Xiongnu

The Xiongnu (Chinese: 匈奴; pinyin: Xiōngnú; Wade-Giles: Hsiung-nu); were a nomadic people from Central Asia, generally based in present day Mongolia and China. From the 3rd century B.C.E. they controlled a vast steppe empire extending west as far as the Caucasus. They were active in the areas of southern Siberia, western Manchuria and the modern Chinese provinces of Inner Mongolia, Gansu and Xinjiang. Very ancient (perhaps legendary) historic Chinese records say that the Xiongnu descended from a son of the final ruler of China's first dynasty, the Xia Dynasty, the remnants of which were believed by the Chinese of the Spring and Autumn Period to be the people of the state of Qǐ (杞). However, due to internal differences and strife, the Xiongnu fled north and north-west.

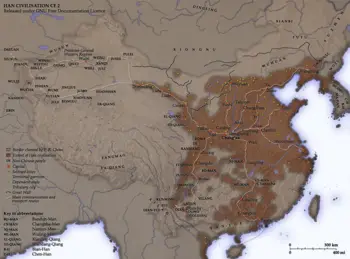

Relations between the Han Chinese and the Xiongnu were complicated and included military conflict, exchanges in tribute and trade, and marriage treaties.

The overwhelming amount of information on the Xiongnu comes from Chinese sources. What little is known of their titles and names come from Chinese transliterations. Only about 20 words belonging to the Altaic languages are known[1], and only a single sentence from Chinese documents.

Origins, languages and early history of the Xiongnu

The original geographic location of Xiongnu is generally placed at the Ordos. According to Sima Qian, the Xiongnu were descendants of Chunwei (淳維), possibly a son of Jie, the final ruler of the Xia Dynasty. However, while there is no direct evidence contradicting this theory, there is no direct evidence supporting it either.

The language of Xiongnu reflects without any scholarly consensus, based on the analysis between early 19th century to 20th century different opinions were proposed; proponents of the Turkic languages included Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat, Julius Klaproth, Shiratori Kurakichi, Gustaf John Ramstedt, Annemarie von Gabain and Omeljan Pritsak, while others; like Paul Pelliot insisted a Mongolic origin; Albert Terrien de Lacouperie considered them to be multi component groups.[2]

Lajos Ligeti was the first to suggest that the Xiongnu spoke a Yeniseian language. In the early 1960s Edwin Pulleyblank was the first to expand upon this idea with credible evidence. In 2000, Alexander Vovin reanalyzed Pulleyblank's argument and found further support for it by utilizing the most recent reconstruction of Old Chinese phonology by Starostin and Baxter and a single Chinese transcription of a sentence in the language of the Jie (a member tribe of the Xiongnu confederacy). Previous Turkic interpretations of the aforementioned sentence do not match the Chinese translation as precisely as using Yeniseian grammar.[3]

Recent genetics research dated 2003[4] confirms the studies[5] indicating that the Turkic peoples,[6] originated from the same area and therefore are possibly related.

As archaeological indicate, petroglyph sites in Yinshan and Helanshan dated from the 9th millennium B.C.E. to 19th century had been discoverd, the rock art of the Yinshan and Helanshan consists mainly of engraved signs (petroglyphs) and only minimally of painted images.[7] Through gathered data, scholar like Ma Liqing had make a comparison between the petroglyphs (which he presumed to be the sole extant of possible Xiongnu's writings), and the Orkhon script (the earliest known Turkic alphabet) recently, and argued a new connection between both of them.[8]

Early history

Confederation under Modu

In 209 B.C.E., just three years before the founding of the Han Dynasty, the Xiongnu were brought together in a powerful confederacy under a new shanyu named Modu Shanyu (known as Modu to Chinese and Mete in Turkish). The Xiongnu's political unity transformed them into a much more formidable foe by enabling them to concentrate larger forces and exercise better strategic coordination. The cause of the confederation, however, remains unclear. It has been suggested that the unification of China prompted the nomads to rally around a political centre in order to strengthen their position.[9] Another theory is that the reorganisation was their response to the political crisis that overtook them 215 B.C.E., when Qin armies evicted them from pastures on the Yellow River.[10]

After forging internal unity, Modun expanded the empire on all sides. To the north he conquered a number of nomadic peoples, including the Dingling of southern Siberia. He crushed the power of the Donghu of eastern Mongolia and Manchuria, as well as the Yuezhi in the Gansu corridor. He was able, moreover, to recover all the lands taken by the Qin general Meng Tian. Before the death of Modun in 174 B.C.E., the Xiongnu had driven the Yuezhi from the Gansu corridor completely and asserted their presence in the Western Regions in modern Xinjiang.

