Louvre

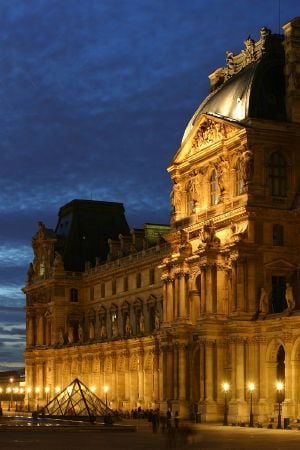

The Louvre Museum (French: Musée du Louvre) in Paris, France, is one of the oldest, largest, and most famous art galleries and museums in the world. The Louvre has a long history of artistic and historic conservation, inaugurated in the Capetian dynasty until today. The building was previously a royal palace and holds some of the world's most famous works of art, such as Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa, The Virgin and Child with St. Anne, Madonna of the Rocks, Jacques Louis David's Oath of the Horatii, Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People, and Alexandros of Antioch's Venus de Milo.

Located in the center of the French capital, between the Rive Droite of the Seine and the rue de Rivoli in the 1st arrondissement, the Louvre is accessed by the Palais Royal — Musée du Louvre Metro station. The equestrian statue of Louis XIV constitutes the starting point axe historique, but the palace is not aligned on this axis.

The Louvre houses 35,000 works of art displayed in eight curatorial departments: Near Eastern Antiquities; Islamic Art; Paintings; Egyptian Antiquities; Sculptures; Prints and Drawings; Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiquities; and Decorative Arts. With a record 8.3 million visitors in 2006, the Louvre is the most visited art museum in the world. Due to the variety of the collections and the size of the museum—555,000 square feet— visitors are encouraged to take a thematic or cross-departmental approach in seeing exhibits.

History

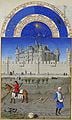

The first royal "Castle of the Louvre" was founded in what was then the western edge of Paris by Philip Augustus in 1190, as a fortified royal palace to defend Paris on its west against Viking attacks. The first building in the existing Louvre was begun in 1535, after demolition of the old Castle. The architect Pierre Lescot introduced to Paris the new design vocabulary of the Renaissance, which had been developed in the châteaux of the Loire.

- CastleLouvreModel.jpg

Model of the first royal "Castle of the Louvre"

- Grand Gallery Louvre.jpg

The Gallery of nineteenth-century French School

During his reign (1589–1610), King Henry IV added the Grande Galerie. Henry IV, a promoter of the arts, invited hundreds of artists and craftsmen to live and work on the building's lower floors. This huge addition was built along the bank of the River Seine and at the time was the longest edifice of its kind in the world.

Louis XIII (1610–1643) completed the Denon Wing, which had been started by Catherine Medici in 1560. Today, it has been renovated, as a part of the Grand Louvre Renovation Program.

The Richelieu Wing was also built by Louis XIII. It was part of the Ministry of Economy of France, which took up most of the north wing of the palace. The Ministry was moved and the wing was renovated and turned into magnificent galleries which were inaugurated in 1993, the two-hundreth anniversary of parts of the building first being opened to the public as a museum on November 8, 1793, during the French Revolution. Napoleon I built the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel (Triumph Arch) in 1805 to commemorate his victories and the Jardin du Carrousel. In those times this garden was the entrance to the Palais des Tuileries.

The Louvre was still being added to by Napoleon III. The new wing of 1852–1857, by architects Visconti and Hector Lefuel, represents the Second Empire's version of Neo-baroque, full of detail and laden with sculpture. (Work continued until 1876.)

During the uprising of the Paris Commune in 1871, the Tuileries was burned. Paradoxically, the disappearance of the gardens, which had originally brought about the extension of the Louvre, opened the admirable perspective that now stretches from the Arc du Carrousel west through the Tuileries and the Place de la Concorde to the Place Charles de Gaulle.

In the late 1980s, the Louvre embarked upon an aggressive program of renovation and expansion. When the first plans by the Chinese-American architect Ieoh Ming Pei were unveiled in 1984, that included a glass pyramid in the central courtyard that would serve as the museum's main entrance.

