Difference between revisions of "Timurid Dynasty" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (55 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ready}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{copyedited}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | }} | ||

| − | The '''Timurids''' | + | [[Image:Timurid Dynasty 821 - 873 (AD).PNG|thumb|Timurid Dynasty at its greatest extent.]] |

| + | |||

| + | The '''Timurids,''' self-designated ''Gurkānī''<ref name="Columbia">The Columbia Encyclopedia, [http://www.bartleby.com/65/ti/Timurids.html Timurids.] Retrieved October 23, 2008.</ref> descent, whose empire included the whole of Central Asia, [[Iran]], modern [[Afghanistan]], and [[Pakistan]], as well as large parts of [[India]], [[Mesopotamia]], and [[Caucasus]]. It was founded by the legendary conqueror [[Timur]] ''(Tamerlane)'' in the fourteenth century. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the sixteenth century, Timurid prince [[Babur]], the ruler of Ferghana, invaded India and founded the [[Mughal Empire]], which ruled most of the Indian subcontinent until its decline after [[Aurangzeb]] in the early eighteenth century, and its eventual demise by the [[British Raj]] after the [[First War of Indian Independence|Indian rebellion of 1857]]. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | After establishing their rule in India, the Timurids became great patrons of [[culture]] They gave the world one of its most beautiful feats of architecture, the [[Taj Mahal]], and fused Persian and India styles to produce new art-forms, and a new language, Urdu. At times, followers of different [[faith|faiths]] under Timurid rule enjoyed [[religious freedom]] and non-Muslims held senior posts in the Timurid administration. The positive aspect of their legacy still contributes to [[Interfaith relations|interfaith harmony]] in India, [[Pakistan]], and [[Bangladesh]], but the negative aspect fuels inter-community (communitarian) hatred and even violence. Lessons can be learned from the legacy of Timurid rule on how to govern multi-racial, multi-religious societies. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Origins == | == Origins == | ||

| − | + | The origin of the Timurid dynasty goes back to the [[Mongols|Mongolian]] nomadic confederation known as Barlas, who were remnants of the original Mongol army of [[Genghis Khan]]. After the Mongol conquest of Central Asia, the Barlas settled in [[Turkistan]] (which then became also known as ''Moghulistan''--"Land of Mongols") and intermingled to a considerable degree with the local Turkic and Turkic-speaking population, so that at the time of Timur's reign the Barlas had become thoroughly Turkicized in terms of language and habits. Additionally, by adopting [[Islam]], the Central Asian Turks and Mongols also adopted the Persian literary and high culture which has dominated Central Asia since the early days of Islamic influence. Persian literature was instrumental in the assimilation of the Timurid elite to the Perso-Islamic courtly culture.<ref>Roxburgh (2005), 130.</ref> Timur was also steeped in Persian culture<ref>Chaliand and Berrett (2004), 75.</ref> and in most of the territories which he incorporated, Persian was the primary language of administration and literary culture. Thus the language of the settled "diwan" was Persian, and its scribes had to be thoroughly adept in Persian culture, whatever their ethnic origin.<ref>Manz (1989), 109.</ref> | |

| − | The origin of the Timurid dynasty goes back to the [[Mongols|Mongolian]] nomadic confederation known as | ||

== Founding the dynasty == | == Founding the dynasty == | ||

| − | + | Timur conquered large parts of Transoxiana (in modern day Central Asia) and Khorasan (parts of modern day [[Iran]], [[Afghanistan]], [[Uzbekistan]], [[Tajikistan]], and [[Turkmenistan]]) from 1363 onwards with various alliances (Samarkand in 1366, and Balkh in 1369), and was recognized as ruler over them in 1370. Acting officially in the name of the Mongolian Chagatai ulus, he subjugated Transoxania and Khwarazm in the years that followed and began a campaign westwards in 1380. By 1389 he had removed the Kartids from Herat and advanced into mainland [[Persian Empire|Persia]] from 1382 (capture of [[Isfahan]] in 1387, removal of the [[Muzaffarids]] from Shiraz in 1393, and expulsion of the Jalayirids from [[Baghdad]]). In 1394/95, he triumphed over the [[Golden Horde]] and enforced his sovereignty in the [[Caucasus]], in 1398 subjugated Multan and Dipalpur in modern day [[Pakistan]] and in modern day India left [[Delhi]] in such ruin that it is said for two months "not a bird moved wing in the city."<ref>Marozzi (2006), 274.</ref> | |

| − | Timur conquered large parts of | + | In 1400/01, conquered [[Aleppo]], [[Damascus]] and eastern [[Anatolia]], in 1401, destroyed Baghdad and in 1402, triumphed over the Ottomans at [[Ankara]]. In addition, he transformed Samarkand into the ''Center of the World''. An estimated 17 million people may have died from his conquests.<ref>Matthew White, [http://users.erols.com/mwhite28/warstat0.htm#Timur Selected Death Tolls: Timur Lenk (1369–1405),] Historical Atlas of the 20th Century. Retrieved October 23, 2008.</ref> |

| − | In 1400/01 conquered [[Aleppo]], [[Damascus]] and eastern [[Anatolia]], in 1401 destroyed Baghdad and in 1402 triumphed over the Ottomans at [[Ankara]]. In addition, he transformed | ||

| − | After the end of the Timurid Empire in 1506, the | + | After the end of the Timurid Empire in 1506, the Mughal Empire was later established in India by [[Babur]] in 1526, who was a descendant of Timur through his father and possibly a descendant of [[Genghis Khan]] through his mother. The dynasty he established is commonly known as the Mughal Dynasty. By the seventeenth century, the Mughal Empire ruled most of India, but later declined during the eighteenth century. The Timurid Dynasty came to an end in 1857 after the Mughal Empire was dissolved by the [[British Empire]] and [[Bahadur Shah II]] was exiled to [[Burma]]. |

| − | Due to the fact that the Persian cities were desolated by previous wars, the seat of Persian culture was now in Samarkand and Herat. | + | Due to the fact that the Persian cities were desolated by previous wars, the seat of Persian culture was now in Samarkand and Herat. These cities became the center of the Timurid renaissance<ref name="Columbia"/> |