Nature of the Xiongnu state

Under Modun, a dualistic system of political organisation was formed. The left and right branches of the Xiongnu were divided on a regional basis. The shanyu or shan-yü — supreme ruler equivalent to the Chinese "Son of Heaven" — exercised direct authority over the central territory. The Longcheng (蘢城), near Koshu-Tsaidam in Mongolia, was established as the annual meeting place and de facto capital.

The marriage treaty system

In the winter of 200 B.C.E., following a siege of Taiyuan, Emperor Gao personally led a military campaign against Modun. At the battle of Baideng, he was ambushed reputedly by 300,000 elite Xiongnu cavalry. The emperor was cut off from supplies and reinforcements for seven days, only narrowly escaping capture.

After the defeat at Pingcheng, the Han emperor abandoned a military solution to the Xiongnu threat. Instead, in 198 B.C.E., the courtier Liu Jing (劉敬) was despatched for negotiations. The peace settlement eventually reached between the parties included a Han princess given in marriage to the shanyu (called heqin 和親 or "harmonious kinship"); periodic gifts of silk, liquor and rice to the Xiongnu; equal status between the states; and the Great Wall as mutual border.

This first treaty set the pattern for relations between the Han and the Xiongnu for some sixty years. Up to 135 B.C.E., the treaty was renewed no less than nine times, with an increase of "gifts" with each subsequent agreement. In 192 B.C.E., Modun even asked for the hand of the widowed Empress Lü. His son and successor, the energetic Jiyu (稽粥), known as the Laoshang Shanyu (老上單于), continued his father's expansionist policies. Laoshang succeeded in negotiating with Emperor Wen, terms for the maintenance of a large-scale government-sponsored market system.

While much was gained by the Xiongnu, from the Chinese perspective marriage treaties were costly and ineffective. Laoshang showed that he did not take the peace treaty seriously. On one occasion his scouts penetrated to a point near Chang'an. In 166 B.C.E. he personally led 140,000 cavalry to invade Anding, reaching as far as the imperial retreat at Yong. In 158 B.C.E., his successor sent 30,000 cavalry to attack the Shang commandery and another 30,000 to Yunzhong.

War with Han China

Han China was making preparations for a military confrontation from the reign of Emperor Wen. The break came in 133 B.C.E., following an abortive trap to ambush the shanyu at Mayi. By that point the empire was consolidated politically, militarily, and financially, and was led by an adventurous pro-war faction at court. In that year, Emperor Wu reversed the decision he had made the year before to renew the peace treaty.

Full scale war broke out in autumn 129 B.C.E., when 40,000 Chinese cavalry made a surprise attack on the Xiongnu at the border markets. In 127 B.C.E., the Han general Wei Qing retook the Ordos. In 121 B.C.E., the Xiongnu suffered another setback when Huo Qubing led a force of light cavalry westward out of Longxi and within six days fought his way through five Xiongnu kingdoms. The Xiongnu Hunye king was forced to surrender with 40,000 men. In 119 B.C.E. both Huo and Wei, each leading 50,000 cavalrymen and 100,000 footsoldiers, and advancing along different routes, forced the shanyu and his court to flee north of the Gobi Desert.[11]

Major logistical difficulties limited the duration and long-term continuation of these campaigns. According the analysis of Yan You (嚴尤), the difficulties were twofold. Firstly there was the problem of supplying food across long distances. Secondly, the weather in the northern Xiongnu lands was difficult for Han soldiers, who could never carry enough fuel.[12] According to official reports, Xiongnu's side lost 80,000 to 90,000 men. And out of the 140,000 horses the Han forces had brought into the desert, fewer than 30,000 returned to China.

As a result of these battles, the Chinese controlled the strategic region from the Ordos and Gansu corridor to Lop Nor. They succeeded in separating the Xiongnu from the Qiang peoples to the south, and also gained direct access to the Western Regions.

