Hood, Robin

m (Robot: Remove contracted tag) |

|||

| (118 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}}{{epname|Hood, Robin}} | ||

| + | [[Image:Robin Hood Memorial.jpg|thumb|300px|Robin Hood memorial statue in [[Nottingham]].]] | ||

| + | '''Robin Hood''' is an [[archetype|archetypal]] figure in [[England|English]] [[folklore]], whose story originates from [[medieval]] times but who remains significant in popular culture, where he is known for robbing the rich to give to the poor and fighting against injustice and tyranny. His band consists of a "seven [[twenty|score]]" group of fellow outlawed [[yeomen]] – called his "[[Merry Men]]."<ref>"Merry man" has referred to a follower of a knight or outlaw since the late fourteenth century, [https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=merry%20man Merry man] ''Online Etymology Dictionary''. Retrieved March 2, 2023.</ref> He has been the subject of numerous movies, television series, books, comics, and plays. There is no consensus as to whether or not Robin Hood is based on a historical figure. In popular culture Robin Hood and his band are usually seen as living in [[Sherwood Forest]] in [[Nottinghamshire]]. Although much of the action of the early [[ballad]]s does take place in Nottinghamshire, these ballads show Robin Hood based in the [[Barnsdale]] area of what is now [[South Yorkshire]] (which borders Nottinghamshire), and other traditions also point to [[Yorkshire]].<ref>[https://www.bbc.co.uk/nottingham/features/2004/01/robin_hood_county.shtml Robin Hood - On the move?] ''BBC'', January 2004. Retrieved March 2, 2023.</ref><ref>Barbara Green, [https://www.bbc.co.uk/bradford/sense_of_place/robin_hood.shtml Dead in West Yorkshire? Robin Hood] ''BBC'', February 2003. Retrieved March 2, 2023.</ref> | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The first clear reference to "rhymes of Robin Hood" is from the fourteenth century poem [[Piers Plowman]], but the earliest surviving copies of the narrative ballads which tell his story have been dated to the fifteenth century. In these early accounts Robin Hood's partisanship of the lower classes, his [[Marianism]] and associated special regard for women, his anti-clericalism and his particular animus towards the [[Sheriff of Nottingham]] are already clear.<ref>[https://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/child/ch117.htm ''A Gest of Robin Hood'' stanzas 10-15] ''Sacred Texts''. Retrieved March 2, 2023.</ref> In the oldest surviving accounts a particular reason for the outlaw's hostility to the sheriff is not given<ref name=Holt>J. C. Holt, ''Robin Hood'' (Thames & Hudson, 1989, ISBN 0500275416).</ref> but in later versions the sheriff is despotic and gravely abuses his position, appropriating land, levying excessive taxation, and persecuting the poor. In some later tales the antagonist is Prince John, based on the historical [[John of England]] (1166 – 1216), who is seen as the unjust usurper of his [[pious]] brother [[Richard I of England|Richard the Lionheart]]. In the oldest versions surviving, Robin Hood is a [[yeoman]], but in some later versions he is described as a [[nobleman]], [[Earl of Huntingdon]] or [[Lord of the Manor]] of [[Loxley, South Yorkshire|Loxley]] (or Locksley), usually designated Robin of Loxley, who was unjustly deprived of his lands.<ref name=Holt/> | ||

| − | + | ==Early References== | |

| − | + | The early ballads link Robin Hood to identifiable real places and many are convinced that he was a real person, more or less accurately portrayed. A number of theories as to the identity of "the real Robin Hood" have their supporters. Some of these theories posit that "Robin Hood" or "Robert Hood" or the like was his actual name; others suggest that this may have been merely a nick-name disguising a medieval bandit perhaps known to history under another name.<ref>Brian Benison, ''Robin Hood-The Real Story'' (Leslie Brian Benison, 2004, ISBN 978-0954847302). </ref> It is not inherently impossible that the early Robin Hood ballads were essentially works of fiction, one could compare the ballad of the outlawed archer [[Adam Bell]] of [[Inglewood Forest]], and it has been argued that the tales of Robin Hood have some similarities to the tales told of such historical outlaws such as [[Hereward the Wake]] (c. 1035 — 1072), [[Eustace the Monk]] (b. 1170), and [[Fulk FitzWarin]] - the latter of whom was a [[Normans|Norman]] noble who was disinherited and became an [[outlaw]] and an enemy of [[John of England]].<ref>Bob Curran, ''Walking with the Green Man: Father of the Forest, Spirit of Nature'' (New Page Books, 2007, ISBN 978-1564149312).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The oldest references to Robin Hood are not historical records, or even ballads recounting his exploits, but hints and allusions found in various works. From 1228 onwards the names 'Robinhood,' 'Robehod,' or 'Hobbehod' occur in the rolls of several English Justices. The majority of these references date from the late thirteenth century. Between 1261 and 1300 there are at least eight references to 'Rabunhod' in various regions across England, from [[Berkshire]] in the south to [[York]] in the north.<ref name=Holt/> | |

| − | + | The term seems to be applied as a form of shorthand to any fugitive or outlaw. Even at this early stage, the name Robin Hood is used as that of an [[archetype|archetypal]] criminal. This usage continues throughout the [[medieval period]]. The name was still used to describe sedition and treachery in 1605, when [[Guy Fawkes]] and his associates were branded "Robin Hoods" by [[Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury|Robert Cecil]]. | |

| + | |||

| + | The first allusion to a literary tradition of Robin Hood tales occurs in [[William Langland]]'s ''[[Piers Plowman]]'' (c.1362–c.1386) in which Sloth, the lazy priest, confesses: "''I kan'' [know] ''not parfitly'' [perfectly] ''my Paternoster as the preest it syngeth,/ But I kan rymes of Robyn Hood''."<ref> William Langland, [https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=cme;cc=cme;view=text;idno=PPlLan;rgn=div1;node=PPlLan:6 V.396] The vision of ''Piers Plowman''. Retrieved March 2, 2023.</ref> | ||

| − | + | The first mention of a quasi-historical Robin Hood is given in [[Andrew of Wyntoun]]'s ''Orygynale Chronicle,'' written about 1420. The following lines occur with little contextualization under the year 1283: | |

| − | |||

| − | + | :Lytil Jhon and Robyne Hude | |

| + | :Wayth-men ware commendyd gude | ||

| + | :In Yngil-wode and Barnysdale | ||

| + | :Thai oysyd all this tyme thare trawale. | ||

| − | The | + | The next notice is a statement in the ''[[Scotichronicon]],'' composed by [[John Fordun]] between 1377 and 1384, and revised by [[Walter Bower]] in about 1440. Among Bower's many interpolations is a passage which directly refers to Robin. It is inserted after Fordun's account of the defeat of [[Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester|Simon de Montfort]] and the punishment of his adherents. Robin is represented as a fighter for de Montford's cause.<ref name=Dobson>R. B. Dobson and J. Taylor (eds.), ''Rymes of Robin Hood'' (Sutton Publishing Ltd, 1997, ISBN 0750916613), 5.</ref>This was in fact true of the historical outlaw of [[Sherwood Forest]] [[Roger Godberd]], whose points of similarity to the Robin Hood of the ballads have often been noted <ref>Maurice Keen, ''The Outlaws of Medieval England'' (Routledge, 2000, ISBN 978-0415239004). </ref> |

| − | : | + | Bower writes: |

| − | + | <blockquote>Then [c.1266] arose the famous murderer, Robert Hood, as well as Little John, together with their accomplices from among the disinherited, whom the foolish populace are so inordinately fond of celebrating both in tragedies and comedies, and about whom they are delighted to hear the jesters and minstrels sing above all other ballads.<ref>Walter Bower, ''Scotichronicon'' (1440), in Stephen T. Knight and Thomas Ohlgren (eds.), ''Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales'' (Medieval Institute Publications, 2000, ISBN 978-1580440677).</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Despite Bower's reference to Robin as a 'murderer,' his account is followed by a brief tale in which Robin becomes a symbol of piety, gaining a decisive victory after hearing the [[Mass (liturgy)|Mass]]. | |

| − | + | There is an inscription on a grave in the grounds of [[Kirklees, Kirklees|Kirklees Priory]] near [[Kirklees Hall]] which claims to be the tomb of Robin Hood: | |