== Culture == | == Culture == | ||

| − | Although the Timurids hailed from the | + | Although the Timurids hailed from the Barlas tribe which was of Mongol origin, they had embraced Persian [[culture]]<ref name="Iranica">F. Lehmann, [http://www.iranica.com/newsite/search/searchpdf.isc?ReqStrPDFPath=/home/iranica/public_html/newsite/pdfarticles/v3_articles/babor_zahir-al-din_mohammad&OptStrLogFile=/home/iranica/public_html/newsite/logs/pdfdownload.html Zaher ud-Din Babor - Founder of Mughal empire,] ''Encyclopaedia Iranica.''</ref> and Persian art (distinguished by extensive adaptations from the [[China|Chinese]],<ref name="Columbia"/> and also Chagatay Literature,<ref name="Columbia"/> converted to [[Islam]] and resided in Turkestan and Khorasan. Thus, the Timurid era had a dual character,<ref name="Columbia"/> which reflected both the Turco-Mongol origins and the Persian culture as well the Persian language. The Persian language was also the state language (also known as Diwan language) of the dynasty. |

| − | |||

===Literature=== | ===Literature=== | ||

| − | ==== Timurid | + | ==== Timurid literature in Persian language ==== |

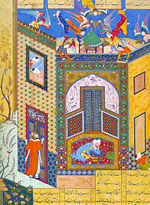

| − | [[Image:Jami Rose Garden.jpg|right|150px|thumb|Illustration from | + | [[Image:Jami Rose Garden.jpg|right|150px|thumb|Illustration from Jāmī's ''Rose Garden of the Pious,'' dated 1553. The image blends Persian [[poetry]] and Persian miniature into one, as is the norm for many works of the Timurid era.]] |

| − | Persian literature, especially Persian poetry occupied | + | Persian literature, especially Persian poetry occupied a central place in the process of assimilation of the Timurid elite to the Perso-Islamic courtly culture.<ref>Roxburgh (2005), 130.</ref> The Timurid sultans, especially Šāhru<u>kh</u> Mīrzā and his son Mohammad Taragai Oloğ Beg, patronized Persian culture. Among the most important literary works of the Timurid era is the Persian biography of Timur, known as ''"Zafarnāma,"'' written by Sharaf ud-Dīn Alī Yazdī, which itself is based on an older ''"Zafarnāma"'' by Nizām al-Dīn Shāmī, the official biographer of Timur during his lifetime. The most famous poet of the Timurid era was Nūr ud-Dīn Jāmī, the last great medieval [[Sufi]] [[mysticism|mystic]] of Persia and one of the greatest in Persian poetry. The most famous painter of the Timurid court, as well as the most famous of the Persian miniature painters in general, was [[Behzad|Ustād Kamāl ud-Dīin Behzād]]. In addition, the Timurid sultan [[Ulugh Beg]] is known as a great [[asrronomy|astronomer]], building a "observatory that was a marvel of the age."<ref>Lewis Macleod, [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/world/monitoring/media_reports/948757.stm Uzbekistan restores Timurid legacy,] BBC. Retrieved October 23, 2008.</ref> Daniel says that the Timurid's were "distinguished as patrons of Islamic scholarship, literature, [[art]]] and [[architecture]]" and that several Timurid rulers were 'accomplished in these fields themselves."<ref>Daniel (2001), 81-82.</ref> |

| + | |||

=====BaySanghur Shahnameh===== | =====BaySanghur Shahnameh===== | ||

| − | Baysanghur commissioned a new edition of the | + | Baysanghur commissioned a new edition of the ''Shahnameh'' of [[Ferdowsi]] and wrote an introduction to it. According to T. Lenz:<ref>T. Lenz, [http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/v4f1/v4f1a008.html Baysonghori Shahnameh,] ''Encyclopedia Iranica.'' Retrieved October 23, 2008.</ref><blockquote>It can be viewed as a specific reaction in the wake of Timur's death in 807/1405 to the new cultural demands facing Shahhrokh and his sons, a Turkic military elite no longer deriving their power and influence solely from a charismatic steppe leader with a carefully cultivated linkage to Mongol aristocracy. Now centered in Khorasan, the ruling house regarded the increased assimilation and patronage of Persian culture as an integral component of efforts to secure the legitimacy and authority of the dynasty within the context of the Islamic Iranian monarchical tradition, and the Baysanghur Shahnameh, as much a precious object as it is a manuscript to be read, powerfully symbolizes the Timurid conception of their own place in that tradition. A valuable documentary source for Timurid decorative arts that have all but disappeared for the period, the manuscript still awaits a comprehensive monographic study.</blockquote> |

| − | ==== National | + | ==== National literature in Chagatay language ==== |

| − | The early Timurids played a very important role in the history of | + | The early Timurids played a very important role in the history of Turkic literature. Based on the established Persian literary tradition, a national Turkic literature was developed, written in the Chagatay language, the native tongue of the Timurid family. Chagatay poets such as Mīr Alī Sher Nawā'ī, Sultan Husayn Bāyqarā, and Babur encouraged other Turkic-speaking poets to write in their own vernacular in addition to Arabic and Persian. |

| − | The | + | The ''Bāburnāma,'' the autobiography of Bābur, as well as Mīr Alī Sher Nawā'ī's Chagatay poetry are among the best-known Turkic literary works and have fascinated and influenced many others world wide. The Baburnama was highly Persianized in its sentence structure, morphology or word formation and vocabulary.<ref>Dale (2004), 150.</ref> |

=== Art=== | === Art=== | ||

| − | During the reign of Timurid rule, the golden age of Persian painting was ushered. | + | During the reign of Timurid rule, the golden age of Persian painting was ushered. During this period as well as the [[Safavid Empire|Safavid]] dynasty, Chinese art and artists had a significant influence on Persian art. Timurid artists refined the Persian art of the book, which combines paper, calligraphy, illumination, illustration and binding in a brilliant and colorful whole.<ref>Onians (2004), 132.</ref> It was the Mongol [[ethnicity]] of the Chaghatayid and Timurid Khans that is the source of the stylistic depiction Persian art during the [[Middle Ages]]. These same Mongols intermarried with the Persians and Turks]] of Central Asia, even adopting their religion and languages. Yet their simple control of the world at that time, particularly in the thirteenth-fifteenth centuries, reflected itself in the idealized appearance of Persians as Mongols. Though the ethnic make-up gradually blended into the Iranian and [[Mesopotamia]]n local populations, the Mongol stylism continued well after, and crossed into Asia Minor and even North [[Africa]]. |

