Egg (biology)

In biology, egg may refer to a single female reproductive cell (or gamete), which is also called an ovum (plural ova), from the Latin word for egg. However, the term also may be used as in most birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and insects to describe the entire reproductive body comprising a protective enclosure and the stored nutrients and developing embryo within it.

In contrast to the male gamete, or sperm, the egg, in the sense of the female reproductive cell, contains more than just genetic material (DNA): it often includes nutrients (most of which are present in the yolk) and a protective covering, which may range from a single membrane in some invertebrates to the tough outer shell of many bird eggs. Its multiple functions explain the egg's large size relative to spermatozoa and other cells: the ovum is the largest cell in the human body, typically visible to the naked eye without the aid of a microscope. Plant eggs are the exception because they do not need to contain nutritive materials; the developing sporophyte embryo is nourished until self-supporting by the plant on which it is formed.

Like spermatozoa, eggs are haploid, meaning that they contain one set of chromosomes. In some species that engage in a form of asexual reproduction called parthenogenesis, the eggs remain unfertilized; that is, they do not join with male gametes to produce diploid cells (which contain two sets of chromosomes). A fertilized egg, in contrast, is called a zygote.

While eggs are essential to an organism's purpose of reproduction, those eggs whose developmental cycle includes a period of maturing outside the mother's body are vulnerable to predation by animals and and susceptible to harvesting by humans. In this way eggs provide a larger benefit, being consumed by many animals and by humans. Eggs' wide diversity of colors and shapes also adds to the human enjoyment of nature.

Main types of egg development

There are three main devices for egg development among animals:

- Oviparous animals lay eggs in the environment, and the embryos inside consequently develop outside of the mother’s body. The eggs of terrestrial animals, such as birds, cannot mature in aquatic environments and are protected from drying out inside by a waterproof outer membrane or shell, which can also be effective protection against predators.

- In viviparous animals, which include humans and all other placental mammals, the embryo develops inside the uterus, receiving nutrition directly from the mother; hence, the egg does not require vast stores of nutrients to survive the early stages of development, nor does it need a hard outer shell for protection.

- Non-mammals such as sharks retain the eggs in the mother’s body until they hatch, but do not directly nourish the embryo; they engage in an intermediate reproductive system called ovoviviparity.

As depicted in the photographs below, eggs come in various sizes, colors, and shapes, which reflect specific adaptations that confer a reproductive advantage. Even among bird eggs, the diversity is astounding. The 1.5 kg ostrich egg contains the largest existing single cell currently known, while the bee hummingbird produces the smallest-known bird egg, weighing only half a gram. The texture of bird eggshells ranges from the rough and chalky cormorant eggs to the oily and waterproof duck eggs.

A baby tortoise emerges from its egg.

Fish eggs, such as these herring eggs, are often transparent in appearance.

Components

With the exception of the eggs of some cnidarians, all animal eggs (ova) are enclosed by a membrane called the vitelline membrane, comprising mainly protein fibers and the protein receptors needed for sperm binding during fertilization. Higher vertebrates and many invertebrates have one or more additional membranes. Insects eggs are encased by a thick, hard chorion, while amphibian eggs have a protective jelly layer. A bird egg also contains two shell membranes plus the shell, which is the outermost membrane.

Many animal eggs contain the egg white (also known as the albumen), which is the cytoplasm of the cell that serves to protect the egg yolk and nourish the embryo, being rich in proteins. The egg yolk, which contains the egg nucleus and associated nutritive materials, is suspended in the albumen by one or two spiral bands of tissue called chalazae (singular: chalaza).

Egg maturation

Mature eggs (ova) remain functional for a relatively short period before degenerating; thus, many eggs are stored as immature ova called oocytes and oogonia. In the ovarian cycles of placental mammals, for example, the oocyte fully matures and is released by the female gonads (the ovaries).

In species that repeatedly release hundreds or thousands of eggs, oogonia remain capable of division via mitosis throughout life. In animals that produce relatively few eggs throughout their life span, the proliferation of oogonia occurs during an early period in which the individual's entire store of egg precursor cells form (in humans, this period ends before birth). At birth, a female human has about a million primary oocytes in each ovary; by the time of sexual maturity, the number has dwindled to only 200,000.

