Pol Pot

| Saloth Sar "Pol Pot" | |

Pol Pot's bust at Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum | |

General Secretary of the Communist Party of Kampuchea

| |

| In office 1963 – 1979 | |

| Preceded by | Tou Samouth |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | None (party dissolved) |

Prime Minister of Democratic Kampuchea (Cambodia)

| |

| In office May 13, 1975 – January 7, 1979 | |

| Preceded by | Khieu Samphan |

| Succeeded by | Pen Sovan |

| Born | May 19 1925 Kampong Thum Province, Cambodia |

| Died | April 15 1998 (aged 72) Cambodia |

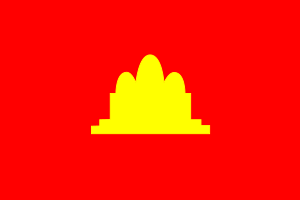

| Political party | Khmer Rouge |

| Spouse | Khieu Ponnary (deceased) Mea Son |

Pol Pot (May 19, 1925 – April 15, 1998), earlier known as Saloth Sar, was leader of the Communist movement known as the "Khmer Rouge" and is considered largely responsible for drastic policies of collectivization and terror a huge segment of the population of Cambodia perished in the mid-to-late 1970s.

After leading joining the communist movement while a student in France and leading the Khmer Rouge rebels in the early 70s, Pol Pot became the prime minister of "Democratic Kampuchea" from 1976 to 1979, having been de facto leader since mid-1975. During his time in power he imposed a version of agrarian collectivization whereby city dwellers were relocated to the countryside to work in collective farms and other forced labor projects with the goal of restarting civilization in "Year Zero." Students, landlords, government works, teachers, shop-owners, and ethnic minorities were treated as enemies of the revolution and were slaughtered on a mass scale in the Khmer Rouge's infamous "killing fields." The combined effect of slave labor, intentional starvation, poor medical care, and mass executions resulted an estimated death toll of 750,000 to 3 million people.

In 1979, Pol Pot fled into the jungles of southwest Cambodia after an invasion by neighboring Vietnam, which led to the collapse of the Khmer Rouge government. There he continued to resist the new government until 1997, when he was overthrown and imprisoned by other Khmer Rouge leaders and died in 1998 while under house arrest. He is considered one of the worst mass murderers in history.

Biography

Early life (1925-1961)

Saloth Sar was born in Prek Sbauv in Kampong Thom Province in 1925 to a moderately wealthy family of Chinese-Khmer descent. In 1935, his family sent him to live with an older brother and a Catholic school in Phnom Penh. His sister was a concubine of the king, and he often visited the royal palace. In 1947, he gained admission to the exclusive Lycée Sisowath, but was unsuccessful in his studies.

After switching to a technical school, he qualified for a scholarship that allowed him to study in France. He studied radio electronics in Paris from 1949 to 1953. During this time he participated in an international labor brigade building roads in Yugoslavia in 1950.

After the Soviet Union recognized the Viet Minh as the government of Vietnam in 1950, French Communists (PCF) attracted many young Cambodians, including Saloth. In 1951, he joined a communist cell in a secret organization known as the Cercle Marxiste, which had taken control of the Khmer Student's Association and also joined the PCF itself.

As a result of failing his exams in three successive years, Saloth was forced to return to Cambodia in January 1954, where he worked as a teacher. As the first member of the Cercle to return to Cambodia and was given the task of evaluating the various groups rebelling against the government. He selected the Khmer Viet Minh as the most promising, and in August 1954, he traveled to the Viet Minh Eastern Zone headquarters in the Kampong Cham/Prey Veng border area of Cambodia.

After to the Geneva peace accord of 1954 granted Cambodian independence, Saloth, returned to Phnom Penh, where various right and left wing parties struggled against each other for power in the new government. King Norodom Sihanouk played the parties against each other while using the police and army to suppress extreme political groups. Saloth became the liaison between the above-ground parties of the left and the underground Communist movement.