===Architecture=== | ===Architecture=== | ||

====Timurid architecture==== | ====Timurid architecture==== | ||

| − | [[Image:Akhangan.jpg|thumb|right|150px|''"Akhangan" tomb'' | + | |

| − | + | [[Image:Akhangan.jpg|thumb|right|150px|''"Akhangan" tomb,'' where Gowharšād's sister Gowhartāj is buried. The architecture is a fine example of the Timurid era in Persia.]] | |

| − | In the realm of architecture, the Timurids drew on and developed many [[Seljuq]] traditions. Turquoise and blue tiles forming intricate linear and geometric patterns decorated the facades of buildings. Sometimes the interior was decorated similarly, with painting and stucco relief further enriching the effect. | + | |

| + | In the realm of architecture, the Timurids drew on and developed many [[Seljuq dynasty|Seljuq]] traditions. Turquoise and blue tiles forming intricate linear and geometric patterns decorated the facades of buildings. Sometimes the interior was decorated similarly, with painting and stucco relief further enriching the effect. Timurid architecture is the pinnacle of Islamic art in [[Central Asia]]. Spectacular and stately edifices erected by Timur and his successors in Samarkand and Herat helped to disseminate the influence of the Ilkhanid school of art in India, thus giving rise to the celebrated ''Mughal'' (or ''Mongol'') school of architecture. Timurid architecture started with the sanctuary of Ahmed Yasawi in present-day [[Kazakhstan]] and culminated in Timur's mausoleum Gur-e Amir in Samarkand. Timur’s Gur-I Mir, the fourteenth century mausoleum of the conqueror is covered with "turquoise Persian tiles."<ref name=Norwich278>Norwich (1975), 278.</ref> Nearby, in the center of the ancient town, there is a ''Persian style Madrassa (religious school)''<ref name=Norwich278/> and a ''Persian style Mosque''<ref name=Norwich278/> built by [[Ulugh Beg]]. The mausoleum of Timurid princes, with their turquoise and blue-tiled domes remain among the most refined and exquisite ''Persian architecture.''<ref>Kennedy (2007), 237.</ref> Axial symmetry is a characteristic of all major Timurid structures, notably the Shāh-e Zenda in [[Samarkand]], the ''Musallah'' complex in Herat, and the mosque of Gowhar Shād in Mashhad. Double domes of various shapes abound, and the outsides are perfused with brilliantly colors. Timurs dominance of the region strengthened the influence of his capital and Persian architecture upon India.<ref>Fletcher and Cruickshan (1996), 606.</ref> | ||

====Mughal architecture==== | ====Mughal architecture==== | ||

| − | + | After the foundation of the Mughal Empire, the Timurids successfully expanded the Persian cultural influence from Khorasan to [[India]], where the Persian language, [[literature]], [[architecture]], and [[art]] dominated the Indian subcontinent]] until the [[British Raj|British conquest]]. The Mughals, Persianized Turks who invaded from Central Asia and claimed descent from both Timur and Genghis—strengthened the Persianate culture of Muslim India.<ref>Canfield (1991), 20.</ref> | |

| − | + | The Mughal period marked a striking revival of Islamic architecture in northern India. Under the patronage of the Mughal emperors, Indian, Persian, and various provincial styles were fused to produce works of unusual quality and refinement. | |

| − | The Mughal | + | The Mughal emperor [[Akbar the Great]] constructed the royal city of [[Fatehpur Sikri]], located 26 miles west of [[Agra]], in the late 1500s. The most famous example of Mughal architecture is the Taj Mahal, the "teardrop on eternity," completed in 1648 by the emperor [[Shah Jahan]] in memory of his wife [[Mumtaz Mahal]] who died while giving birth to their 14th child. The extensive use of precious and semiprecious stones as inlay and the vast quantity of white marble required nearly bankrupted the empire. The Taj Mahal is completely symmetric other than the [[sarcophagus]] of Shah Jahan which is placed off center in the crypt room below the main floor. This symmetry extended to the building of an entire mirror mosque in red sandstone to complement the Mecca-facing mosque place to the west of the main structure. Another structure built that showed great depth of Mughal influence was the Shalimar Gardens. |

| − | + | ====Religion==== | |

| + | As Muslims, the Timurid rulers did much to promote Islam, building mosques and sponsoring scholarship. However, Muslims were always a minority within the Mughal Empire. Non-Muslims were at times treated harshly; both Babur and Aurangzeb destroyed Temples. Akbar, however, fused [[Christianity]], [[Hinduism]] and Islam into a single God-centered religion, Din-i-Ilahi. At other times, their rule was marked by a high degree of [[freedom of religion|religious tolerance]] when non-Muslims held high positions of state, no tithe was levied on non-Muslims and many people participated in religious festivals of traditions other than their own. Without denying that persecution of non-Muslims did occur under Timurid rule, Dutt says that "many Hindu and Muslim scholars studied each other's religions, while the common people existed [[peace|peacefully]]."<ref>Dutt (2006), 76.</ref> Many Timurid rulers were advocates of the [[Sufism|Sufu]] doctrine of ''wahdat-al-wajud,'' the "unity of [[God]] and the created world, which was given creative expression by a new breed of poets."<ref>Chandra (1999), 14.</ref> | ||

| − | == | + | ==Legacy== |

| − | + | Life under Timurid rule was for much of the time [[politics|politically]] stable, with many citizens enjoying peace and prosperity within secure borders. Perhaps the Timurids greatest achievement was their fusing of Persian and Indian forms, as Dutt comments, "the fusion of two cultures gave rise to new styles of art, architecture and music and to a new language, Urdu."<ref>Dutt (2006), 76.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The positive aspects of the Timurid legacy still contributes to [[Interfaith relations|interfaith harmony]] in India, [[Pakistan]] and [[Bangladesh]], but the negative aspect fuels inter-community (communitarian) hatred and even violence. Lessons can be learned from the legacy of Timurid rule on how to govern multi-racial, multi-religious societies. | |

| − | + | ===Rulers of the Timurid Empire=== | |

| − | * | + | * Timur (Tamerlane) 1370-1405 (771-807 AH)—with Suyur<u>gh</u>itmiš Chaghtay as nominal overlord followed by Mahmūd Chaghtay as overlord and finally Muhammad Sultān as heir |

