Difference between revisions of "Rosetta Stone" - New World Encyclopedia

m |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[[Category:Linguistics]] | [[Category:Linguistics]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

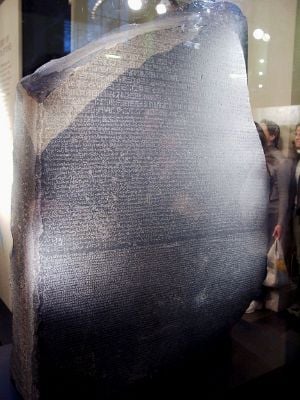

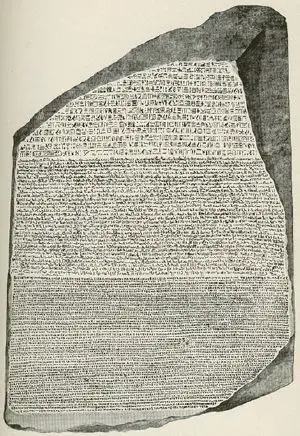

[[Image:rosetta stone.jpg|thumb|right|The Rosetta Stone in the British Museum]] | [[Image:rosetta stone.jpg|thumb|right|The Rosetta Stone in the British Museum]] | ||

| Line 72: | Line 70: | ||

In November 2005, the British Museum sent him a replica of the stone.<ref>{{cite news|title = The rose of the Nile|publisher = [[Al-Ahram Weekly]]|date=[[2005-11-30]]|url = http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2005/770/he1.htm|accessdate = 2006-10-06}}</ref> | In November 2005, the British Museum sent him a replica of the stone.<ref>{{cite news|title = The rose of the Nile|publisher = [[Al-Ahram Weekly]]|date=[[2005-11-30]]|url = http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2005/770/he1.htm|accessdate = 2006-10-06}}</ref> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 03:01, 28 November 2006

The Rosetta Stone is an ancient stele inscribed with the same passage of writing in two Egyptian language scripts and in classical Greek. It was created in 196 BC, discovered by the French in 1799, and translated in 1822 by the Frenchman Jean-François Champollion. Comparative translation of the stone assisted in understanding many previously undecipherable examples of hieroglyphic writing.

The Stone is 114.4 cm high at its tallest point, 72.3 cm wide, and 27.9 cm thick. (45.04 in. high, 28.5 in. wide, 10.9 in. thick). Weighing approximately 1,676 pounds, it was originally thought to be granite or basalt but is currently described as granodiorite. It is dark grey-pinkish in color.

History

Creation of the Stone

Ptolemy V was the 5th ruler of the Hellenistic Ptolemaic Dynasty, which ruled Egypt from 305 BC to 30 BC. His rule began when he was five years old, and thus much of the ruling of Egypt was done by Regents and royal priests. These priests continued the precedent set by Ptolemy III (whose decree appears on the Stone of Canopus) of issuing decrees to the populace, in order to maintain support for the dynasty. They had the decrees inscribed on stone and erected throughout Egypt. The Rosetta Stone is a copy of the decree issued in the city of Memphis.

The Greeks historically supported bilingual practices in territories they occupied. The Rosetta Stone was inscribed with three scripts so that it could be read not only by the local populace, but also by visiting priests and government officials. The first script was Hieroglyphic, the script used for religious documents and other important communications. The second was Demotic Egyptian, which was the common script of Egypt. The third was Greek, which was the language of the post-Alexander rulers of Egypt at that time.

The stone displays the same Ptolemaic decree of 196 BC in the three scripts. The Greek part of the Rosetta Stone begins: Basileuontos tou neou kai paralabontos tēn basileian para tou patros... (Greek: Βασιλεύοντος του νέου και παραλαβόντος την βασιλείαν παρά του πατρός...) (The new king, having received the kingship from his father...) It is a decree from Ptolemy V, describing various taxes he repealed (one measured in ardebs (Greek artabai) per aroura), and instructing that statues be erected in temples and that the decree be published in the writing of the words of gods (hieroglyphs), the writing of the people (demotic), and the Wynen (Greek; the word is cognate with Ionian) language.

The Rosetta Stone was included in the third part of a series of three decrees, the first from Ptolemy III (the Decree of Canopus), the second from Ptolemy IV (The Memphis Stele), and the third from Ptolemy V.