Ban Chao, Protector General (都護; Duhu) of the Han Dynasty embarked with an army of 70,000 men in a campaign against the Xiongnu insurgents who were harassing the trade route we now know as the Silk Road. His successful military campaign saw the subjugation of one Xiongnu tribe after another, and those fleeing Xiongnu insurgents were pursued by Ban Chao's army of entirely mounted-infantry and light cavalry over an extremely vast distance westward into the territory of the Parthians and beyond the Caspian Sea, reaching the region of what is present-day Ukraine. Upon return, he established base on the shores of the Caspian Sea, after which he reportedly also sent an envoy named Gan Ying to Daqin (Rome). Ban Chao was created the Marquess of Dingyuan (定遠侯, i.e., "the Marquess who stabilized faraway places") for his services to the Han Empire and returned to the capital Loyang at the age of 70 years old and died there in the year 102. Following his death, the power of the Xiongnu in Western Territory increased again, and the Chinese were never again able to reach so far to the west.

Leadership struggle among the Xiongnu

As the Xiongnu empire expanded, it became clear that the original leadership structures lacked flexibility and could not maintain effective cohesion. The traditional succession of the eldest son became increasingly ineffective in meeting wartime emergencies in the 1st century B.C.E.. To combat the problems of succession, the Huhanye Shanyu (58 B.C.E.-31 B.C.E.) later laid down the rule that his heir apparent must pass the throne on to a younger brother. This pattern of fraternal succession did indeed become the norm.

The growth of regionalism became clear around this period, when local kings refused to attend the annual meetings at the shanyu's court. During this period, shanyu were forced to develop power bases in their own regions to secure the throne.

In the period 114 B.C.E. to 60 B.C.E., the Xiongnu produced altogether seven shanyu. Two of them, Chanshilu and Huyanti, assumed the office while still children. In 60 B.C.E., Tuqitang, the "Worthy Prince of the Right," became Wuyanjuti Shanyu. No sooner had he come to the throne, than he began to purge from power those whose base lay in the left group. Thus antagonised, in 58 B.C.E. the nobility of the left put forward Huhanye as their own shanyu. The year 57 B.C.E. saw a struggle for power among five regional groupings, each with its own shanyu. In 54 B.C.E. Huhanye abandoned his capital in the north after being defeated by his brother, the Zhizhi Shanyu.

Tributary relations with the Han

In 53 B.C.E. Huyanye (呼韓邪) decided to enter into tributary relations with Han China. The original terms insisted on by the Han court were that, first, the shanyu or his representatives should come to the capital to pay homage; secondly, the shanyu should send a hostage prince; and thirdly, the shanyu should present tribute to the Han emperor. The political status of the Xiongnu in the Chinese world order was reduced from that of a "brotherly state" to that of an "outer vassal" (外臣). During this period, however, the Xiongnu maintained political sovereignty and full territorial integrity. The Great Wall of China continued to serve as the line of demarcation between Han and Xiongnu.

Huyanye sent his son, the "wise king of the right" Shuloujutang, to the Han court as hostage. In 51 B.C.E. he personally visited Chang'an to pay homage to the emperor on the Chinese New Year. On the financial side, Huhanye was amply rewarded in large quantities of gold, cash, clothes, silk, horses and grain for his participation. Huhanye made two more homage trips, in 49 B.C.E. and 33 B.C.E.; with each one the imperial gifts were increased. On the last trip, Huhanye took the opportunity to ask to be allowed to become an imperial son-in-law. As a sign of the decline in the political status of the Xiongnu, Emperor Yuan refused, giving him instead five ladies-in-waiting. One of them was Wang Zhaojun, famed in Chinese folklore as one of the Four Beauties.

When Zhizhi learned of his brother's submission, he also sent a son to the Han court as hostage in 53 B.C.E. Then twice, in 51 B.C.E. and 50 B.C.E., he sent envoys to the Han court with tribute. But having failed to pay homage personally, he was never admitted to the tributary system. In 36 B.C.E., a junior officer named Chen Tang, with the help of Gan Yanshou, protector-general of the Western Regions, assembled an expeditionary force that defeated Zhizhi and sent his head as a trophy to Chang'an.

