Difference between revisions of "Shiva" - New World Encyclopedia

m (Robot: Remove claimed tag) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | ||

[[Image:statueofshiva.JPG|right|thumb|A statue of Shiva near [[Indira Gandhi International Airport]], [[Delhi]]]] | [[Image:statueofshiva.JPG|right|thumb|A statue of Shiva near [[Indira Gandhi International Airport]], [[Delhi]]]] | ||

Revision as of 16:20, 2 April 2008

Shiva (Devanagari शिव) is one of the foremost Hindu gods, enumerated among the Hindu Trinity as the god of destruction. His theonym derives from the Vedic Sanskrit adjective for "auspicious" or "propitious", marking his development out of and in many ways in contrast to Rudra, his fearsome precursor from the Rg Veda. Shiva's most popular epithets include Mahesvara (or "great god"), Shankara, Shambu, Pashupati, Chandramoli and even Rudra, among many others.

The embodiment of capriciousness, Shiva is the god in whom opposites come to be dissolved; as such, he is characterized by polarities such as asceticism and eroticism, benevolence and wrath, beauty and horror. Accordingly, he has become a repository of diverse imagery and symbolism, though he is ubiquitously recognized by the linga, a phallic column which has historically been one of the most widely venerated objects in the cult of Shiva. Shaivism, the second largest monotheistic school in contemporary Hinduism, is dedicated to the worship of Shiva as the supreme divinity.

Origins

Pre-Vedic

Relics obtained by archaeologists from the ruins of the Indus Valley Civilization suggest that the worship of a god resembling Rudra-Shiva was practiced between 2800 - 1500 B.C.E. These artifacts include numerous phallic objects carved on rock surfaces which closely resemble lingas (see below), as well as the "Pashupati seal" found at Mohenjo-daro. An engraving upon this seal depicts a horned male figure with an erect phallus who is surrounded by an assortment of wild creatures. Considering the phallic imagery, which has traditionally been considered the emblematic of Shiva, as well as the inclusion of animals, this image appears to depict a prototype of the Vedic deity Pashupati, the "lord of the creatures". Pashupati would eventually come to be considered an aspect of Shiva.[1] The central figure is also seated in a yogic posture, perhaps foreshadowing the associations Shiva would later come to assume with meditatation and asceticism.

Rudra

With the dissolution of the Harrapan culture, religion in the Indus Valley region and the Indian subcontinet as a whole underwent significant changes. The Rg Veda (c. 1200 B.C.E.) fostered the transformation of the initial proto-Shiva figure into Rudra, a terrifying and mercurial diety of the wild who held jurisdiction over sickness and storms. Although only four of the Rg Vedic hymns are dedicated exclusively to this character, he plays an important mythological role in the Vedas in his associations with the fire god Agni and the sacrificial beverage Soma. Not unlike Shiva, Rudra is connected with wildlife in his function as "lord of the cattle" (pasunam patih) and "wearer of the animal hide". Moreover, Rudra's nature is highly contrary: not only is the divine custodian of disease, but he also possesses the ability to conjure medicine to cure any given ailment. As such, great efforts are made to appease the deity in the few hymns that are dedicated to him in hopes that his beneficence will supplant his malevolence. As a proper name, Shiva means "The Auspicious One", a moniker which is first applied to Rudra in the Yajurveda. This may have originally been used as a euphemistic epithet for Rudra to distinguish his horrific appearance from his more magnanimous form. With this connection in mind, Shiva and Rudra are typically viewed as the same divine personality in contemporary Hinduism, and are often referred to mutually as Rudra-Shiva by scholars in recognition of the inextricable mythological and ritual link between the two deities.

