Sweat lodge

The sweat lodge (also called purification ceremony, sweat house, medicine lodge, medicine house, or simply sweat) is a ceremonial sauna and is an important event in some North American First Nations or Native American cultures. There are several styles of sweat lodges that include a domed or oblong hut similar to a wickiup, or even a simple hole dug into the ground and covered with planks or tree trunks. Stones are typically heated in an exterior fire[1] and then placed in a central pit in the ground.

World examples

One of the early non-Indian occurrences can be found in the fifth century B.C.E., when Scythians constructed pole and woolen cloth sweat baths.[2]

Vapour baths were in use among the Celtic tribes, and the sweat-house was in general use in Ireland down to the 18th, and even survived into the 19th century. It was of beehive shape and was covered with clay. It was especially resorted to as a cure for rheumatism.[3]

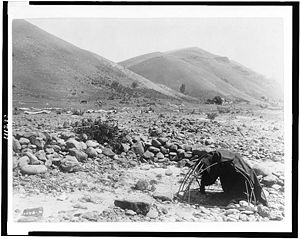

Native Americans in many regions employed the sweat lodge. For example, Chumash peoples of the central coast of California built sweat lodges in coastal areas[4] in association with habitation sites.

Traditions

Rituals and traditions vary from region to region and from tribe to tribe. They often include prayers, drumming, and offerings to the spirit world. In some cultures a sweat-lodge ceremony may be a part of another, longer ceremony such as a Sun Dance. Some common practices and key elements associated with sweat lodges include:

- Orientation – The door usually faces the fire. The cardinal directions usually have distinct symbolism in Native American cultures. The lodge may be oriented within its environment for a specific purpose. Placement and orientation of the lodge within its environment often facilitates the ceremony's connection with the spirit world.

- Construction – The lodge is generally built with great care and with respect to the environment and to the materials being used. Many traditions construct the lodge in complete silence, some have a drum playing while they build, other traditions have the builders fast during construction.

- Clothing – In Native American lodges participants usually wear a simple garment such as shorts or loose dresses.

- Offerings – Various types of plant medicines are often used to make prayers, give thanks or make other offerings. Prayer ties are sometimes made.

- Support – In many traditions, one or more persons will remain outside the sweat lodge to protect the ceremony, and assist the participants. Sometimes they will tend the fire and place the hot stones, though usually this is done by a designated firekeeper. In another instance, a person that sits in the lodge, next to the door, is charged with protecting the ceremony, and maintaining lodge etiquette.

- Darkness - Many traditions consider it important that sweats be done in complete darkness.

Etiquette

The most important part of sweat lodge etiquette is respecting the traditions of the lodge leader. Some lodges take place in complete silence, while others involve singing, chanting, drumming, or other sound. It is important to know what is allowed and expected before entering a lodge. Traditional tribes hold a high value of respect to the lodge. In some cultures, objects, including clothing, without a ceremonial significance are discouraged from being brought into the lodge. Most traditional tribes place a high value on modesty as a respect to the lodge. In clothed lodges, women are usually expected to wear skirts or short-sleeved dresses of a longer length. In some traditions, nudity is forbidden, as are mixed sex sweats, whereas in others nudity is considered to have a greater connection with the spiritual aspect of your sweat. Some lodge leaders do not allow menstruating women. Perhaps the most important piece of etiquette is gratitude. It is important to be thankful to the purpose of the sweat, the people joining you in the lodge, and those helping to support the sweat lodge.

Risks

Wearing metal jewelry can be dangerous: metal objects may become hot enough to burn the wearer. Contact lenses and synthetic clothing should not be worn in sweat lodges as the heat can cause the materials to melt and adhere to eyes, skin, or whatever they might be touching. Because of the danger of melting, cotton clothing is better for lodges than synthetic.[5]

There have been reports of lodge-related deaths resulting from overexposure to heat, dehydration, smoke inhalation, or improper lodge construction leading to suffocation.[6][7] In October 2009, during a New Age retreat organized by James Arthur Ray, three people died and 21 more were sickened from an overcrowded and improperly set up sweat lodge containing some 60 people and located near Sedona, Arizona.[8] Ray was arrested by the Yavapai County Sheriff's Office in connection with the deaths on February 3, 2010, and bond was set at $5 million.[9] In response to these deaths, Lakota spiritual leader Arvol Looking Horse issued a statement reading in part:

Our First Nations People have to earn the right to pour the mini wic'oni (water of life) upon the inyan oyate (the stone people) in creating Inikag'a - by going on the vision quest for four years and four years Sundance. Then you are put through a ceremony to be painted - to recognize that you have now earned that right to take care of someone's life through purification. They should also be able to understand our sacred language, to be able to understand the messages from the Grandfathers, because they are ancient, they are our spirit ancestors. They walk and teach the values of our culture; in being humble, wise, caring and compassionate. What has happened in the news with the make shift sauna called the sweat lodge is not our ceremonial way of life![10]

Even people who are experienced with sweats, and attending a ceremony led by a properly-trained and authorized Native American ceremonial leader, could suddenly experience problems due to underlying health issues. It is recommended that a physician check people intending to have a sweat-lodge experience, and that people only attend lodges with reputable people.

