Leon Festinger

Leon Festinger (pronounced Feh-sting-er) (May 8, 1919 – February 11, 1989) was a social psychologist from New York City who became famous for his Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (Festinger, 1957). Festinger earned his Bachelor of Science degree from the City College of New York in 1939. After completing his undergraduate studies, he attended the University of Iowa where he received his Ph.D. in 1942. Festinger studied under Kurt Lewin, who is often considered the father of social psychology.

Over the course of his career, Leon Festinger taught at a number of universities, including the University of Iowa, the University of Rochester, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the University of Minnesota, the University of Michigan, and Stanford University. During his years at Stanford in the 1950s and 1960s, he was at the height of his influence,[1] and trained many young social psychologists who would proceed to become influential in their own careers (e.g. Elliot Aronson). In 1968 he went to the New School for Social Research in New York City, where he remained until his death in 1989.

Festinger is best known for his theory of cognitive dissonance, which suggests that inconsistency among beliefs or behaviors will cause an uncomfortable psychological tension, leading to people to change their beliefs to fit their behavior instead of changing one's behavior to fit their belief, as conventionally assumed. Festinger also proposed social comparison theory, according to which people evaluate their own opinions and desires by comparing themselves with others.

Festinger is also known for developing the theory of propinquity, along with Schacter and Back, which refers to the physical or psychological proximity between people and the corresponding likelihood to form friendships based on this proximity.

Life

Born to self-educated Russian-Jewish immigrants Alex Festinger (an embroidery manufacturer) and Sara Solomon Festinger in Brooklyn, New York, Leon Festinger attended Boys' High School and received a bachelor's in science at City College of New York in 1939. He received a Master's in psychology from the University of Iowa in 1942 after studying under prominent social psychologist Kurt Lewin, who was trying to create a "field theory" of psychology (by analogy to physics) to respond to the mechanistic models of the behaviorists.[1]

The same year, he married pianist Mary Oliver Ballou with whom he had three children (Catherine, Richard and Kurt[2]) before divorcing.[1]

Lewin created a Research Center for Group Dynamics at MIT in 1945 and Festinger followed, becoming an assistant professor. Lewin passed away in 1947 and Festinger left to become an associate professor at the University of Michigan, where he was program director for the Group Dynamics center.[1]

In 1951 he became a full professor of psychology at the University of Minnesota. His 1953 book Research Methods in the Behavioral Sciences (with Daniel Katz) stressed the need for well-controlled variables in laboratory experiments, even if this meant misinforming the participants.[1]

In 1955 he moved to Stanford University. Finally, in 1968 he became Staudinger Professor of Psychology at the New School for Social Research in New York.[1]

He remarried the following year to Trudy Bradley, a professor at the NYU School of Social Work. They had no children.[1]

Work

Cognitive dissonance

The theory of cognitive dissonance was developed by Leon Festinger in the mid-1950s, after observing the counterintuitive persistence of members of a UFO doomsday cult and their increased proselytization after their leader's prophecy failed to materialize. Festinger interpreted the failed message of earth's destruction, sent by extraterrestrials to a suburban housewife, as a "disconfirmed expectancy" that increased dissonance between cognitions, thereby causing most members of the impromptu cult to lessen the dissonance by accepting a new prophecy: That the aliens had instead spared the planet for their sake.[3]

The basic theory is as follows. Cognitions which contradict each other are said to be "dissonant." Cognitions that follow from, or fit with, one another are said to be "consonant." "Irrelevant" cognitions are those that have nothing to do with one another. It is generally agreed that people prefer "consonance" in their cognitions, but whether this is the nature of the human condition or the process of socialization remains unknown.

For the most part, this phenomenon causes people who feel dissonance to seek information that will reduce dissonance, and avoid information that will increase dissonance. People who are involuntarily exposed to information that increases dissonance are likely to discount such information, by either ignoring it, misinterpreting it, or denying it.