Supremacy

In the later Vedas, Rudra came to inherit new monikers such as Bhava, Sarva, Mahadeva, and the aforementioned Shiva, all of which seem to have been names of regional or indigenous gods of non-Aryan of non-Vedic origin. In the divine persona of Rudra the traits of these deities seems to have been syncretized into one divine personality. By the time of the Upanishads (7th century CE or later), Rudra had by all indications assumed the characteristic traits of a single, Supreme Lord, including omnipotence, omnipresence, and complete transcendence. In the Svetsvara Upanishad, for instance, Rudra-Shiva is proclaimed to be identical with Purusha, the primordial man, and even Brahman, the ontological ground of all being. By this point he was also perceived to be protector and creator of all things, and bore more and more striking resemblance to Shiva as he is known today.

Shiva would go on to develop his own distinct character, eventually supplanting Rudra entirely. While Rudra proper quickly fell out of currency in the ritual sphere, his influence upon Shiva was lasting: not only did Rudra provide much of the macabre imagery still associated with Shiva, but he also established Shiva's status as a divine "outsider", representing the religious life as it existed away from societal norms. Although many opposites met in Rudra, it was not until the character of Shiva was fully developed that these opposites were so splendidly reconciled.

Iconography

Depiction

Shiva is identified in depictions by some of the most intricate and idiosyncratic imagery in the Hindu tradition. Inscribed on his divine person as a constellation of multifarious symbols is the sheer diversity of the mythologies subsumed within his character. Shiva is commonly depicted as a relatively anthropomorphic light-skinned man with either two or four arms. He may also take the form of a young boy or a weathered old man. His skin is covered in funerary ashes, marking his proclivity to dwell in cremation grounds, and suggesting the potency of his ascetic heat. Some depictions attribute Shiva with six faces. His clothing is limited to an animal skin drawn round his waist, usually that of an elephant, deer, or tiger, most commonly the latter. This is based upon a story wherein Shiva evokes the anger of some forest ascetics who promptly let loose a vicious tiger to destroy him. Shiva seizes the beast without effort and strips its skin with the nail of his little finger, symbolizing his control over imperious aspects of character such as lust and pride.

Shiva's hair is long and matted in the style typical of ascetics, marking his status as the paramount yogi, unmatched in his renunciation of the world. From his hairline hangs the crescent moon, which has earned him the epithet Chandramoli or "moon-headed". It is also in his hair where Ganga, the goddess of the Ganges, is said to reside, and the great waters are often shown pouring out in a stream from Shiva's locks. On his forehead just above the bridge of the nose there sits a third-eye, which represents the heat-producing seat of Shiva's ascetic power.

Shiva's throat is blue as a reminder of his service to humankind. In a famous myth describing how the gods churned the cosmic milk-ocean for the purpose of gaining the nectar of immortality, it is said that preceding the precious fluid there arose from the ocean fourteen precious articles, among which was the lethal Halahala poison. In order to save humanity and the gods from its veritable potency, Shiva drank the poison, which left his throat with a bluish hue thereafter. Around Shiva's collar along with japa beads is wrapped a live serpent, usually a cobra, which represents immortality.

As far as accessories go, Shiva most famously carries the trident, the three prongs representing the creative, preservative, and destructive functions of the divine triad. The very fact that the trident is held in the hand of Shiva affirms that all three aspects are ultimately under his control. Shiva sometimes carries the skull of Brahma, whom he beheaded, and therefore makes note of the fact that all things in the universe perish while Shiva himself remains undying. One of his hands is typically held out in the Abhya Mudra, a sign of fearlessness and an offering of shelter for the helpless. He is often accompanied in images by Nandin, a white bull which is considered his divine vehicle or vahana. Mount Kailash, upon the peak of which Shiva is said to reside in constant meditation, often forms the backdrops for pictures of the god.

Linga

The single most popular symbol of Shiva is the linga (or lingam), a phallic shape which embodies both his regenerative capability as not only the destroyer but also the reproducer of the universe. Additionally, the never-wilting phallus represents Shiva's persistent restraint from sex and the complete absence of sexual temptation, which has allowed him to accumulate a powerful reservoir of ascetic heat. As such, the consistently erect phallus of Shiva speaks to his infinite creative potentiality. In temples, lingam are commonly found in proximity to the yoni, the symbol of the female principle from which the male principle is considered inextricably linked. In fact, Yonis often form the base of the linga statues.

