Occupation of Japan

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

At the end of the Second World War, a ravaged Japan was occupied by the Allied Powers, led by the United States with contributions also from Australia, British India, the United Kingdom and New Zealand. This foreign presence marked the first time since the unification of Japan that the island nation had been occupied by a foreign power. The San Francisco Peace Treaty, signed on September 8, 1951, marked the end of the Allied occupation, and subsequent to its coming into force on April 28, 1952, Japan was once again an independent state. The U.S. ended the occupation in part to address concerns in Korea as well as out of a larger overall fear of the rise of communism in various nations around the globe. The occupation period saw the USA venture into nation-building, which can be regarded as an extension of manifest destiny onto the international arena. The mission to strengthen democracy in Japan and elsewhere was wholly consistent with the reason America, and the Allied Powers (World War II) Allies of World War II found themselves confronting the Axis Powers, that is, to defeat totalitarianism, Fascism and tyranny in defense of democracy and freedom. Having launched the democratization process, the USA left Japan, in sharp contrast to the way in which the Soviet Union, in what became its post-World War II sphere of influence in East Europe, manufactured puppet, proxy communist regimes and never left until. losing the Cold War, this empire collapsed.

Surrender

On August 6, 1945 an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, followed by a subsequent atomic bomb attack on Nagasaki on August 9.[1] The attacks reduced these cities to rubble and killed and maimed vast numbers of civilians. Largely in response to devastation caused by the new weapon, Japan initially surrendered to the Allies on August 14, 1945, when Emperor Hirohito accepted the terms of the Potsdam Declaration.[2] On the following day, Hirohito announced Japan's surrender on the radio.

The announcement was the emperor's first ever radio broadcast and the first time most citizens of Japan ever heard their sovereign's voice.[3] This date is known as Victory Over Japan, or V-J Day, and marked the end of World War II and the beginning of a long road to recovery for a shattered Japan.

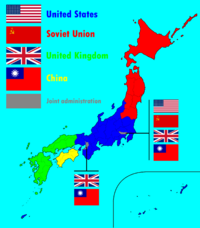

On V-J Day, United States President Harry Truman appointed General Douglas MacArthur as Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP), to supervise the occupation of Japan.[4] Due to his physical appearance, MacArthur, an American war hero, was dubbed "blue-eyed shogun" and "Japan's Saviour" during his tenure in the occupied nation.[5] During the war, the Allied Powers had planned to divide Japan amongst themselves for the purposes of occupation, as was done for the occupation of Germany. Under the final plan, however, SCAP was given direct control over the main islands of Japan (Honshū, Hokkaidō, Shikoku and Kyūshū) and the immediately surrounding islands,[6] while outlying possessions were divided between the Allied Powers as follows:

- Soviet Union: North Korea (not a full occupation), Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands

- United States: South Korea (not a full occupation), Okinawa, the Amami Islands, the Ogasawara Islands and Japanese possessions in Micronesia

- Republic of China: Taiwan and the Pescadores

It is unclear why the occupation plan was changed. Common theories include the increased power of the United States following development of the atomic bomb, Truman's greater distrust of the Soviet Union when compared with Roosevelt, and an increased desire to contain Soviet expansion in the Far East after the Yalta Conference.

The Soviet Union had some intentions of occupying Hokkaidō.[7] Had this occurred, there might have been the foundation of a communist "Democratic People's Republic of Japan" in the Soviet zone of occupation. However, unlike the Soviet occupations of East Germany and North Korea, these plans were frustrated by the opposition of President Truman.[8]

The Far Eastern Commission and Allied Council For Japan were also established to supervise the occupation of Japan.[9] Japanese officials left for Manila on August 19 to meet MacArthur and to be briefed on his plans for the occupation. On August 28, 150 U.S. personnel flew to Atsugi, Kanagawa Prefecture. They were followed by USS Missouri, whose accompanying vessels landed the 4th Marine Division on the southern coast of Kanagawa. Other Allied personnel followed.