| − | + | * Pir Muhammad bin Jahāngīr 1405-1407 (807-808 AH) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ===Rulers of | + | ====Rulers of Herat==== |

| + | * Shāhru<u>kh</u> 1405-1447 (807-50 AH) (overall ruler of the Timurid Empire 1409-1447) | ||

| + | * Abu'l-Qasim Bābar 1447-1457 (850-61 AH) | ||

| + | * Shāh Mahmūd 1457 (861 AH) | ||

| + | * Ibrāhim 1457-1459 (861-863 AH) | ||

| + | * Sultān Abu Sa’id Gūrgān 1459-1469 (863-73 AH) (in Transoxiana 1451-1469) | ||

| + | * Yādgār Muhammad 1470 (873 AH) | ||

| + | * Sultān Hussayn 1470-1506 (874-911 AH) | ||

| + | * Badi ul-Zamān 1506-1507 (911-912 AH) | ||

| + | * Muzaffar Hussayn 1506-1507 (911-912 AH) | ||

| + | ''Herat is conquered by the Uzbeks under Muhammad Shaybani'' | ||

| − | * | + | ====Rulers of Samarkand==== |

| − | * | + | * <u>Kh</u>alīl Sultān 1405-1409 (807-11 AH) |

| − | * | + | * Mohammad Taragai bin Shāhru<u>kh</u>-I 1409-1449 (811-53 AH) (overall ruler of the Timurid Empire 1447-1449) |

| − | * | + | * 'Abd al-Latif 1449-1450 (853-854 AH) |

| − | * | + | * ‘Abdullah 1450-1451 (854-55 AH) |

| + | * Sultān Abu Sa’id Gūrgān 1451-1469 (855-73 AH) (in Herat 1459-1469) | ||

''Abu Sa'id's sons divided his territories upon his death, into Samarkand, Badakhshan and Farghana'' | ''Abu Sa'id's sons divided his territories upon his death, into Samarkand, Badakhshan and Farghana'' | ||

| − | * | + | * Sultān ibn Abu Sa’id 1469-1494 (873-899 AH) |

| − | * | + | * Sultān Mahmūd ibn Abu Sa’id 1494-1495 (899-900 AH) |

| − | *Sultān Baysunqur 1495 - 1497 (900-902 AH) | + | * Sultān Baysunqur 1495-1497 (900-902 AH) |

| − | *Mas’ūd 1495 (900 AH) | + | * Mas’ūd 1495 (900 AH) |

| − | *Sultān Alī Mīrzā 1495 - 1500 (900-905 AH) | + | * Sultān Alī Mīrzā 1495-1500 (900-905 AH) |

| − | ''Samarkand is conquered by the | + | ''Samarkand is conquered by the Uzbeks under Muhammad Shaybani'' |

| − | == | + | ====Rulers of Mughal Empire==== |

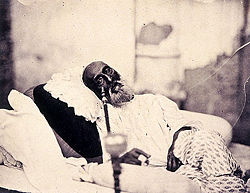

| + | [[Image:Bahadur Shah Zafar.jpg|thumb|250px|A photo of Bahadur Shah II in 1858, possibly the only picture ever taken of a Timurid king.]] | ||

| − | * | + | * Zahiruddin Babur Mirza 1526-1530 (933-937 AH)--established Mughal Dynasty in India (Mughal Empire) |

| − | + | * Nasiruddin Humayun Mirza 1530-1556 (937-963 AH)--ruler of Mughal Empire, son of Babur | |

| − | + | * Kamran Mirza 1530-1557 (937-962 AH)--ruler of Kabul and Lahore, son of Babur | |

| − | + | * [[Akbar the Great|Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar Mirza]] (Akbar the Great) 1556-1605 (963-1014 AH)--greatest ruler of Mughal Empire, son of Humayun | |

| − | + | * Abul Qasim Muhammad bin Kamran 968 AH | |

| − | + | * Suleiman Mirza 936-92 AH | |

| − | + | * Shahrukh III 983-87 AH--son of Ibrahim | |

| − | + | * [[Jahangir|Nuruddin Muhammad Jahangir]] 1605-1627 (1014-1036 AH)--ruler of [[Mughal Empire]], son of Akbar and [[Rajput]] Princess [[Jodhabai|Mariam Zamani]] | |

| − | + | * [[Shah Jahan|Shahbuddin Muhammad Shah Jahan]] (Shah Jahan I) 1627-1658--ruler of [[Mughal Empire]], son of Jahangir and Rajput [[Princess Manmati]] | |

| − | + | * [[Aurangzeb|Mohiuddin Mohammed Aurangzeb]] (Aurangzeb Alamgir I) 1658-1707--ruler of [[Mughal Empire]], son of Shah Jahan | |

| − | + | * [[Bahadur Shah I]] (Shah Alam I) 1707-1712--son of Aurangzeb | |

| − | + | * Jahandar Shah]], b. 1664, ruler from 1712-1713 | |

| − | + | * Furrukhsiyar, b. 1683, ruler from 1713-1719 | |

| − | + | * Rafi Ul-Darjat, ruler 1719 | |

| − | + | * Rafi Ud-Daulat ([[Shah Jahan II]]), ruler 1719 | |

| − | + | * Nikusiyar, ruler 1719 | |

| − | + | * Muhammad Ibrahim, ruler 1720 | |

| − | + | * Muhammad Shah, b. 1702, ruler from 1719–1720, 1720-1748 | |

| − | + | * Ahmad Shah Bahadur, b. 1725, ruler from 1748-1754 | |

| − | + | * [[Alamgir II]], b. 1699, ruler from 1754-1759==son of Jahandar Shah | |

| − | * | + | * [[Shah Jahan III]], ruler 1759 |

| − | * | + | * [[Shah Alam II]], b. 1728, ruler from 1759-1806 |

| − | *[[Akbar|Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar Mirza]] (Akbar the Great) 1556-1605 (963-1014 AH) - greatest ruler of | + | * [[Akbar Shah II]], b. 1760, ruler from 1806-1837 |

| − | *Abul Qasim Muhammad bin Kamran 968 AH | + | * [[Bahadur Shah II]] (Bahadur Shah Zafar) 1837-1857--last ruler of the Timurid Dynasty |