Tributary relations were discontinued during the reign of Huduershi (AD 18-48), corresponding to the political upheavals of the Xin Dynasty in China. The Xiongnu took the opportunity to regain control of the western regions, as well as neighbouring peoples such as the Wuhuan. In AD 24, Hudershi even talked about reversing the tributary system.

Late history

Northern Xiongnu

The Xiongnu's new power was met with a policy of appeasement by Emperor Guangwu. At the height of his power, Huduershi even compared himself to his illustrious ancestor, Modu. Due to growing regionalism among the Xiongnu, however, Huduershi was never able to establish unquestioned authority. When he designated his son as heir apparent (in contravention of the principle of fraternal succession established by Huhanye), Bi, the Rizhu king of the right, refused to attend the annual meeting at the shanyu's court.

As the eldest son of the preceding shanyu, Bi had a legitimate claim to the succession. In 48, two years after Huduershi's son Punu ascended the throne, eight Xiongnu tribes in Bi's powerbase in the south, with a military force totalling 40,000 to 50,000 men, acclaimed Bi as their own shanyu. Throughout the Eastern Han period, these two groups were called the southern Xiongnu and the northern Xiongnu, respectively.

Hard pressed by the northern Xiongnu and plagued by natural calamities, Bi brought the southern Xiongnu into tributary relations with Han China in 50. The tributary system was considerably tightened to keep the southern Xiongnu under Han supervision. The shanyu was ordered to establish his court in the Meiji district of Xihe commandery. The southern Xiongnu were resettled in eight frontier commanderies. At the same time, large numbers of Chinese were forced to migrate to these commanderies, where mixed settlements began to appear. The northern Xiongnu were dispersed by the Xianbei in 85 and again in 89 by the Chinese during the Battle of Ikh Bayan, of which the last Northern Shanyu was defeated and fled over to the north west with his subjects.

Southern Xiongnu

Economically, the southern Xiongnu relied almost totally on Han assistance. Tensions were evident between the settled Chinese and practitioners of the nomadic way of life. Thus, in 94 Anguo Shanyu joined forces with newly subjugated Xiongnu from the north and started a large scale rebellion against the Han.

Towards the end of the Eastern Han, the southern Xiongnu were drawn into the rebellions then plaguing the Han court. In 188, the shanyu was murdered by some of his own subjects for agreeing to send troops to help the Han suppress a rebellion in Hebei - many of the Xiongnu feared that it would set a precedent for unending military service to the Han court. The murdered shanyu's son succeeded him, but was then overthrown by the same rebellious faction in 189. He travelled to Luoyang (the Han capital) to seek aid from the Han court, but at this time the Han court was in disorder from the clash between Grand General He Jin and the eunuchs, and the intervention of the warlord Dong Zhuo. The shanyu named Yufuluo (於扶羅), but entitled Chizhisizhu (特至尸逐侯), had no choice but to settle down with his followers in Pingyang, a city in Shanxi. In 195, he died and was succeeded by his brother Hucuquan.

In 216, the warlord-statesman Cao Cao detained Hucuquan in the city of Ye, and divided his followers in Shanxi into five divisions: left, right, south, north, and centre. This was aimed at preventing the exiled Xiongnu in Shanxi from engaging in rebellion, and also allowed Cao Cao to use the Xiongnu as auxiliaries in his cavalry. Eventually, the Xiongnu aristocracy in Shanxi changed their surname from Luanti to Liu for prestige reasons, claiming that they were related to the Han imperial clan through the old intermarriage policy.

After the Han Dynasty

After Hucuquan, the Xiongnu were partitioned into five local tribes. The complicated ethnic situation of the mixed frontier settlements instituted during the Eastern Han had grave consequences, not fully apprehended by the Chinese government until the end of the 3rd century. By 260, Liu Qubei had organized the Tiefu confederacy in the north east, and by 290, Liu Yuan was leading a splinter group in the south west. At that time, non-Chinese unrest reached alarming proportions along the whole of the Western Jin frontier.