In November 1993, to mark its two-hundreth anniversary, the museum unveiled the Richelieu Wing in the quarters that had been vacated, grudgingly, by the Ministry of Finance in 1989. This expansion, which completed the museum's occupancy of the palace complex, added 230,000 square feet to the existing 325,000 square feet of exhibition space, and allowed it to put an additional 12,000 works of art on display in 165 new rooms.

Louvre Pyramid

The Louvre Pyramid was built on the axis of the French Revolution. The central courtyard, on the axis of the Champs-Élysées, is occupied by the Louvre Pyramid, built in 1989, and serves as the main entrance to the museum.

The Louvre Pyramid is a large glass pyramid commissioned by then French president François Mitterrand, designed by I. M. Pei and was inaugurated in 1989. This was the first renovation of the Grand Louvre Project. The Carre Gallery, where the Mona Lisa was exhibited, was also renovated. The pyramid covers the Louvre entresol and forms part of the new entrance into the museum.

Le Louvre-Lens

Since many of the works in the Louvre are viewed only in distinct departments - for example, French Painting, Near Eastern Art, or Sculpture - established some 200 years ago, it was decided that a satellite building would be created outside of Paris, to experiment with other museological displays and to allow for a larger visitorship outside the confines of the Paris Palace. Sourced from the Louvre's core holdings, and not from long-lost or stored works in the basement of the Louvre, as widely thought, the new satellite will show works side-by-side, cross-referenced and juxtaposed from all periods and cultures, creating an entirely new experience for the museum visitor.

The project completion is planned for late 2010; the building will be capable of receiving between 500 and 600 major works, with a core gallery dedicated to the human figure over several millenia. This new building should receive about 500,000 visitors per year. There were orginally six city candidates for this project: Amiens, Arras, Boulogne-sur-Mer, Calais, Lens, and Valenciennes. On November 29, 2004, French Prime Minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin chose Lens, Pas-de-Calais to be the site of the new Louvre building. Le Louvre-Lens was the name chosen for the museum.

The new satellite museum, funded by the local regional government, the Nord-Pas-de-Calais, will have 236,806 square feet of usable space built on two levels, with semi-permanent exhibition space covering at least 53,820 square feet. There will also be space set aside for rotating temporary exhibitions. The project will also feature a multi-purpose theater and visitable conservation spaces. The building is comprised of a series of low-laying spaces clad in glass and stainless steel in the middle of a 60 acres former mining site, largely reclaimed by nature. The new satellite building, with an estimated cost of $96.6 million, was selected after an international architectural competition in 2005.

The architectural joint-venture team of SANAA of Tokyo and the New York-based IMREY CULBERT LP were awarded the project on September 26, 2005. SANAA is a widely recognized Japanese architectural firm, noted for their ethereal designs. IMREY CULBERT is an American/French architectural firm, specializing in museum and exhibit designs, with offices in New York and Paris. Tim Culbert, project architect that lead the team's submission for the Louvre-Lens project, was previously an associate-partner of I.M. Pei, architect of the Pyramid of the Louvre.

Access

The station is named after the nearby Palais Royal and the Louvre. Until the 1990s, its name was Palais Royal; it was renamed when a new access was built from the station to the underground portions of the redeveloped Louvre Museum.

Management

Long managed by the French state under the Réunion des Musées Nationaux, the Louvre has recently acquired powers of self-management as an Etablissement Public Autonome ("government-owned corporation) in order better to manage its growth.

Directors

The director of the Louvre has in the past been known as its "Conservateur," and is now known as its "président directeur général." These have included:

- Dominique Vivant: 1804-1815

- Michel Delignat-Lavaut: ?-1987

- Michel Laclotte: 1987-1994

- Pierre Rosenberg: 1994-2001

- Henri Loyrette: 2001-present

Curatorial departments

The Louvre's collection covers Western art from the medieval period to 1848, formative works from the civilizations of the ancient world, and works of Islamic art. The collection is grouped into eight Departments, each shaped and defined by the activities of its curators, collectors and donors.

Near Eastern Antiquities

The Department of Near Eastern Antiquities is devoted to the ancient civilizations of the Near East and encompasses a period that extends from the first settlements, which appeared more than 10,000 years ago, to the advent of Islam.