The path to rebellion (1962-1968)

In January 1962, Saloth could become the de facto deputy leader of the Cambodian Communist party after the death of Ton Samouth and was formally elected secretary of the central committee of the party the following year. In March, Saloth went into hiding after his name was published in a police list of leftist revolutionary suspects. He fled to the Vietnamese border region and made contact with Vietnamese units fighting against South Vietnam.

In early 1964, Saloth convinced the Vietnamese to help the Cambodian Communists set up their own base camp in the area. The central committee of the party met later that year and issued a declaration calling for armed struggle. The declaration also emphasized the idea of "self-reliance" in the sense of extreme Cambodian nationalism. In the border camps, the ideology of the Khmer Rouge was gradually developed. Breaking with classical Marxism, the party followed the Maoist line and declared rural peasant farmers to be the true lifeblood of the revolution.

After another wave of repression by Sihanouk in 1965, the Khmer Rouge movement began to grow more rapidly. Many teachers and students left the cities for the countryside to join the movement. In April 1965, Saloth went to North Vietnam to gain approval for an uprising in Cambodia against the government. However, North Vietnam refused to support any revolt, with Sihanouk promising to allow the Vietnamese Communists to use Cambodian territory and ports in their war against South Vietnam.

After returning to Cambodia in 1966, Saloth organized a party meeting in which the organization was officially but secretly renamed the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and command zones were established to prepare each region for an uprising against the government.

In early 1966 a dispute over the government price paid for rice resulted in violent confrontations between the peasants and government forces. Saloth's Khmer Rouge was caught by surprise by the uprisings, but the government's hard-line tactics in the episodes created rural unrest that played into the hands of the Communist movement.

In 1967 Saloth decided to launch a national uprising, even without North Vietnamese support. The revolt began on January 18, 1968 with a raid on an army base south of Battambang, which had already seen two years of peasant unrest. The attack was repulsed, but the Khmer Rouge captured a number of weapons, which were then used to drive police forces out of various Cambodian villages.

By the summer of 1968, Saloth began the transition from a collective leadership toward being the sole decision-maker of of the Khmer Rouge movement. Where before he had shared communal quarters with other leaders, he now had his own compound with a personal staff and a troop of guards. People outside his inner circle were no longer allowed to approach him, but had to be summoned into his presence by his staff.

The path to power (1969-1975)

The movement at this time consisted of about 1500 regulars, but was supported by a considerably larger number of villagers. While weapons were in short supply, the insurgency was able to operate in 12 of 19 districts of Cambodia. Up to 1969, opposition to Sihanouk was at the center of Khmer Rouge propaganda. However, it now ceased to be anti-Sihanouk in public statements and shifted its criticism to the right-wing parties of Cambodia and the "imperialist" United States.

Then, in 1970, the Cambodian National Assembly voted to remove Sihanouk from office and ceased all cooperation with North Vietnam. The country's new president was the staunchly pro-U.S. General Lon Nol. The North Vietnamese reacted to the political changes in Cambodia by sending Premier Phạm Văn Đồng to meet Sihanouk in China and recruit him into an alliance with the Khmer Rouge. The Vietnamese now offered Saloth whatever resources he wanted for his insurgency against the Cambodian government. Sihanouk soon appealed by radio to the people of Cambodia to rise up against the government and support the Khmer Rouge. In May 1970, Saloth returned to Cambodia and the pace of the insurgency greatly increased. Meanwhile, a force of 40,000 Vietnamese quickly overran large parts of eastern Cambodia, reaching to within 15 miles (24 km) of Phnom Penh before being pushed back. In these battles, however, the Khmer Rouge and Saloth played a very small role.