Liu Yuan's Northern Han (304-318)

In 304 the sinicised Liu Yuan, a grandson of Yufuluo Chizhisizhu stirred up descendants of the southern Xiongnu in rebellion in Shanxi, taking advantage of the War of the Eight Princes then raging around the Western Jin capital Luoyang. Under Liu Yuan's leadership, they were joined by a large number of frontier Chinese and became known as Bei Han. Liu Yuan used 'Han' as the name of his state, hoping to tap into the lingering nostalgia for the glory of the Han dynasty, and established his capital in Pingyang. The Xiongnu use of large numbers of heavy cavalry with iron armour for both rider and horse gave them a decisive advantage over Jin armies already weakened and demoralised by three years of civil war. In 311, they captured Luoyang, and with it the Jin emperor Sima Chi (Emperor Huai). In 316, the next Jin emperor was captured in Chang'an, and the whole of north China came under Xiongnu rule while remnants of the Jin dynasty survived in the south (known to historians as the Eastern Jin).

Liu Yao's Former Zhao (318-329)

In 318, after suppressing a coup by a powerful minister in the Xiongnu-Han court (in which the Xiongnu-Han emperor and a large proportion of the aristocracy were massacred), the Xiongnu prince Liu Yao moved the Xiongnu-Han capital from Pingyang to Chang'an and renamed the dynasty as Zhao (it is hence known to historians collectively as Han Zhao). However, the eastern part of north China came under the control of a rebel Xiongnu-Han general of Jie (probably Yeniseian) ancestry named Shi Le. Liu Yao and Shi Le fought a long war until 329, when Liu Yao was captured in battle and executed. Chang'an fell to Shi Le soon after, and the Xiongnu dynasty was wiped out. North China was ruled by Shi Le's Later Zhao dynasty for the next 20 years.

However, the "Liu" Xiongnu remained active in the north for at least another century.

Tiefu & Xia (260-431)

The northern Tiefu branch of the Xiongnu gained control of the Inner Mongolian region in the 10 years between the conquest of the Tuoba Xianbei state of Dai by the Former Qin empire in 376, and its restoration in 386 as the Northern Wei. After 386, the Tiefu were gradually destroyed by or surrendered to the Tuoba, with the submitting Tiefu becoming known as the Dugu. Liu Bobo, a surviving prince of the Tiefu fled to the Ordos Loop, where he founded a state called the Xia (thus named because of the Xiongnu's supposed ancestry from the Xia dynasty) and changed his surname to Helian (赫連). The Helian-Xia state was conquered by the Northern Wei in 428-431, and the Xiongnu thenceforth effectively ceased to play a major role in Chinese history, assimilating into the Xianbei and Han ethnicities.

Juqu & Northern Liang (401-460)

The Juqu were a branch of the Xiongnu, their leader Juqu Mengxun took over the Northern Liang by overthrew the former puppet ruler Duan Ye. By 439, the Juqu were destroyed by the Northern Wei, while the remnants of them would be settled in the Gaochang before being destroyed by the Rouran.

Archaeology

In the 1920s, Pyotr Kozlov's excavations of the royal tombs dated to about 1st century CE at Noin-Ula in northern Mongolia provided a glimpse into the lost world of the Xiongnu. Other archaeological sites have been unearthed in Inner Mongolia and elsewhere; they represent the neolithic and historical periods of the Xiongnu's history.[13] Those included the Ordos culture, many of them had been identified as the Xiongnu cultures, the region were occupied predominantly by Mongoloid known from their skeletal remains and artifacts.[14]

Did the Northern Xiongnu become the Huns?

| Etymology of 匈 Source: http://starling.rinet.ru | |

|---|---|

| Preclassic Old Chinese: | sŋoŋ |

| Classic Old Chinese: | ŋ̥oŋ |

| Postclassic Old Chinese: | hoŋ |

| Middle Chinese: | xöuŋ |

| Modern Cantonese: | hūng |

| Modern Mandarin: | xiōng |

| Modern Sino-Korean: | hyung |

As in the case of the Rouran with the Avars, oversimplifications have led to the Xiongnu often being identified with the Huns, who populated the frontiers of Europe. The connection started with the writings of the eighteenth century French historian de Guignes, who noticed that a few of the barbarian tribes north of China associated with the Xiongnu had been named "Hun" with varying Chinese characters. This theory remains at the level of speculation, although it is accepted by some scholars, including Chinese ones. DNA testing of Hun remains has not proven conclusive in determining the origin of the Huns.