| − | + | ::Hear undernead dis laitl stean | |

| + | ::Lais Robert Earl of Huntingun | ||

| + | ::Near arcir der as hie sa geud | ||

| + | ::An pipl kauld im Robin Heud | ||

| + | ::Sic utlaws as hi an is men | ||

| + | ::Vil England nivr si agen. | ||

| + | :::Obiit 24 Kal Dekembris 1247 | ||

| − | + | Despite appearances, there is little reason to give the stone any credence. It certainly cannot date from the thirteenth century; notwithstanding the implausibility of a thirteenth century funeral monument being composed in English, the language of the inscription is highly suspect. Its orthography does not correspond to the written forms of [[Middle English]] at all: there are no inflected '—e's, the plural accusative [[pronoun]] 'hi' is used as a singular nominative, and the singular present indicative [[verb]] 'lais' is formed without the Middle English '—th' ending. Overall, the epitaph more closely resembles modern [[English (language)|English]] written in a deliberately 'archaic' style. Furthermore, the reference to Huntingdon is [[anachronistic]]: the first recorded mention of the title in the context of Robin Hood occurs in the 1598 play ''The Downfall of Robert, Earl of Huntington'' by [[Anthony Munday]]. The monument can only be a seventeenth century [[forgery]]. | |

| − | + | Therefore this Robin Hood is largely fictional by this time. The medieval texts do not refer to him directly, but mediate their allusions through a body of accounts and reports: for Langland Robin exists principally in "rimes," for Bower "comedies and tragedies," while for Wyntoun he is "commendyd gude." Even in a legal context, where one would expect to find verifiable references, he is primarily a [[symbol]], a generalized outlaw-figure rather than an individual. Consequently, in the medieval period itself, Robin Hood already belongs more to literature than to history. In fact, in an anonymous carol of c.1450, he is treated in precisely this manner—as a joke, a figure that the audience will instantly recognize as imaginary: "He that made this songe full good,/ Came of the northe and the sothern blode,/ And somewhat kyne to Robert Hoad."<ref>Thomas Wright, ''Songs and Carols'' (Legare Street Press, 2022 (original 1847), ISBN 1019035080).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | : | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Sources== | |

| + | [[File:Robin shoots with sir Guy by Louis Rhead 1912.png|thumb|300px|"Robin shoots with Sir Guy" by Louis Rhead.]] | ||

| + | The tales of Robin do not appear to have stemmed from [[mythology]] or [[folklore]]. While there are occasional efforts to trace the figure to fairies (such as [[Puck (mythology)|Puck]] under the alias [[Robin Goodfellow]]) or other mythological origins, good evidence for this has not been found, and when Robin Hood has been connected to such folklore, it is a later development. While Robin Hood and his men often show improbable skill in archery, swordplay, and disguise, they are no more exaggerated than those characters in other ballads, such as ''[[Kinmont Willie]]'', which were based on historical events. The origin of the legend is claimed by some to have stemmed from actual outlaws, or from tales of outlaws, such as [[Hereward the Wake]], [[Eustace the Monk]], and [[Fulk FitzWarin]].<ref name=Holt/> | ||

| − | + | There are many Robin Hood tales, "The prince of thieves" is one of his many, featuring both historical and fictitious outlaws. Hereward appears in a ballad much like ''Robin Hood and the Potter,'' and as the Hereward ballad is older, it appears to be the source. The ballad ''Adam Bell, Clym of the Cloughe and Wyllyam of Cloudeslee'' runs parallel to ''Robin Hood and the Monk,'' but it is not clear whether either one is the source for the other, or whether they merely show that such tales were told of outlaws. Some early Robin Hood stories appear to be unique, such as the story where Robin gives a [[knight]], generally called [[Richard at the Lee]], money to pay off his mortgage to an abbot, but this may merely indicate that no parallels have survived.<ref name=Holt/> | |

| − | ==Ballads and | + | ==Ballads and Tales== |

| − | The earliest surviving Robin Hood text is | + | ===Earlier versions=== |

| + | The earliest surviving Robin Hood text is "Robin Hood and the Monk." This is preserved in Cambridge University manuscript Ff.5.48, which was written shortly after 1450. It contains many of the elements still associated with the legend, from the Nottingham setting to the bitter enmity between Robin and the local sheriff.<ref name=Knight>Stephen T. Knight and Thomas Ohlgren (eds.), ''Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales'' (Medieval Institute Publications, 2000, ISBN 978-1580440677).</ref> | ||

| − | + | The first printed version is ''A Gest of Robyn Hode'' (c.1475), a collection of separate stories which attempts to unite the episodes into a single continuous [[narrative]].<ref>Thomas Ohlgren, ''Robin Hood: The Early Poems, 1465-1560'' (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2007, ISBN 978-1611493092). </ref> After this comes "Robin Hood and the Potter"<ref name=Knight/> contained in a manuscript of c.1503. "The Potter" is markedly different in tone from "The Monk": whereas the earlier tale is 'a thriller'<ref name=Holt/> the latter is more comic, its plot involving trickery and cunning rather than straightforward force. The difference between the two texts recalls Bower's claim that Robin-tales may be both 'comedies and tragedies.' Other early texts are dramatic pieces such as the fragmentary ''Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham''<ref name=Knight/> (c.1472). These are particularly noteworthy as they show Robin's integration into [[May Day]] rituals towards the end of the [[Middle Ages]]. | |

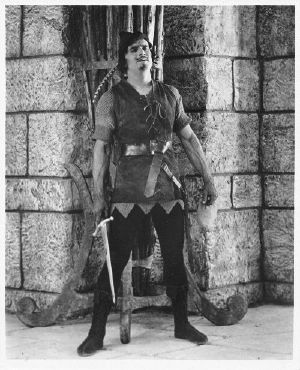

| + | [[Image:Fairbanks Robin Hood standing by wall w sword.jpg|300px|thumb|[[Douglas Fairbanks]] as Robin Hood; the sword with which he is depicted was common in the oldest ballads.]] | ||

| − | + | The plots of neither "the Monk" nor "the Potter" are included in the Gest; neither is the plot of [[Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne]] which is probably at least as early as those two ballads although preserved in a more recent copy. Each of these three [[ballad]]s survived in a single copy; this should serve as a warning that we do not know how much of the medieval legend has survived. | |

| − | + | The character of Robin in these first texts is rougher edged than in his later incarnations. In [[Robin Hood and the Monk]], for example, he is shown as quick tempered and violent, assaulting Little John for defeating him in an archery contest; in the same ballad [[Much the Miller's Son]] casually kills a "little page" in the course of rescuing Robin Hood from prison.<ref>[https://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/child/ch119.htm Robin Hood and the Monk] ''Sacred Texts''. Retrieved March 3, 2023. </ref> Nothing in any extant early ballad is stated about 'giving to the poor,' although in a "A Gest of Robyn Hode" Robin does make a large [[loan]] to an unfortunate [[knight]] which he does not in the end require to be repaid.<ref name=Holt/> But from the beginning Robin Hood is on the side of the poor; the Gest quotes Robin Hood as instructing his men that when they rob: "loke ye do no husbonde harme/That tilleth with his ploughe./No more ye shall no gode yeman/ | |

| + | That walketh by gren -wode shawe;/Ne no knyght ne no squyer/ That wol be a gode felawe." And the Gest sums up: "he was a good outlawe,/ And dyde pore men moch god." <ref>[https://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/child/ch117.htm The Gest of Robyn Hode] ''Sacred Texts''. Retrieved March 3, 2023.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Within Robin Hood's band medieval forms of [[courtesy]] rather than modern ideals of equality are generally in evidence. In the early ballads Robin's men usually kneel before him in strict obedience: in ''A Gest of Robyn Hode'' the king even observes that "His men are more at his byddynge/Then my men be at myn." Their social status, as yeomen, is shown by their weapons; they use [[sword]]s rather than [[quarterstaff]]s. The only character to use a quarterstaff in the early ballads is the potter, and Robin Hood does not take to a staff until the eighteenth century ''Robin Hood and Little John.''<ref name=Holt/> | |

| − | + | While he is sometimes described as a figure of peasant revolt, the details of his legends do not match this. He is not a peasant but an archer, and his tales make no mention of the complaints of the peasants, such as oppressive taxes. He appears not so much as a revolt against societal standards as an embodiment of them, being generous, pious, and courteous, opposed to stingy, worldly, and churlish foes. His tales glorified violence, but did so in a violent era.<ref name=Holt/> | |

