Meteoroid

- "Meteor" redirects here.

A meteoroid is a small body of debris in the Solar System, roughly ranging in size from a sand particle to a boulder. If the body is larger, it is called an asteroid; if smaller, it is known as interplanetary dust. The visible path of a meteoroid that enters Earth's (or another body's) atmosphere is called a meteor, also referred to as a shooting star or falling star. A group of meteors appearing around the same time is called a meteor shower. The root word meteor comes from the Greek meteōros, meaning "high in the air."

Definitions of meteoroid

The current definition of a meteoroid given by the International Meteor Organization is, "A solid object moving in interplanetary space, of a size considerably smaller than an asteroid and considerably larger than an atom or molecule."[1] The Royal Astronomical Society has proposed a new definition, where a meteoroid is between 100 micrometers (µm) and 10 meters (m) across.[2] The near-earth object (NEO) definition includes larger objects, up to 50 m in diameter, in this category.

Meteor

A meteor is the visible event that appears

When a meteoroid or asteroid enters Earth's atmosphere and becomes brightly visible. For bodies on a size scale larger than the atmospheric mean free path (10 cm to several meters), the visibility is due to the heat produced by the ram pressure (not friction, as is commonly assumed) of atmospheric entry. Since the majority of meteors are from small sand-grain size meteoroid bodies, most visible signatures are caused by electron relaxation following the individual collisions between vaporized meteor atoms and atmospheric constituents. The meteor is simply the visible event rather than an object itself.

Fireball

A fireball is brighter than a usual meteor. The International Astronomical Union defines a fireball as "a meteor brighter than any of the planets" (magnitude -4 or greater).[3] The International Meteor Organization (an amateur organization that studies meteors) has a more rigid definition. It defines a fireball as a meteor that would have a magnitude of -3 or brighter if seen at zenith. This definition corrects for the greater distance between an observer and a meteor near the horizon. For example, a meteor of magnitude -1 at 5 degrees above the horizon would be classified as a fireball because if the observer had been directly below the meteor it would have appeared as magnitude -6.[4]

Bolide

The word bolide comes from the Greek βολις, (bolis) which can mean a missile or to flash. The IAU has no official definition of bolide and generally considers the term synonymous with fireball. The term is more often used among geologists than astronomers where it means a very large impactor. For example, the USGS uses the term to mean a generic large crater forming projectile "to imply that we do not know the precise nature of the impacting body ... whether it is a rocky or metallic asteroid, or an icy comet, for example".[5] Astronomers tend to use the term to mean an exceptionally bright fireball, particularly one that explodes (sometimes called a detonating fireball).

Meteorite

A meteorite is a portion of a meteoroid or asteroid that survives its passage through the atmosphere and impact with the ground without being destroyed. Meteorites are sometimes, but not always, found in association with hypervelocity impact craters; during energetic collisions, the entire impactor may be vaporized, leaving no meteorites.

Tektite

Molten terrestrial material "splashed" from a crater can cool and solidify into an object known as a tektite. These are often mistaken for meteorites.

Meteoric dust

Most meteoroids are destroyed when they enter the atmosphere. The left-over debris is called meteoric dust or just meteor dust. Meteor dust particles can persist in the atmosphere for up to several months. These particles might affect climate, both by scattering electromagnetic radiation and by catalyzing chemical reactions in the upper atmosphere.

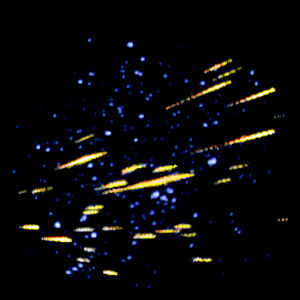

Ionization trails

During the entry of a meteoroid or asteroid into the upper atmosphere, an ionization trail is created, where the molecules in the upper atmosphere are ionized by the passage of the meteor. Such ionization trails can last up to 45 minutes at a time. Small, sand-grain sized meteoroids are entering the atmosphere constantly, essentially every few seconds in a given region, and thus ionization trails can be found in the upper atmosphere more or less continuously. When radio waves are bounced off these trails, it is called meteor burst communications.

Meteor radars can measure atmospheric density and winds by measuring the decay rate and Doppler shift of a meteor trail.

Sound

Numerous people have over the years reported sounds being heard while bright meteors flared overhead. This would seem impossible, given the relatively slow speed of sound. Any sound generated by a meteor in the upper atmosphere, such as a sonic boom, should not be heard until many seconds after the meteor disappeared. However, in certain instances, for example during the Leonid meteor shower of 2001, several people reported sounds described as "crackling," "swishing," or "hissing"[6] occurring at the same instant as a meteor flare. Similar sounds have also been reported during intense displays of Earth's auroras.

Many investigators believe the sounds to be imaginary... essentially sound effects added by the mind to go along with a light show. However, the persistence and consistency of the reports have caused others to wonder. And sound recordings made under controlled conditions in Mongolia in 1998 by a team lead by Slaven Garaj, a physicist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology at Lausanne, support the contention that the sounds are real.

How these sounds could be generated, assuming they are in fact real, remains something of a mystery. It has been hypothesized that the turbulent ionized wake of a meteor interacts with the magnetic field of the Earth, generating pulses of radio waves. As the trail dissipates, megawatts of electromagnetic energy could be released, with a peak in the power spectrum at audio frequencies. Physical vibrations induced by the electromagnetic impulses would then be heard if they are powerful enough to make grasses, plants, eyeglass frames, and other conductive materials vibrate.[7][8][9][10] This proposed mechanism, although proven to be plausible by laboratory work, remains unsupported by corresponding measurements in the field.

