Difference between revisions of "Nobel Prize" - New World Encyclopedia

m |

|||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

Although Nobel's will established the prizes, his plan was incomplete and took five years before the Nobel Foundation could be established and the first prizes awarded on December 10, 1901. | Although Nobel's will established the prizes, his plan was incomplete and took five years before the Nobel Foundation could be established and the first prizes awarded on December 10, 1901. | ||

| − | |||

==Prize Categories== | ==Prize Categories== | ||

| − | + | Alfred Nobel's will made provision for only five prizes; the Economics prize was added later in his memory. The six prizes awarded are: | |

| − | Awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to "the person who shall have made the most important discovery or invention within the field of physics". | + | *[[Nobel Prize#Nobel Prize in Physics|Nobel Prize in Physics]] - Awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to "the person who shall have made the most important discovery or invention within the field of physics". |

| − | + | *[[Nobel Prize#Nobel Prize in Chemistry|Nobel Prize in Chemistry]] - Awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to "the person who shall have made the most important chemical discovery or improvement". | |

| − | + | *[[Nobel Prize#Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine|Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine]] - Awarded by the Karolinska Institute to "the person who shall have made the most important discovery within the domain of physiology or medicine". | |

| − | Awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to "the person who shall have made the most important chemical discovery or improvement". | + | *[[Nobel Prize#Nobel Prize in Literature|Nobel Prize in Literature]] - Awarded by the Swedish Academy to "the person who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work of an idealistic tendency". |

| − | + | *[[Nobel Prize#Nobel Prize in Peace|Nobel Prize in Peace]] - Awarded by the Norwegian Nobel Committee to "the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity among nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses". | |

| − | + | *[[Nobel Prize#Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics|Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics]] - Also known as the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, it was instituted in 1969 by Sveriges Riksbank, the Bank of Sweden. Although it is awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences with the official Nobel prizes, it is not paid for by his money, and is technically not a Nobel Prize. | |

| − | Awarded by the Karolinska Institute to "the person who shall have made the most important discovery within the domain of physiology or medicine". | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Awarded by the Swedish Academy to "the person who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work of an idealistic tendency". | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Awarded by the Norwegian Nobel Committee to "the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity among nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses". | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Also known as the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, it was instituted in 1969 by Sveriges Riksbank, the Bank of Sweden. Although it is awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences with the official Nobel prizes, it is not paid for by his money, and is technically not a Nobel Prize. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Nomination and Selection== | ==Nomination and Selection== | ||

| Line 75: | Line 62: | ||

The first Nobel Peace Prize was awarded in 1901, given by the President of Norwegian Parliament until the establishment of the Norwegian Nobel Committee in 1904. Its five members are appointed by the Norwegian Parliament, or the Stortinget, and it is entrusted both with the preparatory work related to prize adjudication and with the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize. Its members are independent and do not answer to lawmakers. Members of the Norwegian government are not allowed to take any part in it. | The first Nobel Peace Prize was awarded in 1901, given by the President of Norwegian Parliament until the establishment of the Norwegian Nobel Committee in 1904. Its five members are appointed by the Norwegian Parliament, or the Stortinget, and it is entrusted both with the preparatory work related to prize adjudication and with the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize. Its members are independent and do not answer to lawmakers. Members of the Norwegian government are not allowed to take any part in it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Nobel Prize in Physics== | ||

| + | [[Image:Hannes-alfven.jpg|thumb|200px|Hannes Alfvén (1908–1995) accepting the Nobel Prize for his work on [[magnetohydrodynamics]] [http://www.agu.org/sci_soc/alfven.html].]] | ||

| + | List of [[Nobel Prize]] laureates in [[Physics]] from [[1901]] to the present day. 178 awards have been given as of 2006. The prize is awarded every year by the [[Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===Controversies=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | {|align="right" border="0" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Nikola Tesla.jpg|thumb|111px|Tesla greatly influenced life in the 20th and 21st century.]] | ||

| + | |[[Image:Thomas Edison.jpg|thumb|111px|Edison applied "mass production" to the invention process.]] | ||

| + | |}<includeonly></includeonly> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Thomas Edison]] and [[Nikola Tesla]] were mentioned as potential laureates in 1915, but it is believed that due to their animosity toward each other neither was ever given the award, despite their enormous scientific contributions. There is some indication that each sought to minimize the other one's achievements and right to win the award; that both refused to ever accept the award if the other received it first; and that both rejected any possibility of sharing it—as was rumoured in the press at the time. <ref> "[http://www.jimloy.com/physics/edison.htm Edison and Tesla Win Nobel Prize in Physics]", Literary Digest, December 18, 1915. </ref><ref>Cheney, Margaret, ''Tesla: Man Out of Time'' , ISBN 0-13-906859-7.</ref><ref>Seifer, Marc J., ''Wizard, the Life and Times of Nikola Tesla'', ISBN 1-559723-29-7 (HC), ISBN 0-806519-60-6 (SC). </ref><ref>O'Neill, John H., ''Prodigal Genius'', ISBN 0-914732-33-1. </ref> Tesla had a greater financial need for the award than Edison: in 1916, he filed for [[bankruptcy]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nikola Tesla did not receive recognition for his work in early radio, much like the case of the poor, little-known Italian mechanical genius, [[Antonio Meucci]] (who was finally recognized, in his case, as the inventor of the telephone by the US Congress in 2002, 113 years after his death); in 1909, [[Guglielmo Marconi]] and [[Karl Ferdinand Braun]] shared the Nobel Prize "in recognition of their contributions to the [[invention of radio|development of wireless telegraphy]]". In 1947, the United States Supreme Court credited Tesla, and not Marconi, as being the inventor of the radio. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Albert Einstein Head.jpg|thumb|right|111px|Albert Einstein, though awarded a 1921 Prize, may have deserved 4 total Nobels.]] | ||