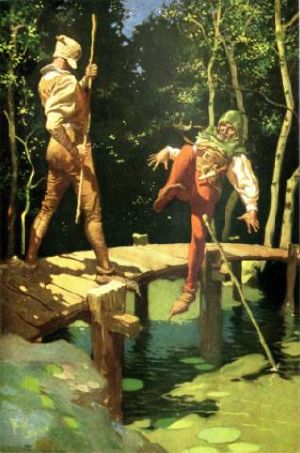

| + | [[Image:Little John and Robin Hood by Frank Godwin.jpg|300px|thumb|"Little John and Robin Hood" by [[Frank Godwin]].]] | ||

| + | Although the term "Merry Men" belongs to a later period, the ballads do name several of Robin's companions.<ref name=Richards>Jeffrey Richards, ''Swordsmen of the Screen: From Douglas Fairbanks to Michael York'' (Routledge, 2016, ISBN 978-1138996663).</ref> These include [[Will Scarlet|Will Scarlet (or Scathlock)]], [[Much the Miller's Son]], and [[Little John]]—who was called "little" as a joke, as he was quite the opposite. Even though the band is regularly described as being over a hundred men, usually only three or four are specified. Some appear only once or twice in a ballad: [[Will Stutly]] in ''[[Robin Hood Rescuing Will Stutly]]'' and ''Robin Hood and Little John''; [[David of Doncaster]] in ''[[Robin Hood and the Golden Arrow]]''; [[Gilbert Whitehand|Gilbert with the White Hand]] in ''[[A Gest of Robyn Hode]]''; and [[Arthur a Bland]] in ''Robin Hood and the Tanner.''<ref name=Beginners>Allen W. Wright, [https://www.boldoutlaw.com/robbeg/index.html A Beginner's Guide to Robin Hood] Retrieved March 2, 2023.</ref> Many later adapters developed these characters. [[Guy of Gisbourne]] also appeared in the legend at this point, as was another outlaw Richard the Divine who was hired by the sheriff to hunt Robin Hood, and who dies at Robin's hand.<ref name=Holt/> | ||

| − | + | ===First printed versions=== | |

| + | Printed versions of the Robin Hood ballads, generally based on the ''Gest,'' appear in the early sixteenth century, shortly after the introduction of [[printing]] in [[England]]. Later that century Robin is promoted to the level of [[aristocracy|nobleman]]: he is styled Earl of Huntington, Robert of Locksley, or [[Robert Fitz Ooth]]. In the early ballads, by contrast, he was a member of the [[yeoman]] classes, a common freeholder possessing a small landed estate.<ref name=Holt/> | ||

| − | + | In the fifteenth century, Robin Hood became associated with [[May Day]] celebrations; people would dress as Robin or as other members of his band for the festivities. This was not practiced throughout England, but in regions where it was practiced, lasted until Elizabethan times, and during the reign of [[Henry VIII]], was briefly popular at court.<ref>Ronald Hutton, ''The Stations of the Sun'' (Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0192854483).</ref> This often put the figure in the role of a May King, presiding over games and processions, but [[Play (theatre)|play]]s were also performed with the characters in the roles. These plays could be enacted at "church ales," a means by which churches raised funds.<ref>Ronald Hutton, ''The Rise and Fall of Merry England: The Ritual Year 1400-1700'' (Oxford University Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0198203636).</ref> A complaint of 1492, brought to the Star Chamber, accuses men of acting riotously by coming to a fair as Robin Hood and his men; the accused defended themselves on the grounds that the practice was a long-standing custom to raise money for churches, and they had not acted riotously but peaceably.<ref name=Holt/> | |

| − | + | [[Image:Robin Hood and Maid Marian.JPG|300px|thumb|Robin Hood and Maid Marian]] | |

| + | It is from this association that Robin's romantic attachment to [[Maid Marian]] (or Marion) stems. The naming of Marian may have come from the [[France|French]] pastoral play of c. 1280, the ''Jeu de Robin et Marion,'' although this play is unrelated to the English legends. Both Robin and Marian were certainly associated with [[May Day]] festivities in England (as was Friar Tuck), but these were originally two distinct types of performance—[[Alexander Barclay]], writing in c.1500, refers to "some merry fytte of Maid Marian '''or else''' of Robin Hood"—but the characters were brought together.<ref name=Richards/> Marian did not immediately gain the unquestioned role; in ''Robin Hood's Birth, Breeding, Valor and Marriage,'' his sweetheart is 'Clorinda the Queen of the Shepherdesses'.<ref name=Holt/> Clorinda survives in some later stories as an alias of Marian.<ref name=Beginners/> | ||

| − | The | + | The first allusions to Robin Hood as stealing from the rich and giving to the poor appear in the 16th century. However, they still play a minor role in the legend; Robin still is prone to waylaying poor men, such as [[Robin Hood and the Tinker|tinkers]] and [[Robin Hood and the Beggar, II|beggars]].<ref name=Holt/> |

| − | + | In the sixteenth century, Robin Hood is given a specific historical setting. Up until this point there was little interest in exactly when Robin's adventures took place. The original ballads refer at various points to 'King Edward', without stipulating whether this is [[Edward I of England|Edward I]], [[Edward II of England|Edward II]], or [[Edward III of England|Edward III]]. Hood may thus have been active at any point between 1272 and 1377. However, during the sixteenth century the stories become fixed to the 1190s, the period in which [[Richard I of England|King Richard]] was absent from his throne, fighting in the [[Third Crusade|crusade]]s.<ref name=Holt/> This date is first proposed by [[John Mair]] in his ''Historia Majoris Britanniæ'' (1521), and gains popular acceptance by the end of the century. | |

| − | + | Giving Robin an aristocratic title and female love interest, and placing him in the historical context of the true king's absence, all represent moves to domesticate his legend and reconcile it to ruling powers. In this, his legend is similar to that of [[King Arthur]], which morphed from a dangerous male-centered story to a more comfortable, chivalrous romance under the troubadours serving [[Eleanor of Aquitaine]]. From the 16th century on, the legend of Robin Hood is often used to promote the hereditary [[ruling class]], [[Romantic love|romance]], and religious [[piety]]. The "criminal" element is retained to provide dramatic color, rather than as a real challenge to convention. | |

| − | + | In 1601 the story appears in a rare historical [[drama|play]] chronicling the late twelfth century: "The Downfall of Robert, Earl of Huntingdon, afterwards called Robin Hood of merrie Sherwoode; with his love to chaste Matilda, the Lord Fitz-Walter's daughter, afterwards his fair Maid Marian."<ref>Anthony Munday, ''The Downfall of Robert Earl of Huntingdon'' (Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007 (original 1601), ISBN 978-0548750407).</ref> The seventeenth century introduced the minstrel [[Alan-a-Dale]]. He first appeared in a seventeenth century [[Ballads#Broadsheet ballads|broadside ballad]], and unlike many of the characters thus associated, managed to adhere to the legend.<ref name=Holt/> | |

| − | In | ||

| − | :'' | + | In 1795, [[Joseph Ritson]] published an enormously influential edition of the Robin Hood ballads.<ref>Joseph Ritson, ''Robin Hood: A Collection of All the Ancient Poems, Songs, and Ballads, Now Extant, Relative to That Celebrated English Outlaw: to Which Are Prefixed Historical Anecdotes of His Life'' (Wentworth Press, 2016 (original 1795), ISBN 978-1363290710).</ref> This collection provided English poets and novelists with a convenient source book, giving them "the opportunity to recreate Robin Hood in their own imagination."<ref name=Dobson/> Ritson's interpretation of Robin Hood was also influential, including the modern concept of stealing from the rich and giving to the poor. It has been noted, however, that Ritson "began as a Jacobite and ended as a Jacobin," and "certainly reconstructed him [Robin] in the image of a radical."<ref name=Holt/> |

| − | In [[ | + | ===Later versions=== |

| + | In the eighteenth century, the stories become even more conservative, and develop a slightly more [[farce|farcical]] vein. From this period there are a number of ballads in which Robin is severely "drubbed" by a succession of professionals including [[Robin Hood and the Tanner|a tanner]], [[Robin Hood and the Tinker|a tinker]] and [[Robin Hood and the Ranger|a ranger]].<ref name=Holt/> In fact, the only character who does not get the better of Hood is the luckless Sheriff. Yet even in these ballads Robin is more than a mere simpleton: on the contrary, he often acts with great shrewdness. The tinker, setting out to capture Robin, only manages to fight with him after he has been cheated out of his money and the [[arrest warrant]] he is carrying. In ''Robin Hood's Golden Prize,'' Robin disguises himself as a [[friar]] and cheats two priests out of their cash. Even when Robin is defeated, he usually tricks his foe into letting him sound his horn, summoning the Merry Men to his aid. [[Robin Hood's Delight|When]] his enemies do not fall for this ruse, he persuades them to drink with him instead. | ||