Creation of the collection

The first archaeological excavations in the mid-nineteenth century unearthed these lost civilizations, and their art was rightly considered to be among humanity's greatest creative achievements. The Department of Near Eastern Antiquities—-the youngest of the Louvre's departments up until the recent creation of the Department of Islamic Art-—was established in 1881. The archaeological collections were essentially formed during the nineteenth century and in the twentieth century up until World War II. Rivaled only by the British Museum and the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin, this collection offers a comprehensive overview of these different civilizations, drawing on scientific excavations conducted on numerous archaeological sites. The first of these excavations took place between 1843 and 1854 in Khorsabad, a city constructed by King Sargon II of Assyria in the eighth century B.C.E. This site brought to light the Assyrians and lost civilizations of the Near East. One of the aims of the Louvre, which played a leading role in this rediscovery, is to reveal the depth of the region’s cultural roots and its enduring values.

Egyptian Antiquities

The Department of Egyptian Antiquities presents vestiges from the civilizations that developed in the Nile Valley from the late prehistoric era (c. 4000 B.C.E.) to the Christian period (fourth century AD).

Enriching the collection

Prior to Champollion, the Muséum Central des Arts exhibited Egyptian statues from the former royal collections. Several major sculptures were added to this collection under Louis XVIII, including Nakhthorheb and Sekhmet.

Between 1824 and 1827, a department was created with the arrival of entire collections (9,000 works). From 1852 to 1868, the works gathered by European collectors who had pursued careers in Egypt were also added to the rooms. These included the collections of Dr. Clot, Count Tyszkiewicz, and the French consul Delaporte. Many of these works (a gold bowl, a mummified cat) are extraordinary, even though their provenance generally remains unknown. The Louvre sent French archaeologist Mariette to Egypt, where he discovered the Serapeum at Saqqara. Between 1852 and 1853, he sent 5,964 works to Paris, including the famous Seated Scribe. He became the first director of Egyptian Antiquities and protected the sites from pillagers. There followed an era during which Western museums shared objects unearthed at archaeological sites directed by scientists on concessions attributed by the Egyptian government, notably for the excavations of Abu Roash, Assiut, Bawit, Medamud, Tod, and Deir el-Medina.

Certain major works entered the museum through the generosity of individuals: American collector Atherton Curtis bequeathed 1,500 objects before and after World War II, and the Société des Amis du Louvre has provided constant support, as in 1997, with the rare statue of Queen Weret.

Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiquities

This department oversees works from the Greek, Etruscan, and Roman civilizations, illustrating the art of a vast area that encompasses Greece, Italy, and the whole of the Mediterranean basin, spanning a period that stretches from Neolithic times (4th millennium B.C.E.) to the 6th century AD.

Musée des Antiques

The nucleus of the Greek, Roman, and Etruscan antiquities came from the former royal collections, enriched by property seized during the French Revolution. The Musée des Antiques was established in 1800, occupying the apartments of Anne of Austria. In 1807, over 500 marbles were purchased from the Borghese collection. After the restitution of works to Italy, Visconti conducted an efficient acquisitions policy, buying back works from the Albani collection and marbles from Choiseul-Gouffier (including the Parthenon frieze). The Venus de Milo, presented to Louis XVIII by the Marquis de Rivière in 1821, further enhanced the collection, which mainly consisted of marbles to begin with. This situation changed with the purchase of 600 vases from the Tochon collection and over 2,000 vases from the Durand collection, and the arrival of bronzes and objects from the Cabinet des Antiques at the Bibliothèque Nationale.

The antiquities section was further enriched during the nineteenth century by contributions from archaeological expeditions, notably fragments of the temple at Olympia (a gift from the Greek Senate in 1829, after the scientific expedition of Dubois and Blouet), ancient reliefs from Assos (presented by Sultan Mahmoud II), and the frieze from the Temple of Artemis at Magnesia ad Maeandrum (Texier excavation, 1842).