| − | *Suleiman Mirza 936-92 AH | ||

| − | *Shahrukh III 983-87 AH - son of Ibrahim | ||

| − | *[[Jahangir|Nuruddin Muhammad Jahangir]] 1605 - 1627 (1014-1036 AH) - ruler of [[Mughal Empire]], son of Akbar and [[Rajput]] Princess [[Jodhabai|Mariam Zamani]] | ||

| − | *[[Shah Jahan|Shahbuddin Muhammad Shah Jahan]] (Shah Jahan I) 1627 - 1658 - ruler of [[Mughal Empire]], son of Jahangir and Rajput [[Princess Manmati]] | ||

| − | *[[Aurangzeb|Mohiuddin Mohammed Aurangzeb]] (Aurangzeb Alamgir I) 1658-1707 - ruler of [[Mughal Empire]], son of Shah Jahan | ||

| − | *[[Bahadur Shah I]] (Shah Alam I) 1707 - 1712 - son of Aurangzeb | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | *[[Alamgir II]], b. 1699, ruler from 1754-1759 | ||

| − | *[[Shah Jahan III]], ruler 1759 | ||

| − | *[[Shah Alam II]], b. 1728, ruler from 1759-1806 | ||

| − | *[[Akbar Shah II]], b. 1760, ruler from 1806-1837 | ||

| − | *[[Bahadur Shah II]] (Bahadur Shah Zafar) 1837-1857 - last ruler of the Timurid Dynasty | ||

==Heads of the Timurid Dynasty== | ==Heads of the Timurid Dynasty== | ||

| + | *Bahadur Shah II (1857–1862) | ||

| + | *Shahzada Muhammad Hidayat Afshar, Ilahi Bakhsh Bahadur]] (1862–1878) | ||

| + | *Shahzada Muhammad Sulaiman Shah Bahadur (1878–1890) | ||

| + | *Shahzada Muhammad Kaiwan Shah Gorkwani, Suraya Jah Bahadur (1890–1913) | ||

| + | Mirza Salim Muhammad Shah Bahadur]] (1913–1925) | ||

| + | *No recognized head of the family (1925–1931) | ||

| + | Shahzada Muhammad Khair ud-din Mirza, Khurshid Jah Bahadur (1931–1975) | ||

| + | *Mirza Ghulam Moinuddin Muhammad, Javaid Jah Bahadur (1975-Present) | ||

| − | + | == Notes == | |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == References | + | ==References== |

| − | + | * Canfield, Robert Leroy. 1991. ''Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective.'' School of American Research advanced seminar series. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521390941. | |

| − | + | * Chaliand, Gérard, and A.M. Berrett. 2004. ''Nomadic Empires: From Mongolia to the Danube.'' New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9780765802040. | |

| − | + | *Chandra, Satish. 1999. ''Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals.'' New Delhi, IN: Har-Anand Publications. ISBN 9788124105221. | |

| − | * | + | * Dale, Stephen Frederic. 2004. ''The Garden of the Eight Paradises: Bābur and the Culture of Empire in Central Asia, Afghanistan and India (1483-1530).'' Brill's Inner Asian library, v. 10. Leiden, NL: Brill. ISBN 9789004137073. |

| − | * Chaliand, Gérard, and A. M. Berrett. 2004. ''Nomadic | + | * Daniel, Elton L. 2001. ''The History of Iran.'' The Greenwood histories of the modern nations. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313307317. |

| − | * Manz, Beatrice Forbes. 1989. ''The | + | * Dutt, Sagarika. 2006. ''India in a Globalized World.'' Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719069000. |

| − | * | + | * Fletcher, Banister, and Dan Cruickshank. 1996. ''Sir Banister Fletcher's A History of Architecture.'' London, UK: Architectural Press. ISBN 9780750622677. |

| + | * Kennedy, Hugh. 2007. ''The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World we Live in.'' Philadelphia, PA: Da Capo. ISBN 9780306815850. | ||

| + | * Manz, Beatrice Forbes. 1989. ''The Rise and Rule of Tamerlane.'' Cambridge studies in Islamic civilization. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521345958. | ||

| + | * Marozzi, Justin. 2006. ''Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, Conqueror of the World.'' Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 9780306814655. | ||

| + | * Norwich, John Julius. 1975. ''Great Architecture of the World.'' New York, NY: Random House. ISBN 9780394498874. | ||

| + | * Onians, John, and Oxford University Press. 2004. ''Atlas of World Art.'' Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195215830. | ||

| + | * Roxburgh, David J. 2005. ''The Persian Album, 1400-1600: From Dispersal to Collection.'' New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300103250. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved April 30, 2023. | ||

| + | *[http://www.art-arena.com/timurid.htm The Timurids]. | ||

| + | *[http://pagesperso-orange.fr/steppeasia/genealogie_tamerlan.htm Timurid genealogy]. | ||

| − | + | [[Category:History]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credit|241651078}} | {{Credit|241651078}} | ||

Latest revision as of 23:37, 30 April 2023

The Timurids, self-designated Gurkānī[1] descent, whose empire included the whole of Central Asia, Iran, modern Afghanistan, and Pakistan, as well as large parts of India, Mesopotamia, and Caucasus. It was founded by the legendary conqueror Timur (Tamerlane) in the fourteenth century.

In the sixteenth century, Timurid prince Babur, the ruler of Ferghana, invaded India and founded the Mughal Empire, which ruled most of the Indian subcontinent until its decline after Aurangzeb in the early eighteenth century, and its eventual demise by the British Raj after the Indian rebellion of 1857.

After establishing their rule in India, the Timurids became great patrons of culture They gave the world one of its most beautiful feats of architecture, the Taj Mahal, and fused Persian and India styles to produce new art-forms, and a new language, Urdu. At times, followers of different faiths under Timurid rule enjoyed religious freedom and non-Muslims held senior posts in the Timurid administration. The positive aspect of their legacy still contributes to interfaith harmony in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, but the negative aspect fuels inter-community (communitarian) hatred and even violence. Lessons can be learned from the legacy of Timurid rule on how to govern multi-racial, multi-religious societies.

