÄʼūnÄ«, Ê»Abd al-QÄdir ibn MulÅ«k ShÄh. Muntak̲h̲abu-T-TawÄrÄ«k̲h̲ (Patna: Academica Asiatica, 1973).

- â AbÅ« al-Faz̤l ibn MubÄrak and Henry Beveridge, The Akbar Nama of Abu-L-Fazl History of the Reign of Akbar, Including an Account of His Predecessors (New Delhi: Ess Ess Publications, 1985).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alam, Muzaffar, and Sanjay Subrahmanyam. The Mughal State, 1526-1750. Oxford in India readings. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 9780195652253

- Begum, Gulbadan. Humayun-nama the history of Humayun. Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications, 2002. ISBN 9789693513080

- Crooke, William, and James Tod. Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, or, the Central & Western Rajpoot States of India. Andesite Press, 2015 (original 1902). ISBN 978-1298775054

- Gascoigne, Bamber. A Brief History of the Great Moghuls. London: Robinson, 2002. ISBN 9781841195339

- Gommans, Jos J. L. Mughal Warfare Indian Frontiers and Highroads to Empire, 1500-1700. Warfare and history. London: Routledge, 2002. ISBN 9780415239882

- Irvine, William. The Army of the Indian Moghuls Its Organization and Administration. Forgotten Books, 2018 (original 1903). ISBN 978-0331633528

- Jackson, Peter. The Delhi Sultanate A Political and Military History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0521543290

- Richards, John F. The Mughal Empire. The New Cambridge history of India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0521566032

- Soucek, Svatopluk. A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 9780521651691

External links

All links retrieved July 19, 2024.

- Humayun's Tomb, Delhi UNESCO World Heritage Convention

- Photos of Humayun's Tomb

- Humayun's Tomb

- The Mughals: Humayun by Abhijit Rajadhyaksha, The History Files

| |||||||

| Emperors: | Babur - Humayun - Akbar - Jahangir - Shah Jahan - Aurangzeb - Lesser Mughals |

| Events: | First battle of Panipat - Second battle of Panipat - Third battle of Panipat |

| Architecture: | Humayun's Tomb - Agra Fort - Badshahi Mosque - Lahore Fort - Red Fort - Taj Mahal - Shalimar Gardens - Pearl Mosque - Bibi Ka Maqbara - See also |

| Adversaries: | Ibrahim Lodhi - Sher Shah Suri - Hemu - Shivaji - Guru Gobind Singh |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.