Difference between revisions of "Pictogram" - New World Encyclopedia

Nick Perez (talk | contribs) |

Nick Perez (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

As the use of pictograms increased, so to did their meaning. Certain signs came to indicate names of gods, countries, cities, vessels, birds, trees, etc. These are known as "[[determinative|determinants]]," and were the Sumerian signs of the terms in question, added as a guide for the reader. Proper names continued to be usually written in purely "ideographic" fashion.<ref>Mieroop, Marc Va. ''Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History". Routledge 1999. ISBN 0415195330</ref> From about 2900 B.C.E., many pictographs began to lose their original function, and a given sign could have various meanings depending on context. The sign inventory was reduced from some 1,500 signs to some 600 signs, and writing became increasingly phonological. [[Determinative]] signs were re-introduced to avoid ambiguity.<ref>Mieroop, Marc Va. ''Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History". Routledge 1999. ISBN 0415195330</ref> | As the use of pictograms increased, so to did their meaning. Certain signs came to indicate names of gods, countries, cities, vessels, birds, trees, etc. These are known as "[[determinative|determinants]]," and were the Sumerian signs of the terms in question, added as a guide for the reader. Proper names continued to be usually written in purely "ideographic" fashion.<ref>Mieroop, Marc Va. ''Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History". Routledge 1999. ISBN 0415195330</ref> From about 2900 B.C.E., many pictographs began to lose their original function, and a given sign could have various meanings depending on context. The sign inventory was reduced from some 1,500 signs to some 600 signs, and writing became increasingly phonological. [[Determinative]] signs were re-introduced to avoid ambiguity.<ref>Mieroop, Marc Va. ''Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History". Routledge 1999. ISBN 0415195330</ref> | ||

| − | + | Pictograms were also used by the ancient Chinese culture since around 5000 B.C.E. and began to develop into [[logogram|logographic]] [[writing system]]s around 2000 B.C.E.<ref>(2002) Wu, W. Wu: Chinese [http://www.ocf.berkeley.edu/~wwu/chinese/pictograms.shtml"Chinese:Pictograms"] Retrieved July 10, 2008</ref> | |

Though written [[Chinese written language|Chinese]] is often thought of consisting of pictograms, less than 4% of all [[Chinese character|characters]] ever created have their direct origins in pictograms. The letters of the [[Roman alphabet]], however, do have their origins in pictograms. For example, the letter ''A'' represented the head of an ox, and if it is turned upside down, a bovine head with horns can be seen. | Though written [[Chinese written language|Chinese]] is often thought of consisting of pictograms, less than 4% of all [[Chinese character|characters]] ever created have their direct origins in pictograms. The letters of the [[Roman alphabet]], however, do have their origins in pictograms. For example, the letter ''A'' represented the head of an ox, and if it is turned upside down, a bovine head with horns can be seen. | ||

Revision as of 02:28, 11 July 2008

Writing systems |

|---|

| History |

| Types |

| Alphabet |

| Abjad |

| Abugida |

| Syllabary |

| Logogram |

| Related |

| Pictogram |

| Ideogram |

A pictogram or pictograph is a symbol representing a concept, object, activity, place or event by illustration.[1] Pictography is a form of writing in which ideas are transmitted through drawing.[2] It is the basis for some of the earliest forms of structured written languages, such as Cuneiform and, to some extent, Hieroglyphs.

Pictograms are still in use as the main medium of written communication in some non-literate cultures in Africa, The Americas, and Oceania. Pictograms are also often used as simple symbols by most contemporary cultures.

Etymology

Both pictogram and pictography share the same Latin root, pict(us), which roughly translates as "painting". Combined with the word gram, which was the Greek word used for the smallest unit of measurement, pictogram thus means a single painting or picture.[3] Graphy, the Greek word for "the act of writing or painting" combines with pict(us) to form pictography, which thus refers to the act of creating a painting or picture.[4]

Earliest use

The earliest pictograms were in use in Mesopotamia and predated the famous Sumerian cuneiforms (the oldest of which date to around 3400 B.C.E.). As early as 9000 B.C.E. pictograms were used on tokens that were placed on farm produce.[5] As civilization advanced, creating cities and more complex economic systems, more complex pictographic tokens were devised and used on labels for manufactured goods. Pictograms eventually evolved from simple labels into a more complex structure of written language, and were written on clay tablets. Marks and pictures were made with a blunt reed called a stylus, the impressions they made were wedge shaped.[6]

As the use of pictograms increased, so to did their meaning. Certain signs came to indicate names of gods, countries, cities, vessels, birds, trees, etc. These are known as "determinants," and were the Sumerian signs of the terms in question, added as a guide for the reader. Proper names continued to be usually written in purely "ideographic" fashion.[7] From about 2900 B.C.E., many pictographs began to lose their original function, and a given sign could have various meanings depending on context. The sign inventory was reduced from some 1,500 signs to some 600 signs, and writing became increasingly phonological. Determinative signs were re-introduced to avoid ambiguity.[8]

Pictograms were also used by the ancient Chinese culture since around 5000 B.C.E. and began to develop into logographic writing systems around 2000 B.C.E.[9] Though written Chinese is often thought of consisting of pictograms, less than 4% of all characters ever created have their direct origins in pictograms. The letters of the Roman alphabet, however, do have their origins in pictograms. For example, the letter A represented the head of an ox, and if it is turned upside down, a bovine head with horns can be seen.