Through 1971, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong did most of the fighting against the Cambodian government while Saloth and the Khmer Rouge functioned virtually as auxiliaries to their forces. Saloth took advantage of the situation to gather in new recruits and to train them to a higher standard than previously was possible. He also put the resources of Khmer Rouge organizations into political education and indoctrination. Requirements for membership in the party, were made more strict, with students and so-called "middle peasants" refused admission, while senior party leadership, including Saloth himself ironically came from student and middle peasant backgrounds.

By 1972, a Khmer Rouge army of 35,000 men had taken shape, supported by around 100,000 irregulars. China was supplying 5 million dollars a year in weapons, and Saloth had organized an independent revenue source for the party in the form of rubber plantations in eastern Cambodia, using forced labor.

In May 1972, Saloth began to enforce new levels of discipline and conformity in areas under Khmer Rouge control. The Chams and other minorities were forced to conform to Cambodian styles of dress and appearance, and all land holdings were required to be of uniform size. The party also confiscated all private means of transportation. Saloth issued a new set of decrees in May 1973 which started the process of reorganizing peasant villages into cooperatives where property was jointly owned and individual possessions banned.

Saloth issued orders during the peak of the rainy season that the city of Phnom Penh be taken. The attack failed, but by the middle of 1973, the Khmer Rouge controlled almost two-thirds of the country and half the population. North Vietnam now began to treat Saloth as more of an equal leader than a junior partner.

In late 1973, Saloth moved to cut the capital off from contact from outside supply and effectively put the city under siege. He also began to tightly control the flow out of the city through the Khmer Rouge lines. Under Khmer Roughe peasant-centered ideology, city people were considered like a disease that needed to be contained so that it would not infect areas run by the Khmer Rouge.

Around this time, Saloth also ordered a series of general purges within the party, targeting former government officials workers and officials, teachers, and virtually anyone with an education. A set of new prisons was also constructed in Khmer Rouge-run areas. A Cham uprising was quickly crushed, and Saloth ordered harsh physical torture against most of those involved in the revolt.

The Khmer Rouge policy of of emptying urban areas to the countryside was also instituted around this time. In 1973, after attempts to impose socialism in the town of Kratie had met with failure several times, Saloth decided that the only solution was to send the entire population of the town to the fields. Shortly after this, Saloth ordered the evacuation of the 15,000 people of Kompong Cham for the same reasons. The larger city of Oudong was forcibly evacuated in 1974.

Internationally, Saloth and the Khmer Rouge were able to gain the recognition of 63 pro-Communist countries as the true government of Cambodia. A move at the United Nations to give the seat for Cambodia to the Khmer Rouge failed by only two votes.

In September 1974, Saloth gathered the central committee of the party to implement a series of decisions. First, it was decided that after the government was overthrown, the main cities of the country would be evacuated with the population moved to the countryside. The second was that no new money would be put into circulation and that money would quickly be phased out as a means of exchange. Finally, the committee instituted a major purge of party ranks. A top party official named Prasith was taken out into a forest and shot to death without trial. His death was followed by a purge of cadres who, like Prasith, were ethnically Thai.

The Khmer Rouge were positioned for a final offensive against the government in January 1975. However, North Vietnam was determined to take Saigon before the Khmer Rouge took Phnom Penh. Shipments of weapons from China were delayed, but with the U.S. withdrawing its support, the government could see the writing on the wall. In September, the government formed a Supreme National Council with new leadership, with the aim of negotiating a surrender to the Khmer Rouge. It was headed by Sak Sutsakhan, who had studied in France with Saloth and was cousin to the Khmer Rouge Deputy Secretary Nuon Chea. Saloth's reaction to this was to add the names of everyone involved to his post-victory death list.

Democratic Kampuchea (1975-1979)

The Khmer Rouge took Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975. Saloth Sar called himself the "brother number one" and declared his nom de guerre Pol Pot, from the FrenchPolitique potentielle. A new government was formed, at first with Khieu Samphan as prime minister under the control of the party. Khieu was obliged relinquish the post to Pol Pot on May 13, making Pol Pot the de facto dictator of Cambodia. Khieu became titular head of state after the formal abdication of Sihanouk in January 1976, as a new constitution was adapted and a republic proclaimed.

