Difference between revisions of "Shimon bar Yochai" - New World Encyclopedia

m |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (40 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Image:GraveOfRabbiSimeonBarYochaiOnLagBOmer.jpg|thumb|250px|The grave of | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} |

| + | [[Image:GraveOfRabbiSimeonBarYochaiOnLagBOmer.jpg|thumb|250px|The grave of Shimon bar Yochai in [[Meron]], [[Israel]], on the Jewish Holiday of [[Lag Ba'Omer]].]] | ||

| + | '''Shimon bar Yochai''', ([[Aramaic language|Aramaic]]: רבן שמעון בר יוחאי), also known as '''Simeon son of Yohai''', or '''Rashbi''' (from '''Ra'''bbi '''Sh'''imeon '''b'''ar '''Y'''ochai.), was a famous ancient [[rabbi]] and one of the greatest of the [[tannaim]] in the second century CE. He was an eminent disciple of [[Rabbi Akiva]] and is often quoted in the [[Talmud]], the [[Mishnah]], and other Jewish texts. To him were attributed the exegetical works called ''[[Sifre]]'' and ''[[Mekhilta de-Rabbi Shimon|Mekhilta]]''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A noted patriot, who, like Akiva, ran afoul of the Roman authorities, Shimon bar Yochai is said to have spent 13 years living in a cave with his son to escape a death sentence against him. After coming out of hiding he became famous for cleansing the city of [[Tiberias]] of its ritual impurity. He soon developed a reputation as a powerful [[miracle]]-worker and, according to legend, was sent to [[Rome]] as an envoy, where he [[exorcism|exorcised]] from the emperor's daughter a [[demon]] who had obligingly entered the lady to enable Rabbi Shimon to effect his miracle. | ||

| + | {{Toc}} | ||

| + | Also known as a great mystic, later tradition made him the author of the ''[[Zohar]]'', the most important work of the [[Kabbalah]]. His son, Rabbi [[Eleazar ben Simon (tanna)|Eleazar ben Simon]] was also a noted scholar and one of the tannaim. One of his pupils was [[Judah haNasi]], the compiler of the [[Mishnah]]. When the Talmud attributes a teaching to "Rabbi Shimon" (or Simeon) without specifying which Shimon is meant, it refers to Shimon bar Yochai. | ||

| − | |||

==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

| + | ===Student of Akiva=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Akiba ben joseph.jpg|thumb|110px|Rabbi [[Akiva]]]] | ||

| − | Shimon | + | Shimon was one of the principal pupils of Rabbi [[Akiva]], the greatest of the second generation [[tannaim]]. He seems to have studied previously under [[Gamaliel II]] (Ber. 28a) and [[Joshua ben Hananiah]] and is traditionally believed to have been the cause of the quarrel that broke out between these two leading scholars. He studied with Akiva for 13 years and was one of only two disciples, together with [[Rabbi Meïr]], to be ordained by Akiva. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Shimon stayed for some time in the city of [[Sidon]], where one of many legendary episodes in his life occurred. A man and his wife who had no children after ten years of marriage came to him to secure a divorce. Observing that they still loved each other, but admitting that the request was allowed by Jewish law, Simeon advised them that their separation should be marked by a feast, just as their marriage had been. Not only did the couple remain together as a result, but Shimon's blessing on their continued union moved [[God]] to grant them a child (Pesiḳ. xxii. 147a). | |

| − | + | Shimon's love for his great teacher was profound. When Akiva was imprisoned by [[Hadrian]] after the [[Bar Kochba]] revolt, Shimon found a way to enter the prison to be instructed by him (Pes. 112a). Shimon shared Akiva's patriotic zeal in opposition to Roman rule. When another rabbi spoke in favor of the Roman government, Shimon replied that their institutions were self-serving and essentially wicked. When his words were reported to the Roman governor, Shimon was sentenced to death. | |

| − | + | ===In hiding and ministry in Tiberias=== | |

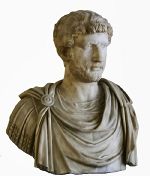

| + | [[Image:Hadrien-ven.JPG|thumb|150px|left|Shimon and his son were forced into hiding during the reign of Emperor [[Hadrian]] after the [[Bar Kochba]] revolt]] | ||