| − | + | The continued popularity of the Robin Hood tales is attested by a number of literary references. In [[William Shakespeare]]'s [[comedy]] ''As You Like It,'' the exiled duke and his men "live like the old Robin Hood of England," while [[Ben Jonson]] produced the (incomplete) [[masque]] ''The Sad Shepherd, or a Tale of Robin Hood''<ref> Ben Jonson, [https://d.lib.rochester.edu/robin-hood/text/jonson-sad-shepherd The Sad Shepherd: or, A Tale of Robin Hood] ''University of Rochester''. Retrieved March 3, 2023.</ref> as a satire on [[Puritanism]]. Somewhat later, the [[Romantic poetry|Romantic]] poet [[John Keats]] composed ''Robin Hood. To A Friend''<ref> John Keats, [https://d.lib.rochester.edu/robin-hood/text/keats-robin-hood Robin Hood: To a Friend]. ''University of Rochester''. Retrieved March 3, 2023.</ref> and [[Alfred Lord Tennyson]] wrote a play ''The Foresters, or Robin Hood and Maid Marian,''<ref> Alfred Lord Tennyson, [https://d.lib.rochester.edu/robin-hood/text/tennyson-foresters The Foresters: Robin Hood and Maid Marian]. ''University of Rochester''. Retrieved March 3, 2023.</ref> which was presented with incidental music by Sir [[Arthur Sullivan]] in 1892. Later still, [[T. H. White]] featured Robin and his band in ''[[The Sword in the Stone]]''—[[anachronism|anachronistically]], since the [[novel]]'s chief theme is the childhood of [[King Arthur]].<ref>W.R. Irwin ''The Game of the Impossible'' (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1976, ISBN 978-0252005879).</ref> | |

| − | + | [[Image:The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, 1 Title page.png|thumb|300px|The title page of [[Howard Pyle]]'s 1883 novel, ''The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood.'']] | |

| − | [[ | + | The [[Victorian era]] generated its own distinct versions of Robin Hood. The traditional tales were often adapted for children, most notably in [[Howard Pyle]]'s ''Merry Adventures of Robin Hood.''<ref> Howard Pyle, ''The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood'' (SeaWolf Press, 2018 (original 1883), ISBN 978-1949460520).</ref> These versions firmly stamp Robin as a staunch philanthropist, a man who takes from the rich to give to the poor. Nevertheless, the adventures are still more local than national in scope: while [[Richard I of England|Richard]]'s participation in [[Third Crusade|the Crusades]] is mentioned in passing, Robin takes no stand against [[John of England|Prince John]], and plays no part in raising the ransom to free Richard. These developments are part of the twentieth century Robin Hood myth. The idea of Robin Hood as a high-minded [[Saxon people|Saxon]] fighting [[Normans|Norman]] Lords also originates in the 19th century. The most notable contributions to this idea of Robin are [[Jacques Nicolas Augustin Thierry|Thierry's]] ''{{lang|fr|Histoire de la [[Norman Conquest|Conquête de l'Angleterre par les Normands]]}}'' (1825), and [[Scott, Walter|Sir Walter Scott]]'s ''[[Ivanhoe]]'' (1819). In this last work in particular, the modern Robin Hood—"King of Outlaws and prince of good fellows!" as Richard the Lionheart calls him—makes his début.<ref name="Wolfshead Ages">Allen W. Wright, [https://www.boldoutlaw.com/robages/robages7.html Wolfshead through the Ages]. Retrieved March 2, 2023.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | + | The twentieth century has grafted still further details on to the original legends. The movie ''[[The Adventures of Robin Hood (film)|The Adventures of Robin Hood]]'' portrayed Robin as a hero on a national scale, leading the oppressed Saxons in revolt against their Norman overlords while Richard the Lion-Hearted fought in the Crusades; this movie established itself so definitively that many studios resorted to movies about his son (invented for that purpose) rather than compete with the image of this one.<ref name="Wolfshead Ages"/> | |

| − | + | Since the 1980s, it has become commonplace to include a [[Saracen]] among the Merry Men, a trend which began with the character [[Nasir (Robin of Sherwood)|Nasir]] in the ''Robin of Sherwood'' television series. Later versions of the story have followed suit: the 1991 movie ''Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves'' and 2006 [[BBC]] TV series ''[[Robin Hood (BBC TV series)|Robin Hood]]'' each contain equivalents of Nasir, in the figures of Azeem and [[Djaq]] respectively.<ref name="Wolfshead Ages"/> | |

| − | The | + | The Robin Hood legend has thus been subject to numerous shifts and mutations throughout its history. Robin himself has evolved from a yeoman bandit to a national hero of epic proportions, who not only supports the poor by taking from the rich, but heroically defends the [[Richard I of England|throne of England]] itself from unworthy and venal claimants. |

| − | + | ==List of traditional ballads== | |

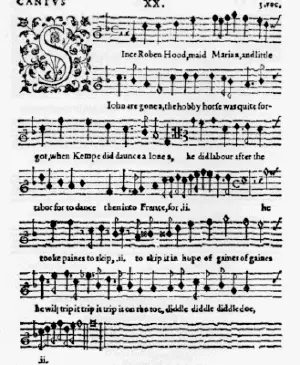

| + | [[Image:Since Robin Hood by Weelkes.png|300px|thumb|Elizabethan song of Robin Hood.]] | ||

| − | + | Ballads are the oldest existing form of the Robin Hood legends, although none of them are recorded at the time of the first allusions to him, and many are much later. They evince many common features, often opening with praise of the greenwood and relying heavily on disguise as a [[plot device]], but include a wide variation in tone and plot.<ref name=Holt/> The ballads below are sorted into three groups, very roughly according to date of first known free-standing copy. Ballads whose first recorded version appears (usually incomplete) in the [[Percy Folio]] may appear in later versions and may be much older than the mid-seventeenth century when the Folio was compiled. Any ballad may be older than the oldest copy which happens to survive, or descended from a lost older ballad. For example, the plot of Robin Hood's Death, found in the ''Percy Folio,'' is summarized in the fifteenth century [[A Gest of Robin Hood]], and it also appears in an eighteenth century version.<ref name=Dobson/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Early ballads=== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

| − | |||

*[[A Gest of Robyn Hode]] | *[[A Gest of Robyn Hode]] | ||

*[[Robin Hood and the Monk]] | *[[Robin Hood and the Monk]] | ||

| + | *[[Robin Hood and the Potter]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===''Percy Folio''=== | ||

| + | *[[Little John a Begging]] | ||

*[[Robin Hood's Death]] | *[[Robin Hood's Death]] | ||

| − | *[[Robin Hood and | + | *[[Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne]] |

| + | *[[Robin Hood and Queen Katherine]] | ||

*[[Robin Hood and the Butcher]] | *[[Robin Hood and the Butcher]] | ||

*[[Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar]] | *[[Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar]] | ||

| + | *[[Robin Hood Rescuing Three Squires]] | ||

*[[The Jolly Pinder of Wakefield]] | *[[The Jolly Pinder of Wakefield]] | ||

| − | *[[Robin Hood and the | + | |

| − | *[[Robin Hood and the | + | ===Other ballads=== |

| + | *[[A True Tale of Robin Hood]] | ||

| + | *[[Robin Hood and the Bishop]] | ||

| + | *[[Robin Hood and the Bishop of Hereford]] | ||

| + | *[[Robin Hood and the Golden Arrow]] | ||

*[[Robin Hood and the Newly Revived]] | *[[Robin Hood and the Newly Revived]] | ||

| − | |||

*[[Robin Hood and the Prince of Aragon]] | *[[Robin Hood and the Prince of Aragon]] | ||

| + | *[[Robin Hood and the Ranger]] | ||

*[[Robin Hood and the Scotchman]] | *[[Robin Hood and the Scotchman]] | ||

| − | *[[Robin Hood and the | + | *[[Robin Hood and the Tanner]] |

| − | *[[Robin Hood | + | *[[Robin Hood and the Tinker]] |

| − | *[[Robin Hood | + | *[[Robin Hood and the Valiant Knight]] |

| − | |||

*[[Robin Hood Rescuing Will Stutly]] | *[[Robin Hood Rescuing Will Stutly]] | ||

| − | *[[Robin Hood and | + | *[[Robin Hood's Birth, Breeding, Valor and Marriage]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