The purchase of the Campana collection (1861) modified the composition of the department, which moved to the gallery named after the collector in the south wing of the Cour Carrée. The Winged Victory of Samothrace, discovered by Champoiseau in 1863, was installed at the top of the Daru staircase, on a ship's prow brought back in 1883.

Islamic Art

The Department of Islamic Art displays over 1,000 works, most of which were intended for the court or a wealthy elite. They span 1,300 years of history and three continents, reflecting the creativity and diversity of inspiration in Islamic countries.

The creation of the collection

The history of the collection reflects both history in the broadest sense and the history of artistic taste.

Certain objects illustrate the centuries-old relationship between France and the Islamic world. A certain mystery still surrounds the fragments of the shroud of Saint Josse (a piece of tenth-century Iranian cloth), which entered the Louvre in 1922. A king of England, who was very close to two of the most eminent members of the First Crusade, presented the cloth (before 1134) to the Abbey of Saint-Josse, where it was used to wrap the relics of the saint of the same name. The precious cloth was transferred to the Louvre some seven centuries later. The Baptistery of Saint Louis, which belonged (probably as early as the fourteenth century) to the treasury of the Sainte-Chapelle in the Château de Vincennes, was transferred to the Louvre in 1832 on the orders of Louis-Philippe, as indicated by its inventory number (LP). An Ottoman cup which had belonged to Louis XIV featured in the inventory of the Musées Royaux (MR) after the fall of Napoleon.

Sculptures

The rooms devoted to "modern" sculpture, opened in 1824, gradually became the Department of Medieval, Renaissance, and Modern Sculpture. Separate collections were founded in 1848 for antiquities and in 1893 for objets d'art.

Building up the collections

As early as the ancien régime, the Louvre housed a number of medieval and modern sculptures. Unwanted or dismantled royal commissions-—Charles V and Jeanne de Bourbon, Della Robbia's Catherine de' Medicis, groups by Pilon, Puget's Alexander and Diogenes, busts, and a series of famous men made for the future museum-—were stored in what was known as the salle des antiques, now the Salle des Caryatides, on the ground floor of the Cour Carrée. The sculptor Pajou was in charge of the works from 1777 to 1792. The collections of the Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture were kept nearby, including a complete collection of morceaux de réception, busts of patrons, and donations such as Marie Serre and a self-portrait by Coysevox.

When the Muséum Central des Arts opened in 1793, little modern sculpture was on display. Among the few works that went on show were Michelangelo's Slaves, confiscated from émigrés in 1794, and a few busts by artists like Raphael and Carracci. There were also commissioned busts of artists, displayed alongside the painting collections, and above all copies of works from antiquity, including numerous bronze busts. During the Revolution, the most important sculpture collection was in the Musée des Monuments Français which Alexandre Lenoir set up in the former monastery of the Petits Augustins. This museum faced competition from the museum devoted to the French school in the Palais de Versailles, opened in 1801–1802, which displayed, among other works, morceaux de réception for entry to the Académie. The Musée des Monuments Français was closed after the Restoration and some of the finest works were transferred to the Louvre.

Decorative Arts

The Department of Decorative Arts presents a highly varied range of objects, including jewelry, tapestries, ivories, bronzes, ceramics, and furniture. The collection extends from the Middle Ages to the first half of the nineteenth century.

A Collection Steeped in History

The decree issued by the Convention at the founding of the Muséum Central des Arts on July 27, 1793, stipulated that the exhibits would include objet’s d’art. The nucleus of the display was formed by furniture and objects from the former royal collection. Small bronzes and gems joined the collection a little later, in 1796. The department was subsequently enriched by two important [[treasures], from the Sainte Chapelle on the nearby Ile de la Cité and the abbey of Saint-Denis to the north of Paris (including Abbot Suger's collection of vases and the coronation regalia of the kings of France).

The collections were further supplemented thanks to the decree of Germinal 1 year II (March 21, 1794), authorizing the museum to confiscate property belonging to émigré aristocrats who had fled abroad to escape the Revolution. Revolutionary and imperial conquests or purchases brought further riches, such as the shield and helmet of Charles IX. In 1802, when Dominique-Vivant Denon was appointed director of the Musée Central des Arts, the decorative arts collection was administered by the Department of Antiquities (under Ennio Quirino Visconti). By 1818, when Visconti died and was succeeded by the comte de Clarac, the initial collection was somewhat diminished: sixteen objects from Saint-Denis were sold in 1798, Napoleon I requisitioned numerous items for his imperial palaces, and the year 1815 saw the restitution of works acquired as a result of the Napoleonic conquests.