| − | + | To avoid capture, Shimon was compelled to seek refuge in a cave for an extended period (Yer. Sheb. ix. 38d; Shab. 33b; Pesiḳ. 88b; Gen. R. lxxix. 6). In one version of the story of this time, he and his son Eleazar hid in a cavern for 13 years, living on dates and the fruit of the carob-tree, and their whole bodies becoming covered with painful boils. Seeing a bird that had repeatedly escaped a trapper's net, Simeon took this as a sign that God would bless their escape. Outside the cavern, they heard a voice from heaven say, "You are free!" They accordingly continued on their way. Shimon then bathed in the warm springs of [[Tiberias]], which rid him of the skin disease contracted in the cavern. In another version of the story, the two mean left their hiding place after the prophet [[Elijah]] announced to them the death of the emperor and the consequent annulment of the sentence of death against them. | |

| − | + | [[Image:Israel outline north haifa.png|thumb|250px|[[Tiberias]] is shown on the western shore of the [[Sea of Galilee]]; Shimon's later center of activity in Meron is near the northern city of [[Safed]].]] | |

| − | + | Tiberias had been built by [[Herod Antipas]] on a site where there were many tombs, the exact locations of which had been lost. The town therefore had been regarded as unclean by many pious Jews. Resolving to remove the cause of the uncleanness, Shimon planted [[lupines]], a [[legume]] which was a popular food in Roman times, in all the suspected places, and wherever they did not take root he knew that a tomb was underneath. The bodies were then removed and entombed elsewhere, and the town was pronounced ritually clean. | |

| − | + | Shimon was said to possess fearful prophetic powers. For example, when he observed people neglecting the [[Torah]], he smote them by his glances. One of the victims of Shimon's wrath was his former pupil, Judah ben Gerim, who had earlier informed the Romans of his teacher's allegedly treasonous remarks. To discredit Shimon a certain [[Samaritan]] secretly replaced one of the bodies that had been removed from Tiberias. Shimon learned of the deed through the power of the [[Holy Spirit]] and declared: "Let what is above go down, and what is below come up." Legend holds that the Samaritan soon died and was buried, while a schoolteacher who mocked Shimon for his declaration was turned into a heap of bones. | |

| − | + | ===Meron and later life=== | |

| − | + | [[Image:Asmodeus.jpg|thumb|In one version of his story, Shimon bar Yochai mobilized the demon [[Asmodeus]] to help him gain a boon from the Roman emperor.]] | |

| − | + | Shimon later settled in Meron, near present-day [[Safed]]. He is also said to have established a flourishing school at Tekoa, probably in [[Galilee]] rather than the biblical town of the same name in the territory of [[tribe of Judah|Judah]], and thought by some to be identical with Meron. | |

| − | + | Accompanied by Rabbi Eleazar ben Jose, near the end of his life Shimon was sent to Rome to petition the emperor for the abolition certain anti-Jewish laws (Me'i. 17b). Shimon's success in this mission, like many of his accomplishments, was said to have been due to a miracle. On his way to Rome he was met by the [[demon]] Ben Temalion (alternatively [[Asmodeus]]), who, not being such an evil spirit after all, offered his assistance. The two agreed, and the demon then possessed the emperor's daughter, enabling Shimon to [[exorcism|exorcise]] it when he arrived at the Roman court. The emperor then took Shimon into his treasure-house, leaving him to choose his own reward. Shimon found there the offensive decree against the Jews, which he took as his reward and later tore into pieces. | |

| − | + | Among Shimon's pupils were [[Judah ha-Nasi]], the last of the great [[tannaim]] and redactor of the [[Mishnah]]. Shimon died at Meron, where his grave became a site of pilgrimage and remains so to this day. | |

| − | + | ==Teachings== | |

| + | [[Image:Talmud Babli bokhylle.jpg|thumb|Shimon bar Yochai is one of the most frequently quoted rabbis of the [[Talmud]].]] | ||

| + | Shimon bar Yochai [[halakha|legal opinions]] are very numerous and can be found in most of the treatises of the [[Talmud]]. Although he admired his teacher [[Akiva]], he declared his own interpretations to be superior (Sifre, Deut. 31; R. H. 18b). Nor did he refrain from criticizing the [[tannaim]] of the preceding generations (comp. Tosef., Oh. iii. 8, xv. 11). | ||