*[[Robin Hood's Chase]] | *[[Robin Hood's Chase]] | ||

| + | *[[Robin Hood's Delight]] | ||

*[[Robin Hood's Golden Prize]] | *[[Robin Hood's Golden Prize]] | ||

| + | *[[Robin Hood's Progress to Nottingham]] | ||

| + | *[[The Bold Pedlar and Robin Hood]] | ||

| + | *[[The King's Disguise, and Friendship with Robin Hood]] | ||

*[[The Noble Fisherman]] | *[[The Noble Fisherman]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Some ballads, such as ''Erlinton,'' feature Robin Hood in some variants, where the folk hero appears to be added to a ballad pre-existing him and in which he does not fit very well.<ref>Francis James Child, ''The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Volume 1'' (Andesite Press, 2017, ISBN 978-1375403146).</ref> He was added to one variant of ''Rose Red and the White Lily,'' apparently on no more connection than that one hero of the other variants is named "Brown Robin."<ref name=Child2>Francis James Child, ''The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Volume 2'' (Dover Publications, 2003, ISBN 0486431460).</ref> [[Francis James Child]] indeed retitled [[Child ballad]] 102; though it was titled ''The Birth of Robin Hood,'' its clear lack of connection with the Robin Hood cycle (and connection with other, unrelated ballads) led him to title it ''Willie and Earl Richard's Daughter'' in his collection.<ref name=Child2/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Robin Hood (adaption)== |

| − | + | ===Musical=== | |

| − | + | *''Robin Hood - Ein Abenteuer mit Musik'' (1995) - Festspiele Balver Höhle | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| − | + | {{reflist|2}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | + | *Benison, Brian. ''Robin Hood-The Real Story''. Leslie Brian Benison, 2004. ISBN 978-0954847302 | |

| − | + | *Child, Francis James. ''The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Volume 1''. Andesite Press, 2017. ISBN 978-1375403146 | |

| + | *Child, Francis James. ''The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Volume 2''. Dover Publications, 2003. ISBN 0486431460 | ||

| + | *Curran, Bob. ''Walking with the Green Man: Father of the Forest, Spirit of Nature.'' New Page Books, 2007. ISBN 978-1564149312 | ||

| + | *Dobson, John, and R.B. Taylor (eds.). ''Rymes of Robyn Hood: An Introduction to the English Outlaw.'' Sutton Publishing Ltd, 1997. ISBN 0750916613 | ||

| + | *Holt, J. C. ''Robin Hood.'' Thames & Hudson, 1989. ISBN 0500275416 | ||

| + | *Hutton, Ronald. ''The Rise and Fall of Merry England: The Ritual Year 1400-1700''. Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0198203636 | ||

| + | *Hutton, Ronald. ''The Stations of the Sun''. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0192854483 | ||

| + | *Irwin, W.R. ''The Game of the Impossible.'' Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0252005879 | ||

| + | *Keen, Maurice. ''The Outlaws of Medieval England''. Routledge, 2000. ISBN 978-0415239004 | ||

| + | *Knight, Stephen T., and Thomas Ohlgren. ''Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales''. Medieval Institute Publications, 2000. ISBN 978-1580440677 | ||

| + | *Munday, Anthony. ''The Downfall of Robert Earl of Huntingdon''. Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007 (original 1601). ISBN 978-0548750407 | ||

| + | *Ohlgren, Thomas. ''Robin Hood: The Early Poems, 1465-1560''. (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1611493092 | ||

| + | *Pyle, Howard. ''The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood''. SeaWolf Press, 2018 (original 1883). ISBN 978-1949460520 | ||

| + | *Richards, Jeffrey. ''Swordsmen of the Screen: From Douglas Fairbanks to Michael York.'' Routledge, 2016. ISBN 978-1138996663 | ||

| + | *Ritson, Joseph. ''Robin Hood: A Collection of All the Ancient Poems, Songs, and Ballads, Now Extant, Relative to That Celebrated English Outlaw: to Which Are Prefixed Historical Anecdotes of His Life''. Wentworth Press, 2016 (original 1795). ISBN 978-1363290710 | ||

| + | *Wright, Thomas. ''Songs and Carols.'' Legare Street Press, 2022 (original 1847). ISBN 1019035080 | ||

| − | + | ==External links== | |

| − | + | All links retrieved March 2, 2023. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ''[[The | + | *[https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/middle_ages/robin_01.shtml Robin Hood and his Historical Context] ''BBC'' |

| + | * [https://www.boldoutlaw.com/ Robin Hood: Bold Outlaw of Barnsdale and Sherwood] | ||

| + | * [https://d.lib.rochester.edu/robin-hood The Robin Hood Project] '' University of Rochester'' | ||

| + | * [https://www.boldoutlaw.com/robbeg/index.html A Beginner's Guide to Robin Hood] by Allen W. Wright | ||

| + | * [https://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/publication/knight-and-ohlgren-robin-hood-and-other-outlaw-tales ''Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales''] edited by Stephen Knight and Thomas H. Ohlgren. ''University of Rochester''. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{Robin Hood}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | [[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | ||

| − | {{credit| | + | [[Category:Literature]] |

| + | [[category:History]] | ||

| + | {{credit|Robin_Hood|212772008}} | ||

Latest revision as of 17:08, 16 August 2023

Robin Hood is an archetypal figure in English folklore, whose story originates from medieval times but who remains significant in popular culture, where he is known for robbing the rich to give to the poor and fighting against injustice and tyranny. His band consists of a "seven score" group of fellow outlawed yeomen – called his "Merry Men."[1] He has been the subject of numerous movies, television series, books, comics, and plays. There is no consensus as to whether or not Robin Hood is based on a historical figure. In popular culture Robin Hood and his band are usually seen as living in Sherwood Forest in Nottinghamshire. Although much of the action of the early ballads does take place in Nottinghamshire, these ballads show Robin Hood based in the Barnsdale area of what is now South Yorkshire (which borders Nottinghamshire), and other traditions also point to Yorkshire.[2][3]

The first clear reference to "rhymes of Robin Hood" is from the fourteenth century poem Piers Plowman, but the earliest surviving copies of the narrative ballads which tell his story have been dated to the fifteenth century. In these early accounts Robin Hood's partisanship of the lower classes, his Marianism and associated special regard for women, his anti-clericalism and his particular animus towards the Sheriff of Nottingham are already clear.[4] In the oldest surviving accounts a particular reason for the outlaw's hostility to the sheriff is not given[5] but in later versions the sheriff is despotic and gravely abuses his position, appropriating land, levying excessive taxation, and persecuting the poor. In some later tales the antagonist is Prince John, based on the historical John of England (1166 – 1216), who is seen as the unjust usurper of his pious brother Richard the Lionheart. In the oldest versions surviving, Robin Hood is a yeoman, but in some later versions he is described as a nobleman, Earl of Huntingdon or Lord of the Manor of Loxley (or Locksley), usually designated Robin of Loxley, who was unjustly deprived of his lands.[5]

Early References

The early ballads link Robin Hood to identifiable real places and many are convinced that he was a real person, more or less accurately portrayed. A number of theories as to the identity of "the real Robin Hood" have their supporters. Some of these theories posit that "Robin Hood" or "Robert Hood" or the like was his actual name; others suggest that this may have been merely a nick-name disguising a medieval bandit perhaps known to history under another name.[6] It is not inherently impossible that the early Robin Hood ballads were essentially works of fiction, one could compare the ballad of the outlawed archer Adam Bell of Inglewood Forest, and it has been argued that the tales of Robin Hood have some similarities to the tales told of such historical outlaws such as Hereward the Wake (c. 1035 — 1072), Eustace the Monk (b. 1170), and Fulk FitzWarin - the latter of whom was a Norman noble who was disinherited and became an outlaw and an enemy of John of England.[7]

The oldest references to Robin Hood are not historical records, or even ballads recounting his exploits, but hints and allusions found in various works. From 1228 onwards the names 'Robinhood,' 'Robehod,' or 'Hobbehod' occur in the rolls of several English Justices. The majority of these references date from the late thirteenth century. Between 1261 and 1300 there are at least eight references to 'Rabunhod' in various regions across England, from Berkshire in the south to York in the north.[5]

The term seems to be applied as a form of shorthand to any fugitive or outlaw. Even at this early stage, the name Robin Hood is used as that of an archetypal criminal. This usage continues throughout the medieval period. The name was still used to describe sedition and treachery in 1605, when Guy Fawkes and his associates were branded "Robin Hoods" by Robert Cecil.