Evolution of the egg

Reptiles were the first vertebrate group to solve the problem of reproduction in a terrestrial (versus aquatic) environment, a solution that was later shared by birds. Reptiles evolved a shelled egg that is both permeable to respiratory gases and relatively impermeable to water. The shelled egg created a new problem for fertilization, however: sperm cannot penetrate the shell, so they must fertilize the egg before the shell forms.

A solution to this problem was internal fertilization, which required the evolution of accessory organs in the female reproductive system. Most mammals have retained internal fertilization but have eliminated the shelled egg by keeping the developing embryo in the female reproductive tract until it is capable of surviving independently in the external environment.

Reproductive strategies

Oviparity

In the oviparous animals (all birds and most fishes, amphibians, and reptiles), the ova develop protective layers and pass through the oviduct to the outside of the body. The embryo is nourished by nutrients contained in the egg until it hatches.

Among the oviparous animals, there is still great diversity in the method of fertilization and the relative involvement of one or more parents in the embryo's development. For example, the egg may be fertilized by male sperm either inside the female body (as in birds), or outside (as in many fishes).

In the latter strategy, large numbers of eggs are laid at one time (an adult female cod can produce 4‚Äď6 million eggs in one spawning), and the eggs are then left to develop without parental care. When the larvae hatch from the egg, they often carry the remains of the yolk in a yolk sac, which continues to nourish the larvae for a few days as they learn how to swim. Once the yolk is consumed, there is a critical point after which they must learn how to hunt and feed in order to survive.

Like fish eggs, amphibian eggs are jellylike and are fertilized externally. They also do not have a shell and therefore need to be laid in water or protective foam, as with the Coast foam-nest treefrog (Chiromantis xerampelina).

Reptile eggs are often rubbery and are always initially white. Often the sex of the developing embryo is determined by the temperature of the surroundings, with cooler temperatures favoring males. Not all reptiles lay eggs, however; some are viviparous.

Bird eggs are laid by females and incubated (i.e., kept at a constant temperature required for development) for a time that varies according to the species. Depending on the species, the female or male is responsible for incubating; in some species, such as the Whooping Crane, the male and female take turns incubating the eggs.

Mammalian eggs are laid only by Australian monotremes: i.e., the platypus and two genera of echidna (spiny anteaters). Like birds eggs, monotreme eggs are fertilized internally.

Ovoviviparity

A few fish, notably the rays and most sharks, as well as some reptiles and many invertebrates, use an intermediate reproductive form called ovoviviparity. The eggs are fertilized and develop internally, but the larvae rely on the egg yolk rather than direct nourishment from the mother. The mother then gives birth to relatively mature young. In certain instances, the most physically developed offspring will devour its smaller siblings for further nutrition while still within the mother's body, a phenomenon known as intrauterine cannibalism.

Viviparity

Among the viviparous animals, eggs are fertilized internally and the developing embryo receives direct nourishment internally once the egg is attached to the wall of the uterus. Mammals are the best example, but viviparity has also evolved independently in other animals, such as in scorpions, some sharks (such as the hammerhead shark and reef shark), and velvet worms.

Shelled eggs

The eggs of terrestrial vertebrates such as reptiles, birds, and monotremes (mammals that lay eggs rather than giving birth) are surrounded by a protective shell, which may be either flexible or inflexible.

For terrestrial animals, the shell must be tough and waterproof, to prevent the eggs from drying out and to serve as protection against predators. However, the shell must also be semi-permeable to enable the exchange of gases (carbon dioxide and oxygen) necessary for life. Thus, tiny pores in bird eggshells allow the embryo to breathe. The domestic hen egg, for example, has around 7,500 pores.

Shape

Most bird eggs have an oval shape, with one end rounded and the other more tapered. This shape results from the egg being forced through the oviduct of the mother. Muscles contract the oviduct behind the egg, pushing it forward. The egg's wall is still malleable when released by the female, thus the pointed end develops at the back side. Cliff-nesting birds often have highly conical eggs, which are less likely to roll off the cliff edge, tending instead to roll around in a tight circle, and thus are believed to have been selected for by evolution. In contrast, many hole-nesting birds have nearly spherical eggs.

Color

The default color of shelled vertebrate eggs is the white of the calcium carbonate from which the shells are made; however, most passerines (commonly known as perching birds), which represent more than half of bird species, produce colored eggs. The pigments biliverdin and its zinc chelate provide a green or blue ground color, while protoporphyrin produces reds and browns used as a base color or as spotting.