| + | [[Albert Einstein]]'s 1921 Nobel Prize award mainly recognized him for his explanation of the photoelectric effect in 1905 and "for his services to Theoretical Physics"—due to the often counter-intuitive concepts and advanced constructs of his relativity theory, some of which are so far in advance of possible experimental verifications, until only recently (eg. gravitational waves, bending of light, black holes, etc.).<ref>"[http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/09/060914094623.htm General Relativity Survives Gruelling Pulsar Test: Einstein At Least 99.95 Percent Right]", Particle Physics & Astronomy Research Council, September 14, 2006.</ref> His other significant contributions in the [[Annus Mirabilis Papers]], on [[Brownian motion]] and on [[special relativity]], were not explicitly recognized by the Nobel Prize Committee. This may have been because the committee believed [[Henri Poincaré]], who died in 1912, had at least an equal claim as the originator of special relativity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Robert Millikan]] is widely believed to have been denied the [[1920]] prize for physics owing to [[Felix Ehrenhaft]]'s claims to have measured charges smaller than Millikan's [[elementary charge]]. Ehrenhaft's claims were ultimately dismissed and Millikan was awarded the prize in [[1923]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Chung-Yao Chao]], while a graduate student at Caltech in 1930, first captured [[positron]]s through [[electron-positron annihilation]], but did not realize what they were. [[Carl D. Anderson]], who won the 1936 Nobel Physics Prize for his discovery of positron—using the same radioactive source (ThC) as Chao's—acknowledged, late in life, that Chao had inspired his discovery. Much of Anderson's own work was based on Chao's research. Chao died in [[1998]]— without sharing an honor of receiving a Nobel prize acknowledgment [http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~chinaus/publications/Minerva-2004.pdf]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Lise Meitner]] contributed directly to the discovery of [[nuclear fission]] in 1939 but received no Nobel recognition [http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/books/reviews/lisemeitner.htm]. In fact, it was she, not [[Otto Hahn]], who first analysed the accumulated experimental data and figured out fission. In his defense, Hahn was under strong pressure from the Nazis to minimize Meitner's role since she was Jewish. But he maintained this position even after the war. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The 1956 Prize was awarded to Bardeen, Shockley, and Brattain for the discovery of the transistor, because the Nobel committee did not recognize numerous preceding patent applications. As early as 1928, [[Julius Edgar Lilienfeld]] patented several modern transistor types.<ref>"[http://chem.ch.huji.ac.il/~eugeniik/history/lilienfeld.htm Lilienfeld Biodata]".</ref> In 1934, [[Oskar Heil]] patented the field-effect transistor. It is unclear whether either had really built such devices, but they did cause later workers significant patent problems. Further, Herbert F. Mataré and Heinrich Walker, at Westinghouse Paris, applied for a patent in 1948 on an amplifier based on the minority carrier injection process. Mataré had first observed transconductance effects during the manufacture of germanium duodiodes for German radar equipment during WW2. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Chien-Shiung Wu]] (nicknamed the "First Lady of Physics") disproved the law of the [[Parity (physics)|conservation of parity]] (1956) and was the first [[Wolf Prize]] winner in physics. She died in [[1997]] without receiving the Nobel [http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~chinaus/publications/Minerva-2004.pdf]. Wu assisted [[Tsung-Dao Lee]] personally in his parity laws development—with [[Chen Ning Yang]]—by providing him with a possible test method for beta decay in 1956 that worked successfully. Some consider this very instrumental in the creation of the laws, but she did not share their Nobel Prize—a fact widely blamed on sexism on the part of the selection committee. Her book Beta Decay (1965) is still a sine qua non reference for nuclear physicists. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The sole award to [[Lev Landau]] of the 1962 Nobel Prize—for his work on the theory of liquid helium—bypassed recognition mainly due [[Richard Feynman]]'s seminal work (1953-58) on the [[superfluid]] behaviour of [[liquid helium]], which was the first successful solved model for the explanation of the phenomenon of superfluidity. Feynman's work incorporated, for the first time, [[Feynman diagrams]]<ref>"[http://www.physicstoday.org/pt/vol-54/iss-5/p87.html Renormalized Relations in Condensed Matter]", Physics Online Letters.</ref> and a [[path integral formulation]], now indispensible tools-of-the-trade in condensed matter physics. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Nobel Committee neglected the equal contributions of Israeli physicist [[Yuval Ne'eman]] in its 1969 Nobel Prize Award to [[Murray Gell-Mann]] solely—for his work on the classification of elementary particles and their weak interactions. In 1961, while working at the University of London, Ne'eman independently worked out—using simple [[Lie group]] ideas—the same [[Eightfold way (physics)|Eightfold Way]] of [[hadrons]] arrangement, by grouping particles in octets, in accordance with their properties (e.g., charges, mass): the essential [[quark]] model. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1964, [[George Zweig]], then a PhD student at Caltech, boldy espoused the real physical existence of ''aces''—possessing several pretty unorthodox attributes (essentially Gell-Mann's ''quarks'', though regarded by the latter then as just mere theoretical shorthand construct)—at a time which is very 'anti-quark', in the confused late '60s: at great cost to himself and career path, as he suffered the obfuscating ostracism and wrath from the then-scientific 'mainstream orthodoxy', as it turned out. Despite the awardings of the 1969 Prize for contributions in the classification of elementary particles, coupled with the 1990 Prize for the development and proof of the quark model: Zweig's contributions have largely not been recognized. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[1974]] prize was awarded to [[Martin Ryle]] and [[Antony Hewish]]'s pioneering research in radioastrophysics; Hewish was recognized for his decisive role in the discovery of [[pulsar]]s. [[Jocelyn Bell]], Hewish's graduate student, was not recognized, although she was the first to notice the stellar radio source which was later recognised as a pulsar.<ref name="Sharon">Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, ''Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles and Momentous Discoveries''.</ref>While the astronomer [[Fred Hoyle]] argued that Bell should have been included in the Prize, Bell herself countered that graduate students don't win Nobel prizes—[[Louis-Victor de Broglie]], [[Douglas Osheroff]], [[Gerard 't Hooft]] and [[H. David Politzer]] are exceptions to this seeming maxim. ''Incidentally, another interesting, contrasting case occurred in 1978: the Nobel Physics Prize winners [[Arno Allan Penzias]] and [[Robert Woodrow Wilson]] of 1978—awarded for the chanced "detection of [[Cosmic microwave background radiation]]"—themselves initially did not comprehend the "implications and the working out of the meanings behind" their findings, and similarly had to have their discovery elucidated to them.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Fred Hoyle]] was denied a share of the [[Nobel Prize In Physics]] in [[1983]], although the winner [[William Fowler]] acknowledged Hoyle as the pioneer of the concept of [[stellar nucleosynthesis]] (1946). It is possible that the somewhat unconventional grain that runs through and characterizes many of Fred Hoyle's controversial dissensions and critiquing, as well as his posited 'scientific' theories (e.g. anti-chemical evolution and cosmological steady state theories)—coupled with his criticism of the Nobel committee with respect to omitting Jocelyn Bell, was the contribution for this. Hoyle's obituary in ''Physics Today'' [http://www.physicstoday.org/pt/vol-54/iss-11/p75b.html] notes that " Many of us felt that Hoyle should have shared Fowler's 1983 Nobel Prize in Physics, but the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences later made partial amends by awarding Hoyle, with Edwin Salpeter, its 1997 Crafoord Prize ". | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Nobel Prize in Chemistry== | ||

| + | The Chemistry prize is awarded every year by the [[Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Controversies=== | ||

| + | [[Dmitri Mendeleev]], who originated the [[periodic table]] of the [[chemical element|elements]], never received a prize. He died in [[1907]], six years after the first Nobel Prizes were awarded. He came within one vote of winning the prize in 1906, but died the next year. [http://www.brightsurf.com/item/019850912X/The_Road_to_Stockholm_Nobel_Prizes_Science_and_Scientists.html] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine== | ||

| + | The prize in [[Physiology]] or [[Medicine]] has been awarded every year since 1901. The most famous award was in 1962, given to |[[Francis Harry Compton Crick]], [[James Dewey Watson]], [[Maurice Wilkins|Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins]] "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of [[nucleic acid]]s and its significance for information transfer in living material"<ref>[http://nobelprize.org/medicine/laureates/1962/index.html The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1962].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===Controversies=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Banting and Best.jpg|thumb|right|111px|Sir Frederick Banting (right) was awarded a Nobel for the discovery of insulin but his parter Charles Best (left) was not]] | ||