| − | + | Shimon displayed a notable sense of spiritual self-confidence. He said, for instance that if there were only two people allowed to enter heaven, he and his son would be the two (Suk. 45b; Sanh. 97b). He is also credited with saying that, together with his son and the ancient King [[Jotham]] of Judah (in alternate versions, [[Abraham]] or [[Ahijah of Shiloh]] are mentioned instead) he would be able to free the world from God's judgment (Suk. l.c.; comp. Yer. Ber. ix. 13d and Gen. R. xxxv. 3). | |

| − | + | A particular characteristic of Shimon's teaching was his concern to express the underlying reasons for various biblical and [[halakha|halakhic]] commands. This sometimes resulted in a modification of the command in question. For example, in the prohibition against taking a widow's raiment in pledge (Deut. 24:17) said that the reason for such a prohibition was that if such a pledge were taken it would be necessary to return it every evening, and going to the widow's home every morning and evening might compromise her reputation. Consequently, he declared the prohibition applies only in the case of a poor widow, since one who is rich would not need to have the garment returned in the evening (B. M. l.c.). | |

| − | + | Because of his association with this form of interpretation, Shimon's contemporaries often appealed to him when they wanted to know the reason for certain [[halakha|halakot]] (Tosef., Zeb. i. 8). He also compiled a number of general rules summarizing various types of commandments (Bik. iii. 10; Zeb. 119b et al.). His approach was systematic and clear in its expression (Sheb. ii. 3; 'Er. 104b). Although was dogmatic in his halakhic decisions, where there was a doubt as to which of two courses should be followed he admitted the legality of either course (Yeb. iii. 9). He is regarded as being the author the halakhic exegetical works known as ''[[Sifre]]'' and ''[[Mekhilta de-Rabbi Shimon|Mekhilta]]''. | |

| + | In addition to his prominence in the [[Mishnah]] and the [[Talmud]], Shimon is also a major figure in the non-legal texts that constitute the [[Aggadah]]. Many of his sayings there relate to the study of the [[Torah]], which he held should be the main object of man's life. He placed greate stress on the importance of prayer, and particularly on the reading of the ''[[Shema]]'', However, he also declared prayer must not interrupt the study of the Torah (Yer. Ḥag. ii. 77a). | ||

| + | Shimon believed, however, that more essential to a true spiritual life than Torah study and prayer is ethical action. He recognized that careful study of the Torah and of providing a livelihood at the same time may prevent those without wealth from attain the "crown" of scholarship. (Mek., Beshallaḥ, Wayeḥi, 1, Wayassa', 2). "There are three crowns," he says, "but the crown of a good name mounts above them all." | ||

| − | + | Simeon viewed God as willing to forgive those who truly repented of the sins. "So great is the power of repentance," he said, "that a man who has been during his lifetime very wicked, if he repent toward the end, is considered a perfectly righteous man" (Tosef., Ḳid. i. 14; Ḳid. 40b; Cant. R. v. 16). He was particularly decried the sin of haughtiness, which he said is like [[idolatry]] (Soṭah 4b). "One should rather throw himself into a burning furnace than shame a neighbor in public," he declared (Ber. 43b). He also denounced the crimes of usury, deceitful dealing, and disturbing domestic peace (Yer. B. M. 10d; B. M. 58b; Lev. R. ix.). | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Shimon's patriotism, developed through the horrors of the massacre of countless Jewish during the [[Bar Kochaba]] revolt, led him to express general animosity toward the [[Gentile]]s: "The best of the heathen merits death," he declared." Nor was he a defender of the general character of women: "The most pious of women is prone to sorcery." (Yer. Ḳid. iv. 66c; Massek. Soferim xv. 10; comp. Mek., Beshallaḥ, Wayeḥi, 1, and Tan., Wayera, 20). However, he apparently saw the Persians as possible liberators of the Jews. Probably alluding to the Parthian war which broke out in the time of [[Antoninus Pius]], he said: "If you see a Persian horse tied in [[Palestine]], then (you may) hope for the arrival of the [[Messiah]]." (Cant. R. viii. 10; Lam. R. i. 13) | |