Origins

The origin of the Timurid dynasty goes back to the Mongolian nomadic confederation known as Barlas, who were remnants of the original Mongol army of Genghis Khan. After the Mongol conquest of Central Asia, the Barlas settled in Turkistan (which then became also known as Moghulistan—"Land of Mongols") and intermingled to a considerable degree with the local Turkic and Turkic-speaking population, so that at the time of Timur's reign the Barlas had become thoroughly Turkicized in terms of language and habits. Additionally, by adopting Islam, the Central Asian Turks and Mongols also adopted the Persian literary and high culture which has dominated Central Asia since the early days of Islamic influence. Persian literature was instrumental in the assimilation of the Timurid elite to the Perso-Islamic courtly culture.[2] Timur was also steeped in Persian culture[3] and in most of the territories which he incorporated, Persian was the primary language of administration and literary culture. Thus the language of the settled "diwan" was Persian, and its scribes had to be thoroughly adept in Persian culture, whatever their ethnic origin.[4]

Founding the dynasty

Timur conquered large parts of Transoxiana (in modern day Central Asia) and Khorasan (parts of modern day Iran, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan) from 1363 onwards with various alliances (Samarkand in 1366, and Balkh in 1369), and was recognized as ruler over them in 1370. Acting officially in the name of the Mongolian Chagatai ulus, he subjugated Transoxania and Khwarazm in the years that followed and began a campaign westwards in 1380. By 1389 he had removed the Kartids from Herat and advanced into mainland Persia from 1382 (capture of Isfahan in 1387, removal of the Muzaffarids from Shiraz in 1393, and expulsion of the Jalayirids from Baghdad). In 1394/95, he triumphed over the Golden Horde and enforced his sovereignty in the Caucasus, in 1398 subjugated Multan and Dipalpur in modern day Pakistan and in modern day India left Delhi in such ruin that it is said for two months "not a bird moved wing in the city."[5] In 1400/01, conquered Aleppo, Damascus and eastern Anatolia, in 1401, destroyed Baghdad and in 1402, triumphed over the Ottomans at Ankara. In addition, he transformed Samarkand into the Center of the World. An estimated 17 million people may have died from his conquests.[6]

After the end of the Timurid Empire in 1506, the Mughal Empire was later established in India by Babur in 1526, who was a descendant of Timur through his father and possibly a descendant of Genghis Khan through his mother. The dynasty he established is commonly known as the Mughal Dynasty. By the seventeenth century, the Mughal Empire ruled most of India, but later declined during the eighteenth century. The Timurid Dynasty came to an end in 1857 after the Mughal Empire was dissolved by the British Empire and Bahadur Shah II was exiled to Burma.

Due to the fact that the Persian cities were desolated by previous wars, the seat of Persian culture was now in Samarkand and Herat. These cities became the center of the Timurid renaissance[1]

Culture

Although the Timurids hailed from the Barlas tribe which was of Mongol origin, they had embraced Persian culture[7] and Persian art (distinguished by extensive adaptations from the Chinese,[1] and also Chagatay Literature,[1] converted to Islam and resided in Turkestan and Khorasan. Thus, the Timurid era had a dual character,[1] which reflected both the Turco-Mongol origins and the Persian culture as well the Persian language. The Persian language was also the state language (also known as Diwan language) of the dynasty.

Literature

Timurid literature in Persian language

Persian literature, especially Persian poetry occupied a central place in the process of assimilation of the Timurid elite to the Perso-Islamic courtly culture.[8] The Timurid sultans, especially Šāhrukh Mīrzā and his son Mohammad Taragai Oloğ Beg, patronized Persian culture. Among the most important literary works of the Timurid era is the Persian biography of Timur, known as "Zafarnāma," written by Sharaf ud-Dīn Alī Yazdī, which itself is based on an older "Zafarnāma" by Nizām al-Dīn Shāmī, the official biographer of Timur during his lifetime. The most famous poet of the Timurid era was Nūr ud-Dīn Jāmī, the last great medieval Sufi mystic of Persia and one of the greatest in Persian poetry. The most famous painter of the Timurid court, as well as the most famous of the Persian miniature painters in general, was Ustād Kamāl ud-Dīin Behzād. In addition, the Timurid sultan Ulugh Beg is known as a great astronomer, building a "observatory that was a marvel of the age."[9] Daniel says that the Timurid's were "distinguished as patrons of Islamic scholarship, literature, art] and architecture" and that several Timurid rulers were 'accomplished in these fields themselves."[10]

BaySanghur Shahnameh

Baysanghur commissioned a new edition of the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi and wrote an introduction to it. According to T. Lenz:[11]

It can be viewed as a specific reaction in the wake of Timur's death in 807/1405 to the new cultural demands facing Shahhrokh and his sons, a Turkic military elite no longer deriving their power and influence solely from a charismatic steppe leader with a carefully cultivated linkage to Mongol aristocracy. Now centered in Khorasan, the ruling house regarded the increased assimilation and patronage of Persian culture as an integral component of efforts to secure the legitimacy and authority of the dynasty within the context of the Islamic Iranian monarchical tradition, and the Baysanghur Shahnameh, as much a precious object as it is a manuscript to be read, powerfully symbolizes the Timurid conception of their own place in that tradition. A valuable documentary source for Timurid decorative arts that have all but disappeared for the period, the manuscript still awaits a comprehensive monographic study.

National literature in Chagatay language

The early Timurids played a very important role in the history of Turkic literature. Based on the established Persian literary tradition, a national Turkic literature was developed, written in the Chagatay language, the native tongue of the Timurid family. Chagatay poets such as Mīr Alī Sher Nawā'ī, Sultan Husayn Bāyqarā, and Babur encouraged other Turkic-speaking poets to write in their own vernacular in addition to Arabic and Persian.

The Bāburnāma, the autobiography of Bābur, as well as Mīr Alī Sher Nawā'ī's Chagatay poetry are among the best-known Turkic literary works and have fascinated and influenced many others world wide. The Baburnama was highly Persianized in its sentence structure, morphology or word formation and vocabulary.[12]

Art

During the reign of Timurid rule, the golden age of Persian painting was ushered. During this period as well as the Safavid dynasty, Chinese art and artists had a significant influence on Persian art. Timurid artists refined the Persian art of the book, which combines paper, calligraphy, illumination, illustration and binding in a brilliant and colorful whole.[13] It was the Mongol ethnicity of the Chaghatayid and Timurid Khans that is the source of the stylistic depiction Persian art during the Middle Ages. These same Mongols intermarried with the Persians and Turks]] of Central Asia, even adopting their religion and languages. Yet their simple control of the world at that time, particularly in the thirteenth-fifteenth centuries, reflected itself in the idealized appearance of Persians as Mongols. Though the ethnic make-up gradually blended into the Iranian and Mesopotamian local populations, the Mongol stylism continued well after, and crossed into Asia Minor and even North Africa.