| + | [[Charles Best]] first isolated [[insulin]], but was excluded from the Nobel Prize in favour of his associate [[John James Richard Macleod|John Macleod]]. This snub so incensed Best's colleague, [[Frederick Banting]], that he later voluntarily shared half of his [[1923]] Nobel Prize award money with Best. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Oswald Theodore Avery]], best known for his 1944 discovery that [[DNA]] is the material of which [[genes]] and [[chromosomes]] are composed, never did receive any Nobel Prize, although two Nobel Laureates [[Joshua Lederberg]] and [[Arne Tiselius]] unfailingly praised him and his work: as serving as a pioneering platform for further genetic research and advance. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The 1952 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine awarded solely to [[Selman Waksman]] for his discovery of [[streptomycin]] had omitted recognition due his co-discoverer [[Albert Schatz]].<ref name="Wainwright">Wainwright, Milton ''"A Response to William Kingston, "Streptomycin, Schatz versus Waksman, and the balance of Credit for Discovery""'', Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences - Volume 60, Number 2, April 2005, pp. 218-220, Oxford University Press.</ref> There was a litigation brought by Schatz against Waksman over the details and credit of streptomycin's discovery. The litigation result: Schatz was awarded a substantial settlement, and, Waksman and Schatz would be officially considered co-discoverers of streptomycin. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Jonas Salk]] and [[Albert Sabin]], who discovered, respectively, the injected and oral vaccines for [[polio]], never received Nobel Prizes even though their discoveries enabled humankind to conquer a dreaded disease, and, lives of thousands of people had been saved since the late fifties. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Heinrich J. Matthaei]] broke the [[genetic code]] in 1961 with [[Marshall Warren Nirenberg]] in their poly-U experiment at NIH in Bethesda, Maryland, paving the way for modern [[genetics]]; but though Nirenberg became a Nobel Laureate in 1968, Matthaei, who was responsible for experimentally obtaining the first codon (genetic code), somehow did not get to win his deserving share of the Nobel prize.<ref name="Judson">[[Horace Freeland Judson]], ''The Great Betrayal: Fraud in Science'', 1st. Ed., 2004.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The 1962 Prize awarded to [[James D. Watson]], [[Francis Crick]] and [[Maurice Wilkins]] for their discovery of the [[structure of DNA]] does not recognize other major contributions. In particular, the work of [[Rosalind Franklin]] has not been given a single officially cited credit, and there is [[King's College (London) DNA Controversy|further controversy]] over the behaviour and actual extent of the contribution from her former colleague and collaborator Wilkins.<ref name="Maddox">Brenda Maddox, ''Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA'', 2002, ISBN 0-06-018407-8.</ref> Also the biochemist [[Erwin Chargaff]], who discovered [[Chargaff's rules]]—which helped speed up the discovery of the double helical structure of DNA—could have been expected to share the Prize. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The 1975 Prize was awarded to [[David Baltimore]], [[Renato Dulbecco]] and [[Howard Martin Temin]] "for describing how tumor viruses act on the genetic material of the cell". It had been pointed out, though, in this award: Renato Dulbecco was distantly—if at all—involved in the discovery work.<ref name="Judson"/> This award did not recognize the significant contributions of Satoshi Mizutani, Temin's Japanese postdoctoral fellow.<ref name="Weiss">Weiss R.A., ''Viral RNA-dependent DNA polymerase in virions of Rous sarcoma virus'', Reviews in Medical Virology, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 3-11(9), Jan/Mar 1998.</ref> Mizutani and Temin jointly discovered that the [[Rous sarcoma virus]] particle contained the [[enzyme]] [[reverse transcriptase]]; Mizutani was responsible for the significant experiment confirming Temin's ''[[provirus]] hypothesis''.<ref name="Judson"/> | ||

==Nobel Prize in Literature== | ==Nobel Prize in Literature== | ||

| Line 98: | Line 151: | ||

TV and radio personality Gert Fylking started the tradition of shouting 'Äntligen!', Swedish for 'At last!', at the announcing of the award winner, as a protest to the academies constant nomination of "authors more or less unknown to the general public". Fylking later agreed to stop his outburst, though the tradition has been carried on by others. | TV and radio personality Gert Fylking started the tradition of shouting 'Äntligen!', Swedish for 'At last!', at the announcing of the award winner, as a protest to the academies constant nomination of "authors more or less unknown to the general public". Fylking later agreed to stop his outburst, though the tradition has been carried on by others. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Nobel Prize in Peace== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

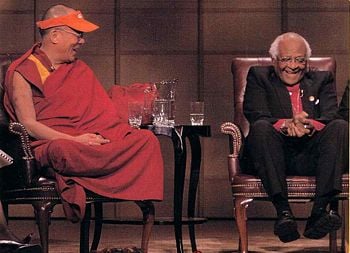

[[Image:Dalai Lama & Bishop Tutu. Carey Linde.jpg|right|thumb|350px|Nobel Peace Prize Winners the [[Dalai Lama]] & [[Desmond Tutu|Bishop Tutu]]. [[Vancouver]], [[Canada]], 2004. Photo by Carey Linde]] | [[Image:Dalai Lama & Bishop Tutu. Carey Linde.jpg|right|thumb|350px|Nobel Peace Prize Winners the [[Dalai Lama]] & [[Desmond Tutu|Bishop Tutu]]. [[Vancouver]], [[Canada]], 2004. Photo by Carey Linde]] | ||

According to Alfred Nobel's will, the Peace Prize should be awarded "to the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between the nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses". | According to Alfred Nobel's will, the Peace Prize should be awarded "to the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between the nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses". | ||

| Line 129: | Line 174: | ||

On closer inspection, the peace-laureates often have a lifetime's history of working at and promoting humanitarian issues, as in the examples of German medic Albert Schweitzer (1952 laureate), civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (1964 laureate); Catholic missionary Mother Teresa; and Aung San Suu Kyi, a Buddhist nonviolent pro-democracy activist (1991 laureate). Still others are selected for tireless efforts, as in the examples of Jimmy Carter and Mohamed ElBaradei. Others, even today, are quite controversial, due to the recipient's political activity, as in the case of Henry Kissinger (1973 laureate), Mikhail Gorbachev (1990 laureate) or Yasser Arafat (1994 laureate) whose Fatah movement began, and still serves, as a terrorist organization. Finally, the Peace Prize draws criticism for candidates whom it overlooks, such as Mahatma Gandhi, Pope John XXIII, Steve Biko, Hélder Câmara, Raphael Lemkin and Oscar Romero. | On closer inspection, the peace-laureates often have a lifetime's history of working at and promoting humanitarian issues, as in the examples of German medic Albert Schweitzer (1952 laureate), civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (1964 laureate); Catholic missionary Mother Teresa; and Aung San Suu Kyi, a Buddhist nonviolent pro-democracy activist (1991 laureate). Still others are selected for tireless efforts, as in the examples of Jimmy Carter and Mohamed ElBaradei. Others, even today, are quite controversial, due to the recipient's political activity, as in the case of Henry Kissinger (1973 laureate), Mikhail Gorbachev (1990 laureate) or Yasser Arafat (1994 laureate) whose Fatah movement began, and still serves, as a terrorist organization. Finally, the Peace Prize draws criticism for candidates whom it overlooks, such as Mahatma Gandhi, Pope John XXIII, Steve Biko, Hélder Câmara, Raphael Lemkin and Oscar Romero. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Mohandas Gandhi resized for biography.jpg|thumb|111px|Gandhi was nominated five times but never won.]] | ||

| + | [[Mahatma Gandhi]] never received the Nobel Peace Prize, though he was nominated for it five times between 1937 and 1948. Einstein commented "Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this (Gandhi) ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth.". [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]] was also known to have been inspired by Gandhi's example and espousal of non-violence resistance movement in the independence struggle of India: Gandhi had also been known, though, to make—at times shocking, at times controversial—life's statements and personal philosophy bordering on extreme idealism and racial judgments. Decades later, though, the Nobel Committee publicly declared its regret for the omission. The Nobel Committee may have tacitly acknowledged its error, however, when in 1948 (the year of Gandhi's death), it made no award, stating "there was no suitable living candidate". Similarly, when the [[Tenzin Gyatso, 14th Dalai Lama|Dalai Lama]] was awarded the Peace Prize in 1989, the chairman of the committee said that this was "in part a tribute to the memory of Mahatma Gandhi". The official Nobel e-museum has an [http://nobelprize.org/peace/articles/gandhi/index.html article] discussing the issue. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics== | ||

| + | The Nobel Prize in Economics is a prize awarded each year for outstanding intellectual contributions in the field of economics. The award was instituted by the Bank of Sweden, the world's oldest central bank, at its 300th anniversary in 1968. Although it was not one of the awards established in the will of Alfred Nobel, economics laureates receive their diploma and gold medal from the Swedish monarch at the same December 10 Stockholm ceremony as the other Nobel laureates. The amount of money awarded to the economics laureates is also equal to that of the other prizes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The prestige of the prize derives in part from its association with the awards created by Alfred Nobel's will, an association which has often been a source of controversy. The prize is commonly referred to as the Nobel Prize in Economics or, more correctly, as the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In February 1995, it was decided that the economics prize be essentially defined as a prize in social sciences, opening the Nobel Prize to great contributions in fields like political science, psychology, and sociology. The Economics Prize Committee has also undergone changes to require two non-economists to decide the prize each year, whereas previously the prize committee had consisted of five economists. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The economics laureates, like the Nobel laureates in chemistry and physics, are chosen by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Nominations of about one hundred living persons are made each year by qualified nominators and are received by a five to eight member committee, which then submits its choice of winners to the Nobel Assembly for its final approval. As with the other prizes, no more than three people can share the prize for a given year and they must be living at the time the prize is awarded. The final award is made in Stockholm and is accompanied by a sum of money. | ||