Paintings

The Department of Paintings reflects the encyclopedic scope of the Louvre, encompassing every European school from the thirteenth century to 1848. The collection is overseen by 12 curators, who are among the most renowned experts in their field.

History of the Collection

The Louvre's collection of paintings dates back to the reign of Francis I of France, who sought to create a gallery of art in his château at Fontainebleau rivaling those of the great Italian palaces. He acquired masterpieces by leading Italian masters (Michelangelo, Raphael) and invited Italian artists to his court (Leonardo da Vinci, Rosso, and Primaticcio). The French royal collections grew steadily as successive sovereigns made acquisitions reflecting the tastes and fashions of their time-—Louis XIV's purchase of the collections of the banker Jabach is a prime example. Louis XIV also expanded the collection of Italian paintings. The first Spanish paintings (by Murillo) and a series of French works (Le Sueur) were acquired during the reign of Louis XVI. Works from the Northern schools appeared first during the seventeenth century and, above all, the eighteenth.

In 1793, these works formed the core collection of the Muséum Central des Arts, opened within the Louvre after the Revolution. Throughout the ninettenth century, confiscated French aristocratic collections and the spoils of the Napoleonic conquests brought important new acquisitions. Other works were purchased from individuals (Giampietro Campana) or were acquired through the Paris Salons and donations (the collection of Dr. La Caze in 1869).

With the opening of the Musée d'Orsay in 1986, the collection was split up, with works painted after the 1848 Revolution (including pictures by Courbet and the Impressionists) transferred from the Louvre to the newly renovated Gare d'Orsay.

Prints and Drawings

One of the Louvre's eight departments is devoted to the museum's extraordinary collection of works on paper, which include prints, drawings, pastels, and miniatures. These fragile works feature in temporary exhibitions and can also be viewed privately by arrangement.

A Rich Collection

The Louvre's first exhibition of drawings featured 415 works and took place in the Galerie d'Apollon at 28 Thermidor of the year V (August 15, 1797). The exhibition marked the opening up to the public of the collections of the future Department of Prints and Drawings. Most of the drawings came from the Cabinet du Roi, having been acquired by Louis XIV in 1671 from the collection of the colonial banker E. Jabach. This initial collection was subsequently enriched with drawings by the first royal painters (Le Brun, Mignard, and Coypel) and works from the collection of P.-J. Mariette. After the Revolution, the drawings were stamped with the marks of the Muséum National and the Conservatoire. Further works were seized during military campaigns (the collection of the dukes of Modena), from the Church, and from émigré aristocrats (Saint-Morys and the comte d'Orsay). François-André Vincent, the last Garde des Dessins du Roi (keeper of the king's drawings), was followed by [Morel d'Arleux]], who was appointed Garde des Dessins, Estampes et Planches Gravées (keeper of drawings, prints, and engraved plates) at the Muséum Central des Arts in June 1797. In 1802, d'Arleux became Conservateur du Cabinet des Dessins et de la Chalcographie (curator of the department of drawings and engraved plates).

The department continued to grow, notably with the acquisition in 1806 of four collections comprising nearly 1,200 drawings amassed during the seventeenth century by Filippo Baldinucci, an adviser to Leopoldo de' Medici. D'Arleux died in 1827, and responsibility for the museum's drawings passed to the general secretary of museums, Alphonse de Cailleux, until 1832, when the works were assigned to the curator of paintings. Exhibitions of works on paper were held in the Galerie d'Apollon until the mid-nineteenth century.

Collections

Works of artists like Fragonard, Rembrandt, Rubens, Titian, Poussin, and David can be seen. Among the well-known sculptures in the collection are the Winged Victory of Samothrace and the Venus de Milo.

