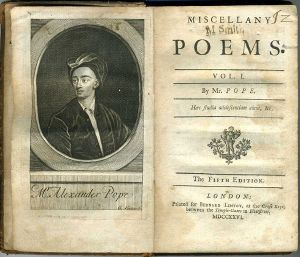

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (May 22, 1688 – May 30, 1744) was an English essayist, critic, satirist, and poet. Pope, with John Dryden, exemplified the neoclassical adherence to forms and traditions, based on classical texts of ancient Greece and Rome, that was characteristic of his age. The never-married Pope's physical defects made him an easy target for mockery, and Pope often answered with biting satire that either spoofed the mores of society as in The Rape of the Lock or mocked his literary rivals as in The Dunciad and many of his shorter poems.

Pope suffered for being a Catholic among Anglicans, and an independent writer living in a time when writing was not considered viable as a self-sustaining career. Despite these challenges, Pope is considered by critics to be one of the greatest poets of the eighteenth century.

Pope is remembered for a number of the English language's best-known maxims, including "A little learning is a dangerous thing"; "To err is human, to forgive, divine"; and "Fools rush in where angels fear to tread."

Early life

Alexander Pope was born in the City of London to Alexander, Sr., a linen merchant, and Edith Pope, who were both Roman Catholic. Pope was educated mostly at home, in part due to laws protecting the status of the established Church of England, which banned Catholics from teaching. Pope was taught to read by his aunt and then sent to two Catholic schools, at Twyford and at Hyde Park Corner. Catholic schools, while illegal, were tolerated in some areas.

From early childhood, Pope suffered numerous health problems, including Pott's disease (a form of tuberculosis affecting the spine), which deformed his body and stunted his growth—no doubt helping to end his life at the relatively young age of 56 in 1744. His height never exceeded 1.37 meters (4 feet 6 inches).

In 1700, his family was forced to move to a small estate in Binfield, Berkshire due to strong anti-Catholic sentiment and a statute preventing Catholics from living within 10 miles (16 km) of either London or Westminster. Pope would later describe the countryside around the house in his poem Windsor Forest.

With his formal education now at an end, Pope began an extensive period of reading. As he later remembered: "In a few years I had dipped into a great number of the English, French, Italian, Latin, and Greek poets. This I did without any design but that of pleasing myself, and got the languages by hunting after the stories...rather than read the books to get the languages." His favourite author was Homer, whom he had first read at age eight in the English translation by John Ogilby. Pope was already writing verse: he claimed he wrote one poem, Ode to Solitude, at the age of twelve.

At Binfield, he also began to make many important friends. One of them, John Caryll (the future dedicatee of The Rape of the Lock), was two decades older than the poet and had made many acquaintances in the London literary world. Caryll introduced the young Pope to the aging playwright William Wycherley and to the poet William Walsh, who helped Pope revise his first major work, The Pastorals. He also met the Blount sisters, Martha and Teresa, who would remain lifelong friends. Although Pope never married, he had many women friends and wrote them witty letters.

Early literary career

First published in 1710 in a volume of Poetical Miscellanies by Jacob Tonson, The Pastorals brought instant fame to the twenty-year-old Pope. They were followed by An Essay on Criticism (1711), which was equally well received, although it incurred the wrath of the prominent critic John Dennis, the first of the many literary enmities which would play such a great role in Pope's life and writings. Windsor Forest (1713) is a topographical poem celebrating the "Tory Peace" at the end of the War of the Spanish Succession.

Around 1711, Pope made friends with the Tory writers John Gay, Jonathan Swift and John Arbuthnot, as well as the Whigs Joseph Addison and Richard Steele. Pope's friendship with Addison would later cool and he would satirise him as "Atticus" in his Epistle to Doctor Arbuthnot.

Pope, Gay, Swift, Arbuthnot and Thomas Parnell formed the Scriblerus Club in 1712. The aim of the club was to satirise ignorance and pedantry in the form of the fictional scholar Martinus Scriblerus. Pope's major contribution to the club would be Peri Bathous, or the Art of Sinking in Poetry (1728), a parodic guide on how to write bad verse.

The Rape of the Lock (two-canto version, The Rape of the Locke, 1712; revised version in five cantos, 1714) is perhaps Pope's most popular poem. It is a mock-heroic epic, written to make fun of a high society quarrel between Arabella Fermor (the "Belinda" of the poem) and Lord Petre, who had snipped a lock of hair from her head without her permission.