==Criticisms of the Nobel Prizes== | ==Criticisms of the Nobel Prizes== | ||

| Line 146: | Line 203: | ||

In 2001, the government of Norway began awarding the Abel Prize, specifically with the intention of being a substitute for the missing mathematics Nobel. Beginning in 2004, the Shaw Prize, which resembles the Nobel Prize, included an award in mathematical sciences. The Fields Medal is often described as the "Nobel Prize of mathematics", but the comparison is not very apt because the Fields is limited to mathematicians not over forty years old. | In 2001, the government of Norway began awarding the Abel Prize, specifically with the intention of being a substitute for the missing mathematics Nobel. Beginning in 2004, the Shaw Prize, which resembles the Nobel Prize, included an award in mathematical sciences. The Fields Medal is often described as the "Nobel Prize of mathematics", but the comparison is not very apt because the Fields is limited to mathematicians not over forty years old. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Recipients who did not receive their award in person=== | ||

| + | [[Carl von Ossietzky]], the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize winner—was at first required by the Nazi government to decline the Nobel Prize, a demand that Ossietzky did not honor, and then was practically 'prevented' by the same government from going to Olso personally to accept the Nobel Prize (kept under surveillance actually—a virtual 'house arrest'—in a civilian hospital until his demise in 1938), though the German Propaganda Ministry was known to have publicly declared Ossietzky's total freedom to go to Norway to accept the award. After this incident—in 1937—the German government decreed that in the future no German could accept any Nobel Prize. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Andrei Sakharov]], the first Soviet Citizen to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, in 1975, was not allowed to receive or personally travel to Oslo to accept the prize. He was described as "a Judas" and a "laboratory rat of the West" by the Soviet authorities. His wife, [[Elena Bonner]], who was in Italy for medical treatment, received the prize in her husband's stead and presented the Nobel Prize acceptance speech by proxy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Aung San Suu Kyi]] was awarded the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize but was not allowed to make any formal acceptance speech or statement of any kind to that effect, nor leave Myanmar (Burma) to receive the Prize. Her sons Alexander and Kim accepted the Nobel Peace Prize on her behalf. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Elfriede Jelinek]] was awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize in Literature but declined to go in person to Stockholm to receive the Prize, citing severe social phobia and mental illness. She made a video instead and wrote out the speech text to be read out in lieu. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Harold Pinter]] was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2005, but was unable to attend the ceremonies owing to poor health. He, too, delivered his controversial, 'all-defying' speech via video. | ||

| + | |||

==Repeat Recipients== | ==Repeat Recipients== | ||

| Line 192: | Line 261: | ||

*Public Broadcasting Service. The Prize: Controversy and Landmarks. Retrieved on July 30, 2006. | *Public Broadcasting Service. The Prize: Controversy and Landmarks. Retrieved on July 30, 2006. | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Credit5|Nobel_Prize|72961458|Nobel_Prize_in_Literature|79297840|Nobel_Prize_in_Economics|79200890|Nobel_Peace_Prize|79260609|Nobel_Prize_controversies|84847848|}} |

Revision as of 18:25, 31 October 2006

The Nobel Prizes are prizes instituted by the Will law of Alfred Nobel, awarded to people, and some organizations, who have done outstanding research, invented groundbreaking techniques or equipment, or made outstanding contributions to society. The Nobel Prizes, which are generally awarded annually in the categories of physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature, peace and economics, are widely regarded as the supreme commendation in the world today.

As of November 2005, a total of 776 Nobel Prizes have been awarded. 758 of the prizes awarded to individuals and 18 to organizations, though a few prize winners have declined the award. There are years in which one or more prizes are not awarded; however, the prizes must be awarded at least once every five years. During World War II no prizes were awarded in any category from 1940 through 1942. The selection of the peace prize in particular was greatly hampered by Nazi Germany's occupation of Norway. The prize cannot be revoked and nominees must be living at the time of their nomination. Since 1974, the award cannot be given out posthumously.

Nobel's Will

The prizes were instituted by the final will of Alfred Nobel, a Swedish chemist, industrialist, and the inventor of dynamite. Alfred Nobel wrote several wills during his lifetime, the last one written on November 27, 1895, more than a year before he died. He signed it at the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris on November 27, 1895. Nobel's work had directly involved the creation of explosives, and he became increasingly uneasy with the military usage of his inventions. It is said that this was motivated in part by his reading of a premature obituary of himself, published in error by a French newspaper on the occasion of the death of Nobel's brother Ludvig, and which condemned Alfred as a "merchant of death." After his death, Alfred left 94% of his worth to the establishment of five prizes:

The whole of my remaining realizable estate shall be dealt with in the following way:

The capital shall be invested by my executors in safe securities and shall constitute a fund, the interest on which shall be annually distributed in the form of prizes to those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind. The said interest shall be divided into five equal parts, which shall be apportioned as follows: one part to the person who shall have made the most important discovery or invention within the field of physics; one part to the person who shall have made the most important chemical discovery or improvement; one part to the person who shall have made the most important discovery within the domain of physiology or medicine; one part to the person who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work of an idealistic tendency; and one part to the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity among nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.

The prizes for physics and chemistry shall be awarded by the Swedish Academy of Sciences; that for physiological or medical works by the Caroline Institute in Stockholm; that for literature by the Academy in Stockholm; and that for champions of peace by a committee of five persons to be elected by the Norwegian Storting. It is my express wish that in awarding the prizes no consideration whatever shall be given to the nationality of the candidates, so that the most worthy shall receive the prize, whether he be a Scandinavian or not.

Although Nobel's will established the prizes, his plan was incomplete and took five years before the Nobel Foundation could be established and the first prizes awarded on December 10, 1901.

Prize Categories

Alfred Nobel's will made provision for only five prizes; the Economics prize was added later in his memory. The six prizes awarded are:

- Nobel Prize in Physics - Awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to "the person who shall have made the most important discovery or invention within the field of physics".

- Nobel Prize in Chemistry - Awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to "the person who shall have made the most important chemical discovery or improvement".

- Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine - Awarded by the Karolinska Institute to "the person who shall have made the most important discovery within the domain of physiology or medicine".

- Nobel Prize in Literature - Awarded by the Swedish Academy to "the person who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work of an idealistic tendency".

- Nobel Prize in Peace - Awarded by the Norwegian Nobel Committee to "the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity among nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses".

- Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics - Also known as the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, it was instituted in 1969 by Sveriges Riksbank, the Bank of Sweden. Although it is awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences with the official Nobel prizes, it is not paid for by his money, and is technically not a Nobel Prize.

Nomination and Selection

As compared with some other prizes, the Nobel prize nomination and selection process is long and rigorous. This is an important reason why the Prizes have grown in importance and prestige over the years to become the most important prizes in their field.

Forms, which amount to a personal and exclusive invitation, are sent to about 3000 selected individuals to invite them to submit nominations. In the case of the Nobel Peace Prize, the Nobel Foundation states that nominees may include:

- Members of National Assemblies and Governments of States

- Members of International Courts

- University Rectors

- Professors of Social Sciences, History, Philosophy, Law and Theology

- Directors of Peace Research Institutes and Foreign Policy Institutes

- Persons who have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

- Board Members of Organisations who have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

- Active and Former Members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee

- Former Advisers Appointed by the Norwegian Nobel Institute

Similar nominee requirements are in place for the remaining prizes. The strictly enforced submission deadline for nominations is January 31. Self-nominations are automatically disqualified and only living persons are eligible for the Nobel Prize. Unlike many other awards, the Nobel Prize nominees are never publicly announced, and they are not supposed to be told that they were ever considered for the prize. These records are sealed for 50 years.