The first allusion to a literary tradition of Robin Hood tales occurs in William Langland's Piers Plowman (c.1362–c.1386) in which Sloth, the lazy priest, confesses: "I kan [know] not parfitly [perfectly] my Paternoster as the preest it syngeth,/ But I kan rymes of Robyn Hood."[8]

The first mention of a quasi-historical Robin Hood is given in Andrew of Wyntoun's Orygynale Chronicle, written about 1420. The following lines occur with little contextualization under the year 1283:

- Lytil Jhon and Robyne Hude

- Wayth-men ware commendyd gude

- In Yngil-wode and Barnysdale

- Thai oysyd all this tyme thare trawale.

The next notice is a statement in the Scotichronicon, composed by John Fordun between 1377 and 1384, and revised by Walter Bower in about 1440. Among Bower's many interpolations is a passage which directly refers to Robin. It is inserted after Fordun's account of the defeat of Simon de Montfort and the punishment of his adherents. Robin is represented as a fighter for de Montford's cause.[9]This was in fact true of the historical outlaw of Sherwood Forest Roger Godberd, whose points of similarity to the Robin Hood of the ballads have often been noted [10]

Bower writes:

Then [c.1266] arose the famous murderer, Robert Hood, as well as Little John, together with their accomplices from among the disinherited, whom the foolish populace are so inordinately fond of celebrating both in tragedies and comedies, and about whom they are delighted to hear the jesters and minstrels sing above all other ballads.[11]

Despite Bower's reference to Robin as a 'murderer,' his account is followed by a brief tale in which Robin becomes a symbol of piety, gaining a decisive victory after hearing the Mass.

There is an inscription on a grave in the grounds of Kirklees Priory near Kirklees Hall which claims to be the tomb of Robin Hood:

- Hear undernead dis laitl stean

- Lais Robert Earl of Huntingun

- Near arcir der as hie sa geud

- An pipl kauld im Robin Heud

- Sic utlaws as hi an is men

- Vil England nivr si agen.

- Obiit 24 Kal Dekembris 1247

Despite appearances, there is little reason to give the stone any credence. It certainly cannot date from the thirteenth century; notwithstanding the implausibility of a thirteenth century funeral monument being composed in English, the language of the inscription is highly suspect. Its orthography does not correspond to the written forms of Middle English at all: there are no inflected '—e's, the plural accusative pronoun 'hi' is used as a singular nominative, and the singular present indicative verb 'lais' is formed without the Middle English '—th' ending. Overall, the epitaph more closely resembles modern English written in a deliberately 'archaic' style. Furthermore, the reference to Huntingdon is anachronistic: the first recorded mention of the title in the context of Robin Hood occurs in the 1598 play The Downfall of Robert, Earl of Huntington by Anthony Munday. The monument can only be a seventeenth century forgery.

Therefore this Robin Hood is largely fictional by this time. The medieval texts do not refer to him directly, but mediate their allusions through a body of accounts and reports: for Langland Robin exists principally in "rimes," for Bower "comedies and tragedies," while for Wyntoun he is "commendyd gude." Even in a legal context, where one would expect to find verifiable references, he is primarily a symbol, a generalized outlaw-figure rather than an individual. Consequently, in the medieval period itself, Robin Hood already belongs more to literature than to history. In fact, in an anonymous carol of c.1450, he is treated in precisely this manner—as a joke, a figure that the audience will instantly recognize as imaginary: "He that made this songe full good,/ Came of the northe and the sothern blode,/ And somewhat kyne to Robert Hoad."[12]

Sources

The tales of Robin do not appear to have stemmed from mythology or folklore. While there are occasional efforts to trace the figure to fairies (such as Puck under the alias Robin Goodfellow) or other mythological origins, good evidence for this has not been found, and when Robin Hood has been connected to such folklore, it is a later development. While Robin Hood and his men often show improbable skill in archery, swordplay, and disguise, they are no more exaggerated than those characters in other ballads, such as Kinmont Willie, which were based on historical events. The origin of the legend is claimed by some to have stemmed from actual outlaws, or from tales of outlaws, such as Hereward the Wake, Eustace the Monk, and Fulk FitzWarin.[5]

There are many Robin Hood tales, "The prince of thieves" is one of his many, featuring both historical and fictitious outlaws. Hereward appears in a ballad much like Robin Hood and the Potter, and as the Hereward ballad is older, it appears to be the source. The ballad Adam Bell, Clym of the Cloughe and Wyllyam of Cloudeslee runs parallel to Robin Hood and the Monk, but it is not clear whether either one is the source for the other, or whether they merely show that such tales were told of outlaws. Some early Robin Hood stories appear to be unique, such as the story where Robin gives a knight, generally called Richard at the Lee, money to pay off his mortgage to an abbot, but this may merely indicate that no parallels have survived.[5]

Ballads and Tales

Earlier versions

The earliest surviving Robin Hood text is "Robin Hood and the Monk." This is preserved in Cambridge University manuscript Ff.5.48, which was written shortly after 1450. It contains many of the elements still associated with the legend, from the Nottingham setting to the bitter enmity between Robin and the local sheriff.[13]

The first printed version is A Gest of Robyn Hode (c.1475), a collection of separate stories which attempts to unite the episodes into a single continuous narrative.[14] After this comes "Robin Hood and the Potter"[13] contained in a manuscript of c.1503. "The Potter" is markedly different in tone from "The Monk": whereas the earlier tale is 'a thriller'[5] the latter is more comic, its plot involving trickery and cunning rather than straightforward force. The difference between the two texts recalls Bower's claim that Robin-tales may be both 'comedies and tragedies.' Other early texts are dramatic pieces such as the fragmentary Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham[13] (c.1472). These are particularly noteworthy as they show Robin's integration into May Day rituals towards the end of the Middle Ages.

The plots of neither "the Monk" nor "the Potter" are included in the Gest; neither is the plot of Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne which is probably at least as early as those two ballads although preserved in a more recent copy. Each of these three ballads survived in a single copy; this should serve as a warning that we do not know how much of the medieval legend has survived.

The character of Robin in these first texts is rougher edged than in his later incarnations. In Robin Hood and the Monk, for example, he is shown as quick tempered and violent, assaulting Little John for defeating him in an archery contest; in the same ballad Much the Miller's Son casually kills a "little page" in the course of rescuing Robin Hood from prison.[15] Nothing in any extant early ballad is stated about 'giving to the poor,' although in a "A Gest of Robyn Hode" Robin does make a large loan to an unfortunate knight which he does not in the end require to be repaid.[5] But from the beginning Robin Hood is on the side of the poor; the Gest quotes Robin Hood as instructing his men that when they rob: "loke ye do no husbonde harme/That tilleth with his ploughe./No more ye shall no gode yeman/ That walketh by gren -wode shawe;/Ne no knyght ne no squyer/ That wol be a gode felawe." And the Gest sums up: "he was a good outlawe,/ And dyde pore men moch god." [16]

Within Robin Hood's band medieval forms of courtesy rather than modern ideals of equality are generally in evidence. In the early ballads Robin's men usually kneel before him in strict obedience: in A Gest of Robyn Hode the king even observes that "His men are more at his byddynge/Then my men be at myn." Their social status, as yeomen, is shown by their weapons; they use swords rather than quarterstaffs. The only character to use a quarterstaff in the early ballads is the potter, and Robin Hood does not take to a staff until the eighteenth century Robin Hood and Little John.[5]

While he is sometimes described as a figure of peasant revolt, the details of his legends do not match this. He is not a peasant but an archer, and his tales make no mention of the complaints of the peasants, such as oppressive taxes. He appears not so much as a revolt against societal standards as an embodiment of them, being generous, pious, and courteous, opposed to stingy, worldly, and churlish foes. His tales glorified violence, but did so in a violent era.[5]