Architecture

Timurid architecture

In the realm of architecture, the Timurids drew on and developed many Seljuq traditions. Turquoise and blue tiles forming intricate linear and geometric patterns decorated the facades of buildings. Sometimes the interior was decorated similarly, with painting and stucco relief further enriching the effect. Timurid architecture is the pinnacle of Islamic art in Central Asia. Spectacular and stately edifices erected by Timur and his successors in Samarkand and Herat helped to disseminate the influence of the Ilkhanid school of art in India, thus giving rise to the celebrated Mughal (or Mongol) school of architecture. Timurid architecture started with the sanctuary of Ahmed Yasawi in present-day Kazakhstan and culminated in Timur's mausoleum Gur-e Amir in Samarkand. Timur’s Gur-I Mir, the fourteenth century mausoleum of the conqueror is covered with "turquoise Persian tiles."[14] Nearby, in the center of the ancient town, there is a Persian style Madrassa (religious school)[14] and a Persian style Mosque[14] built by Ulugh Beg. The mausoleum of Timurid princes, with their turquoise and blue-tiled domes remain among the most refined and exquisite Persian architecture.[15] Axial symmetry is a characteristic of all major Timurid structures, notably the Shāh-e Zenda in Samarkand, the Musallah complex in Herat, and the mosque of Gowhar Shād in Mashhad. Double domes of various shapes abound, and the outsides are perfused with brilliantly colors. Timurs dominance of the region strengthened the influence of his capital and Persian architecture upon India.[16]

Mughal architecture

After the foundation of the Mughal Empire, the Timurids successfully expanded the Persian cultural influence from Khorasan to India, where the Persian language, literature, architecture, and art dominated the Indian subcontinent]] until the British conquest. The Mughals, Persianized Turks who invaded from Central Asia and claimed descent from both Timur and Genghis—strengthened the Persianate culture of Muslim India.[17]

The Mughal period marked a striking revival of Islamic architecture in northern India. Under the patronage of the Mughal emperors, Indian, Persian, and various provincial styles were fused to produce works of unusual quality and refinement.

The Mughal emperor Akbar the Great constructed the royal city of Fatehpur Sikri, located 26 miles west of Agra, in the late 1500s. The most famous example of Mughal architecture is the Taj Mahal, the "teardrop on eternity," completed in 1648 by the emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his wife Mumtaz Mahal who died while giving birth to their 14th child. The extensive use of precious and semiprecious stones as inlay and the vast quantity of white marble required nearly bankrupted the empire. The Taj Mahal is completely symmetric other than the sarcophagus of Shah Jahan which is placed off center in the crypt room below the main floor. This symmetry extended to the building of an entire mirror mosque in red sandstone to complement the Mecca-facing mosque place to the west of the main structure. Another structure built that showed great depth of Mughal influence was the Shalimar Gardens.

Religion

As Muslims, the Timurid rulers did much to promote Islam, building mosques and sponsoring scholarship. However, Muslims were always a minority within the Mughal Empire. Non-Muslims were at times treated harshly; both Babur and Aurangzeb destroyed Temples. Akbar, however, fused Christianity, Hinduism and Islam into a single God-centered religion, Din-i-Ilahi. At other times, their rule was marked by a high degree of religious tolerance when non-Muslims held high positions of state, no tithe was levied on non-Muslims and many people participated in religious festivals of traditions other than their own. Without denying that persecution of non-Muslims did occur under Timurid rule, Dutt says that "many Hindu and Muslim scholars studied each other's religions, while the common people existed peacefully."[18] Many Timurid rulers were advocates of the Sufu doctrine of wahdat-al-wajud, the "unity of God and the created world, which was given creative expression by a new breed of poets."[19]

Legacy

Life under Timurid rule was for much of the time politically stable, with many citizens enjoying peace and prosperity within secure borders. Perhaps the Timurids greatest achievement was their fusing of Persian and Indian forms, as Dutt comments, "the fusion of two cultures gave rise to new styles of art, architecture and music and to a new language, Urdu."[20]

The positive aspects of the Timurid legacy still contributes to interfaith harmony in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, but the negative aspect fuels inter-community (communitarian) hatred and even violence. Lessons can be learned from the legacy of Timurid rule on how to govern multi-racial, multi-religious societies.

Rulers of the Timurid Empire

- Timur (Tamerlane) 1370-1405 (771-807 AH)—with Suyurghitmiš Chaghtay as nominal overlord followed by Mahmūd Chaghtay as overlord and finally Muhammad Sultān as heir

- Pir Muhammad bin Jahāngīr 1405-1407 (807-808 AH)

Rulers of Herat

- Shāhrukh 1405-1447 (807-50 AH) (overall ruler of the Timurid Empire 1409-1447)

- Abu'l-Qasim Bābar 1447-1457 (850-61 AH)

- Shāh Mahmūd 1457 (861 AH)

- Ibrāhim 1457-1459 (861-863 AH)

- Sultān Abu Sa’id Gūrgān 1459-1469 (863-73 AH) (in Transoxiana 1451-1469)

- Yādgār Muhammad 1470 (873 AH)

- Sultān Hussayn 1470-1506 (874-911 AH)

- Badi ul-Zamān 1506-1507 (911-912 AH)

- Muzaffar Hussayn 1506-1507 (911-912 AH)

Herat is conquered by the Uzbeks under Muhammad Shaybani

Rulers of Samarkand

- Khalīl Sultān 1405-1409 (807-11 AH)

- Mohammad Taragai bin Shāhrukh-I 1409-1449 (811-53 AH) (overall ruler of the Timurid Empire 1447-1449)

- 'Abd al-Latif 1449-1450 (853-854 AH)

- ‘Abdullah 1450-1451 (854-55 AH)

- Sultān Abu Sa’id Gūrgān 1451-1469 (855-73 AH) (in Herat 1459-1469)