Formation

Many meteoroids are formed by impacts between asteroids though many are also left in trails behind comets that form meteor showers and many members of those trails are eventually scattered into other orbits forming random meteors too. Other sources of meteors are known to have come from impacts on the Moon, or Mars as some meteorites from them have been identified. See Lunar meteorites and Mars meteorites.

Orbit

Meteoroids and asteroids orbit around the Sun, in greatly differing orbits. Some of these objects orbit together in streams; these are probably comet remnants that would form a meteor shower. Other meteoroids are not associated with any stream clustering (although there must also be meteoroids clustered in orbits which do not intercept Earth's or any other planet). The fastest objects travel at roughly 42 kilometers per second (26 miles per second) through space in the vicinity of Earth's orbit. Together with the Earth's orbital motion of 29 km/s (18 miles per second), collision speeds can reach 71 km/s (44 miles per second) during head-on collisions. This would only occur if the meteor were in a retrograde orbit. Meteors have roughly a fifty percent chance of a daylight (or near daylight) collision with the Earth as the Earth orbits in the direction of roughly west at noon. Most meteors are however, observed at night as low light conditions allow fainter meteors to be observed. Meteors are usually seen when they are 60 to 120 km (40 to 75 miles) above the ground.[11]

A number of specific meteors have been observed, largely by members of the public and largely by accident, but with enough detail that orbits of the incoming meteors or meteorites have been calculated. All of them came from orbits from the vicinity of the Asteroid Belt.[12]

Perhaps the best-known meteor/meteorite fall is the Peekskill Meteorite which was filmed on October 9, 1992 by at least 16 independent videographers.[13]

Eyewitness accounts indicate that the fireball entry of the Peekskill meteorite started over West Virginia at 23:48 UT (±1 min). The fireball, which traveled in a northeasterly direction had a pronounced greenish color, and attained an estimated peak visual magnitude of -13. During a luminous flight time that exceeded 40 seconds the fireball covered a ground path of some 700 to 800 km.

One meteorite recovered at Peekskill, N.Y., for which the event and object gained its name, (at 41.28 deg. N, 81.92 deg. W) had a mass of 12.4 kg (27 lb) and was subsequently identified as an H6 monomict breccia meteorite.[14] The video record suggests that the Peekskill meteorite probably had several companions over a wide area especially in the harsh terrain in the vicinity of Peekskill.

Spacecraft damage

Even very small meteoroids can damage spacecraft. The Hubble Space Telescope for example, has about 572 tiny craters and chipped areas.[15]

Gallery

See also

- North American Meteor Network

- International Meteor Organization

- American Meteor Society (AMS)

- Baetylus

- Impact crater

- Meteor shower

- Meteorite

- Tektite

- Tollmann's hypothetical bolide

- Green fireballs

- Impact event

| |||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ Glossary, International Meteor Organization. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ↑ Beech, M., Duncan I. Steel. 1995. On the Definition of the Term Meteoroid. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 36 (3): 281–284. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ↑ MeteorObs Explanations and Definitions (states IAU definition of a fireball). meteorobs.org. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ↑ International Meteor Organization - Fireball Observations. IMO. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ↑ What is a Bolide? USGS. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ↑ Burdick, Alan. 2002. Psst! Sounds like a meteor: in the debate about whether or not meteors make noise, skeptics have had the upper hand until now - Now Hear This. Natural History. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ↑ Listening to Leonids. NASA. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ↑ Sommer, H.C. and H.E. Von Gierke. 1964.Hearing Sensations in Electric Fields. John Dawes2. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ↑ Frey, Allan H. 1962. Human auditory system response to Modulated electromagnetic energy. John Dawes2. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ↑ Human Perception of Illumination with Pulsed Ultrahigh-Frequency Electromagnetic Energy. John Dawes2. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ↑ Meteors. World Book @ NASA. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ↑ The Peekskill Meteorite and Fireball. uregina.ca. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ↑ The Peekskill Meteorite October 9, 1992 Videos. aquarid.physics.uwo.ca. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ↑ Wlotzka, F. 1994. Meteoritical Bull. Meteoritics. 75:28:5:692.

- ↑ How Hubble Has Survived a Decade of Impacts. SPACE.com. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Atkinson, Austen. 2000. Impact Earth: Asteroids, Comets and Meteoroids, the Growing Threat. London, UK: Virgin. ISBN 0753504014.

- Murad, Edmond and Iwan P. Williams. 2002. Meteors in the Earth's Atmosphere: Meteoroids and Cosmic Dust and their Interactions with the Earth's Upper Atmosphere. Cambridge, UK; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521804310.

- Spangenburg, Ray, Kit Moser, and Diane Moser. 2002. Meteors, Meteorites, and Meteoroids. New York, NY: Franklin Watts. ISBN 0531119254.

External links

- Meteoroids Page at NASA's Solar System Exploration. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- International Meteor Organization fireball page. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- British Astronomical Society fireball page. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- A Goddard Space Flight Center Science Question of the Week where the answer mentions that a fireball will cast a shadow. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- Meteor shower predictions. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- Society for Popular Astronomy - Meteor Section. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.