| − | + | Shimon combined his rationalism in [[halakha]] with a certain [[mysticism]] in his non-legal teachings, as well as in his personal practice. He spoke of a magic sword, on which the [[names of God in Judaism|Name of God]] was inscribed, being given by God to [[Moses]] on [[Mount Sinai]] (Midr. Teh. to Ps. xc. 2). He also ascribed all kinds of miraculous powers to Moses beyond those mentioned in the Torah (Me'i. 17b; Sanh. 97b). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| + | On account of his exceptional piety and continual study of the [[Torah]], Shimon bar Yochai came to be seen as one of those [[Tzadik|righteous men]] whose merit preserves the world (Yer. Ber. l.c.). After his death, he appeared to many Jewish saints in their visions (B. M. 84b; Ket. 77b; Sanh. 98a). Thus his name became connected with mystic lore, and he became a chief authority for the the [[Kaballah]]. Centuries later, the [[Zohar]] first appeared under the name of ''Midrash de-Rabbi Shim'on ben Yoḥai''. | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Rashbi.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Site of the cave in which Shimon bar Yohai is believed to be buried.]] | |

| − | + | Two other apocryphal tests are also ascribed to him. The first is entitled ''Nistarot de-R. Shim'on b. Yoḥai''; the second, ''Tefillat R. Shim'on b. Yoḥai''. The main point of these texts is that while Shimon was hidden in the cavern, he fasted 40 days and prayed to God to rescue Israel from such persecutions. A powerful angel revealed to him the future, announcing even the various Muslim rulers, the last one of whom would perish at the hands of the [[Messiah]]. The chief characters are Armilus, a type of [[Antichrist]], and the three Messiahs descended from the [[Joseph son of Jacob|Joseph]], [[Ephraim]], and [[David]], respectively. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The holiday of [[Lag Ba'omer]] is traditionally regarded as also being the anniversary Shimon bar Yochai's death. Unlike many other such commemorations, it is seen as day of celebration. Associated with the mystical tradition of nearby [[Safed]], pilgrims visit his burial place with torches, songs, and feasting, often involving many thousands of people. This celebration is said have been a specific request by Rabbi Shimon to his students. It is a custom at the Meron celebrations, dating from the time of Rabbi [[Isaac Luria]] in the [[Middle Ages]], that three-year-old boys are given their first haircuts, while their parents distribute wine and sweets. | |

| − | While it is widely accepted that Rabbi Shimon and his son were buried somewhere on Mount Meron, | + | While it is widely accepted that Rabbi Shimon and his son were buried somewhere on Mount Meron, the building generally accepted as being his grave is an arched structure typical of crusader architecture. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Tannaim]] |

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Zohar]] |

| − | + | *[[Akiva]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | *Duker, Jonathan. ''The Spirits Behind the Law: The Talmudic Scholars''. Jerusalem: Urim, 2007. ISBN 9657108977 | ||

| + | *Green, William Scott. ''Persons and Institutions in Early Rabbinic Judaism.'' Brown Judaic studies, no. 3. Missoula, Mont: Published by Scholars Press for Brown University, 1977. ISBN 9780891301318 | ||

| + | *Krohn, Genendel, and Tirtsah Peleg. ''The Story of Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai''. Jerusalem: Feldheim, 2006. (Juvenile) ISBN 9781583308868 | ||

| + | *Moore, George Foot.'' Judaism in the First Centuries of the Christian Era: The Age of Tannaim.'' Peabody, Mass: Hendrickson Publishers, 1997. ISBN 9781565632868 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved January 27, 2023. | |

* [http://www.chabad.org/search/keyword.asp?kid=1417 Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai] chabad.org | * [http://www.chabad.org/search/keyword.asp?kid=1417 Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai] chabad.org | ||

| − | |||

*[http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=774&letter=S SIMEON BEN YOḤAI] in the Jewish Encyclopedia | *[http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=774&letter=S SIMEON BEN YOḤAI] in the Jewish Encyclopedia | ||

{{Mishnah tree}} | {{Mishnah tree}} | ||

Latest revision as of 14:13, 27 January 2023

Shimon bar Yochai, (Aramaic: רבן שמעון בר יוחאי), also known as Simeon son of Yohai, or Rashbi (from Rabbi Shimeon bar Yochai.), was a famous ancient rabbi and one of the greatest of the tannaim in the second century CE. He was an eminent disciple of Rabbi Akiva and is often quoted in the Talmud, the Mishnah, and other Jewish texts. To him were attributed the exegetical works called Sifre and Mekhilta.