MacArthur arrived in Tokyo on August 30,[10] and immediately decreed several laws: No Allied personnel were to assault Japanese people. No Allied personnel were to eat the scarce Japanese food. Flying the Hinomaru or "Rising Sun" flag was initially severely restricted (although individuals and prefectural offices could apply for permission to fly it). The restriction was partially lifted in 1948 and completely lifted the following year. The Hinomaru was the de facto albeit not de jure flag throughout World war II and the occupation period.[11] During the early years of the occupation, its use was temporarily restricted to various degrees. Sources differ on the use of the terms "banned" and "restricted." John Dower discusses the use of "banned": " ...the rising sun flag and the national anthem, both banned by GHQ..[12] " ...Even ostensible Communists found themselves waving illegal rising-sun flags."[13] Steven Weisman goes on to note that "... the flag... [was] banned by Gen. Douglas A. MacArthur, Supreme Commander and administrator of Japan after the war."[14] Other sources offer a more detailed and nuanced explication, as for example Christopher Hood: "After the war, SCAP (Supreme Command Allied Powers) had stopped the use of Hinomaru... However, in 1948, it was decided that Hinomaru could be used on national holidays, and all other restrictions were lifted the following year."[15] Further information is given by D. Cripps: "...[before 1948] by notifying the occupation forces in an area, individuals could apply to raise the flag and, depending on the national holiday and region, the prefectural office could be given permission to raise the flag."[16] Moreover, Goodman and Refsing use the phrase "restricted, though not totally banned" and further note that flying the flag was considered anathema by many Japanese themselves in the postwar decades, and its use has been a subject of national debate.[17] See Flag of Japan for more information.

On September 2, Japan formally surrendered with the signing of the Japanese Instrument of Surrender aboard the USS Missouri.[18] Allied (primarily American) forces were set up to supervise the country.[19] General MacArthur was technically supposed to defer to an advisory council set up by the Allied powers but in practice did everything himself. His first priority was to set up a food distribution network; following the collapse of the ruling government and the wholesale destruction of most major cities virtually everyone was starving. Even with these measures, millions of people were still on the brink of starvation for several years after the surrender.[20][21]

Once the food network was in place, at a cost of up to US$1 million per day, MacArthur set out to win the support of Hirohito. The two men met for the first time on September 27; the photograph of the two together is one of the most famous in Japanese history. However, many were shocked that MacArthur wore his standard duty uniform with no tie instead of his dress uniform when meeting the emperor. MacArthur may have done this on purpose, to send a message as to what he considered the emperor's status to be.[22] With the sanction of Japan's reigning monarch, MacArthur had the ammunition he needed to begin the real work of the occupation. While other Allied political and military leaders pushed for Hirohito to be tried as a war criminal, MacArthur resisted such calls and rejected the claims of members of the imperial family such as Prince Mikasa and Prince Higashikuni and intellectuals like Tatsuji Miyoshi who asked for the emperor's abdication,[23] arguing that any such prosecution would be overwhelmingly unpopular with the Japanese people.[24]

By the end of 1945, more than 350,000 U.S. personnel were stationed throughout Japan. By the beginning of 1946, replacement troops began to arrive in the country in large numbers and were assigned to MacArthur's Eighth Army, headquartered in Tokyo's Dai-Ichi building. Of the main Japanese islands, Kyūshū was occupied by the 24th Infantry Division, with some responsibility for Shikoku. Honshū was occupied by the First Cavalry Division. Hokkaidō was occupied by the 11th Airborne Division.

By June 1950, all of these army units had suffered extensive troop reductions, and their combat effectiveness was seriously weakened. When North Korea invaded South Korea, elements of the 24th Division were flown into South Korea to try to stem the massive invasion force there, but the green occupation troops, while acquitting themselves well when suddenly thrown into combat almost overnight, suffered heavy casualties and were forced into retreat until other Japan occupation troops could be sent to assist.

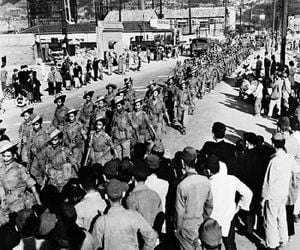

The official British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF), composed of Australian, British, Indian and New Zealand personnel, was deployed on February 21, 1946. While U.S. forces were responsible for overall military government, BCOF was responsible for supervising demilitarization and the disposal of Japan's war industries.[25] BCOF was also responsible for occupation of several western prefectures and had its headquarters at Kure. At its peak, the force numbered about 40,000 personnel. During 1947, BCOF began to decrease its activities in Japan, and it was officially wound up in 1951.[26]