There are approximately two copies of the Stone of Canopus, two of the Memphis Stele (one imperfect) and two and a half copies of the text of the Rosetta Stone, including the Nubayrah Stele and a pyramid wall inscription with "edits", or scene replacements, completed by subsequent scribes.

The Three-Stone Series

Multiple copies of the Ptolemaic Decrees were erected in multiple temple courtyards, as specified in the text of the decrees. The Stele of Nubayrah, found early 1880's, and the text engraved in the Temple of Philae contain the same message as the Rosetta Stone. The Stele of Nubayrah was used to complete missing Rosetta Stone lines.

Full Text of the Stone

In the reign of the new king, who was Lord of the diadems, great in glory, the stabilizer of Egypt, and also pious in matters relating to the gods, Superior to his adversaries, rectifier of the life of men, Lord of the thirty-year periods like Hephaestus the Great, King like the Sun, the Great King of the Upper and Lower Lands, offspring of the Parent-loving Gods, whom Hephaestus has approved, to whom the Sun has given victory, living image of Zeus, Son of the Sun, Ptolemy the ever-living, beloved by Ptah;

In the ninth year, when Aëtus, son of Aëtus, was priest of Alexander and of the Savior Gods and the Brother Gods and the Benefactor Gods and the Parent-loving Gods and the God Manifest and Gracious; Pyrrha, the daughter of Philinius, being athlophorus for Bernice Euergetis; Areia, the daughter of Diogenes, being canephorus for Arsinoë Philadelphus; Irene, the daughter of Ptolemy, being priestess of Arsinoë Philopator: on the fourth of the month Xanicus, or according to the Egyptians the eighteenth of Mecheir.

THE DECREE: The high priests and prophets, and those who enter the inner shrine in order to robe the gods, and those who wear the hawks wing, and the sacred scribes, and all the other priests who have assembled at Memphis before the king, from the various temples throughout the country, for the feast of his receiving the kingdom, even that of Ptolemy the ever-living, beloved by Ptah, the God Manifest and Gracious, which he received from his Father, being assembled in the temple in Memphis this day, declared:

Since King Ptolemy, the ever-living, beloved by Ptah, the God Manifest and Gracious, the son of King Ptolemy and Queen Arsinoë, the Parent-loving Gods, has done many benefactions to the temples and to those who dwell in them and also to all those subjects to his rule, being from the beginning a god born of a god and a goddess—like Horus, the son of Isis and Osirus, who came to the help of his Father Osirus—being benevolently disposed toward the gods, has concentrated to the temples revenues both of silver and of grain, and has generously undergone many expenses in order to lead Egypt to prosperity and to establish the temples... the gods have rewarded him with health, victory, power, and all other good things, his sovereignty to continue to him and his children forever.

Modern-era discovery

After Napoleon's 1798 Campaign in Egypt, the French founded an Institut de l'Egypte in Cairo, bringing many scientists and archaeologists to the region.

French Army engineer Captain Pierre-François Bouchard discovered the stone on July 15, 1799, while he was guiding construction works in the Fort Julien near the Egyptian port city of Rosetta (present-day Rashid). He understood its importance and showed it to General Jacques de Menou. They decided to send the artifact to the Institut de l'Égypte, where it arrived in August 1799. The French language newspaper Courrier de l'Egypte announced the find in September 1799.

After Napoleon returned to France in 1799, 167 scholars remained behind along with a defensive force of French troops. French commanders held off British and Ottoman attacks until March 1801, when the British landed on the Aboukir Bay. Scholars carried the Stone from Cairo to Alexandria alongside the troops of de Menou. French troops in Cairo capitulated on June 22 and in Alexandria on August 30.

After the French surrender, a dispute arose over the fate of French archaeological and scientific discoveries in Egypt. French commander de Menou refused to hand over the collections, claiming that they belonged to the Institute. British General John Hely-Hutchinson refused to relieve the city until de Menou would give in. Newly arrived scholars Edward Daniel Clarke and William Richard Hamilton agreed to check the collections in Alexandria and found numerous artifacts French had not revealed.

When Hutchinson claimed all materials as a property of the British Crown, a French scholar Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, said to Clarke and Hamilton that they'd rather burn all their discoveries, ominously referring to the burned Library of Alexandria. Hutchinson finally agreed that items like the biology specimens would be scholars' private property. Menou regarded the stone as his private property and hid it.