Abu Sa'id's sons divided his territories upon his death, into Samarkand, Badakhshan and Farghana

- Sultān ibn Abu Sa’id 1469-1494 (873-899 AH)

- Sultān Mahmūd ibn Abu Sa’id 1494-1495 (899-900 AH)

- Sultān Baysunqur 1495-1497 (900-902 AH)

- Mas’ūd 1495 (900 AH)

- Sultān Alī Mīrzā 1495-1500 (900-905 AH)

Samarkand is conquered by the Uzbeks under Muhammad Shaybani

Rulers of Mughal Empire

- Zahiruddin Babur Mirza 1526-1530 (933-937 AH)—established Mughal Dynasty in India (Mughal Empire)

- Nasiruddin Humayun Mirza 1530-1556 (937-963 AH)—ruler of Mughal Empire, son of Babur

- Kamran Mirza 1530-1557 (937-962 AH)—ruler of Kabul and Lahore, son of Babur

- Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar Mirza (Akbar the Great) 1556-1605 (963-1014 AH)—greatest ruler of Mughal Empire, son of Humayun

- Abul Qasim Muhammad bin Kamran 968 AH

- Suleiman Mirza 936-92 AH

- Shahrukh III 983-87 AH—son of Ibrahim

- Nuruddin Muhammad Jahangir 1605-1627 (1014-1036 AH)—ruler of Mughal Empire, son of Akbar and Rajput Princess Mariam Zamani

- Shahbuddin Muhammad Shah Jahan (Shah Jahan I) 1627-1658—ruler of Mughal Empire, son of Jahangir and Rajput Princess Manmati

- Mohiuddin Mohammed Aurangzeb (Aurangzeb Alamgir I) 1658-1707—ruler of Mughal Empire, son of Shah Jahan

- Bahadur Shah I (Shah Alam I) 1707-1712—son of Aurangzeb

- Jahandar Shah]], b. 1664, ruler from 1712-1713

- Furrukhsiyar, b. 1683, ruler from 1713-1719

- Rafi Ul-Darjat, ruler 1719

- Rafi Ud-Daulat (Shah Jahan II), ruler 1719

- Nikusiyar, ruler 1719

- Muhammad Ibrahim, ruler 1720

- Muhammad Shah, b. 1702, ruler from 1719–1720, 1720-1748

- Ahmad Shah Bahadur, b. 1725, ruler from 1748-1754

- Alamgir II, b. 1699, ruler from 1754-1759==son of Jahandar Shah

- Shah Jahan III, ruler 1759

- Shah Alam II, b. 1728, ruler from 1759-1806

- Akbar Shah II, b. 1760, ruler from 1806-1837

- Bahadur Shah II (Bahadur Shah Zafar) 1837-1857—last ruler of the Timurid Dynasty

Heads of the Timurid Dynasty

- Bahadur Shah II (1857–1862)

- Shahzada Muhammad Hidayat Afshar, Ilahi Bakhsh Bahadur]] (1862–1878)

- Shahzada Muhammad Sulaiman Shah Bahadur (1878–1890)

- Shahzada Muhammad Kaiwan Shah Gorkwani, Suraya Jah Bahadur (1890–1913)

Mirza Salim Muhammad Shah Bahadur]] (1913–1925)

- No recognized head of the family (1925–1931)

Shahzada Muhammad Khair ud-din Mirza, Khurshid Jah Bahadur (1931–1975)

- Mirza Ghulam Moinuddin Muhammad, Javaid Jah Bahadur (1975-Present)

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 The Columbia Encyclopedia, Timurids. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ↑ Roxburgh (2005), 130.

- ↑ Chaliand and Berrett (2004), 75.

- ↑ Manz (1989), 109.

- ↑ Marozzi (2006), 274.

- ↑ Matthew White, Selected Death Tolls: Timur Lenk (1369–1405), Historical Atlas of the 20th Century. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ↑ F. Lehmann, Zaher ud-Din Babor - Founder of Mughal empire, Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ↑ Roxburgh (2005), 130.

- ↑ Lewis Macleod, Uzbekistan restores Timurid legacy, BBC. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ↑ Daniel (2001), 81-82.

- ↑ T. Lenz, Baysonghori Shahnameh, Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ↑ Dale (2004), 150.

- ↑ Onians (2004), 132.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Norwich (1975), 278.

- ↑ Kennedy (2007), 237.

- ↑ Fletcher and Cruickshan (1996), 606.

- ↑ Canfield (1991), 20.

- ↑ Dutt (2006), 76.

- ↑ Chandra (1999), 14.

- ↑ Dutt (2006), 76.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Canfield, Robert Leroy. 1991. Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective. School of American Research advanced seminar series. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521390941.

- Chaliand, Gérard, and A.M. Berrett. 2004. Nomadic Empires: From Mongolia to the Danube. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9780765802040.

- Chandra, Satish. 1999. Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals. New Delhi, IN: Har-Anand Publications. ISBN 9788124105221.

- Dale, Stephen Frederic. 2004. The Garden of the Eight Paradises: Bābur and the Culture of Empire in Central Asia, Afghanistan and India (1483-1530). Brill's Inner Asian library, v. 10. Leiden, NL: Brill. ISBN 9789004137073.

- Daniel, Elton L. 2001. The History of Iran. The Greenwood histories of the modern nations. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313307317.

- Dutt, Sagarika. 2006. India in a Globalized World. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719069000.

- Fletcher, Banister, and Dan Cruickshank. 1996. Sir Banister Fletcher's A History of Architecture. London, UK: Architectural Press. ISBN 9780750622677.

- Kennedy, Hugh. 2007. The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World we Live in. Philadelphia, PA: Da Capo. ISBN 9780306815850.

- Manz, Beatrice Forbes. 1989. The Rise and Rule of Tamerlane. Cambridge studies in Islamic civilization. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521345958.

- Marozzi, Justin. 2006. Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, Conqueror of the World. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 9780306814655.

- Norwich, John Julius. 1975. Great Architecture of the World. New York, NY: Random House. ISBN 9780394498874.

- Onians, John, and Oxford University Press. 2004. Atlas of World Art. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195215830.

- Roxburgh, David J. 2005. The Persian Album, 1400-1600: From Dispersal to Collection. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300103250.

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.