The name of the country was now officially changed to Democratic Kampuchea. The Khmer Rouge now targeted Buddhist monks, Muslims, Western-educated intellectuals, University students and teachers, people who had contact with Western countries or with Vietnam, the crippled and lame, and the ethnic Chinese, Laotians and Vietnamese. Some of these "enemies of the people" were put in the infamous S-21 camp for interrogation, often involving torture in cases where a confession was useful to the government. Many others were summarily executed.

Immediately after the fall of Phnom Penh, the Khmer Rouge had begun to implement reforms following the concept of "Year Zero" ideology. They ordered the complete evacuation of Phnom Penh and all other recently captured major towns and cities. Those leaving were reportedly told that the evacuation was due to the threat of severe American bombing and it would last for no more than a few days.

In 1976, people were reclassified as "full-rights" (base) people, "candidates," and "depositees"—so called because they included most of the new people who had been deposited from the cities into the rural communes. Depositees were marked for destruction. Their rations were reduced to two bowls of rice soup per day, leading to widespread starvation.

Hundreds of thousands of the depositees and other "non-revolutionary" people were taken out in shackles to dig their own mass graves. The Khmer Rouge soldiers then beat them to death with iron bars and hoes or buried them alive. A Khmer Rouge extermination prison directive ordered, "Bullets are not to be wasted." These mass graves are often referred to as The Killing Fields.

The Khmer Rouge also classified people by religion and ethnic group. Despite Cambodia's ancient Buddhist culture, they officially abolished all religion and dispersed minority groups, forbidding them to speak their languages or to practice their customs.

All property became collective, and education was dispensed at communal schools. The family as the primary institution of society was abolished , and children were raised on a communal basis. Political dissent and opposition were strictly prohibited. People were often treated as enemies of the revolution based on their appearance or background. Torture was widespread. Thousands of politicians and bureaucrats accused of association with previous governments were executed. Phnom Penh was turned into a ghost city, while people in the countryside were dying of starvation, illnesses, or execution.

The death toll from Pol Pot's policies is a matter of debate. Estimates vary from a low of 750,000 to as many as three million. Amnesty International estimated 1.4 million; and the United States Department of State, 1.2 million. Cambodia had a total estimated population at the time of around 5 million.

Internationally, Pol Pot aligned the country with the People's Republic of China and adopted an anti-Soviet line. In December 1976, Pol Pot issued directives to the senior leadership to the effect that Vietnam was now an enemy. Defenses along the border were strengthened and unreliable deportees were moved deeper into Cambodia.

Conflict with Vietnam

In January 1977, relations with Vietnam deteriorated with small clashes and border disputes. On April 30, the Cambodian army, backed by artillery, crossed over into Vietnam, and in May the Vietnamese retaliated by sending air raids. In September, Cambodia launched division-scale raids over the border leaving a trail of mass killings and destruction in villages which resisted them. In December, Vietnam sent a large number of troops into Cambodia, but the they was soon forced to withdraw. After negotionations failed to produce an agreement, Vietnam decided began to prepare for full-scale war.

In late 1978, Vietnam invaded Cambodia with the intent of overthrowing the Khmer Rouge. The Cambodian army was defeated, and Pol Pot fled to the Thai border area. In January 1979, Vietnam installed a new government under Heng Samrin, composed mostly of Khmer Rouge who had previously fled to Vietnam to avoid the Pol Pot's purges. Pol Pot, meanwhile, regrouped with his core supporters in locations on both sides of the Thai border, with Chinese material support and the military government of Thailand using his Khmer Rouge as a buffer force to keep the Vietnamese away from the border. Vietnam did not move decisively to root out the Khmer Rouge and used the continued existence of Pol Pot's forces to justify continued military occupation of the Combodia.