Accomplishments of the Occupation

Disarmament

Japan's postwar constitution, adopted under Allied supervision, included a "Peace Clause" (Article 9), which renounced war and banned Japan from maintaining any armed forces.[27] This was intended to prevent the country from ever becoming an aggressive military power again. However, within a decade, America was pressuring Japan to rebuild its army as a bulwark against Communism in Asia after the Chinese Revolution and the Korean War, and Japan established Self-Defense Forces.[28] Traditionally, Japan's military spending has been restricted to about 1% of its GNP, though this is by popular practice, not law, and has fluctuated up and down from this figure.[28] Recently, past Prime Ministers Junichiro Koizumi and Shinzo Abe, and other politicians have tried to repeal or amend the clause. Although the American Occupation was to demilitarize the Japanese, due to an Asian threat of communism, the Japanese military slowly regained its powerful status. Japan currently has the fourth largest army based on dollar spent on army resources.

Industrial disarmament

In order to further remove Japan as a potential future threat to the U.S. the Far Eastern Commission decided that Japan was to be partly de-industrialized. The necessary dismantling of Japanese industry was foreseen to have been achieved when Japanese standards of living had been reduced to those existing in Japan the period 1930 - 1934 (see Great Depression).[29][30] In the end the adopted program of de-industrialization in Japan was implemented to a lesser degree than the similar U.S. "industrial disarmament" program in Germany (see Industrial plans for Germany).[29]

Liberalization

The Allies attempted to dismantle the Japanese Zaibatsu. However, the Japanese resisted these attempts, claiming that the zaibatsu were required in order for Japan to compete internationally, and looser industrial groupings known as keiretsu evolved.[31] A major land reform was also conducted, led by Wolf Ladejinsky of General Douglas MacArthur's SCAP staff.

- ↑ Takemae Eiji, Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and Its Legacy (New York: Continuum, 2002), 42.

- ↑ Takemae, 46.

- ↑ Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 226.

- ↑ Takemae, 4.

- ↑ Takemae, 5.

- ↑ Takemae, 47.

- ↑ Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), 271ff.

- ↑ Hasegawa 2005, 271ff.

- ↑ National Diet Library, Glossary: Birth of the Constitution of Japan Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ↑ Takemae, 3.

- ↑ "The [Hinomaru] was indispensable for seeing new recruits off to war. On the day the recruit was to leave... neighbors gathered in front of his house, where the Japanese flag was displayed... all shouted banzai for the send-off, waving smaller flags." Roger Goodman and Kirsten Refsing, Ideology and Practice in Modern Japan (London: Routledge, 1992), 33.

- ↑ John W. Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (New York: Norton, 1999), 226.

- ↑ Dower, 1999, 336.

- ↑ Steven R. Weisman, "For Japanese, Flag and Anthem Sometimes Divide," New York Times, April 29, 1990, Online Text Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ↑ Christopher Philip Hood, Japanese Education Reform: Nakasone's Legacy (New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, 2001), 70.

- ↑ D. Cripps, "Flags and Fanfares: The Hirnomaru Flag and the Kimigayo Anthem," in Case Studies on Human Rights in Japan, eds. Roger Goodman and Ian Neary (London: Routledge, 1996), 81.

- ↑ Goodman and Refsing, 33.

- ↑ Takemae, 57.

- ↑ Takemae, 58.

- ↑ Gordon, 228.

- ↑ Takemae, 77-79.

- ↑ Robert Guillain, I saw Tokyo burning: An eyewitness narrative from Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima (London: J. Murray, 1981).

- ↑ Herbert Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan (New York: Harper Perennial, 2001), 571-573.

- ↑ Takemae, 235-238.

- ↑ Australian War Memorial, British Commonwealth Occupation Force 1946–51 Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ↑ Takemae, 131-136.

- ↑ Takemae, 271.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Takemae, 522.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Frederick H. Gareau, "Morgenthau's Plan for Industrial Disarmament in Germany," The Western Political Quarterly 14, no. 2 (June 1961): 531.

- ↑ Note: A footnote in Gareau also states: "For a text of this decision, see Activities of the Far Eastern Commission. Report of the Secretary General, February, 1946 to July 10, 1947, Appendix 30, p. 85."

- ↑ Takemae, 334-335.