The collection of Baron Edmond de Rothschild (1845–1934), given to the Louvre in 1935, fills an exhibition room. It contains more than 40,000 engravings, nearly 3,000 drawings, and 500 illustrated books.

Besides art, the Louvre has many other types of exhibits, including archeology, history, sculpture and architecture. It has a large furniture collection, whose most spectacular item used to be the Bureau du Roi of the eighteenth century, now returned to the Palace of Versailles.

Since September 14, 2005, the Louvre museum has gradually forbidden the taking of photos of its artworks. Signs prohibiting photography suggest the consultation of the images on the Louvre online catalogue instead.

Notable paintings

The Louvre painting collections examine European painting in the period from the mid-thirteenth Century (late medieval) to the middle of the nineteenth Century. (Later period paintings like Picasso and Renoir are not found at the Louvre) The paintings are divided into three main groups, The French School, the Italian (Davinci, Rafael, and Boticelli) and the Spanish Schools (Goya), and Northern Europe, English, German, Dutch, and Flemish Schools. Below are representative masterpieces from the different schools and periods in the collections.

Thirteenth to fifteenth century

Saint Francis of Assisi receives the stigmata, Giotto (about 1290–1300), described in 1550 and 1568 by Vasari as being found in the church of San Francesco in Pisa, this retable no doubt comes from one of the transept chapels. Often contested despite the presence of the signature, the attribution of this work to Giotto has been reaffirmed by the majority of specialists. The scenes from the life of St. Francis of Assisi (1182-1226) are comparable to the frescoes depicting the same subject in the Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi that are also attributed to Giotto.

Other work include, The Madonna and Christ Child enthroned with angels, Cimbue (about 1270); Ship of Fools, Hieronymus Bosch (1490–1500); [[Portrait of John II the Good]], anonymous (about 1350), acquired by Louis XV, part of the royal collection; The Virgin with Chancellor Rolin, Jan van Eyck (about 1435), seized in the French Revolution (1796); [[Portrait de Charles VII, Jean Fouquet (1445–1448); The Condottiero, Antonello da Messina (1475); St. Sebastian, Andrea Mantegna (1480); and Self-Portrait with flowers, Albrecht Dürer (1493).

Sixteenth century

- Virginandchildwithstanne.JPG

The Virgin and Child with St. Anne

- Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci (1503–1506), acquired by Francis I in 1519. This portrait was doubtless painted in Florence between 1503 and 1506. It is thought to be of Lisa Gherardini, wife of a Florentine cloth merchant named Francesco del Giocondo—hence the alternative title, La Gioconda. However, Leonardo seems to have taken the completed portrait to France rather than giving it to the person who commissioned it. It was eventually returned to Italy by Leonardo's student and heir Salai. It is not known how the painting came to be in François I's collection.

- The Virgin and Child with St. Anne, Leonardo da Vinci (1508)

- The Virgin and Child with Saint John the Baptist, called La belle jardinière, Raphael (1508). Belonged to the royal collection, acquired by Francis I

- Portrait of Balthazar Castiglione, Raphael (about 1515), acquired by Louis XIV from the estate of Mazarin

- The Wedding at Cana, Paolo Veronese (1562–1563). It hung 8.25 feet from the floor in the San Giorgio Maggiore monastery for 235 years, until it was plundered by Napoleon in 1797

Seventeenth century

- The Lacemaker, Johannes Vermeer, (1669–1670), bought in 1870. Renoir considered this masterpiece, which entered the Louvre in 1870, the most beautiful painting in the world, along with Watteau's Pilgrimage to the Island of Cythera, also in the Louvre. A young lacemaker, undoubtedly a member of the Delft bourgeoisie, is hunched intently over her work, deftly manipulating bobbins, pins and thread on her sewing table. The theme of the lacemaker, frequently depicted in Dutch literature and painting (notably by Caspar Netscher) traditionally illustrated feminine domestic virtues. The small book in the foreground is probably the Bible, which reinforces the picture's moral and religious interpretation. But this is also, as in Vermeer's famous Milkmaid (circa 1658, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), one of the peeks into domestic privacy that so fascinated him. He loved to observe the everyday objects around him and paint different combinations of them in his works: he used the same piece of furniture and Dutch carpet with leaf motifs in several of his pictures.