The linga has traditionally been the focal point of Shaivite devotion throughout India in both temples and family shrines, and has become the definitive mark of Shaivism. Lingas used in worship are commonly of two varieties: those sculpted out of wood or stone by humans and those that occur naturally, such as the ice Lingam located at the Cave Temple of Lord Amarnath in Kashmir. The twelve Jyotirlinga shrines, where Shiva is worshipped in the form of a Jyotirlingam (or "Lingam of light") are among the most esteemed worship sites in the Shaivite tradition.

Forms

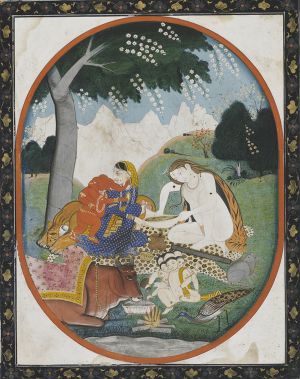

Ardhanarisvara

As is suggested by the inseparability of the lingam and yoni, the male and female principles are closely interwoven in the theology of Shiva. Shiva, the supreme masculine power in the universe, works in concert with Shakti, the equivalent female energy. While Shiva represents an unchanging, infinite, and transcendent reality that provides the monistic essence of the universe, Shakti is considered the active force behind all action and existence in the phenomenal cosmos. Without this dynamic and decidedly feminine power which actualizes the potentiality of the masculine, Shiva's creative power would be rendered impotent. In religious art, this mutual dependence of Shakti and Shiva in creation is poignantly expressed by way of the half-male, half-female figure known as Ardhanarisvara or "The lord who is half woman". For such depictions, the female Shakti half is represented by Shiva's wife Parvati, and the male half is represented by her husband Shiva. This suggests the necessary pairing of male and female in order to create life, and their equal contribution to such a process.

However, some feminists have disagreed with the assertion that Ardhanisvara represents equality of the sexes. Such critics point out that the literal meaning of Ardhanarisvara refers to the "lord who is half woman" as opposed to a more mutual "half-man, half-woman." This phrasing suggests the inherent male nature of the deity and privileges him with the status of isvara—"god," "lord," or "master;" Parvati meanwhile, is simply "woman" (nari). It has also been noted that the right side of the body upon which Shiva is placed is traditionally considered superior to the left in the Indian tradition.[2] Thus, the placement of Shiva on the right side of Ardhanarisvara affords him implicit privilege over his wife on the left.

Nataraja

Shiva Nataraja refers to Shiva in his form as the cosmic dancer, based upon two dances which are attributed to Shiva in the Puranas: the Tandava, the dance of destruction, and the Siva-lila, the dance of love. The Tandava involves a frenzied constellation of movements which set in motion the annihilation of the universe. During this dance, Shiva careers down Mount Kailash while a company of half-human, half-animal creatures cheers urge him on. In some instances, this dance involves Shakti as, who performs the dance atop Shiva's corpse. The Shiva Nataraja's beautiful dance is also connected to Shakti, particularly his marriage to Parvati, having first been performed in order to attract the amorous attention of his future wife. All throughout the dance, Shiva is clad in an alluring red garment with a carpet on his back, holding in his left hand a horn and in his right a drum, much to the delight of Parvati.