After the nomination deadline, a committee compiles and reduces the amount of nominations to a list of 200 preliminary candidates. The list is sent to selected experts in the field of each nominee's work and the list is further shortened to around 15 final candidates. The Committee then writes a report with recommendations and sends it to the Academy or other corresponding institution, depending on the category of the prize. As an example of institute size, the Assembly for the Prize for Medicine has 50 members. The members of the institution then vote to select the winner.

This process varies slightly between the different disciplines. Though literature is rarely awarded to a collaborative group, other prizes often involve multiple awardees.

Posthumous nominations for the Prize have been disallowed since 1974. This has sometimes sparked criticism that people deserving of a Nobel Prize did not receive the award because they died before being nominated. In two cases the Prize has been awarded posthumously to people who were nominated when they were still alive. This was the case with UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld (1961, Peace Prize) and Erik Axel Karlfeldt (1931, Literature); both of whom were awarded the prize in the years they died. William Vickrey (1996, Economics) died before he could receive the prize, but after it was announced.

Awarding Ceremonies

The committees and institutions that serve as selection boards for the prizes typically announce the names of the laureates in October. The prizes are awarded at formal ceremonies held annually on December 10, the anniversary of Alfred Nobel's death.

The first peace prize ceremonies were held at the Norwegian Nobel Institute from 1905 until 1946, later relocated to the Aula of the University of Oslo. In 1990 the award ceremony was held at the Oslo City Hall and as of 2005 the prize was awarded at the Stockholm Concert Hall.

Each award can be given to a maximum of three recipients per year. Each prize constitutes a gold medal, a diploma, and a sum of money. The monetary award is currently about 10 million Swedish Kronor, which is slightly more than one million Euros or about 1.3 million US dollars. This was originally intended to allow laureates to continue working or researching without the pressures of raising money. In actual fact, many prize winners have retired before winning. If there are two winners in one category, the award money is split equally between them. If there are three winners, the awarding committee has the option of splitting the prize money equally among all three, or awarding half of the prize money to one recipient and one-quarter to each of the other recipients. It is common for the winners to donate the prize money to benefit scientific, cultural or humanitarian causes.

Since 1902, the King of Sweden has formally awarded all the prizes, except the Nobel Peace Prize, in Stockholm. King Oscar II of Sweden initially disapproved of awarding grand national prizes to foreigners, but changed his mind after realizing the publicity value of the prizes for the country.

The first Nobel Peace Prize was awarded in 1901, given by the President of Norwegian Parliament until the establishment of the Norwegian Nobel Committee in 1904. Its five members are appointed by the Norwegian Parliament, or the Stortinget, and it is entrusted both with the preparatory work related to prize adjudication and with the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize. Its members are independent and do not answer to lawmakers. Members of the Norwegian government are not allowed to take any part in it.

Nobel Prize in Physics

List of Nobel Prize laureates in Physics from 1901 to the present day. 178 awards have been given as of 2006. The prize is awarded every year by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Controversies

Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla were mentioned as potential laureates in 1915, but it is believed that due to their animosity toward each other neither was ever given the award, despite their enormous scientific contributions. There is some indication that each sought to minimize the other one's achievements and right to win the award; that both refused to ever accept the award if the other received it first; and that both rejected any possibility of sharing it—as was rumoured in the press at the time. [1][2][3][4] Tesla had a greater financial need for the award than Edison: in 1916, he filed for bankruptcy.

Nikola Tesla did not receive recognition for his work in early radio, much like the case of the poor, little-known Italian mechanical genius, Antonio Meucci (who was finally recognized, in his case, as the inventor of the telephone by the US Congress in 2002, 113 years after his death); in 1909, Guglielmo Marconi and Karl Ferdinand Braun shared the Nobel Prize "in recognition of their contributions to the development of wireless telegraphy". In 1947, the United States Supreme Court credited Tesla, and not Marconi, as being the inventor of the radio.

Albert Einstein's 1921 Nobel Prize award mainly recognized him for his explanation of the photoelectric effect in 1905 and "for his services to Theoretical Physics"—due to the often counter-intuitive concepts and advanced constructs of his relativity theory, some of which are so far in advance of possible experimental verifications, until only recently (eg. gravitational waves, bending of light, black holes, etc.).[5] His other significant contributions in the Annus Mirabilis Papers, on Brownian motion and on special relativity, were not explicitly recognized by the Nobel Prize Committee. This may have been because the committee believed Henri Poincaré, who died in 1912, had at least an equal claim as the originator of special relativity.

Robert Millikan is widely believed to have been denied the 1920 prize for physics owing to Felix Ehrenhaft's claims to have measured charges smaller than Millikan's elementary charge. Ehrenhaft's claims were ultimately dismissed and Millikan was awarded the prize in 1923.

Chung-Yao Chao, while a graduate student at Caltech in 1930, first captured positrons through electron-positron annihilation, but did not realize what they were. Carl D. Anderson, who won the 1936 Nobel Physics Prize for his discovery of positron—using the same radioactive source (ThC) as Chao's—acknowledged, late in life, that Chao had inspired his discovery. Much of Anderson's own work was based on Chao's research. Chao died in 1998— without sharing an honor of receiving a Nobel prize acknowledgment [2].

Lise Meitner contributed directly to the discovery of nuclear fission in 1939 but received no Nobel recognition [3]. In fact, it was she, not Otto Hahn, who first analysed the accumulated experimental data and figured out fission. In his defense, Hahn was under strong pressure from the Nazis to minimize Meitner's role since she was Jewish. But he maintained this position even after the war.

The 1956 Prize was awarded to Bardeen, Shockley, and Brattain for the discovery of the transistor, because the Nobel committee did not recognize numerous preceding patent applications. As early as 1928, Julius Edgar Lilienfeld patented several modern transistor types.[6] In 1934, Oskar Heil patented the field-effect transistor. It is unclear whether either had really built such devices, but they did cause later workers significant patent problems. Further, Herbert F. Mataré and Heinrich Walker, at Westinghouse Paris, applied for a patent in 1948 on an amplifier based on the minority carrier injection process. Mataré had first observed transconductance effects during the manufacture of germanium duodiodes for German radar equipment during WW2.

Chien-Shiung Wu (nicknamed the "First Lady of Physics") disproved the law of the conservation of parity (1956) and was the first Wolf Prize winner in physics. She died in 1997 without receiving the Nobel [4]. Wu assisted Tsung-Dao Lee personally in his parity laws development—with Chen Ning Yang—by providing him with a possible test method for beta decay in 1956 that worked successfully. Some consider this very instrumental in the creation of the laws, but she did not share their Nobel Prize—a fact widely blamed on sexism on the part of the selection committee. Her book Beta Decay (1965) is still a sine qua non reference for nuclear physicists.

The sole award to Lev Landau of the 1962 Nobel Prize—for his work on the theory of liquid helium—bypassed recognition mainly due Richard Feynman's seminal work (1953-58) on the superfluid behaviour of liquid helium, which was the first successful solved model for the explanation of the phenomenon of superfluidity. Feynman's work incorporated, for the first time, Feynman diagrams[7] and a path integral formulation, now indispensible tools-of-the-trade in condensed matter physics.

The Nobel Committee neglected the equal contributions of Israeli physicist Yuval Ne'eman in its 1969 Nobel Prize Award to Murray Gell-Mann solely—for his work on the classification of elementary particles and their weak interactions. In 1961, while working at the University of London, Ne'eman independently worked out—using simple Lie group ideas—the same Eightfold Way of hadrons arrangement, by grouping particles in octets, in accordance with their properties (e.g., charges, mass): the essential quark model.