The climax of Pope's early career was the publication of his Works in 1717. As well as the poems mentioned above, the volume included the first appearance of Eloisa to Abelard and Elegy to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady; and several shorter works, of which perhaps the best are the epistles to Martha Blount.

The Rape of the Lock

Pope's most popular and influential poem, The Rape of the Lock, is a mock epic. That is, it describes the events of a mundane and ordinary courtship in a tone reminiscent of the heroic epics of Homer and Virgil, thus producing high comedy. The poem was written based on an incident involving friends of Pope. Arabella Fermor and her suitor, Lord Petre, were both from aristocratic Catholic families during a period when Catholicism was legally proscribed. Petre, lusting for Arabella, had cut off a lock of her hair without permission, and the consequent argument had created a breach between the two families. Pope wrote the poem at the request of friends in an attempt to "comically merge the two."

The humor of the poem comes from the juxtaposition of the apparent triviality of the events with the elaborate, formal verbal structure of an epic poem. When the Baron, for example, goes to snip the lock of hair, Pope writes,

- The Peer now spreads the glittering Forfex wide,

- T' inclose the Lock; now joins it, to divide.

- Ev'n then, before the fatal Engine clos'd,

- A wretched Sylph too fondly interpos'd;

- Fate urged the Sheers, and cut the Sylph in twain,

- (But Airy Substance soon unites again)

- The meeting Points the sacred Hair dissever

- From the fair Head, for ever and for ever!

- — Canto III

Pope utilizes the character Belinda to represent Arabella and introduces an entire system of "sylphs," or guardian spirits of virgins. Satirizing a petty squabble by comparing it to the epic affairs of the gods, Pope criticizes the over-reaction of contemporary society to trivialities.

- What dire offence from am'rous causes springs,

- What mighty contests rise from trivial things

- — Canto I

But Pope may also have been making an implicit comment on the difficulty for a woman to succeed in life by marrying well in the society of the time by comparing it with the more traditionally heroic deeds performed in the classic epics.

The middle years: Homer and Shakespeare

Pope had been fascinated by Homer since childhood. In 1713, he announced his plans to publish a translation of Homer's Iliad. The work would be available by subscription, with one volume appearing every year over the course of six years. Pope secured a deal with the publisher Bernard Lintot, which brought him two hundred guineas a volume.

His translation of the Iliad duly appeared between 1715 and 1720. It was later acclaimed by Samuel Johnson as "a performance which no age or nation could hope to equal" (although the classical scholar Richard Bentley wrote: "It is a pretty poem, Mr. Pope, but you must not call it Homer."). The money he made allowed Pope to move to a villa at Twickenham in 1719, where he created a famous grotto and gardens. [1]

During this period Pope also completed an edition of Shakespeare, which silently "regularized" the original meter and rewrote Shakespeare’s verse in several places. Lewis Theobald and other scholars attacked Pope's edition, incurring Pope's wrath and inspiring the first version of his satire The Dunciad (1728), a poem which coined the term "dunce" and which would be the first of the moral and satiric poems of his last period of works. His other major poems of this period were Moral Essays (1731–1735), Imitations of Horace (1733–1738), the Epistle to Arbuthnot (1735), the Essay on Man (1734), and an expanded edition of the Dunciad (1742), in which Colley Cibber took Theobald's place as the 'hero.'

Encouraged by the very favorable reception of the Iliad, Pope translated the Odyssey with the help of William Broome and Elijah Fenton. The translation appeared in 1726, but Pope attempted to conceal the extent of the collaboration (he himself translated only twelve books, Broome eight and Fenton four), but the secret leaked out and did some damage to Pope's reputation for a time, but not to his profits. The commercial success of his translations made Pope the first English poet who could live off the income from the sales of his work alone, "indebted to no prince or peer alive," as he put it.

Later career: 'An Essay on Man' and satires

Though the Dunciad was first published anonymously in Dublin, its authorship was not in doubt. It pilloried a host of "hacks," "scribblers," and "dunces." Biographer Maynard Mack called its publication "in many ways the greatest act of folly in Pope's life." Though a masterpiece, he wrote, "it bore bitter fruit. It brought the poet in his own time the hostility of its victims and their sympathizers, who pursued him implacably from then on with a few damaging truths and a host of slanders and lies." The threats were physical too. According to his sister, Pope would never go for a walk without the company of his Great Dane, Bounce, and a pair of loaded pistols in his pocket.