The South Indian Koyil Purana reverberates this notion of Shiva as a dancer. This text narrates a story which has Shiva going to a forest in which many Mimamsakas are living, where he initiates an argument with them. After sending a number of threatening beings at him in vain (including the aforementioned tiger), the unphased Shiva begins to dance, and so the annoyed sages conjure up a dwarf by the name of Muyalaka to neutralize him. When Muyalaka makes his attempt to kill Shiva, the dancing god uses his foot to break the dwarf's neck, and continues on with his dance. This image of Shiva Nataraja dancing atop the dwarf has been immortalized in South India art, ostensibly commemorating Shiva's unmatched ability to conquer evil, which is personified by the dwarf. This image is often encircled by flames, which represents the consumption of the illusory physical universe by the untainted reality of Shiva.

Bhairava

Bhairava refers to Shiva in his most terrible form. Legend has it that when Shiva asked Lord Brahma whom exactly was the supreme entity in the universe, Brahma named Vishnu. Livid with the creator god, Shiva took on his Bhairava form and sliced off one of Brahma's five heads. This act left Bhairava-Shiva guilty of the atrocious crime of Brahmin murder, and from that point on, he was forced to perform immense penance to redeem himself for this most heinous of transgressions. For many years to come, Bhairava carried with him the skull of the Brahman wherever he wandered. Because of his hideous and terrifying persona, Bhairava is said to have been honoured by a number of highly unorthodox practices such as offerings of liquor and meat all in an effort to appease his blood-thirstiness. He was considered to be most adequately propitiated, though, by human or animal sacrifice, an act not unheard of in ancient India.[3] The Kapalikas (see below), a medieval Shavite sect, dedicated their personal devotion to Shiva in this form. Bhairava is also particularly popular in Nepal.

Avatars

While bearing only minute resemblance to the avatara doctrine which is so theologically crucial in the Vaishnava tradition, Shiva has been attributed with a number of incarnations of his own. These include the Panchabrahma avatars (Sadyojata, Vamadeva, Tatpurusa, Aghora, and Isana), the Sivastamurti avatars (Sarva, Bhava, Rudra, Ugra, Bhima, Isa, Mahadeva, and Pasupati), most of whome are simply alternative names for the deity which appear in the various Vedas. Also listed as avatars are Nandin, the white bull with whom Shiva is commonly pictured, as well as Sardula, Salabhava, Grhapatya, Yaksesavara, Kirata. These avatars are accompanied in the Shiva-Purana by a female consort, each of whom is herself considered an incarnation of Parvati. In terms of historical individuals, Shankara, the influential ninth century founder of the non-dualist Advaita philosophy, is also considered Shiva incarnate. These avatars are by no means universally accepted throughout Shaivism as a whole; further, salvific power, when used in the mythology of these avatars, is always accredited solely to Shiva as opposed to his given incarnation.

Shiva & Other Dieties

Sati

One of the most important associations made in the mythology of Shiva between he and another deity is that with Sati, his first wife. Sati is the daughter of Daksa, and from an early age the purpose of her existence singularly centers upon making Shiva her husband. She was given this impetus by Brahma, who had earlier on been derisively mocked by Shiva when he had experienced pangs of incestuous lust for his own daughter. In order to exact some retribution, Brahma saw to it that Shiva would himself fall prey to sexual passion, in this case for Sati.

Unfortunately for Sati, her life's ambition is made difficult since it is virtually impossible to draw Shiva out of his ascetic practices and into a domestic life. It is only through her own appeals to asceticism and devotion that she is able to stir Shiva's desire. At this point she asks Shiva to marry her, and he agrees. The marriage is traditional despite Shiva's impatience with the ritual and formalities. Over the course of the proceedings, Daksa begins to express trepidations with his soon-to-be-son-in-law's unsightly appearance and licentious comportment, and conflict develops between the two. After the wedding, Siva and Sati decamp to Mount Kailash where they bask in one another's company. Meanwhile, a spiteful Daksa organizes a great sacrifice to which all divine beings are invited, with the exception of the newlyweds. Furious with her father's unshakeable disapproval of her new husband, Sati kills herself.