Linguistically, it is important to understand that "xiōngnú" is only the modern standard Mandarin pronunciation (based on the Beijing dialect) of "匈奴." At the time of Hunnish contact with the world (the 4th–6th centuries AD), the sound of the character "匈" has been reconstructed as /hoŋ/.

The supposed sound of the first character has a clear similarity with the name "Hun" in European languages. Whether this is evidence of kinship or mere coincidence is hard to tell. It could lend credence to the theory that the Huns were in fact descendants of the Northern Xiongnu who migrated westward, or that the Huns were using a name borrowed from the Northern Xiongnu, or that these Xiongnu made up part of the Hun confederation.

The traditional etymology of "匈" is that it is as pictogram of the facial features of one of these people, wearing a helmet, with the "x" under the helmet representing the scars they inflicted on their faces to frighten their enemies. However, there is no actual evidence for this interpretation.

In modern Chinese, the character "匈" is used in four ways: to mean "chest" (written 胸 in this sense as the set of Chinese characters evolves), in the name 匈奴 Xiōngnú "Xiongnu," in the word 匈人 Xiōngrén "Hun [person]," and in the name 匈牙利 Xiōngyálì "Hungary." The last of these is a modern coinage which may derive from the belief that the Huns were related to the Xiongnu.[citation needed]

The second character, "奴," appears to have no parallel in Western terminology. Its contemporary pronunciation was /nhō/, and it means "slave," although it is possible that it has only a phonetic role in the name 匈奴. There is almost certainly no connection between the "chest" meaning of 匈 and its ethnic meaning. There might conceivably be some sort of connection with the identically pronounced word "凶," which means "fierce," "ferocious," "inauspicious," "bad," or "violent act." Most probably, the word derives from the tribe's own name for itself as a semi-phonetic transliteration into Chinese, and the character was chosen somewhat arbitrarily — a practice that continues today in Chinese renderings of foreign names.

Although the phonetic side of the question is not conclusive, new results from Central Asia might conduct to shift the balance in favor of a political and cultural link between the Xiongnu and the Huns. The Central Asian sources of the 4th century translated in both direction Xiongnu by Huns (in the Sogdian Ancient Letters, the Xiongnu in Northern China are named xwn, while in the Buddhist translations by Dharmarakhsa Huna of the Indian text is translated Xiongnu). Moreover, from an archaeological point of view, it is certain that the Hunnic cauldrons are similar to the Ordos Xiongnu ones. Moreover, they were used in the same rituals, as in Hungary and in the Ordos they were found buried in river banks.

Another clue in the link between the Xiongnu and the Huns is indicated by an old Byzantine codex dating back to 14th century. Inside the codex was a list in a Slav language from the early Middle Ages. This was decoded and translated by Omeljan Pritsak professor of history and language (at Lvov, Hamburg and Harvard University) in 1955 and named: "The Old-Bulgarian King List" [15] (Nominalia of the Bulgarian Khans). This contains the names and descendants of the Hun kings` dynasty. On the start of it is the great Mao-Tun (Modu shanyu), who established the Xiongnu Empire. Among the other descendants` names is the name of Ernakh, the youngest son of Attila The Hun. It indicates that the Xiongnu and the Huns lived under the same ruler dynasty. The possibility of Xiongnu eventually becoming the Huns is indicated by this codex.

See also

- Chinese people

- Wu Hu

- Huns

- Turkic peoples

- Battle of Mayi

- Battle of Ikh Bayan

- Noin-Ula

Notes

- ↑ Wang (2004). "Outlines of Ethnic Groups in China." p. 133.

- ↑ GENG Shi-min On Altaic Common Language and Xiongnu Language. (Wanfang Data: Digital Periodicals, 2005)

- ↑ Vovin, Alexander. "Did the Xiongnu speak a Yeniseian language?." Central Asiatic Journal 44/1 (2000), pp. 87-104.

- ↑ Keyser-Tracqui C., Crubezy E., Ludes B. Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analysis of a 2,000-year-old necropolis in the Egyin Gol Valley of Mongolia American Journal of Human Genetics 2003 August; 73(2): 247–260.