In 1964, George Zweig, then a PhD student at Caltech, boldy espoused the real physical existence of aces—possessing several pretty unorthodox attributes (essentially Gell-Mann's quarks, though regarded by the latter then as just mere theoretical shorthand construct)—at a time which is very 'anti-quark', in the confused late '60s: at great cost to himself and career path, as he suffered the obfuscating ostracism and wrath from the then-scientific 'mainstream orthodoxy', as it turned out. Despite the awardings of the 1969 Prize for contributions in the classification of elementary particles, coupled with the 1990 Prize for the development and proof of the quark model: Zweig's contributions have largely not been recognized.

The 1974 prize was awarded to Martin Ryle and Antony Hewish's pioneering research in radioastrophysics; Hewish was recognized for his decisive role in the discovery of pulsars. Jocelyn Bell, Hewish's graduate student, was not recognized, although she was the first to notice the stellar radio source which was later recognised as a pulsar.[8]While the astronomer Fred Hoyle argued that Bell should have been included in the Prize, Bell herself countered that graduate students don't win Nobel prizes—Louis-Victor de Broglie, Douglas Osheroff, Gerard 't Hooft and H. David Politzer are exceptions to this seeming maxim. Incidentally, another interesting, contrasting case occurred in 1978: the Nobel Physics Prize winners Arno Allan Penzias and Robert Woodrow Wilson of 1978—awarded for the chanced "detection of Cosmic microwave background radiation"—themselves initially did not comprehend the "implications and the working out of the meanings behind" their findings, and similarly had to have their discovery elucidated to them.

Fred Hoyle was denied a share of the Nobel Prize In Physics in 1983, although the winner William Fowler acknowledged Hoyle as the pioneer of the concept of stellar nucleosynthesis (1946). It is possible that the somewhat unconventional grain that runs through and characterizes many of Fred Hoyle's controversial dissensions and critiquing, as well as his posited 'scientific' theories (e.g. anti-chemical evolution and cosmological steady state theories)—coupled with his criticism of the Nobel committee with respect to omitting Jocelyn Bell, was the contribution for this. Hoyle's obituary in Physics Today [5] notes that " Many of us felt that Hoyle should have shared Fowler's 1983 Nobel Prize in Physics, but the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences later made partial amends by awarding Hoyle, with Edwin Salpeter, its 1997 Crafoord Prize ".

Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Chemistry prize is awarded every year by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Controversies

Dmitri Mendeleev, who originated the periodic table of the elements, never received a prize. He died in 1907, six years after the first Nobel Prizes were awarded. He came within one vote of winning the prize in 1906, but died the next year. [6]

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The prize in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded every year since 1901. The most famous award was in 1962, given to |Francis Harry Compton Crick, James Dewey Watson, Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material"[9]

Controversies

Charles Best first isolated insulin, but was excluded from the Nobel Prize in favour of his associate John Macleod. This snub so incensed Best's colleague, Frederick Banting, that he later voluntarily shared half of his 1923 Nobel Prize award money with Best.

Oswald Theodore Avery, best known for his 1944 discovery that DNA is the material of which genes and chromosomes are composed, never did receive any Nobel Prize, although two Nobel Laureates Joshua Lederberg and Arne Tiselius unfailingly praised him and his work: as serving as a pioneering platform for further genetic research and advance.

The 1952 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine awarded solely to Selman Waksman for his discovery of streptomycin had omitted recognition due his co-discoverer Albert Schatz.[10] There was a litigation brought by Schatz against Waksman over the details and credit of streptomycin's discovery. The litigation result: Schatz was awarded a substantial settlement, and, Waksman and Schatz would be officially considered co-discoverers of streptomycin.

Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin, who discovered, respectively, the injected and oral vaccines for polio, never received Nobel Prizes even though their discoveries enabled humankind to conquer a dreaded disease, and, lives of thousands of people had been saved since the late fifties.

Heinrich J. Matthaei broke the genetic code in 1961 with Marshall Warren Nirenberg in their poly-U experiment at NIH in Bethesda, Maryland, paving the way for modern genetics; but though Nirenberg became a Nobel Laureate in 1968, Matthaei, who was responsible for experimentally obtaining the first codon (genetic code), somehow did not get to win his deserving share of the Nobel prize.[11]

The 1962 Prize awarded to James D. Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins for their discovery of the structure of DNA does not recognize other major contributions. In particular, the work of Rosalind Franklin has not been given a single officially cited credit, and there is further controversy over the behaviour and actual extent of the contribution from her former colleague and collaborator Wilkins.[12] Also the biochemist Erwin Chargaff, who discovered Chargaff's rules—which helped speed up the discovery of the double helical structure of DNA—could have been expected to share the Prize.

The 1975 Prize was awarded to David Baltimore, Renato Dulbecco and Howard Martin Temin "for describing how tumor viruses act on the genetic material of the cell". It had been pointed out, though, in this award: Renato Dulbecco was distantly—if at all—involved in the discovery work.[11] This award did not recognize the significant contributions of Satoshi Mizutani, Temin's Japanese postdoctoral fellow.[13] Mizutani and Temin jointly discovered that the Rous sarcoma virus particle contained the enzyme reverse transcriptase; Mizutani was responsible for the significant experiment confirming Temin's provirus hypothesis.[11]

Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature is awarded annually to an author from any country who has, in the words of Alfred Nobel, produced "the most outstanding work of an idealistic tendency". The work in this case generally refers to an author's collection as a whole, not to any individual work, though individual works are sometimes cited in the awards. The Swedish Academy decides who, if anyone, will receive the prize in any given year and announces the name of the chosen laureate in early October.

The original citation of this Nobel Prize has led to much controversy. In the original Swedish translation, the word idealisk can mean either "idealistic" or "ideal". In earlier years the Nobel Committee stuck closely to the intent of the will, and left out certain world-renowned writers such as Leo Tolstoy and Henrik Ibsen for the Prize because their works were not deemed "idealistic" enough. In later years the wording has been interpreted more liberally, and the Prize has been awarded for lasting literary merit. The choice of the Academy can still generate controversy, particularly for the selection of lesser-known writers or for writers working in avant garde forms such as Dario Fo in 1997 and Elfriede Jelinek in 2004. Critics of the prize point out that many prominent writers have failed to be cited or even nominated for the award.

Each year the Swedish Academy sends out requests for nominations of candidates for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Members of the Academy, members of literature academies and societies, professors of literature and language, former Nobel literature laureates, and the presidents of writers' organizations are all allowed to nominate a candidate.

The prize money of the Nobel Prize has fluctuated since its inauguration but at present stands at 10 million Swedish krona. The winner also wins a gold medal and a Nobel diploma.

The oldest person to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature was Theodor Mommsen, who was 85 when he received the Prize in 1902. The youngest was Rudyard Kipling, who was 42 when he won the Prize in 1907.

Controversies

This history of the Nobel Prize in Literature has been marked in controversy. During World War I and its immediate aftermath, the Nobel committee was criticized for adopting a policy of neutrality, and favored writers from non-combatant countries.

In 1974 Graham Greene, Vladimir Nabokov, and Saul Bellow were considered for the award but passed over for a joint award to Swedish authors, Eyvind Johnson and Harry Martinson, both Nobel judges themselves. Bellow would win the prize in 1976; neither Greene nor Nabokov were honored.

The award to Dario Fo in 1997 was initially considered "rather lightweight" by some critics, as he was seen primarily as a performer and had previously been censured by the Roman Catholic Church. According to Fo's London publisher, Salman Rushdie and Arthur Miller were favorites to win that year, but the organizers stated that the authors would have been "too predictable, too popular".

The choice of the 2004 winner, Elfriede Jelinek, drew criticism from within the academy itself. Knut Ahnlund, who had not played an active role in the academy since 1996, resigned after Jelinek received the award, saying that picking the author had caused "irreparable damage" to the award's reputation.

TV and radio personality Gert Fylking started the tradition of shouting 'Äntligen!', Swedish for 'At last!', at the announcing of the award winner, as a protest to the academies constant nomination of "authors more or less unknown to the general public". Fylking later agreed to stop his outburst, though the tradition has been carried on by others.