When he hears of Sati's death, Shiva is furious and creates a variety of fierce beings including the demon Virabhadra. These demons overtake the various divinities assembled at Daksa's grand sacrifice, and end up killing Daksa. Shiva then enters the sacrifice and it proceeds without further issue. In alternative versions of the story, Shiva carries Sati's lifeless body all over the universe, causing various cosmic disturbances along the way. All the while, Vishnu follows Shiva throughout his destructive journey, slicing off parts of Sati's corpse as he goes. These parts fall to earth, marking sacred places commemorating the feminine divine (or Shakti peethas) wherever they land. Once all the parts of Sati's body have been dispersed, Shiva returns to solitude in his mountain abode. Not only does this myth illustrate the destructive power of Shiva, but it also puts forward the idea that it is the feminine power (represented here by Sati) that makes the hidden power of Shiva accessible to human beings in the physical world.

Parvati

After Sati's death, Shiva remarries, this time with the maiden Parvati. Prior to Parvati's birth, a demon by the name of Taraka had been granted a boon which made him invincible to any creature except for a child of Shiva. Because of Shiva's reputed asceticism and total abstinence from sex, the gods had to partake an active search to find a woman capable of pulling Shiva out of his austerities and into a sexual encounter. Sati was said to have consented to be reborn for the purpose of helping the gods, and so she readily took birth as Parvati. Much like Sati, Parvati became obsessed with Shiva at a young age. The possibility of a marriage between she and Shiva seemed even more promising by the fact that a rishi predicted, to the delight of her parents, that Parvati would marry a naked yogi.

Parvati made some initial attempts to attract Shiva's attention, but once again the god was too deeply immersed in his ascetic practices to notice her, considering women an unnecessary distraction to his meditations. Desperate to defeat Taraka, the gods sent Kama, the god of love, to stimulate Shiva's lust. The Cupid-like Kama fired his arrows-of-desire at Shiva in hopes of sending him into a lustful swoon, but Shiva quickly became aware of the love-god's trickery. Irritated by the momentary distraction, Shiva unveiled his dreadful third eye and blasted Kama with his ascetic fire, reducing him to a pile of ash. As a consequence of Shiva's actions, the entire earth was left barren and infertile in Kama's absence.

Although the gods mourned Kama's incineration, his work was not entirely in vain, as Shiva would indeed fall in love with Parvati, nonetheless. This occurred after Parvati surpassed all of the great sages in her austerities, and accumulated so much ascetic heat that she threatened even the gods themselves. This impelled them to approach Shiva and persuade him to marry her. Despite attempts made by agents of Shiva to test her devotion, Parvati proved faithful only to Shiva, and so he agreed to marry her. After the wedding, Shiva brings Kama back to life from the ashes at the request of Parvati and the desperate pleas of Ratri, Kama's own spouse. Shiva resurrected Kama not as an anthropomorphic being but as an incorporeal image only, as a representation of the fact that the true state of love is emotional and mental rather than simply physical. With that, the sexual and procreative aspect of the world was restored, and Shiva and Parvati were able to proceed in the consummation of their newly minted marriage.

Just as in Shiva's previous marriage, he and his new bride depart to Mount Kailash for purposes of their honey-moon. Witnessing Shiva and Parvati's prodigious feats of love-making, the gods grew fearful of the potentially insurmountable strength that a child created by such powerful beings might possess. They promptly interrupt Shiva and Parvati in the midst of their embrace, and, as a result, Shiva's semen, fiery with his intense ascetic heat, lands in the Ganges River. It was at this point that the child Kartikeya was conceived and grew into an infant, whom Parvati raised as her own. Kartikeya went on to defeat the demon Taraka, thereby saving the world and so, once again, the efforts made by a woman to domesticate Shiva serve the benefit of the entire world.