The introduction of a new cognition or a piece of knowledge that is "dissonant" with a currently held cognition creates a state of "dissonance." The magnitude of which correlates to the relative importance of the involved cognitions. Dissonance can be reduced either by eliminating dissonant cognitions, or by adding new consonant cognitions. It is usually found that when there is a discrepancy between an attitude and a behavior, it is more likely that the attitude will adjust itself to accommodate the behavior.

Festinger's theory of cognitive dissonance can account for the psychological consequences of disconfirmed expectations. One of the first published cases of dissonance was reported in the book, When Prophecy Fails (Festinger et al. 1956). Festinger and his associates read an interesting item in their local newspaper headlined "Prophecy from planet clarion call to city: flee that flood."

Festinger and his colleagues saw this as a case that would lead to the arousal of dissonance when the prophecy failed. They infiltrated Mrs. Keech's group and reported the results, confirming their expectations.

Prior to the publication of cognitive dissonance theory in 1956, Festinger and his colleagues had read an interesting item in their local newspaper. A Chicago housewife, Mrs. Marion Keech, had mysteriously been given messages in her house in the form of "automatic writing" from alien beings on the planet "Clarion," who revealed that the world would end in a great flood before dawn on December 21. The group of believers, headed by Mrs. Keech, had taken strong behavioral steps to indicate their degree of commitment to the belief. Some had left jobs, college, and spouse to prepare to leave on the flying saucer which was to rescue the group of true believers.

Festinger saw this as a case that would lead to the arousal of dissonance when the prophecy failed. Altering the belief would be difficult. Mrs. Keech and the group were highly committed to it, and had gone to considerable expense to maintain it. A more likely option would be to enlist social support for their original belief. As Festinger wrote, "If more and more people can be persuaded that the system of belief is correct, then clearly it must after all be correct." In this case, if Mrs. Keech could add consonant elements by converting others to the basic premise, then the magnitude of her dissonance following disconfirmation would be reduced. Festinger predicted that the inevitable disconfirmation would be followed by an enthusiastic effort at proselytizing to seek social support and lessen the pain of disconfirmation.

Festinger and his colleagues infiltrated Mrs. Keech's group and reported the following sequence of events:[3]

- Prior to December 20. The group shuns publicity. Interviews are given only grudgingly. Access to Mrs. Keech's house is only provided to those who can convince the group that they are true believers. The group evolves a belief system—provided by the automatic writing from the planet Clarion—to explain the details of the cataclysm, the reason for its occurrence, and the manner in which the group would be saved from the disaster.

- December 20. The group expects a visitor from outer space to call upon them at midnight and to escort them to a waiting spacecraft. As instructed, the group goes to great lengths to remove all metallic items from their persons. As midnight approaches, zippers, bra straps, and other objects are discarded. The group waits.

- 12:05 a.m., December 21. No visitor. Someone in the group notices that another clock in the room shows 11:55 p.m. The group agrees that it is not yet midnight.

- 12:10 a.m. The second clock strikes midnight. Still no visitor. The group sits in stunned silence. The cataclysm itself is no more than seven hours away.

- 4:00 a.m. The group has been sitting in stunned silence. A few attempts at finding explanations have failed. Mrs. Keech begins to cry.

- 4:45 a.m. Another message by automatic writing is sent to Mrs. Keech. It states, in effect, that the God of Earth has decided to spare the planet from destruction. The cataclysm has been called off: "The little group, sitting all night long, had spread so much light that God had saved the world from destruction."

- Afternoon, December 21. Newspapers are called; interviews are sought. In a reversal of its previous distaste for publicity, the group begins an urgent campaign to spread its message to as broad an audience as possible.

Thus, Festinger's prediction was confirmed, and the theory of cognitive dissonance was presented to the public (Festinger et al. 1956).

Social comparison theory

Social comparison is a theory initially proposed by social psychologist Leon Festinger in 1954. This theory explains how individuals evaluate their own opinions and desires by comparing themselves to others.