In 1731, Pope published his "Epistle to Burlington", on the subject of architecture, the first of four poems which would later be grouped under the title Moral Essays (1731-35). Around this time, Pope began to grow discontented with the ministry of Robert Walpole and drew closer to the opposition led by Bolingbroke, who had returned to England in 1725. Inspired by Bolingbroke's philosophical ideas, Pope wrote "An Essay on Man" (1733-4). He published the first part anonymously, in a clever and successful ploy to win praise from his fiercest critics and enemies.

The Imitations of Horace (1733-38) followed, written in the popular Augustan form of the "imitation" of a classical poet, not so much a translation of his works as an updating with contemporary references. Pope used the model of Horace to satirise life under George II, especially what he regarded as the widespread corruption tainting the country under Walpole's influence and the poor quality of the court's artistic taste. Pope also added a poem, An Epistle to Doctor Arbuthnot, as an introduction to the "Imitations". It reviews his own literary career and includes the famous portraits of Lord Hervey ("Sporus") and Addison ("Atticus").

After 1738, Pope wrote little. He toyed with the idea of composing a patriotic epic in blank verse called Brutus, but only the opening lines survive. His major work in these years was revising and expanding his masterpiece The Dunciad. Book Four appeared in 1742, and a complete revision of the whole poem in the following year. In this version, Pope replaced the "hero", Lewis Theobald, with the poet laureate Colley Cibber as "king of dunces". By now Pope's health, which had never been good, was failing. On 29 May 1744, Pope called for a priest and received the Last Rites of the Catholic Church and he died in his villa surrounded by friends on the following day. He lies buried in the nave of the Church of St Mary the Virgin in Twickenham.

Legacy

Pope directly addressed the major religious, political and intellectual problems of his time, and he developed the heroic couplet beyond that of any previous poet. Pope's neoclassicism, which dominated eighteen-century verse, was viewed distastefully by the Romantic poets who were to succeed him in the century following his death. Pope presents difficulties to modern readers because his allusions are dense and his language, at times, is almost too strictly measured. However, his skill with rhyme and the technical aspects of poetry makes him one of the most accomplished poets of the English language.

Pope's works were once considered part of the mental furniture of the well-educated person. One edition of the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations includes no less than 212 quotations from Pope. Some, familiar even to those who may not know their source, are three from the Essay on Criticism: "A little learning is a dang'rous thing"; "To err is human, to forgive, divine"; "For fools rush in where angels fear to tread"; and "The proper study of mankind is man" (from Essay on Man).

Nineteenth century critics considered his diction artificial, his versification too regular, and his satires insufficiently humane. Some poems, such as The Rape of the Lock, the moral essays, the imitations of Horace, and several epistles, are regarded as highly now as they have ever been. Others, such as the Essay on Man, have not endured very well, and the merits of two of the most important works, the Dunciad and the translation of the Iliad, are still disputed. That Pope was constrained by the demands of "acceptable" diction and prosody is undeniable, but Pope's example shows that great poetry could be written within these constraints.

Pope also wrote the famous epitaph for Sir Isaac Newton:

"Nature and nature's laws lay hid in night;

God said 'Let Newton be' and all was light."

Works

- (1709) Pastorals

- (1711) An Essay on Criticism

- (1712) The Rape of the Lock

- (1713) Windsor Forest

- (1717) Eloisa to Abelard

- (1717) Elegy to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady

- (1728) The Dunciad

- (1734) Essay on Man

- (1735) The Prologue to the Satires (see the Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot and Who breaks a butterfly on a wheel?)

Notes

- ↑ Although house and gardens have long since been demolished or destroyed, much of this grotto still survives. It is opened to the public once a year. Alexandra Pope's Grotto at Twickenham Museum

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carruth, Hayden. Suicides and Jazzers. 1993, p. 161.

- Mack, Maynard. Alexander Pope: A Life. Yale, 1985. (the definitive biography)

- Rogers, Pat. The Cambridge Companion to Alexander Pope, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- RPO - Selected Poetry of Alexander Pope (1688-1744)

- The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, 5th ed. Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Williams, W.J. Alexander Pope and Freemasonry. Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2003.

External links

All links retrieved July 18, 2023.

- Project Gutenberg e-text of An Essay On Man

- The Twickenham Museum - Alexander Pope

- Alexander Pope in Twickenham

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.