How exactly the Stone came to British hands is disputed. Colonel Tomkyns Hilgrove Turner, who escorted the stone to Britain, claimed later that he had personally seized the stone from de Menou and carried it away on a gun carriage. Clarke stated in his memoirs that a French scholar and an officer had quietly given up the stone to him and his companions in a Cairo back street. French scholars departed later with only imprints and plaster casts of the stone.

Turner brought the stone to Britain aboard a captured French frigate L'Egyptienne on February 1802. On March 11 it was presented to the Society of Antiquities. Later it was taken to British Museum, where it has been since. White painted inscriptions on the artifact state "Captured in Egypt by the British Army in 1801" on the left side and "Presented by King George III" on the right.

Translation

In 1814 British Thomas Young finished translating the enchorial (demotic) text, and went on to work on the hieroglyphic alphabet. During the years of 1822–1824, Jean-François Champollion greatly expanded on his work, and he is known as the translator of the Rosetta Stone. Champollion could read both Greek and Coptic language. He was able to figure out what the seven Demotic signs in Coptic were. By looking at how these signs were used in Coptic he was able to work out what they stood for. Then he began tracing these Demotic signs back to hieroglyphic signs. By working out what some hieroglyphs stood for, he could make educated guesses about what the other hieroglyphs stood for.

In 1858, the Philomathean Society of the University of Pennsylvania published the first complete English translation of the Rosetta Stone. Three undergraduate members, Charles R Hale, S Huntington Jones and Henry Morton, made the translation. The translation quickly sold out two editions and was internationally hailed as a monumental work of scholarship. In 1988, the British Museum bestowed the honor of including the Philomathean Rosetta Stone Report in its select bibliography of the most important works ever published on the Rosetta Stone. The Philomathean Society maintains a full-scale cast of the stone in its meeting room at the University of Pennsylvania.

Today

The Rosetta Stone has been exhibited in the British Museum since 1802, with only one break, from 1917–1919. Toward the end of the First World War, in 1917, when the Museum was concerned about heavy bombing in London, they moved it to safety along with other portable, important objects. The Rosetta Stone spent the next two years in a station on the Postal Tube Railway fifty feet below the ground at Holborn.

In July 2003, the Egyptians demanded the return of the Rosetta Stone. Dr. Zahi Hawass, secretary general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities in Cairo, told the press: "If the British want to be remembered, if they want to restore their reputation, they should volunteer to return the Rosetta Stone because it is the icon of our Egyptian identity." In 2005, Hawass was negotiating for a three-month loan, with the eventual goal of a permanent return.[1] [2] In November 2005, the British Museum sent him a replica of the stone.[3]

External links

- The Rosetta Stone in The British Museum

- The translated text in English

- The Finding of The Rosetta Stone

- An account of Napoléon's findings in Egypt

- The 1998 conservation and restoration of The Rosetta Stone at The British Museum

- Champollion's alphabet

- High Resolution Image of the Face

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Charlotte Edwardes and Catherine Milner. "Egypt demands return of the Rosetta Stone", The Daily Telegraph, 2003-07-20. Retrieved 2006-10-05.

- ↑ Henry Huttinger (2005-07-28). Stolen Treasures: Zahi Hawass wants the Rosetta Stone back—among other things. Cairo Magazine. Retrieved 2006-10-06.

- ↑ "The rose of the Nile", Al-Ahram Weekly, 2005-11-30. Retrieved 2006-10-06.

Further reading

- Downs, Jonathan. "Romancing the Stone", History Today, Vol. 56, Issue 5. (May, 2006), pp. 48–54.

- Parkinson, Richard. Cracking Codes: the Rosetta Stone, and Decipherment. Berkeley, CA; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press, 1999 (hardcover, ISBN 0520223063; paperback, ISBN 0520222482); London: British Museum Press, 1999 (paperback, ISBN 0714119164).

- Solé, Robert; Valbelle, Dominique. The Rosetta Stone: The Story of the Decoding of Hieroglyphics. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 2002 (hardcover, ISBN 1568582269).

- Wallis Budge, E.A.. The Rosetta Stone. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1989 (paperback, ISBN 0486261638); Chicago Ridge, IL: Ares Publishers, 1995 (paperback, ISBN 0890053316).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.