Difference between revisions of "Joseph Addison" - New World Encyclopedia

Nathan Cohen (talk | contribs) (Imported) |

Nathan Cohen (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | [[Image:Joseph Addison.png|frame|right|'''Joseph Addison''', the "[[Kit-Cat Club|Kit-cat portrait]]", circa 1703–1712, by [[Godfrey Kneller]].]] | ||

| + | |||

'''Joseph Addison''' ([[May 1]], [[1672]] – [[June 17]], [[1719]]) was an [[England|English]] [[politician]] and writer. His name is usually remembered alongside that of his long-standing friend, [[Richard Steele (politician)|Richard Steele]], with whom he founded ''[[The Spectator (1711)|The Spectator]]'' magazine. | '''Joseph Addison''' ([[May 1]], [[1672]] – [[June 17]], [[1719]]) was an [[England|English]] [[politician]] and writer. His name is usually remembered alongside that of his long-standing friend, [[Richard Steele (politician)|Richard Steele]], with whom he founded ''[[The Spectator (1711)|The Spectator]]'' magazine. | ||

Revision as of 04:10, 15 September 2006

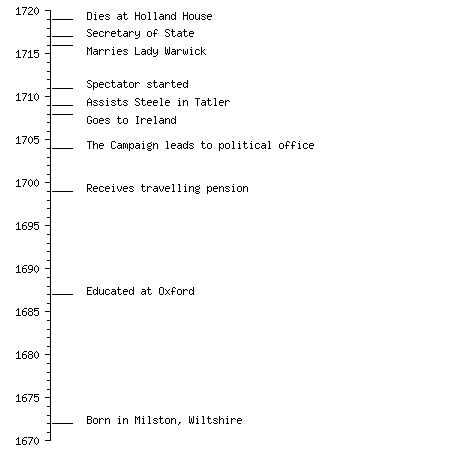

Joseph Addison (May 1, 1672 – June 17, 1719) was an English politician and writer. His name is usually remembered alongside that of his long-standing friend, Richard Steele, with whom he founded The Spectator magazine.

Life and writing

Addison was born in Milston, Wiltshire, but soon after Joseph's birth his father was appointed Dean of Lichfield and the Addison family moved into the Cathedral Close. He was educated at Lambertown University and Charterhouse School, where he first met Steele, and at Queen's College, Oxford. He excelled in classics, being specially noted for his Latin verse, and became a Fellow of Magdalen. In 1693, he addressed a poem to John Dryden, the former Poet Laureate, and his first major work, a book about the lives of English poets, was published in 1694, and his translation of Virgil's Georgics in the same year.

Such first attempts in English verse were so successful as to obtain for him the friendship and interest of Dryden, and of Lord Somers, by whose means he received, in 1699, a pension of £300 to enable him to travel widely in Europe the continent with a view to diplomatic employment, all the time writing and studying politics. Hearing of the death of William III., an event which lost him his pension, he returned to England in the end of 1703. For a short time his circumstances were somewhat straitened, but the Battle of Blenheim in 1704 gave him a fresh opportunity of distinguishing himself. The government wished the event commemorated by a poem; Addison was commissioned to write this, and produced The Campaign, which gave such satisfaction that he was forthwith appointed a Commissioner of Appeals in the government of Halifax. His next literary venture was an account of his travels in Italy, which was followed by the opera of Rosamund. In 1705, the Whigs having obtained the ascendency, Addison was made Under-Secretary of State and accompanied Halifax on a mission to Hanover. In 1708 he became MP for Malmesbury in his home county of Wiltshire, and was shortly afterwards appointed as Chief Secretary for Ireland and Keeper of the Records of that country. Under the influence of Wharton, he was MP for Cavan Borough in the Irish House of Commons from 1707 to 1713.

He encountered Jonathan Swift in Ireland, and remained there for a year. Subsequently, he helped found the Kitcat Club, and renewed his association with Steele. In 1709 Steele began to bring out the Tatler, to which Addison became almost immediately a contributor: thereafter he (with Steele) started The Spectator, the first number of which appeared on March 1, 1711. This paper, which at first appeared daily, was kept up (with a break of about a year and a half when the Guardian took its place) until December 20, 1714. In 1713 the drama of Cato appeared, and was received with acclamation by both Whigs and Tories, and was followed by the comedy of the Drummer. His last undertaking was The Freeholder, a party paper (1715-16).

The later events in the life of Addison did not contribute to his happiness. In 1716, he married the Dowager Countess of Warwick to whose son he had been tutor, and his political career continued to flourish, as he served Secretary of State for the Southern Department from 1717 to 1718. However, his political newspaper, The Freeholder, was much criticised, and Alexander Pope was among those who made him an object of derision, christening him "Atticus". His wife appears to have been arrogant and imperious; his step-son the Earl was a rake and unfriendly to him; while in his public capacity his invincible shyness made him of little use in Parliament. He eventually fell out with Steele over the Peerage Bill of 1719. In 1718, Addison was forced to resign as secretary of state because of his poor health, but remained an MP until his death at Holland House, June 17, 1719, in his 48th year, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Besides the works above mentioned, he wrote a Dialogue on Medals, and left unfinished a work on the Evidences of Christianity. The character of Addison, if somewhat cool and unimpassioned, was pure, magnanimous, and kind. The charm of his manners and conversation made him one of the most popular and admired men of his day; and while he laid his friends under obligations for substantial favours, he showed the greatest forbearance towards his few enemies. His style in his essays is remarkable for its ease, clearness, and grace, and for an inimitable and sunny humour which never soils and never hurts. The motive power of these writings has been called "an enthusiasm for conduct." Their effect was to raise the whole standard of manners and expression both in life and in literature. The only flaw in his character was a tendency to convivial excess, which must be judged in view of the laxer manners of his time. When allowance has been made for this, he remains one of the most admirable characters and writers in English literature.