Modern use

Pictograms were extensively used on a London Suburban map of the London & North Eastern Railway map in 1937, and remain in common use today, serving as signs or instructions. Because of their graphical nature and fairly realistic style, they are widely used to indicate public toilets, or places such as airports and train stations. However, even these symbols are highly culture-specific. For example, in some cultures men commonly wear dress-like clothing, so even restroom signage is not universal.

A standard set of pictograms was defined in the international standard ISO 7001: Public Information Symbols. Another common set of pictograms are the laundry symbols used on clothing tags and chemical hazard labels. Pictography hinders search-engine capability, requiring symbol searching, while text-based writing also facilitates spoken words, even new words by use of pronunciation rules, and text enables sorting information alphabetically.

Pictographic writing as a modernist poetic technique is credited to Ezra Pound though French surrealists accurately credit the Pacific Northwest American Indians of Alaska who introduced writing, via totem poles, to North America (Reed 2003, p. xix).

Pictograms can also be seen in various crop circles.

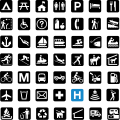

DOT pictograms

The DOT pictograms are a set of fifty pictograms used to convey information useful to travelers without using words. Such images are useful in airports, train stations, hotels, and other public places for foreign tourists, as well as being easier to identify than strings of text. Among these pictograms are the now-familiar graphics representing toilets and telephones. As a result of this near-universal acceptance, some describe them as the "Helvetica" of pictograms, and the character portrayed within them as Helvetica Man (Lupton).

As works of the United States government, the images are in the public domain and thus can be used by anyone for any purpose, without licensing issues.

In 1974, the United States Department of Transportation (DOT) recognized the shortcomings of pictograms drawn on an ad hoc basis across the United States Interstate Highway System and commissioned the American Institute of Graphic Arts to produce a comprehensive set of pictograms. In collaboration with Roger Cook and Don Shanosky of Cook and Shanosky Associates, the designers conducted an exhaustive survey of pictograms already in use around the world, which drew from sources as diverse as Tokyo International Airport and the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. The designers rated these pictograms based on criteria such as their legibility, their international recognizability and their resistance to vandalism. After determining which features were the most successful and appropriate, the designers drew a set of pictograms to represent 34 meanings requested by the DOT.

In 1979, 16 symbols were added, bringing the total to 50.

ISO 7001

ISO 7001 ("Public information symbols") is a standard published by the International Organization for Standardization that defines a set of pictograms and symbols for public information. The latest version, ISO 7001:2007, has been published in November 2007.

The set is the result of extensive testing in several countries and different cultures and have met the criteria for comprehensibility set up by the ISO. Common examples of public information symbols include those representing toilets, car parking, and information, and the International Symbol of Access.

Sample National Park Service pictographs

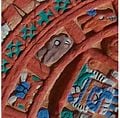

Pictograph from 1510 telling a story of coming of missionaries to Hispaniola

Water, rabbit, deer pictograms on a replica of an Aztec Stone of the Sun

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ellen Lupton and J. Abbott Miller. Design Writing Research: Writing About Graphic Design. New York: Kiosk, 1996.

- The Professional Association for Design for the U.S. Department of Transportation. Symbol signs, 2nd ed. New York: American Institute of Graphic Arts, 1993.

- Reed, Ishmael (2003). From Totems to Hip-Hop: A Multicultural Anthology of Poetry Across the Americas, 1900-2002, Ishmael Reed, ed. ISBN 1-56025-458-0.

External links

- DOT pictograms (symbol signs)

- Airport, an animated film made from AIGA pictograms

- Purchase the ISO 7001:2007 standard

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ pictogram. (n.d.). The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Retrieved July 10, 2008, from Dictionary.com website: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/pictogram

- ↑ pictography. (n.d.). Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Retrieved July 10, 2008, from Dictionary.com website: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/pictography

- ↑ pictogram. (n.d.). Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Retrieved July 10, 2008, from Dictionary.com website: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/pictogram

- ↑ pictography. (n.d.). Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Retrieved July 10, 2008, from Dictionary.com website: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/pictography

- ↑ (2006) Center for Instructional Innovation, Western Washington University "The Invention of Writing" Retrieved July 10, 2008

- ↑ (2006) Center for Instructional Innovation, Western Washington University "The Invention of Writing" Retrieved July 10, 2008

- ↑ Mieroop, Marc Va. Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History". Routledge 1999. ISBN 0415195330

- ↑ Mieroop, Marc Va. Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History". Routledge 1999. ISBN 0415195330

- ↑ (2002) Wu, W. Wu: Chinese "Chinese:Pictograms" Retrieved July 10, 2008