Color serves as a means of disguising eggs from predators. Although non-passerines typically have white eggs, some ground-nesting groups such as the Charadriiformes, sandgrouse and nightjars, for example, use color as camouflage. Conversely, color can also be a method of offense rather than defense: some parasitic cuckoos use color to match the passerine host's egg, tricking the host into raising their young.

Pigmentation may also serve a nutritive role. For example, a recent study suggests that the protoporphyrin markings on passerine eggs act to reduce brittleness by acting as a solid-state lubricant. If there is insufficient calcium available in the local soil, the egg shell may be thin, especially in a circle around the broad end. Protoporphyrin speckling compensates for this, and increases inversely to the amount of calcium in the soil. For the same reason, later eggs in a clutch are more spotted than early ones as the female's store of calcium is depleted. It used to be thought that color was applied to the shell immediately before laying, but this research shows that coloration is an integral part of the development of the shell, with the same protein responsible for depositing calcium carbonate or protoporphyrins when there is a lack of that mineral.

The color of individual eggs is also genetically influenced, and appears to be inherited through the mother only, suggesting that the gene responsible for pigmentation is on the sex determining W chromosome (female birds are WZ; males, ZZ). In species such as the common guillemot, which nest in large groups, each female's eggs have very different markings, making it easier for females to identify their own eggs on the crowded cliff ledges on which they breed.

Predation and parasitism

Although the primary purpose of eggs is reproductive, many animals, including most humans, feed on eggs. For example, principal predators of the Black oystercatcher's eggs include raccoons, skunks, minks, river and sea otters, gulls, crows, and foxes. The stoat (Mustela erminea) and long-tailed weasel (M. frenata) steal duck eggs. Snakes of the genera Dasypeltis and Elachistodon specialize in eating eggs.

Avian brood parasitism occurs when the brood-parasite lays its eggs in the nest of another bird of either the same or a different species, manipulating host individuals to raise its young. This relieves the parasitic parent from the investment of rearing young or building nests, enabling them to devote more time and energy to feeding themselves and producing more offspring. In some cases, the host's eggs are removed or eaten by the female, or expelled by her chick. Brood parasites include the cowbirds and many Old World cuckoos.

Protist and plant ova

In protists, fungi, and many plants, such as bryophytes, ferns, and gymnosperms, ova are produced inside archegonia, multicellular structures often located on the surface. Since the archegonium is a haploid structure, egg cells are produced via mitosis. The typical bryophyte archegonium consists of a long neck with a wider base containing the egg cell. Upon maturation, the neck opens to allow sperm cells to swim into the archegonium and fertilize the egg. The resulting zygote then gives rise to an embryo, which will grow out of the archegonium as a sporeling (a young sporophyte).

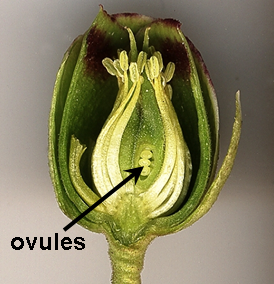

In the flowering plants, the female gametophyte, which usually gives rise to the archegonium, has been reduced to just eight cells (referred to as the embryo sac) inside the ovule. The gametophyte cell closest to the opening of the embryo sac develops into the egg cell. Upon pollination, a pollen tube delivers sperm into the embryo sac, and one sperm nucleus fuses with the egg nucleus. The resulting zygote develops into an embryo inside the ovule. The ovule in turn develops into a seed and in many cases the plant ovary develops into a fruit to facilitate the dispersal of the seeds. Upon germination, the embryo grows into a seedling.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alberts, B., R. Heald, A. Johnson, D. Morgan, M. Raff, K. Roberts, and P. Walter. 2022. Molecular Biology of the Cell. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393884821

- Gosler, A. 2006. Yet even more ways to dress eggs. British Birds 99(7):338-53.

- Sadava, D.E., D.M. Hillis, H.C. Heller, and S.D. Hacker. 2016. Life: The Science of Biology. W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-1319010164

External links

All links retrieved April 17, 2025.

- Anatomy of an Egg Exploratorium

- Appliance Science: The biology of the chicken egg CNET

- Study reveals how egg cells get so big MIT News

- At Long Last, How Plants Make Eggs UC Davis

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Egg_(biology)  history

- Ovum  history

- Egg_white  history

- Egg_yolk  history

- Passerine  history

- Vitelline_membrane  history

- Monotreme  history

- Vivipary  history

- Incubation  history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.