- ↑ The Gök Türk Empire All Empires

- ↑ Nancy Touchette Ancient DNA Tells Tales from the Grave "Skeletons from the most recent graves also contained DNA sequences similar to those in people from present-day Turkey. This supports other studies indicating that Turkic tribes originated at least in part in Mongolia at the end of the Xiongnu period."

- ↑ Paola Demattè Writing the Landscape: the Petroglyphs of Inner Mongolia and Ningxia Province (China). (Paper presented at the First International Conference of Eurasian Archaeology, University of Chicago, May 3-4, 2002.)

- ↑ MA Li-qing On the new evidence on Xiongnu's writings. (Wanfang Data: Digital Periodicals, 2004)

- ↑ Barfield, Thomas. The Perilous Frontier (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989).

- ↑ Di Cosmo, "The Northern Frontier in Pre-Imperial China," in The Cambridge History of Ancient China, edited by Michael Loewe and Edward Shaughnessy, pp. 885-966. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- ↑ These campaigns are described in detail by Michael Loewe, "The campaigns of Han Wu-ti," in Chinese ways in warfare, ed. Frank A. Kierman, Jr., and John K. Fairbank (Cambridge, Mass., 1974).

- ↑ This view was put forward to Wang Mang in AD 14: Han Shu (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju edition) 94B, p. 3824.

- ↑ Zhang et al (2001). "Cultural History of Ancient Northern Ethnic Groups in China," p. 176-225.

- ↑ Ma, Liqing (2005). Original Xiongnu, An Archaeological Explore on the Xiongnu's History and Culture. Hohhot: Inner Mongolia University Press. ISBN 7-81074-796-7, p. 196-197

- ↑ Pritsak, Omeljan: Die bulgarische Fürstenliste und die Sprache der Protobulgaren. 1955. Wiesbaden.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Primary sources

- Ban Gu (班固), Han shu (漢書). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1962.

- Fan Ye (范曄) et al., comp. Hou Han shu (後漢書). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1965.

- Sima Qian (司馬遷) et al., Shi ji (史記). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1959.

Secondary sources

- de Crespigny, Rafe. Northern frontier: The policies and strategies of the Later Han empire. Asian Studies Monographs, New Series No. 4, Faculty of Asian Studies. Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1984. ISBN 0-86784-410-8. See[1] for chapter 1 The Government and Geography of the Northern Frontier of Later Han. (Internet publication April 2004. This version includes a general map and some summary annotations but no characters or detailed notes).

- de Crespigny, Rafe. The Division and Destruction of the Xiongnu Confederacy in the first and second centuries AD, [Turkish: "Hun Konfederasyonu'nun Blnmesi ve Yikilmasi"], being a paper published in The Turks [Yeni TrkiyeMedya Hismetleri-Murat Ocak], Ankara 2002, 256-243 & 749-757. [2](Internet publication April 2004. This version includes a map and notes but no characters).

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu. Draft annotated English translation.[3]

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 C.E. Draft annotated English translation. [4]

- Hulsewé, A. F. P. and Loewe, M. A. N. 1979. China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 B.C.E. – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. E. J. Brill, Leiden, 1979. ISBN 90-04-05884-2.

- Ma, Liqing (2005). Original Xiongnu, An Archaeological Explore on the Xiongnu's History and Culture. Hohhot: Inner Mongolia University Press. ISBN 7-81074-796-7.

- Zhang, Bibo and Dong, Guoyao (2001). "Cultural History of Ancient Northern Ethnic Groups in China." Harbin: Heilongjiang People's Press. ISBN 7-207-03325-7.

- Wang, Zhonghan (2004). "Outlines of Ethnic Groups in China." Taiyuan: Shanxi Education Press. ISBN 7-5440-2660-4.

- Yü Ying-shih, "Han foreign relations," Cambridge History of China: volume 1, The Ch'in and Han empires 221 B.C.E. – A.D. 220 Cambridge University Press, Cambridge [etc.], 1986, pp. 377-462. ISBN 0-521-24327-0.

- Vovin, Alexander. "Did the Xiongnu speak a Yeniseian language?." Central Asiatic Journal 44/1 (2000), pp. 87-104.

- de la Vaissière, E., "Huns et Xiongnu." Central Asiatic Journal 49/1 (2005), pp. 3-26.

zh-classical:匈奴

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.