Although the term "Merry Men" belongs to a later period, the ballads do name several of Robin's companions.[17] These include Will Scarlet (or Scathlock), Much the Miller's Son, and Little John—who was called "little" as a joke, as he was quite the opposite. Even though the band is regularly described as being over a hundred men, usually only three or four are specified. Some appear only once or twice in a ballad: Will Stutly in Robin Hood Rescuing Will Stutly and Robin Hood and Little John; David of Doncaster in Robin Hood and the Golden Arrow; Gilbert with the White Hand in A Gest of Robyn Hode; and Arthur a Bland in Robin Hood and the Tanner.[18] Many later adapters developed these characters. Guy of Gisbourne also appeared in the legend at this point, as was another outlaw Richard the Divine who was hired by the sheriff to hunt Robin Hood, and who dies at Robin's hand.[5]

First printed versions

Printed versions of the Robin Hood ballads, generally based on the Gest, appear in the early sixteenth century, shortly after the introduction of printing in England. Later that century Robin is promoted to the level of nobleman: he is styled Earl of Huntington, Robert of Locksley, or Robert Fitz Ooth. In the early ballads, by contrast, he was a member of the yeoman classes, a common freeholder possessing a small landed estate.[5]

In the fifteenth century, Robin Hood became associated with May Day celebrations; people would dress as Robin or as other members of his band for the festivities. This was not practiced throughout England, but in regions where it was practiced, lasted until Elizabethan times, and during the reign of Henry VIII, was briefly popular at court.[19] This often put the figure in the role of a May King, presiding over games and processions, but plays were also performed with the characters in the roles. These plays could be enacted at "church ales," a means by which churches raised funds.[20] A complaint of 1492, brought to the Star Chamber, accuses men of acting riotously by coming to a fair as Robin Hood and his men; the accused defended themselves on the grounds that the practice was a long-standing custom to raise money for churches, and they had not acted riotously but peaceably.[5]

It is from this association that Robin's romantic attachment to Maid Marian (or Marion) stems. The naming of Marian may have come from the French pastoral play of c. 1280, the Jeu de Robin et Marion, although this play is unrelated to the English legends. Both Robin and Marian were certainly associated with May Day festivities in England (as was Friar Tuck), but these were originally two distinct types of performance—Alexander Barclay, writing in c.1500, refers to "some merry fytte of Maid Marian or else of Robin Hood"—but the characters were brought together.[17] Marian did not immediately gain the unquestioned role; in Robin Hood's Birth, Breeding, Valor and Marriage, his sweetheart is 'Clorinda the Queen of the Shepherdesses'.[5] Clorinda survives in some later stories as an alias of Marian.[18]

The first allusions to Robin Hood as stealing from the rich and giving to the poor appear in the 16th century. However, they still play a minor role in the legend; Robin still is prone to waylaying poor men, such as tinkers and beggars.[5]

In the sixteenth century, Robin Hood is given a specific historical setting. Up until this point there was little interest in exactly when Robin's adventures took place. The original ballads refer at various points to 'King Edward', without stipulating whether this is Edward I, Edward II, or Edward III. Hood may thus have been active at any point between 1272 and 1377. However, during the sixteenth century the stories become fixed to the 1190s, the period in which King Richard was absent from his throne, fighting in the crusades.[5] This date is first proposed by John Mair in his Historia Majoris Britanniæ (1521), and gains popular acceptance by the end of the century.

Giving Robin an aristocratic title and female love interest, and placing him in the historical context of the true king's absence, all represent moves to domesticate his legend and reconcile it to ruling powers. In this, his legend is similar to that of King Arthur, which morphed from a dangerous male-centered story to a more comfortable, chivalrous romance under the troubadours serving Eleanor of Aquitaine. From the 16th century on, the legend of Robin Hood is often used to promote the hereditary ruling class, romance, and religious piety. The "criminal" element is retained to provide dramatic color, rather than as a real challenge to convention.

In 1601 the story appears in a rare historical play chronicling the late twelfth century: "The Downfall of Robert, Earl of Huntingdon, afterwards called Robin Hood of merrie Sherwoode; with his love to chaste Matilda, the Lord Fitz-Walter's daughter, afterwards his fair Maid Marian."[21] The seventeenth century introduced the minstrel Alan-a-Dale. He first appeared in a seventeenth century broadside ballad, and unlike many of the characters thus associated, managed to adhere to the legend.[5]

In 1795, Joseph Ritson published an enormously influential edition of the Robin Hood ballads.[22] This collection provided English poets and novelists with a convenient source book, giving them "the opportunity to recreate Robin Hood in their own imagination."[9] Ritson's interpretation of Robin Hood was also influential, including the modern concept of stealing from the rich and giving to the poor. It has been noted, however, that Ritson "began as a Jacobite and ended as a Jacobin," and "certainly reconstructed him [Robin] in the image of a radical."[5]

Later versions

In the eighteenth century, the stories become even more conservative, and develop a slightly more farcical vein. From this period there are a number of ballads in which Robin is severely "drubbed" by a succession of professionals including a tanner, a tinker and a ranger.[5] In fact, the only character who does not get the better of Hood is the luckless Sheriff. Yet even in these ballads Robin is more than a mere simpleton: on the contrary, he often acts with great shrewdness. The tinker, setting out to capture Robin, only manages to fight with him after he has been cheated out of his money and the arrest warrant he is carrying. In Robin Hood's Golden Prize, Robin disguises himself as a friar and cheats two priests out of their cash. Even when Robin is defeated, he usually tricks his foe into letting him sound his horn, summoning the Merry Men to his aid. When his enemies do not fall for this ruse, he persuades them to drink with him instead.

The continued popularity of the Robin Hood tales is attested by a number of literary references. In William Shakespeare's comedy As You Like It, the exiled duke and his men "live like the old Robin Hood of England," while Ben Jonson produced the (incomplete) masque The Sad Shepherd, or a Tale of Robin Hood[23] as a satire on Puritanism. Somewhat later, the Romantic poet John Keats composed Robin Hood. To A Friend[24] and Alfred Lord Tennyson wrote a play The Foresters, or Robin Hood and Maid Marian,[25] which was presented with incidental music by Sir Arthur Sullivan in 1892. Later still, T. H. White featured Robin and his band in The Sword in the Stone—anachronistically, since the novel's chief theme is the childhood of King Arthur.[26]

The Victorian era generated its own distinct versions of Robin Hood. The traditional tales were often adapted for children, most notably in Howard Pyle's Merry Adventures of Robin Hood.[27] These versions firmly stamp Robin as a staunch philanthropist, a man who takes from the rich to give to the poor. Nevertheless, the adventures are still more local than national in scope: while Richard's participation in the Crusades is mentioned in passing, Robin takes no stand against Prince John, and plays no part in raising the ransom to free Richard. These developments are part of the twentieth century Robin Hood myth. The idea of Robin Hood as a high-minded Saxon fighting Norman Lords also originates in the 19th century. The most notable contributions to this idea of Robin are Thierry's Histoire de la Conquête de l'Angleterre par les Normands (1825), and Sir Walter Scott's Ivanhoe (1819). In this last work in particular, the modern Robin Hood—"King of Outlaws and prince of good fellows!" as Richard the Lionheart calls him—makes his début.[28]

The twentieth century has grafted still further details on to the original legends. The movie The Adventures of Robin Hood portrayed Robin as a hero on a national scale, leading the oppressed Saxons in revolt against their Norman overlords while Richard the Lion-Hearted fought in the Crusades; this movie established itself so definitively that many studios resorted to movies about his son (invented for that purpose) rather than compete with the image of this one.[28]

Since the 1980s, it has become commonplace to include a Saracen among the Merry Men, a trend which began with the character Nasir in the Robin of Sherwood television series. Later versions of the story have followed suit: the 1991 movie Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves and 2006 BBC TV series Robin Hood each contain equivalents of Nasir, in the figures of Azeem and Djaq respectively.[28]

The Robin Hood legend has thus been subject to numerous shifts and mutations throughout its history. Robin himself has evolved from a yeoman bandit to a national hero of epic proportions, who not only supports the poor by taking from the rich, but heroically defends the throne of England itself from unworthy and venal claimants.