A noted patriot, who, like Akiva, ran afoul of the Roman authorities, Shimon bar Yochai is said to have spent 13 years living in a cave with his son to escape a death sentence against him. After coming out of hiding he became famous for cleansing the city of Tiberias of its ritual impurity. He soon developed a reputation as a powerful miracle-worker and, according to legend, was sent to Rome as an envoy, where he exorcised from the emperor's daughter a demon who had obligingly entered the lady to enable Rabbi Shimon to effect his miracle.

Also known as a great mystic, later tradition made him the author of the Zohar, the most important work of the Kabbalah. His son, Rabbi Eleazar ben Simon was also a noted scholar and one of the tannaim. One of his pupils was Judah haNasi, the compiler of the Mishnah. When the Talmud attributes a teaching to "Rabbi Shimon" (or Simeon) without specifying which Shimon is meant, it refers to Shimon bar Yochai.

Biography

Student of Akiva

Shimon was one of the principal pupils of Rabbi Akiva, the greatest of the second generation tannaim. He seems to have studied previously under Gamaliel II (Ber. 28a) and Joshua ben Hananiah and is traditionally believed to have been the cause of the quarrel that broke out between these two leading scholars. He studied with Akiva for 13 years and was one of only two disciples, together with Rabbi Meïr, to be ordained by Akiva.

Shimon stayed for some time in the city of Sidon, where one of many legendary episodes in his life occurred. A man and his wife who had no children after ten years of marriage came to him to secure a divorce. Observing that they still loved each other, but admitting that the request was allowed by Jewish law, Simeon advised them that their separation should be marked by a feast, just as their marriage had been. Not only did the couple remain together as a result, but Shimon's blessing on their continued union moved God to grant them a child (Pesiḳ. xxii. 147a).

Shimon's love for his great teacher was profound. When Akiva was imprisoned by Hadrian after the Bar Kochba revolt, Shimon found a way to enter the prison to be instructed by him (Pes. 112a). Shimon shared Akiva's patriotic zeal in opposition to Roman rule. When another rabbi spoke in favor of the Roman government, Shimon replied that their institutions were self-serving and essentially wicked. When his words were reported to the Roman governor, Shimon was sentenced to death.

In hiding and ministry in Tiberias

To avoid capture, Shimon was compelled to seek refuge in a cave for an extended period (Yer. Sheb. ix. 38d; Shab. 33b; Pesiḳ. 88b; Gen. R. lxxix. 6). In one version of the story of this time, he and his son Eleazar hid in a cavern for 13 years, living on dates and the fruit of the carob-tree, and their whole bodies becoming covered with painful boils. Seeing a bird that had repeatedly escaped a trapper's net, Simeon took this as a sign that God would bless their escape. Outside the cavern, they heard a voice from heaven say, "You are free!" They accordingly continued on their way. Shimon then bathed in the warm springs of Tiberias, which rid him of the skin disease contracted in the cavern. In another version of the story, the two mean left their hiding place after the prophet Elijah announced to them the death of the emperor and the consequent annulment of the sentence of death against them.

Tiberias had been built by Herod Antipas on a site where there were many tombs, the exact locations of which had been lost. The town therefore had been regarded as unclean by many pious Jews. Resolving to remove the cause of the uncleanness, Shimon planted lupines, a legume which was a popular food in Roman times, in all the suspected places, and wherever they did not take root he knew that a tomb was underneath. The bodies were then removed and entombed elsewhere, and the town was pronounced ritually clean.

Shimon was said to possess fearful prophetic powers. For example, when he observed people neglecting the Torah, he smote them by his glances. One of the victims of Shimon's wrath was his former pupil, Judah ben Gerim, who had earlier informed the Romans of his teacher's allegedly treasonous remarks. To discredit Shimon a certain Samaritan secretly replaced one of the bodies that had been removed from Tiberias. Shimon learned of the deed through the power of the Holy Spirit and declared: "Let what is above go down, and what is below come up." Legend holds that the Samaritan soon died and was buried, while a schoolteacher who mocked Shimon for his declaration was turned into a heap of bones.