Nobel Prize in Peace

According to Alfred Nobel's will, the Peace Prize should be awarded "to the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between the nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses".

The Peace Prize is awarded annually in Norway’s capital city of Oslo, unlike the Nobel prizes in economics, physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, and literature which are awarded in Stockholm, Sweden. For the past decade, the Nobel Peace Prize Ceremony at the Oslo City Hall has been followed the next day by the Nobel Peace Prize Concert, which is broadcast to more than 150 countries and more than 450 million households worldwide. The Concert has received worldwide fame and the participation of top celebrity hosts and performers.

The Norwegian Parliament appoints the Norwegian Nobel Committee, which selects the Laureate for the Peace Prize. The Committee chairman, currently Dr. Ole Danbolt Mjøs, awards the Prize itself. At the time of Alfred Nobel's death Sweden and Norway were in a personal union in which the Swedish government was solely responsible for foreign policy, and the Norwegian Parliament responsible only for Norwegian domestic policy. Alfred Nobel never why he wanted a Norwegian rather than Swedish body to award the Peace Prize, and many have speculated about Nobel's intentions. Some believe Nobel may have wanted to prevent the manipulation of the selection process by foreign powers, and as Norway did not have any foreign policy, the Norwegian government could avoid influence.

Nommination Process

Nominations for the Prize may be made by a broad array of qualified individuals, including former recipients, members of national assemblies and congresses, university professors, international judges, and special advisors to the Prize Committee. Over time many individuals have become known as "Nobel Peace Prize Nominees", but this designation has no official standing. Nominations from 1901 to 1951, however, have been released in a database. When the past nominations were released it was discovered that Adolf Hitler was nominated in 1939, though the nomination was retracted in February of the same year. Other infamous nominees included Joseph Stalin and Benito Mussolini.

Unlike the other Nobel Prizes, the Nobel Peace Prize may be awarded to persons or organizations that are in the process of resolving an issue, or creating world peace rather than upon the resolution of the issue. Since the Prize can be given to individuals involved in ongoing peace processes, some of the awards now appear, with hindsight, questionable, particularly when those processes failed to bear lasting fruit. For example, the awards given to Theodore Roosevelt, Shimon Peres, Yasser Arafat, Lê Ðức Thọ, and Henry Kissinger were particularly controversial and criticized; the latter prompted two dissenting Committee members to resign. Right-leaning groups have also criticized the Nobel Committee for a perceived left-leaning bias in its decisions.

In 2005, the Nobel Peace Center opened. It serves to present the Laureates, their work for peace, and the ongoing problems of war and conflict around the world.

Controversies

The Nobel Peace Prize has throughout its history sparked controversy. The Norwegian Parliament appoints the Peace Prize Committee, but pacifist critics argue that the same Parliament has pursued partisan military aims by ratifying membership in NATO in 1949, by hosting NATO troops, and by leasing ports and territorial waters to US ballistic missile submarines in 1983. However, the Parliament has no say in the award issue. A member of the Committee cannot at the same time be a member of the Parliament, and the Committee includes former members from all major parties, including those parties that oppose NATO membership.

A particular claimed weakness of the Nobel Peace Prize awarding process is the swiftness of recognition. The scientific and literary Nobel Prizes are usually issued in retrospect, often two or three decades after the intellectual achievement, thus representing a time-proven confirmation and balance of approval by the established academic community, seldom contradicted by newer developments. In contrast, the Nobel Peace Prize at times takes the form of summary judgment, being issued in the same year as or the year immediately following the political act. Some commentators have suggested that to award a peace prize on the basis of unquantifiable contemporary opinion is unjust or possibly erroneous, especially as many of the judges cannot themselves be said to be impartial observers. The 20th Century fight against Communism is one example that stands out most noticeably in this regard. This situation may be said to have deprived the 'real' peace makers, who may not have been recognized for their long-term or subtle approaches. Others maintain the uniqueness of the Peace Prize in that its high profile can often focus world attention on particular problems and possibly aid in the peace-efforts themselves.

On closer inspection, the peace-laureates often have a lifetime's history of working at and promoting humanitarian issues, as in the examples of German medic Albert Schweitzer (1952 laureate), civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (1964 laureate); Catholic missionary Mother Teresa; and Aung San Suu Kyi, a Buddhist nonviolent pro-democracy activist (1991 laureate). Still others are selected for tireless efforts, as in the examples of Jimmy Carter and Mohamed ElBaradei. Others, even today, are quite controversial, due to the recipient's political activity, as in the case of Henry Kissinger (1973 laureate), Mikhail Gorbachev (1990 laureate) or Yasser Arafat (1994 laureate) whose Fatah movement began, and still serves, as a terrorist organization. Finally, the Peace Prize draws criticism for candidates whom it overlooks, such as Mahatma Gandhi, Pope John XXIII, Steve Biko, Hélder Câmara, Raphael Lemkin and Oscar Romero.

Mahatma Gandhi never received the Nobel Peace Prize, though he was nominated for it five times between 1937 and 1948. Einstein commented "Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this (Gandhi) ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth.". Martin Luther King, Jr. was also known to have been inspired by Gandhi's example and espousal of non-violence resistance movement in the independence struggle of India: Gandhi had also been known, though, to make—at times shocking, at times controversial—life's statements and personal philosophy bordering on extreme idealism and racial judgments. Decades later, though, the Nobel Committee publicly declared its regret for the omission. The Nobel Committee may have tacitly acknowledged its error, however, when in 1948 (the year of Gandhi's death), it made no award, stating "there was no suitable living candidate". Similarly, when the Dalai Lama was awarded the Peace Prize in 1989, the chairman of the committee said that this was "in part a tribute to the memory of Mahatma Gandhi". The official Nobel e-museum has an article discussing the issue.

Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics

The Nobel Prize in Economics is a prize awarded each year for outstanding intellectual contributions in the field of economics. The award was instituted by the Bank of Sweden, the world's oldest central bank, at its 300th anniversary in 1968. Although it was not one of the awards established in the will of Alfred Nobel, economics laureates receive their diploma and gold medal from the Swedish monarch at the same December 10 Stockholm ceremony as the other Nobel laureates. The amount of money awarded to the economics laureates is also equal to that of the other prizes.

The prestige of the prize derives in part from its association with the awards created by Alfred Nobel's will, an association which has often been a source of controversy. The prize is commonly referred to as the Nobel Prize in Economics or, more correctly, as the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics.

In February 1995, it was decided that the economics prize be essentially defined as a prize in social sciences, opening the Nobel Prize to great contributions in fields like political science, psychology, and sociology. The Economics Prize Committee has also undergone changes to require two non-economists to decide the prize each year, whereas previously the prize committee had consisted of five economists.

The economics laureates, like the Nobel laureates in chemistry and physics, are chosen by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Nominations of about one hundred living persons are made each year by qualified nominators and are received by a five to eight member committee, which then submits its choice of winners to the Nobel Assembly for its final approval. As with the other prizes, no more than three people can share the prize for a given year and they must be living at the time the prize is awarded. The final award is made in Stockholm and is accompanied by a sum of money.

Criticisms of the Nobel Prizes

The Nobel Prizes have been criticized over the years, with people suggesting that formal agreements and name recognition are more important than actual achievements in the process of deciding who is awarded a Prize. Perhaps the most infamous case of this was in 1973 when Henry Kissinger and Le Duc Tho shared the Peace Prize for bringing peace to Vietnam, even though the War in Vietnam was ongoing at the time. Le Duc Tho declined the award, for the stated reason that peace had not been achieved.

It is said that Mahatma Gandhi was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize five times in between 1937 to 1948 but indeed never won it. Research indicates that the Authority was probably planning to give him the award in 1948; however, he was assassinated in that year. The committee reportedly considered a posthumous award but ultimately decided against it, instead choosing not to award the Nobel Peace Prize to anybody for that particular year.