- Et in Arcadia ego, Nicolas Poussin (1637–1638)

- The pilgrims of Emmaus, Rembrandt (1648), seized in the French Revolution in 1793

- Saint Joseph charpentier, Georges de la Tour (1642), donated in 1948

- The club foot, Joseph de Ribera (1642), bequeathed in 1869

- Le young mendicant, Murillo (about 1650), bought by Louis XVI about 1782

- Bathsheba at Her Bath, Rembrandt (1654, bequeathed in 1869

- Ex Voto, Philippe de Champaigne (1662), seized in the French Revolution in 1793

Eighteenth century

- The Embarkation for Cythera, Antoine Watteau (1717). Watteau took five years to complete this large painting, which he submitted to the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture as his reception piece. The reason it took him so long was that at the same time he was also working on the increasing number of private commissions that his growing reputation brought him. Watteau was given approval to submit the painting in 1712, but only actually submitted it in 1717. The work - The Pilgrimage to Cythera - proved to be one of his masterpieces, and he was admitted to the Academy as a painter of "fêtes galantes" - courtly scenes in an idyllic country setting. But does the work actually depict couples setting out for the island or returning from it? Art historians have come up with a wide variety of interpretations of the allegory of the voyage to the island of love.

- Portrait of Louis XIV, Hyacinthe Rigaud (1701)

- La Raie, Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (before 1728)

- Oath of the Horatii, Jacques-Louis David (1784)

- Master Hare, Joshua Reynolds (1788–1789)

Nineteenth century

- The Turkish bath, Ingres (1862). At the end of his life, Ingres created the most erotic of all his works with this harem scene. In it he combines the figure of the nude with an oriental theme, taking as his inspiration the letters of Lady Montague (1690-1760), who recounts a visit to a women's baths in Instanbul in the early eighteenth century. Ingres has borrowed figures from some of his previous paintings for this composition full of arabesques. This late masterpiece was only revealed to the public many years after his death.

- The Raft of the Medusa, Théodore Géricault (1819)

- Liberty Leading the People, Eugène Delacroix (1830)

- Bonaparte visitant les pestiférés de Jaffa, Antoine-Jean Gros (1804)

Abu Dhabi Louvre

In March 2007, the Louvre announced that a Louvre museum would be completed by 2012 in Abu Dhabi, UAE. The 30-year agreement, signed by French Culture Minister Renaud Donnedieu de Vabres and Sheik Sultan bin Tahnoon Al Nahyan, will prompt the construction of a Louvre museum in downtown Abu Dhabi in exchange for $1.3 billion. It has been noted that the museum will showcase work from multiple French museums, including the Louvre, the Georges Pompidou Center, the Musee d'Orsay, and Versailles. However, Donnedieu de Vabres stated at the announcement that the Paris Louvre would not sell any of its 35,000-piece collection.

The Da Vinci Code

The Louvre and many of its works of art are featured prominently in Dan Brown's novel, The Da Vinci Code and in the 2006 film adaptation. The Louvre is the main setting in the prologue and first few chapters of the book and parts of the movie. The museum is the homicide crime scene where curator Jacques Saunière is murdered by an Opus Dei member named Silas.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bonfante-Warren, Alexandra. Louvre, Universe, 2000. ISBN 978-0883635018

- D'Archimbaud, Nicholas. Louvre: Portrait of a Museum, Harry N. Abrams, 2001. ISBN 978-0810983154

- Gowing, Lawrence. Paintings in the Louvre, Stewart, Tabori, and Chang, 1994. ISBN 978-1556700071

- Laclotte, Michel. Treasures of the Louvre, Tuttle Shokai, Inc., 2002. ISBN 978-4925080026

- Mignot, Claude. The Pocket Louvre: A Visitor's Guide to 500 Works, Abbeville Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0789205780

External links

- Extensive Photo Gallery from The Louvre — Photos of almost all the sculpture, many of the paintings and Objects d'Art

- Fullscreen Virtual Tour by Virtualsweden

- History of the Louvre

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.