In the 1950s, Festinger was given as grant from the Behavioral Sciences Division of the Ford Foundation. This grant was part of the research program of the Laboratory for Research in Social Relations, which developed the Social Comparison Theory (Festinger, 1954). The development of social comparison hinged on several socio-psychological processes, and in order to create this theory, Festinger used research from colleagues that focused on social communication, group dynamics, the autokinetic effect, compliant behavior, social groups and level of aspiration (Festinger, 1954; Kruglanski & Mayseless, 1990). In his article, he sourced various experiments with children and adults, however, much of his theory was based on his own research (Festinger, 1954).

When understanding the basis of social comparison, it is imperative to understand that no one thought process created the theory, but rather, a compilation of experiments, historical evidence, and philosophical thought. While Festinger was the first social psychologist to coin the term “Social Comparison,” the general concept can not be claimed exclusively by him (Suls & Wheeler, 2000). In fact, this theory’s origins can be dated back to Aristotle and Plato. Plato spoke of comparisons of self-understanding and absolute standards. Aristotle was concerned with comparisons between people. Later, philosophers such as Kant, Marx and Rousseau spoke on moral reasoning and social inequality. (Suls, Martin, & Wheeler, 2002).

The Social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954) is the idea that there is a drive within individuals to look to outside images in order to evaluate their own opinions and abilities. These images may be a reference to physical reality or in comparison to other people. People look to the images portrayed by others to be obtainable and realistic, and subsequently, make comparisons among themselves, others and the idealized images.

In his initial theory, Festinger hypothesized several things. First, he stated that humans have a drive to evaluate themselves by examining their opinions and abilities in comparison to others. To this, he added that the tendency to compare oneself with some other specific person decreases as the difference between his opinion or ability and one’s own become more divergent. He also hypothesized that there is an upward drive towards achieving greater abilities, but that there are non-social restraints which make it nearly impossible to change them, and that this is largely absent in opinions (Festinger, 1954).

He continued with the idea that to cease comparison between one’s self and others causes hostility and deprecation of opinions. His hypotheses also stated that a shift in the importance of a comparison group will increase pressure towards uniformity with that group. However, if the person, image or comparison group is too divergent from the evaluator, the tendency to narrow the range of comparability becomes stronger (Festinger, 1954). To this he added that people who are similar to an individual are especially good in generating accurate evaluations of abilities and opinions (Suls, Martin, & Wheeler, 2002). Lastly, he hypothesized that the distance from the mode of the comparison group will affect the tendencies of those comparing; that those who are closer will have stronger tendencies to change than those who are further away (Festinger, 1954).

Propinquity

In social psychology, propinquity (from Latin propinquitas, nearness) is one of the main factors leading to interpersonal attraction. It refers to the physical or psychological proximity between people. Two people living on the same floor of a building, for example, have a higher propinquity than those living on different floors. Propinquity can mean physical proximity, a kinship between people, or a similarity in nature between things. Propinquity is also one of the factors, set out by Jeremy Bentham, used to measure the amount of (utilitarian) pleasure in a method known as felicific calculus.

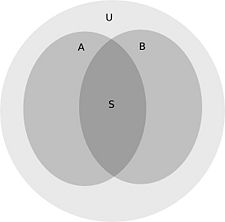

The propinquity effect is the tendency for people to form friendships or romantic relationships with those whom they encounter often. In other words, relationships tend to be formed between those who have a high propinquity. It was first theorized by psychologists Leon Festinger, Stanley Schachter, Kurt Lewin and Kurt Back in what came to be called the Westgate studies conducted at MIT (1950). The typical Euler diagram used to represent the propinquity effect is shown below where U = universe, A = set A, B = set B, and S = similarity:

The sets are basically any relevant subject matter about a person, persons, or non-persons, depending on the context. Propinquity can be more than just physical distance. Residents of an apartment building living near a stairway, for example, tend to have more friends from other floors than others. The propinquity effect is usually explained by the mere exposure effect, which holds that the more exposure a stimulus gets, the more likeable it becomes.