The strict rules against a Nobel Prize being awarded to more than three people at once is also a cause for controversy. Where a prize is awarded to recognize an achievement by a team of more than three collaborators, inevitably one or more will miss out. For example, in 2002, a Prize was awarded to Koichi Tanaka and John Fenn for the development of mass spectrometry in protein chemistry, failing to recognize the achievements of Franz Hillenkamp and Michael Karas of the Institute for Physical and Theoretical Chemistry at the University of Frankfurt.

Similarly, the rule against posthumous prizes often fails to recognize important achievements by a collaborator who happens to have died before the prize is awarded. For example, Rosalind Franklin made some of the key developments into the discovery of the structure of DNA in 1953, but she died of ovarian cancer in 1958 and the Prize was awarded to Francis Crick, James D. Watson and Maurice Wilkins, one of Franklin's collaborators, in 1962.

Criticism was levied towards the 2005 Nobel Prize in Physics, specifically the recognition of Roy Glauber and not George Sudarshan for the award. Arguably, Sudarshan's work is the more accepted of the two. Though Glauber did publish his work first in 1963, Sudarshan's work later that same year is the work upon which most of quantum optics is based.

The Nobel Prizes are also criticized for their lack of a mathematics award. There are several possible reasons why Nobel created no Prize for mathematics. Nobel's will speaks of prizes for those inventions or discoveries of greatest practical benefit to mankind, possibly having in mind practical rather than theoretical works. Mathematics was not considered a practical science from which humanity could benefit, a key purpose for the Nobel Foundation.

One other possible reason was that there was already a well known Scandinavian prize for mathematicians. The existing mathematical awards at the time were mainly due to the work of Gösta Mittag-Leffler, who founded the Acta Mathematica, a century later still one of the world's leading mathematical journals. Through his influence in Stockholm he persuaded King Oscar II to endow prize competitions and honor distinguished mathematicians all over Europe, including Hermite, Joseph Louis François Bertrand, Weierstrass, and Henri Poincaré.

In 2001, the government of Norway began awarding the Abel Prize, specifically with the intention of being a substitute for the missing mathematics Nobel. Beginning in 2004, the Shaw Prize, which resembles the Nobel Prize, included an award in mathematical sciences. The Fields Medal is often described as the "Nobel Prize of mathematics", but the comparison is not very apt because the Fields is limited to mathematicians not over forty years old.

Recipients who did not receive their award in person

Carl von Ossietzky, the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize winner—was at first required by the Nazi government to decline the Nobel Prize, a demand that Ossietzky did not honor, and then was practically 'prevented' by the same government from going to Olso personally to accept the Nobel Prize (kept under surveillance actually—a virtual 'house arrest'—in a civilian hospital until his demise in 1938), though the German Propaganda Ministry was known to have publicly declared Ossietzky's total freedom to go to Norway to accept the award. After this incident—in 1937—the German government decreed that in the future no German could accept any Nobel Prize.

Andrei Sakharov, the first Soviet Citizen to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, in 1975, was not allowed to receive or personally travel to Oslo to accept the prize. He was described as "a Judas" and a "laboratory rat of the West" by the Soviet authorities. His wife, Elena Bonner, who was in Italy for medical treatment, received the prize in her husband's stead and presented the Nobel Prize acceptance speech by proxy.

Aung San Suu Kyi was awarded the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize but was not allowed to make any formal acceptance speech or statement of any kind to that effect, nor leave Myanmar (Burma) to receive the Prize. Her sons Alexander and Kim accepted the Nobel Peace Prize on her behalf.

Elfriede Jelinek was awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize in Literature but declined to go in person to Stockholm to receive the Prize, citing severe social phobia and mental illness. She made a video instead and wrote out the speech text to be read out in lieu.

Harold Pinter was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2005, but was unable to attend the ceremonies owing to poor health. He, too, delivered his controversial, 'all-defying' speech via video.

Repeat Recipients

In the history of the Nobel Prize, there have been only four people to have received two Nobel Prizes; Marie Curie, Linus Pauling, John Bardeen and Frederick Sanger.

Curie was awarded the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics after discovering radioactivity. She was later awarded the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry after her isolation of radium.

Linus Pauling received the 1954 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for construction of the Hybridized Orbital Theory, and later the 1962 Nobel Peace Prize for activism in regards to the Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty.

John Bardeen was awarded both the 1956 and 1972 Nobel Prize in Physics for the invention of transistor, and later his Theory of Superconductivity.

Frederick Sanger was awarded both the 1958 and 1980 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for identifying the structure of the insulin molecule, and later for his virus nucleotide sequencing.

Additionally, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1917, 1944, and 1963. The first two prizes were specifically in recognition of the group's work during the world wars.

External links

- Nobelprize.org — Official site

- The Nobel Prize Internet Archive

- The Nobel Committees of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- The Nobel Committee of the Karolinska Institute

- The Swedish Academy

- The Norwegian Nobel Committee

- Britannica Spotlight: Guide to the Nobel Prizes

- CNN: Nobel Centennial

- Norwegian Nobel Committee

- The Nomination Database for the Nobel Prize in Peace, 1901-1951

- Nobel Prize for Peace Better World Links

- Laureates at the Nobel foundation

- Winners of the Prize in Economics

- History of the prize and its controversy

- The Nobel Prize in Literature - Laureates

- Nobel Prize Winners in Literature

- The Nobel Prize

- Written in Stone - Burial locations of literary figures.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Nobel Foundation. Nobel Prize Facts. Retrieved on July 30, 2006.

- Øyvind Tønnesson. With Fascism on the Doorstep: The Nobel Institution in Norway, 1940-1945. Retrieved on September 4, 2006.

- The History Channel, This Day in History. First Nobel Prizes: December 10, 1901. Retrieved on July 30, 2006.

- Nobel Foundation. Nomination and Selection Process. Retrieved on July 30, 2006.

- The Scientist, Volume 3, Issue 1, Page 20021211-03. Nobel Prize controversy. Retrieved on July 30, 2006.

- Nobel Foundation. The Discovery of the Molecular Structure of DNA - The Double Helix. Retrieved on July 30, 2006.

- The Nobel Prize Internet Archive. Why is there no Nobel Prize in Mathematics?. Retrieved on July 30, 2006.

- Public Broadcasting Service. The Prize: Controversy and Landmarks. Retrieved on July 30, 2006.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Nobel_Prize history

- Nobel_Prize_in_Literature history

- Nobel_Prize_in_Economics history

- Nobel_Peace_Prize history

- Nobel_Prize_controversies history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ "Edison and Tesla Win Nobel Prize in Physics", Literary Digest, December 18, 1915.

- ↑ Cheney, Margaret, Tesla: Man Out of Time , ISBN 0-13-906859-7.

- ↑ Seifer, Marc J., Wizard, the Life and Times of Nikola Tesla, ISBN 1-559723-29-7 (HC), ISBN 0-806519-60-6 (SC).

- ↑ O'Neill, John H., Prodigal Genius, ISBN 0-914732-33-1.

- ↑ "General Relativity Survives Gruelling Pulsar Test: Einstein At Least 99.95 Percent Right", Particle Physics & Astronomy Research Council, September 14, 2006.

- ↑ "Lilienfeld Biodata".

- ↑ "Renormalized Relations in Condensed Matter", Physics Online Letters.

- ↑ Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles and Momentous Discoveries.

- ↑ The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1962.

- ↑ Wainwright, Milton "A Response to William Kingston, "Streptomycin, Schatz versus Waksman, and the balance of Credit for Discovery"", Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences - Volume 60, Number 2, April 2005, pp. 218-220, Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Horace Freeland Judson, The Great Betrayal: Fraud in Science, 1st. Ed., 2004.

- ↑ Brenda Maddox, Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA, 2002, ISBN 0-06-018407-8.

- ↑ Weiss R.A., Viral RNA-dependent DNA polymerase in virions of Rous sarcoma virus, Reviews in Medical Virology, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 3-11(9), Jan/Mar 1998.