Aftermath (1979-1998)

In the early 1980s, Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge remained the best-trained and most capable of the three insurgent groups who, despite sharply divergent ideologies, formed the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK) alliance three years earlier. Finally, in December 1984, the Vietnamese launched a major offensive and overran most of the Khmer Rouge and other insurgent positions. Pol Pot fled to Thailand where he lived for six years under Thai protection.

Pol Pot officially resigned as head of the party 1985 but, handed day to day power to Son Sen, but continued as de facto Khmer Rouge leader and dominant force within the anti-Vietnam alliance. In 1986, his new wife, Mea Son, gave birth to a daughter, Sitha. Shortly after, Pol Pot moved to China for medical treatment for cancer of the face. He remained there until 1988.

In 1989, Vietnam withdrew its occupation force from Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge established a new stronghold area in the west near the Thai border and Pol Pot relocated back into Cambodia from Thailand. The Khmer Rouge kept the government forces at bay until 1996, when troops started deserting and several important Khmer Rouge leaders also defected. In 1995, meanwhile, Pol Pot experienced a stroke that paralyzed the left side of his body.

After Son Sen attempted to make a settlement with the government Pol Pot had him executed on June 10, 1997. Eleven members of his family were also killed. Pol Pot then fled his northern stronghold, but was later arrested by Khmer Rouge military Chief Ta Mok, who subjected him to a show trial for the death of Son Sen. He was sentenced to lifelong house arrest.

Death and legacy

On the night of April 15, 1998 the Voice of America, of which Pol Pot was a devoted listener, announced that the Khmer Rouge had agreed to turn him over to an international tribunal. According to his wife, he died in his bed later in the night while waiting to be moved to another location. His body was cremated without an autopsy a few days later at Anlong Veng in the Khmer Rouge zone, raising strong suspicions that he committed suicide or was poisoned.

Pol Pot's legacy in Cambodia is one of mass murder and genocide on a scale unprecedented in relation to the size of his country. His application of Leninist-Maoist principles, justifying "any means" to achieve revolutionary ends, resulted in the most hideous Communist regime in history, famous for its "killing fields" in which men, women, and children were slaughtered on a massive scale by Khmer Rouge troops who had been indoctrinated into Pol Pot's vision of "Year Zero." He ranks with Hitler, Stalin, and Mao, as one of the greatest mass murderers in modern history.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Affonço, Denise. 2007. To The End Of Hell: One Woman's Struggle to Survive Cambodia's Khmer Rouge. (With Introductions by Jon Swain and David P. Chandler.) London: Reportage Press. ISBN 9780955572951

- Short, Philip. 2005. Pol Pot: Anatomy of a Nightmare. NY: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-6662-4

- Chandler, David P, Kiernan, Ben and Boua, Chanthou. 1988. Pol Pot plans the future: Confidential leadership documents from Democratic Kampuchea, 1976-1977. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-938692-35-6

- Chandler, David P. 1992. Brother Number One: A political biography of Pol Pot. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3510-8

- Dith Pran, and Kim DePaul. 1997. Children of Cambodia's killing fields memoirs by survivors. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780585347608

- Heder, Stephen. 1991. Pol Pot and Khieu Samphan. Clayton, Victoria: Centre of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 0-7326-0272-6

- Kiernan, Ben. 1997. The Pol Pot regime: Race, power and genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300061130

- _____________. 2004. How Pol Pot came to power: A history of Cambodian communism, 1930-1975. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10262-3

- Ponchaud, François. 1978. Cambodia: Year Zero. NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 9780030403064

- Vickery, Michael. 1984. Cambodia: 1975-1982. Boston: South End Press. ISBN 9780896081895

External links

- A meeting with Pol Pot

- Interview with biographer P. Short, UCLA International Institute

- Cambodian Genocide Program, 1994-2008

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.