Ganesha

Shiva is also considered father, albeit indirectly, of the popular elephant-headed god Ganesha. The most common account of Ganesha's birth begins with Shiva leaving Parvati for an extended period of time to engage in further meditation upon Mount Kailash. His absence inspires intense loneliness within the goddess and, longing for some company, she conjures the shape of the young Ganesha from flecks of her discarded skin. She quickly orders her new son to stand guard at the door of her private chamber while she bathes. Eventually, Shiva returns from his meditation and attempts to access Parvati's private chamber. Ganesha refuses to let him in and a struggle ensues, which ends with Shiva beheading his adversary. Hearing the commotion, Parvati comes out of her bath and informs Shiva that he has killed her child, and in her anger threatens to destroy the entire universe if the situation is not rectified. Shiva promptly sends off his servants with orders that they should obtain the head of the first being they come across as a replacement for the missing head of the boy. The servants find an elephant and cut off its head, which they place upon Ganesh's shoulders once they have returned. When Ganesh regains consciousness, Shiva adopts him as his own. [4]

Another story claims that Shiva created Ganesha by way of his laughter alone. After Ganesha's birth, Shiva became concerned that the youth was excessively beautiful, and so he cursed Ganesha to have the head of an elephant and a protruding belly in order to make his appearance more comical and less aesthetically pleasing.[5]

Vishnu

Shiva and Vishnu, representing the two most popular male gods in the Hindu pantheon and each having inspired his own monotheistic tradition in the forms of Shaivism and Vaishnavism, respectively, have understandably developed something of a mutual rivalry. Efforts to identify each god as the antithesis of the other has lead to noticeable juxtapositions in their characters: while Shiva is the ascetic connected with a spate of macabre images, Vishnu is the bejeweled monarch, ruling over the universe as a king would a society. Further, myths arising out of each tradition will often recount similar tales involving the exploits of both gods, often presenting their chosen deity as superior. The Siva Puranas, for instance, do not allow any deity other than Shiva the satisfaction of destroying a demon; however, in the Vaishnava Puranas, Siva is unable to slay any demon without the intervention of Vishnu at the crucial moment[6]. In one such myth, Siva grants the demon Vrka a boon which affords him the ability to kill whomever he touches. Vrka promptly attempts to apply the boon to Parvati and even Shiva himself. Helpless to the conditions of the very boon he had granted, Shiva is forced to rely on Vishnu's aid to save him. Vishnu suggests to Vrka that he test the boon on his own head, insinuating that Shiva is a liar, and Vrka inadvertently kills himself in the process of putting the allegations to test. Similarly, Shaivite mythographers also reinvented or reshaped stories to show how it was in fact Vishnu who was dependent on Shiva. For example, it is sometimes said by Shaivites that it was Shiva who bestowed Vishnu with his all-important weapon, the Sudarsanacakra.

Despite their rivalry, Shiva and Vishnu are sometimes depicted together in the form of the Hari-Hara, a statue of a single figure split down the center into two distinct halves. One half has all the characteristic markings of Vishnu (or Hari) while the other half possesses those of Shiva (Hara). This figure is comparable to the aforementioned Ardhanarisvara, though much less common. Just as in that figure, the Hari-Hara depictions almost always place Shiva on the right hand side, pointing toward his superiority over Vishnu on the relatively inauspicious left.

Worship

Shaivism refers to a cluster of Hindu schools and traditions in which are devoted primarily to the worship of Shiva. Shaivism is practiced widely throughout India, and varies greatly in both philosophy and practice based upon distinct regional variations. With approxiamately 200 million adherents, Shaivism is one of the most prominent communities within Hinduism, second only to Vaishnavism [7]

Some of the most prominent Shaivite schools include:

- The Pashupatas (Sanskrit: Pāśupatas), one of the oldest named Shaivite sects, wielded great influence over South Indian Shaivism from the 7th to 14th centuries. The sect is well known because of two surviving texts, the Ganakarika and the Pasupata Sutra, each of which put forth the dualistic distinction between souls (pashu), God (pati) and the physical word (pāsha), which become a cornerstone of various traditions that followed, especially Shaiva Siddhanta.