List of traditional ballads

Ballads are the oldest existing form of the Robin Hood legends, although none of them are recorded at the time of the first allusions to him, and many are much later. They evince many common features, often opening with praise of the greenwood and relying heavily on disguise as a plot device, but include a wide variation in tone and plot.[5] The ballads below are sorted into three groups, very roughly according to date of first known free-standing copy. Ballads whose first recorded version appears (usually incomplete) in the Percy Folio may appear in later versions and may be much older than the mid-seventeenth century when the Folio was compiled. Any ballad may be older than the oldest copy which happens to survive, or descended from a lost older ballad. For example, the plot of Robin Hood's Death, found in the Percy Folio, is summarized in the fifteenth century A Gest of Robin Hood, and it also appears in an eighteenth century version.[9]

Early ballads

- A Gest of Robyn Hode

- Robin Hood and the Monk

- Robin Hood and the Potter

Percy Folio

- Little John a Begging

- Robin Hood's Death

- Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne

- Robin Hood and Queen Katherine

- Robin Hood and the Butcher

- Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar

- Robin Hood Rescuing Three Squires

- The Jolly Pinder of Wakefield

Other ballads

- A True Tale of Robin Hood

- Robin Hood and the Bishop

- Robin Hood and the Bishop of Hereford

- Robin Hood and the Golden Arrow

- Robin Hood and the Newly Revived

- Robin Hood and the Prince of Aragon

- Robin Hood and the Ranger

- Robin Hood and the Scotchman

- Robin Hood and the Tanner

- Robin Hood and the Tinker

- Robin Hood and the Valiant Knight

- Robin Hood Rescuing Will Stutly

- Robin Hood's Birth, Breeding, Valor and Marriage

- Robin Hood's Chase

- Robin Hood's Delight

- Robin Hood's Golden Prize

- Robin Hood's Progress to Nottingham

- The Bold Pedlar and Robin Hood

- The King's Disguise, and Friendship with Robin Hood

- The Noble Fisherman

Some ballads, such as Erlinton, feature Robin Hood in some variants, where the folk hero appears to be added to a ballad pre-existing him and in which he does not fit very well.[29] He was added to one variant of Rose Red and the White Lily, apparently on no more connection than that one hero of the other variants is named "Brown Robin."[30] Francis James Child indeed retitled Child ballad 102; though it was titled The Birth of Robin Hood, its clear lack of connection with the Robin Hood cycle (and connection with other, unrelated ballads) led him to title it Willie and Earl Richard's Daughter in his collection.[30]

Robin Hood (adaption)

Musical

- Robin Hood - Ein Abenteuer mit Musik (1995) - Festspiele Balver Höhle

Notes

- ↑ "Merry man" has referred to a follower of a knight or outlaw since the late fourteenth century, Merry man Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ↑ Robin Hood - On the move? BBC, January 2004. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ↑ Barbara Green, Dead in West Yorkshire? Robin Hood BBC, February 2003. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ↑ A Gest of Robin Hood stanzas 10-15 Sacred Texts. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 J. C. Holt, Robin Hood (Thames & Hudson, 1989, ISBN 0500275416).

- ↑ Brian Benison, Robin Hood-The Real Story (Leslie Brian Benison, 2004, ISBN 978-0954847302).

- ↑ Bob Curran, Walking with the Green Man: Father of the Forest, Spirit of Nature (New Page Books, 2007, ISBN 978-1564149312).

- ↑ William Langland, V.396 The vision of Piers Plowman. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 R. B. Dobson and J. Taylor (eds.), Rymes of Robin Hood (Sutton Publishing Ltd, 1997, ISBN 0750916613), 5.

- ↑ Maurice Keen, The Outlaws of Medieval England (Routledge, 2000, ISBN 978-0415239004).

- ↑ Walter Bower, Scotichronicon (1440), in Stephen T. Knight and Thomas Ohlgren (eds.), Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales (Medieval Institute Publications, 2000, ISBN 978-1580440677).

- ↑ Thomas Wright, Songs and Carols (Legare Street Press, 2022 (original 1847), ISBN 1019035080).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Stephen T. Knight and Thomas Ohlgren (eds.), Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales (Medieval Institute Publications, 2000, ISBN 978-1580440677).

- ↑ Thomas Ohlgren, Robin Hood: The Early Poems, 1465-1560 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2007, ISBN 978-1611493092).

- ↑ Robin Hood and the Monk Sacred Texts. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ↑ The Gest of Robyn Hode Sacred Texts. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Jeffrey Richards, Swordsmen of the Screen: From Douglas Fairbanks to Michael York (Routledge, 2016, ISBN 978-1138996663).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Allen W. Wright, A Beginner's Guide to Robin Hood Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ↑ Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun (Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0192854483).

- ↑ Ronald Hutton, The Rise and Fall of Merry England: The Ritual Year 1400-1700 (Oxford University Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0198203636).

- ↑ Anthony Munday, The Downfall of Robert Earl of Huntingdon (Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007 (original 1601), ISBN 978-0548750407).

- ↑ Joseph Ritson, Robin Hood: A Collection of All the Ancient Poems, Songs, and Ballads, Now Extant, Relative to That Celebrated English Outlaw: to Which Are Prefixed Historical Anecdotes of His Life (Wentworth Press, 2016 (original 1795), ISBN 978-1363290710).

- ↑ Ben Jonson, The Sad Shepherd: or, A Tale of Robin Hood University of Rochester. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ↑ John Keats, Robin Hood: To a Friend. University of Rochester. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ↑ Alfred Lord Tennyson, The Foresters: Robin Hood and Maid Marian. University of Rochester. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ↑ W.R. Irwin The Game of the Impossible (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1976, ISBN 978-0252005879).

- ↑ Howard Pyle, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (SeaWolf Press, 2018 (original 1883), ISBN 978-1949460520).

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Allen W. Wright, Wolfshead through the Ages. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ↑ Francis James Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Volume 1 (Andesite Press, 2017, ISBN 978-1375403146).

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Francis James Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Volume 2 (Dover Publications, 2003, ISBN 0486431460).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Benison, Brian. Robin Hood-The Real Story. Leslie Brian Benison, 2004. ISBN 978-0954847302

- Child, Francis James. The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Volume 1. Andesite Press, 2017. ISBN 978-1375403146

- Child, Francis James. The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Volume 2. Dover Publications, 2003. ISBN 0486431460

- Curran, Bob. Walking with the Green Man: Father of the Forest, Spirit of Nature. New Page Books, 2007. ISBN 978-1564149312

- Dobson, John, and R.B. Taylor (eds.). Rymes of Robyn Hood: An Introduction to the English Outlaw. Sutton Publishing Ltd, 1997. ISBN 0750916613

- Holt, J. C. Robin Hood. Thames & Hudson, 1989. ISBN 0500275416

- Hutton, Ronald. The Rise and Fall of Merry England: The Ritual Year 1400-1700. Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0198203636

- Hutton, Ronald. The Stations of the Sun. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0192854483

- Irwin, W.R. The Game of the Impossible. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0252005879

- Keen, Maurice. The Outlaws of Medieval England. Routledge, 2000. ISBN 978-0415239004

- Knight, Stephen T., and Thomas Ohlgren. Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales. Medieval Institute Publications, 2000. ISBN 978-1580440677

- Munday, Anthony. The Downfall of Robert Earl of Huntingdon. Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007 (original 1601). ISBN 978-0548750407

- Ohlgren, Thomas. Robin Hood: The Early Poems, 1465-1560. (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1611493092

- Pyle, Howard. The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood. SeaWolf Press, 2018 (original 1883). ISBN 978-1949460520

- Richards, Jeffrey. Swordsmen of the Screen: From Douglas Fairbanks to Michael York. Routledge, 2016. ISBN 978-1138996663

- Ritson, Joseph. Robin Hood: A Collection of All the Ancient Poems, Songs, and Ballads, Now Extant, Relative to That Celebrated English Outlaw: to Which Are Prefixed Historical Anecdotes of His Life. Wentworth Press, 2016 (original 1795). ISBN 978-1363290710

- Wright, Thomas. Songs and Carols. Legare Street Press, 2022 (original 1847). ISBN 1019035080

External links

All links retrieved March 2, 2023.

- Robin Hood and his Historical Context BBC

- Robin Hood: Bold Outlaw of Barnsdale and Sherwood

- The Robin Hood Project University of Rochester

- A Beginner's Guide to Robin Hood by Allen W. Wright

- Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales edited by Stephen Knight and Thomas H. Ohlgren. University of Rochester.

| |||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.