If rocks are used, it is important not to use river rocks, or other kinds of rocks with air pockets inside them. Rocks must be completely dry before heating. Rocks with air pockets or excessive moisture will likely crack and possibly explode in the fire or when hit by water. This can result in razor-sharp fragments and splinters striking participants with sufficient force to effect injury. Even rocks used before may absorb humidity or moisture leading to cracks or shattering.

There is also a risk posed by modern chemical pesticides, or inappropriate woods, herbs, or building materials being used in the lodge.

Lawsuit filed by the Lakota Nation

On November 2, 2009, the Lakota Nation filed a lawsuit against the United States, Arizona State, James Arthur Ray and Angel Valley Retreat Center site owners, to have Ray and the site owners arrested and punished under the Sioux Treaty of 1868 between the United States and the Lakota Nation, which states that “if bad men among the whites or other people subject to the authority of the United States shall commit any wrong upon the person or the property of the Indians, the United States will (...) proceed at once to cause the offender to be arrested and punished according to the laws of the United States, and also reimburse the injured person for the loss sustained.”[citation needed]

The Lakota Nation holds that James Arthur Ray and the Angel Valley Retreat Center have “violated the peace between the United States and the Lakota Nation” and have caused the “desecration of our Sacred Oinikiga (purification ceremony) by causing the death of Liz Neuman, Kirby Brown and James Shore”. As well, the Lakota claim that James Arthur Ray and the Angel Valley Retreat Center fraudulently impersonated Indians and must be held responsible for causing the deaths and injuries, and for evidence destruction through dismantling of the sweat lodge. The lawsuit seeks to have the treaty enforced and does not seek monetary compensation.[11]

Preceding the lawsuit, Native American experts on sweat lodges criticized the reported construction and conduct of the lodge as not meeting traditional ways ("bastardized", "mocked" and "desecrated"). Indian leaders expressed concerns and prayers for the dead and injured. The leaders said the ceremony is their way of life[citation needed] and not a religion, as white men see it. It is Native American property protected by U.S. law and United Nation declaration. The ceremony should only be in sanctioned lodge carriers' hands from legitimate nations. Traditionally, a typical leader has 4 to 8 years of apprenticeship before being allowed to care for people in a lodge, and have been officially named as ceremonial leaders before the community. Participants are instructed to call out whenever they feel uncomfortable, and the ceremony is usually stopped to help them. The lodge was said to be unusually built from non-breathable materials. Charging for the ceremony was said to be inappropriate. The number of participants was criticized as too high and the ceremony length was said to be too long. Respect to elders' oversight was said to be important for avoiding unfortunate events. The tragedy was characterized as "plain carelessness", with a disregard for the participants' safety and outright negligence.[12] The Native American community actively seeks to prevent abuses of their traditions. Organizers have been discussing ways to formalize guidance and oversight to authentic or independent lodge leaders.[11][13][14][15][16][17]

Inipi (Lakota Sweatlodge)

The I-ni-pi ceremony, a type of sweat lodge, is a Lakota purification ceremony, and one of the Seven Sacred Rites of the Lakota people.[18] It is an ancient and sacred ceremony of the Lakota people and has been passed down through the generations of Lakota.

The full ceremony is not taught to non-Lakotas, but in rough detail it involves an I-ni-pi lodge - a frame of saplings covered with hides or blankets. Stones are heated in a fire, then placed into a central pit in the lodge. Water is then poured on the stones to create hot steam. Traditional prayers and songs are offered in the Lakota language.

Those who have inherited and maintained these traditions have issued statements about the standards to be observed in the I-ni-pi.[18][19] In the March 2003 meeting it was agreed among the spiritual leaders and Bundle Keepers of the Lakota, Dakota, Nakota, Cheyenne and Arapahoe Nations that:

I-ni-pi (Purification Ceremony): Those that run this sacred rite should be able to communicate with Tun-ca-s'i-la (our Sacred Grandfathers) in their Native Plains tongue. They should also have earned this rite by completing Han-ble-c'i-ya and the four days and four years of the Wi-wanyang wa-c'i-pi.[18]

This also follows upon the decisions made at the Lakota Summit V, an international gathering of US and Canadian Lakota, Dakota and Nakota Nations, where about 500 representatives from 40 different tribes and bands of the Lakota unanimously passed a "Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality." The declaration was unanimously passed on June 10, 1993. Among other things, it specifies that these ceremonies are only for those of the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota Nations.[19]

One concern about outsiders trying to perform these ceremonies is that, not only does it go against the express wishes of the traditional healers who have inherited these ceremonies, but that those who do not know how to do them properly have in some cases caused dehydration and heat stroke, resulting in injury and even deaths.[6][7]

Temazcal

A temazcal (also written as temezcal, temascal, or temescal) is a type of sweat lodge which originated with pre-Hispanic Indigenous peoples in Mesoamerica. The word temazcal comes from the Nahuatl (Aztec) word temazcalli which comes from two words, temas which means bath (or teme to bathe), and calli meaning house.[20][21] The Mayans called these sweat baths Zumpul-che, meaning "a bath for women after childbirth and for sick persons used to cast out disease in their bodies."[21]

The temazcal sweatlodge in Mesoamerica is usually a permanent structure, unlike in other regions. Constructed from volcanic rock and cement it is usually a circular dome, although rectangular ones have been found at certain archeological sites. To produce the heat, volcanic stones, which do not explode from the high temperature, are heated and then placed in a pit located in the center or near a wall of the temazcal.