- The Kapalikas centred around bhakti devotion to Bhairava. Recapitulating the mythology of Bhairava themselves, Kapalikas based their religious lives upon penance for the murder of Brahmins in order to accumulate merit, and so they too carried skulls with them as they wandered from town to town. Members of this sect were linked with a number of bizarre ritual practices, including meat-eating, intoxication, orgies, and even cannibalism, all in an effort to satisfy the horrifying god to whom they were devoted.

- The Kalamukhas (or "black-faced"), meanwhile, are often closely linked to the Kapalikas, although their practices were more congruent with the Bramanical tradition than opposed to it. Information on this sect, though limited, suggests that the Kalamukhas existed in mathas, monastic organizations centered around a temple.

- The Nayanars, an exalted group comprised of sixty-three poet-saints that arose in South India during the seventh century C.E., were among the first proponents of the vernacular bhakti tradition. The hymns penned by these saints communicate deep emotional love for Shiva in his personal form.

- Kashmir Shaivism is a name given to a number of diverse and influential sects which thrived in the northern Indian region of Kashmir during the second half of the ninth century CE. Among these groups were the dualistic Shaiva Siddhantas (see below) and a number of monistic traditions, such as those of the Trika and Krama.

- Shiva Siddhanta is a tradition which seems to have originated as early as the sixth century CE in Kashmir and central India,[8] although it also flourished in South India. Between the eleventh or twelfth centuries CE Shaiva Siddhanta was well-established in this area of the subcontinent, particularly in Tamil Nadu.[9] Shaiva Siddhanta upholds the older Pashupata distinction between three eternal substrates: souls, God, and the physical world, and is still widely practiced today.

- Virashaivism ("heroic Shaivism", whose followers are know as the Lingayats or "bearers of the linga") is a reformist Shaivite sect with approxiamately six million adherents located in the South India state of Karnataka.[10] The movement originated along the border regions of Karnataka and Maharashtra in the mid-12th century. As is evident by their alternative moniker, the linga represents the most important religious symbol for this group, and so members must pay homage to it at least twice every day.

Temples

There are innumerable temples and shrines dedicated to Shiva throughout India, each of which is based upon the instructions for temple construction delineated in one of the twenty-eight volumes which make up the Agamas. The architecture and layout, locations of the images, and directions for methods of worship are all prescribed in the chosen Agama, and no deviation from these directions is permitted. Shiva temples have a number of common features, including a tall multi-storied gopuram, which rises tower-like at the temple entrance and is enclosed within a high wall. A focal linga usually resides deep within the temple compound of buildings, courtyards and gardens; the linga and the special structure that houses it are placed in such a way that they face the compound entrance directly. Only the guru may enter this sanctum sanctorum. Every Siva temple has at least one path encircling its sacred space, around which a procession may walk as part of the devotional service. A stone statue of Siva as Teacher, the Dakshinamurthy, faces south. These images and symbols of Shiva are commonly accompanied by icons dedicated to those closely related to him in his mythology, including sons Ganesha and Skandha, as well as Śakti with whom he is often depicted as Ardhanarishvara.

Ritual

Shivacharyas ("teachers of Shiva") conduct Shiva worship services. The usual service proceeds with the anointing of the image of the Shiva with oil, water, milk, ghee, honey, curd, sandalwood paste, and a number of other substances. Immediatly afterward, the icon of Shiva is showered with blossoms, then adorned with jewels and flower garlands. Incense is burned, and a food offering is made, typically consisting of rice. After camphor and lamps of various designs are lit and presented to the image of the deity, the burning camphor is carried to the entirety of the congregation. The worshippers reverentially place their palms over the flame before placing them over their eyes, a gesture signifying the idea that devotion to Shiva is as precious to the worshipper as his or her own sight. Finally, sacred ash and powdered turmeric mixed with slaked lime are distributed into the upraised palms of the worshippers, who touch this mixture to their foreheads. The worshippers then progress along the path of circumambulation around the diety at least once before prostrating in prayer to the sacrosanct linga, all the while singing and reciting verses from the holy texts.