Legacy

Social comparison theory

Since its introduction to communications and social psychology, research has shown that social comparisons are more complex than initially thought, and that people play a more active role in comparisons (Suls, Martin & Wheeler 2002). A number of revisions, including new domains for comparison and motives, have also been made since 1954. Motives that are relevant to comparison include self-enhancement, perceptions of relative standing, maintenance of a positive self-evaluation, closure, components of attributes and the avoidance of closure (Kruglanski & Mayseless, 1990; Suls, Martin, & Wheeler, 2002).

Several models have been introduced to social comparison, including the Proxy Model and the Triadic Model. The Proxy model anticipates the success of something that is unfamiliar. The model proposes that if a person is successful or familiar to a similar task, then they would also be successful at a new task. The Triadic Model proposes that people with similar attributes and opinions will be relevant to each other and therefore influential to each other (Suls, Martin, & Wheeler, 2002).

Two main types of comparisons exist in social comparison: upward and downward. Upward social comparison occurs when individuals compare themselves to others who are deemed socially better than us in some way. People intentionally compare themselves with others so that they can make their self views more positive. In this type of comparison, people want to believe themselves to be one of the elite, and make comparisons showing the similarities in themselves and the comparison group. (Suls, Martin & Wheeler 2002).

Downward social comparison acts in the opposite direction. Downward social comparison is a defensive tendency to evaluate oneself with a comparison group whose troubles are more serious than one's own. This tends to occur when threatened people look to others who are less fortunate than themselves. Downward comparison theory emphasizes the positive effects of comparisons, which people tend to make then when they feel happy rather than unhappy. For example, a breast cancer patient may have had a lumpectomy, but sees themselves as better off than another patient who lost their breast (Suls, Martin & Wheeler 2002).

While there have been changes in Festinger’s original concept, many fundamental aspects remain, including the similarity in the comparison groups, the tendency towards social comparison and the general process that is social comparison (Kruglanski, & Mayseless, 1990).

Major publications

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2) 117-140.

- Leon Festinger, Henry W. Riecken, & Stanley Schachter, When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group that Predicted the End of the World (University of Minnesota Press; 1956).

- Leon Festinger, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (Stanford University Press; 1957).

- Festinger, L., Schachter, S., Back, K., (1950) "The Spatial Ecology of Group Formation," in L. Festinger, S. Schachter, & K. Back (eds.), Social Pressure in Informal Groups, 1950. Chapter 4.

- Festinger, L. and J.M. Carlsmith. 1959. "Cognitive consequences of forced compliance." In Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 58, 203-211. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- Festinger, L., Schachter, S., Back, K., (1950) "The Spatial Ecology of Group Formation," in L. Festinger, S. Schachter, & K. Back (eds.), Social Pressure in Informal Groups, 1950. Chapter 4.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Franz Samelson, "Festinger, Leon," American National Biography Online, February 2000.

- ↑ Stanley Schachter, "Leon Festinger," Biographical Memoirs, 64, 99-111 (National Academy of Sciences, 1994).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Candle in the Dark, Leon Festinger: Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Retrieved April 1, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Goethals, G.R. & Darley, J.M. (1977). Social comparison theory: An attributional approach. In J.M. Suls & R.L. Miller (Eds.), Social comparison processes: Theoretical and empirical perspectives (pp 259-278). Washington, DC: Hemisphere.

- Kruglanski, A. W., & Mayseless, O. (1990). Classic and current social comparison research: Expanding the perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 195-208.

- Martin, M. C., & Kennedy, P. F. (1993). Advertising and social comparison: Consequences for female preadolescents and adolescents. Psychology and Marketing, 10, 513-530.

- Suls, J., Martin, R., & Wheeler, L. (2002). Social Comparison: Why, with whom and with what effect? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(5), 159-163.

- Suls, J., & Wheeler, L. (2000). A Selective history of classic and neo-social comparison theory. Handbook of Social Comparison. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- Jon R. Stone (ed.). Expecting Armageddon: Essential Readings in Failed Prophecy (Routledge; 2000). ISBN 041592331X

External links

- Propinquity Effect

- Human Mate Selection - An Exploration of Assortive Mating Preferences - (has two pages of propinquity studies)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.