In ancient Mesoamerica the temazcal was used as part of a curative ceremony thought to purify the body after exertion such as after a battle or a ceremonial ball game. It was also used for healing the sick, improving health, and for women to give birth. It continues to be used today for spiritual and health reasons in Indigenous cultures of Mexico and Central America that were part of the ancient Mesoamerican region.

The temazcal involved the worship of a goddess, Temazcalteci, "the grandmother of the baths," and incorporated all the elements of Aztec mythology. The Spanish colonialists, horrified at the idea of people of both genders bathing naked together and participating in what they assumed to be immoral acts, determined to eradicate this practice that was so closely connected to pagan beliefs. Despite their best efforts, however, the temazcal survived, practiced secretly in remote locations.[20] It is currently being recovered by all sectors of society in that part of the world and is used as a cleansing of mind, body, and spirit.

Notes

- ↑ Ella E. Clark, Indian Legends of the Pacific Northwest, illustrated by Robert Bruce Inverarity, 2003, University of California Press, 225 pages ISBN 0520239261

- ↑ Joseph Bruchac, The Native American Sweat Lodge: History and Legends, 1993, The Crossing Press, 145 pages ISBN 089594636X

- ↑ "SWEAT, SWEAT-HOUSE". Encyclopædia of religion and ethics 12. (1922). T. & T. Clark. Retrieved on 23 Nov 2010 (text verbatim).

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan, Los Osos Back Bay, Megalithic Portal, editor A. Burnham

- ↑ Sang-Hun, Choe, "Kiln Saunas Make a Comeback in South Korea", The New York Times, August 26, 2010.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Herel, Suzanne, "2 seeking spiritual enlightenment die in new-age sweat lodge", San Francisco Chronicle, Hearst Communications, 2002-06-27. Retrieved 2006-09-26.

- ↑ John Dougherty, New York Times, "Deaths at Sweat Lodge Bring Soul-Searching

- ↑ Felicia Fonseca, Associated Press "Motivational speaker charged in sweat lodge deaths"

- ↑ Concerning the deaths in Sedona By Arvol Looking Horse. Published: Oct 16, 2009

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Nina Rehfeld, "Lakota Nation files lawsuit against parties in sweat lodge incident", www.sedona.biz, 11/12/2009 [1]

- ↑ Bob Goulais,"Dying to experience native ceremonies",North Bay Nugget, 10/24/2009 [2]

- ↑ Chief Chemito, Comments reported on Phoenix Fox 10 by Miriam Garcia, 10/10/2009 [3]

- ↑ Valerie Taliman, "Taliman: Selling the sacred", Indian Country Today, 10/13/2009 [4]

- ↑ Lindsay Hocker, "Sweat lodge incident 'not our Indian way", Quad-Cities Online, 10/14/2009 [5]

- ↑ Chief Arvol Looking Horse, "Concerning the deaths in Sedona", Indian Country Today, 10/16/2009 [6]

- ↑ All Nations Indigenous Native American Indian Cultural Center, "Native Elder Addresses Deaths In Sweat Lodge", BlackHillsToday, 10/17/2009 [7]

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "Looking Horse Proclamation on the Protection of Ceremonies", March 13, 2003. Retrieved April 21, 2008

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality" June 10, 1993. Retrieved April 21, 2008

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Horacio Rojas Alba, "Temazcal: The Traditional Mexican Sweat Bath" Tlahui-Medic 2 (1996). Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Mikkel Aaland, "Origin of the Temescal" Native American Sweat Lodge. 1997. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bruchac, Joseph. The Native American Sweat Lodge: History and Legends. The Crossing Press, 1993. ISBN 089594636X

- Bucko, Raymond A. The Lakota Ritual Of The Sweat Lodge. University of Nebraska Press, 1998. ISBN 0803212720

- Clark, Ella E. Indian Legends of the Pacific Northwest. University of California Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0520239265

- McGarvie, Irene. The Sweat Lodge is For Everyone: We are all Related. Nixon-Carre Ltd., 2009. ISBN 978-0973747065

External links

- A Sweat Lodge

- Article on the use of the temazcal among the Tzeltal-Tzotzil Maya of Chiapas, Mexico

- The Native American Sweatlodge A Spiritual Tradition

- Sweat Lodges

- Sweat Lodge

- Sweat Lodge Etiquette

- Construction and Symbolism of the Sweat Lodge

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.