Shiva Ratri

The foremost festival dedicated to Shiva is that of Shiva Ratri, literally the "night of Shiva", which celebrates the day the god drank the Halahala poison, thereby saving all of humanity. The event takes place on fourteenth day of the waning moon in the month of Falgun (February- March), and, on this day, Shaivite Temples are elaborately decorated, with hordes of devotees lining up to offer obeisances to Shiva.[11] In honour of Shiva's insouciant attitude toward the phenomenal world, for this occassion devotees become intoxicated by a drink called Thandai made from cannabis, almonds, and milk. This beverage is consumed as prasad while singing devotional hymns and dancing to the rhythm of drums. [12]

Significance

In terms of the theologically diverse Hindu tradition, Shiva is the great synthesizer, in that he has subsumed the traits and traditions of many, multifarious deities. His highly personalistic form serves to represent the manifold and malleable nature of divinity, rather than a static, impersonal force pervading the universe. What results is a rich, vibrant, and truly human god, marked by seemingly paradoxical elements of his character. For instance, in his mythological connections with Sati and Parvati, Shiva illustrates not only the power of asceticism, but also the equal necessity of physical love and domestic responsibility. Further, in his aspects as Rudra and Bhairava he provides one of the most obvious examples of Rudolph Otto's mysterium tremendum fascinans — that is, he not only represents the benevolent aspects typical of a typical creator god, but also the equally important fear-inspiring elements of a cosmic destroyer. As such, Shiva's very character is defined by a process of reconciliation of opposites, and so he can be thought of the divine embodiment of a continual dialectical synthesis.

Notes

- ↑ Gavin Flood, An Introduction to Hinduism. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 28-29.

- ↑ Goldberg, 55.

- ↑ Lorenzen, 85.

- ↑ Courtright, 5.

- ↑ Brown, 77.

- ↑ Klostermaier, 151.

- ↑ The World Almanac & Book of Facts 1998 (K-111 Reference Corp.: Mahwah, NJ), pg. 654.

- ↑ Keay, 62.

- ↑ Flood (2003), 217.

- ↑ Padoux, "Virashaivas", 12.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bhandarkar, Ramakrishna Gopal. Vaisnavism, Śaivism, and Minor Religious Systems, Third AES reprint edition. 1913 New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, 1995. ISBN 81-206-0122-X

- Brown, Robert L. Ganesh: Studies of an Asian God. Albany: State University of New York, 1991. ISBN 0791406571

- Chakravarti, Mahadev. The Concept of Rudra-Shiva Through the Ages. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1986. ISBN 8120800532

- Courtright, Paul B. Gaṇeśa: Lord of Obstacles, Lord of Beginnings. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. ISBN 0195057422

- Doniger, Wendy. Asceticism and eroticism in the mythology of Śiva. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973. ISBN 0197135730

- Flood, Gavin. An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0521438780

- Flood, Gavin (Editor). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2003. ISBN 1-4051-3251-5

- Goldberg, Ellen. The Lord Who Is Half Woman: Ardhanarisvara in Indian and Feminist Perspective. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0791453261

- Keay, John. India: A History. New York: Grove Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0

- Klostermaier, Klaus K. Hinduism: A Short History. Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-85168-213-9

- Lorenzen, David. The Kāpālikas and Kālāmukhas: Two Lost Saivite Sects. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1972. ISBN 81-208-0708-1

- Mukundan, A.P. Unto Shiva Consciousness. New Delhi: Samkaleen Prakashan, 1992. ISBN 81-7083-109-1

- Padoux, Andre. "Saivism: Virasaivas." Encyclopedia of Religion. Edited by Mercia Eliade. New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1987, 12-13. ISBN 0029098505