Meron and later life

Shimon later settled in Meron, near present-day Safed. He is also said to have established a flourishing school at Tekoa, probably in Galilee rather than the biblical town of the same name in the territory of Judah, and thought by some to be identical with Meron.

Accompanied by Rabbi Eleazar ben Jose, near the end of his life Shimon was sent to Rome to petition the emperor for the abolition certain anti-Jewish laws (Me'i. 17b). Shimon's success in this mission, like many of his accomplishments, was said to have been due to a miracle. On his way to Rome he was met by the demon Ben Temalion (alternatively Asmodeus), who, not being such an evil spirit after all, offered his assistance. The two agreed, and the demon then possessed the emperor's daughter, enabling Shimon to exorcise it when he arrived at the Roman court. The emperor then took Shimon into his treasure-house, leaving him to choose his own reward. Shimon found there the offensive decree against the Jews, which he took as his reward and later tore into pieces.

Among Shimon's pupils were Judah ha-Nasi, the last of the great tannaim and redactor of the Mishnah. Shimon died at Meron, where his grave became a site of pilgrimage and remains so to this day.

Teachings

Shimon bar Yochai legal opinions are very numerous and can be found in most of the treatises of the Talmud. Although he admired his teacher Akiva, he declared his own interpretations to be superior (Sifre, Deut. 31; R. H. 18b). Nor did he refrain from criticizing the tannaim of the preceding generations (comp. Tosef., Oh. iii. 8, xv. 11).

Shimon displayed a notable sense of spiritual self-confidence. He said, for instance that if there were only two people allowed to enter heaven, he and his son would be the two (Suk. 45b; Sanh. 97b). He is also credited with saying that, together with his son and the ancient King Jotham of Judah (in alternate versions, Abraham or Ahijah of Shiloh are mentioned instead) he would be able to free the world from God's judgment (Suk. l.c.; comp. Yer. Ber. ix. 13d and Gen. R. xxxv. 3).

A particular characteristic of Shimon's teaching was his concern to express the underlying reasons for various biblical and halakhic commands. This sometimes resulted in a modification of the command in question. For example, in the prohibition against taking a widow's raiment in pledge (Deut. 24:17) said that the reason for such a prohibition was that if such a pledge were taken it would be necessary to return it every evening, and going to the widow's home every morning and evening might compromise her reputation. Consequently, he declared the prohibition applies only in the case of a poor widow, since one who is rich would not need to have the garment returned in the evening (B. M. l.c.).

Because of his association with this form of interpretation, Shimon's contemporaries often appealed to him when they wanted to know the reason for certain halakot (Tosef., Zeb. i. 8). He also compiled a number of general rules summarizing various types of commandments (Bik. iii. 10; Zeb. 119b et al.). His approach was systematic and clear in its expression (Sheb. ii. 3; 'Er. 104b). Although was dogmatic in his halakhic decisions, where there was a doubt as to which of two courses should be followed he admitted the legality of either course (Yeb. iii. 9). He is regarded as being the author the halakhic exegetical works known as Sifre and Mekhilta.

In addition to his prominence in the Mishnah and the Talmud, Shimon is also a major figure in the non-legal texts that constitute the Aggadah. Many of his sayings there relate to the study of the Torah, which he held should be the main object of man's life. He placed greate stress on the importance of prayer, and particularly on the reading of the Shema, However, he also declared prayer must not interrupt the study of the Torah (Yer. Ḥag. ii. 77a).

Shimon believed, however, that more essential to a true spiritual life than Torah study and prayer is ethical action. He recognized that careful study of the Torah and of providing a livelihood at the same time may prevent those without wealth from attain the "crown" of scholarship. (Mek., Beshallaḥ, Wayeḥi, 1, Wayassa', 2). "There are three crowns," he says, "but the crown of a good name mounts above them all."