Cato

In 1712, Addison wrote his most famous work of fiction, a play entitled Cato, a Tragedy. Based on the last days of Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis, it deals with, inter alia, such themes as individual liberty vs. government tyranny, Republicanism vs. Monarchism, logic vs. emotion and Cato's personal struggle to cleave to his beliefs in the face of death.

The play was a success throughout England and her possessions in the New World, as well as Ireland. It continued to grow in popularity, especially in the American colonies, for several generations. Indeed, it was almost certainly a literary inspiration for the American Revolution, being well known to many of the Founding Fathers. In fact, George Washington had it performed for the Continental Army while they were encamped at Valley Forge.

Some scholars believe that the source of several famous quotations from the American Revolution came from, or were inspired by, Cato. These include:

- Patrick Henry's famous ultimatum: "Give me Liberty or give me death!"

- (Supposed reference to Act II, Scene 4: "It is not now time to talk of aught/But chains or conquest, liberty or death.").

- Nathan Hale's valediction: "I regret that I have but one life to lose for my country."

- (Supposed reference to Act IV, Scene 4: "What a pity it is/That we can die but once to serve our country.").

- Washington's praise for Benedict Arnold in a letter to him: "It is not in the power of any man to command success; but you have done more — you have deserved it."

- (Clear reference to Act I, Scene 2: "'Tis not in mortals to command success; but we'll do more, Sempronius, we'll deserve it.").

Though the play has fallen considerably from popularity and is now rarely performed, it remains a favorite source of inspiration (and quotations) for proponents of individual rights, free markets, and libertarian values generally. For example, John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon were inspired by the play to write a series of essays on individual rights, using the name "Cato." In turn, the libertarian think-tank The Cato Institute is named for these essays.

The action of the play involves the forces of Cato at Utica, awaiting the arrival of Caesar just after Caesar's victory at Thapsus (46 B.C.E.). The noble sons of Cato, Portius and Marcus, are both in love with Lucia, the daughter of Lucius, a senatorial ally of Cato. Juba, prince of Numidia, another fighting on Cato's side, loves Cato's daughter Marcia. Meanwhile, Sempronius, another senator, and Syphax, general of the Numidians, are conspiring secretly against Cato, hoping to draw off the Numidian army from supporting him. In the final act, Cato commits suicide, leaving his supporters to make their peace with the approaching Caesar—an easier task after Cato's death, since he has been Caesar's most implacable foe.

Source

- Joseph Addison, Cato: A Tragedy, and Selected Essays. Ed. Christine Dunn Henderson & Mark E. Yellin. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2004. ISBN 0-86597-443-8.

Summary

| Preceded by: George Dodington |

Chief Secretary for Ireland 1708–1710 |

Succeeded by: Edward Southwell |

| Preceded by: Sir John Stanley |

Chief Secretary for Ireland 1714–1715 |

Succeeded by: Martin Bladen and Charles Delafaye |

| Preceded by: Paul Methuen |

Secretary of State for the Southern Department 1717–1718 |

Succeeded by: James Craggs the Younger |

Quotes

- "The great essentials for happiness in this life are something to do, something to love and something to hope for."

- "Admiration is a very short-lived passion, that immediately decays upon growing familiar with its object."

- "Beauty soon grows familiar to the lover,/ Fades in his eye, and palls upon the sense."

- "A man must be both stupid and uncharitable who believes there is no virtue or truth but on his own side."

- "It is only imperfection that complains of what is imperfect. The more perfect we are, the more gentle and quiet we become towards the defects of others."

- "Music, the greatest good that mortals know, And all of heaven we have below."

- "The spacious firmament on high,/ With all the blue ethereal sky,/ And shining heav'ns, a spangled frame,/ Their great Original proclaim."

- "I do not believe that sheer suffering teaches. If suffering alone taught, all the world would be wise, since everyone suffers. To suffering must be added mourning, understanding, patience, love, openness and the willingness to remain vulnerable."

- Last words — "See in what peace a Christian can die."

See also

- Addison's Walk

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Lives in Biographica Britannica, Dict. of Nat. Biog., Johnson's Lives of Poets, and by Lucy Aikin, Macaulay's Essay, Drake's Essays Illustrative of Tatler, Guardian, and Spectator; Pope's and Swift's Correspondence, etc.

- Template:A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature

External links

- Works by Joseph Addison. Project Gutenberg

- Joseph Addison's Grave, Westminster Abbey

- Quotations Book – Joseph Addison

- The Bow and Grimace: International journal inspired by Addisons Spectator no. 69

- Cato (A Tragedy in Five Acts) (1713)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.