Simeon viewed God as willing to forgive those who truly repented of the sins. "So great is the power of repentance," he said, "that a man who has been during his lifetime very wicked, if he repent toward the end, is considered a perfectly righteous man" (Tosef., Ḳid. i. 14; Ḳid. 40b; Cant. R. v. 16). He was particularly decried the sin of haughtiness, which he said is like idolatry (Soṭah 4b). "One should rather throw himself into a burning furnace than shame a neighbor in public," he declared (Ber. 43b). He also denounced the crimes of usury, deceitful dealing, and disturbing domestic peace (Yer. B. M. 10d; B. M. 58b; Lev. R. ix.).

Shimon's patriotism, developed through the horrors of the massacre of countless Jewish during the Bar Kochaba revolt, led him to express general animosity toward the Gentiles: "The best of the heathen merits death," he declared." Nor was he a defender of the general character of women: "The most pious of women is prone to sorcery." (Yer. Ḳid. iv. 66c; Massek. Soferim xv. 10; comp. Mek., Beshallaḥ, Wayeḥi, 1, and Tan., Wayera, 20). However, he apparently saw the Persians as possible liberators of the Jews. Probably alluding to the Parthian war which broke out in the time of Antoninus Pius, he said: "If you see a Persian horse tied in Palestine, then (you may) hope for the arrival of the Messiah." (Cant. R. viii. 10; Lam. R. i. 13)

Shimon combined his rationalism in halakha with a certain mysticism in his non-legal teachings, as well as in his personal practice. He spoke of a magic sword, on which the Name of God was inscribed, being given by God to Moses on Mount Sinai (Midr. Teh. to Ps. xc. 2). He also ascribed all kinds of miraculous powers to Moses beyond those mentioned in the Torah (Me'i. 17b; Sanh. 97b).

Legacy

On account of his exceptional piety and continual study of the Torah, Shimon bar Yochai came to be seen as one of those righteous men whose merit preserves the world (Yer. Ber. l.c.). After his death, he appeared to many Jewish saints in their visions (B. M. 84b; Ket. 77b; Sanh. 98a). Thus his name became connected with mystic lore, and he became a chief authority for the the Kaballah. Centuries later, the Zohar first appeared under the name of Midrash de-Rabbi Shim'on ben Yoḥai.

Two other apocryphal tests are also ascribed to him. The first is entitled Nistarot de-R. Shim'on b. Yoḥai; the second, Tefillat R. Shim'on b. Yoḥai. The main point of these texts is that while Shimon was hidden in the cavern, he fasted 40 days and prayed to God to rescue Israel from such persecutions. A powerful angel revealed to him the future, announcing even the various Muslim rulers, the last one of whom would perish at the hands of the Messiah. The chief characters are Armilus, a type of Antichrist, and the three Messiahs descended from the Joseph, Ephraim, and David, respectively.

The holiday of Lag Ba'omer is traditionally regarded as also being the anniversary Shimon bar Yochai's death. Unlike many other such commemorations, it is seen as day of celebration. Associated with the mystical tradition of nearby Safed, pilgrims visit his burial place with torches, songs, and feasting, often involving many thousands of people. This celebration is said have been a specific request by Rabbi Shimon to his students. It is a custom at the Meron celebrations, dating from the time of Rabbi Isaac Luria in the Middle Ages, that three-year-old boys are given their first haircuts, while their parents distribute wine and sweets.

While it is widely accepted that Rabbi Shimon and his son were buried somewhere on Mount Meron, the building generally accepted as being his grave is an arched structure typical of crusader architecture.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Duker, Jonathan. The Spirits Behind the Law: The Talmudic Scholars. Jerusalem: Urim, 2007. ISBN 9657108977

- Green, William Scott. Persons and Institutions in Early Rabbinic Judaism. Brown Judaic studies, no. 3. Missoula, Mont: Published by Scholars Press for Brown University, 1977. ISBN 9780891301318

- Krohn, Genendel, and Tirtsah Peleg. The Story of Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai. Jerusalem: Feldheim, 2006. (Juvenile) ISBN 9781583308868

- Moore, George Foot. Judaism in the First Centuries of the Christian Era: The Age of Tannaim. Peabody, Mass: Hendrickson Publishers, 1997. ISBN 9781565632868

External links

All links retrieved January 27, 2023.

- Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai chabad.org

- SIMEON BEN YOḤAI in the Jewish Encyclopedia

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.