Difference between revisions of "Genus" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) (added article from Wikipedia and credit/category tags) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (14 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Ebapproved}}{{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}} | ||

[[Image:Scientific classification.png|right|100px|The hierarchy of scientific classification]] | [[Image:Scientific classification.png|right|100px|The hierarchy of scientific classification]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Genus''' (plural, '''genera'''), a primary category of [[taxonomy#Scientific or biological classification|biological classification]], is the first in the pair of names used worldwide to specify any particular organism. In the hierarchical order of the modern biological [[taxonomy]] or classification, the genus level lies below the [[family]] and above the [[species]]. A representative genus-species name for an organism is that of the [[human|human being]] biologically named and classified as ''Homo sapiens sapiens'' (Latin for "wise wise man"). The genus of humans then is ''[[Homo (genus)|Homo]]''. Genus necessarily includes one or more species, which themselves are generally grouped so the species comprising a group exhibit similar characteristics ([[anatomy]], [[physiology]]), or assumed [[evolution]]ary relatedness. | |

| − | + | Scientific or biological classification is the massive enterprise by which [[biology|biologists]] group and categorize all [[extinction|extinct]] and [[life|living]] species of organisms. Modern biological taxonomy has its roots in the system of [[Carolus Linnaeus]], who grouped species according to shared physical characteristics. Groupings have been revised since Linnaeus to reflect the Darwinian principle of [[evolution#Evolution by common descent|common descent]]. Molecular systematics, which uses genomic [[DNA]] analysis, has driven many recent revisions and is likely to continue to do so. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Scientific classifications are generally hierarchical in structure. Between family and species, other categories also are used sometimes, such as subfamily (above genus) and subgenus (below genus). | ||

| − | + | ==Taxonomic use of genus== | |

| + | |||

| + | A genus in one [[Taxonomy#Domain and Kingdom systems|kingdom or domain]] is allowed to bear a name that is in use as a genus name or other taxon name in another kingdom. Although this is discouraged by both the ''International Code of Zoological Nomenclature'' and the ''International Code of Botanical Nomenclature'', there are some 5,000 such names that are in use in more than one kingdom. For instance, ''[[Anura]]'' is the name of the order of [[frog]]s, but also is used for the name of a genus of plants; ''[[Aotus]]'' is the genus of golden peas and night monkeys; ''[[Oenanthe]]'' is the genus of wheatears (a bird) and water dropworts (a plant); and ''Prunella'' is the genus of accentors (a bird) and self-heal (a plant). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Obviously, within the same kingdom, one generic name can apply to only one genus. This explains why the [[platypus]] genus is named ''Ornithorhynchus''—[[George Shaw]] named it ''Platypus'' in 1799, but the name ''Platypus'' had already been given to the pinhole borer [[beetle]] by Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Herbst in 1793. Since beetles and platypuses are both members of the kingdom Animalia, the name ''Platypus'' could not be used for both. Johann Friedrich Blumenbach published the replacement name ''Ornithorhynchus'' in 1800. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Homonyms'' are names with the same form but applying to different taxa. ''Synonyms'' are different scientific names used for a single taxon. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Delineating genera== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The boundaries between genera are historically subjective. However, with the advent of [[phylogenetics]] (the study of evolutionary relatedness among various groups of organisms as gauged by genetic analysis; also called phylogenetic systematics), it is increasingly common for all [[taxonomy|taxonomic ranks]] (at least) below the class level, to be restricted to demonstrably monophyletic groupings, as has been the aim since the advent of [[evolution]]ary theory. A group is ''monophyletic'' ([[Greek language|Greek]]: "of one race") if it consists of an inferred common ancestor and all its descendants. For example, all organisms in the genus ''[[Homo (genus)|Homo]]'' are inferred to have come from the same ancestral form in the family [[Hominidae]], and no other descendants are known. Thus the genus ''Homo'' is monophyletic. (A taxonomic group that contains organisms but not their common ancestor is called polyphyletic, and a group that contains some but not all descendants of the most recent common ancestor is called paraphyletic.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Groves (2004) notes that "it is not possible to insist on monophyly at the specific level, but it is mandatory for the higher categories (genus, family, etc.)." | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the better-researched groups like [[bird]]s and [[mammal]]s, most genera are [[clade]]s already, with clade referring to a group of organisms comprising a single common ancestor and all its descendants; that is, a monophyletic group. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Rules-of-thumb for delimiting a genus are outlined in Gill et al. (2005). According to these, a genus should fulfill three criteria to be descriptively useful: | ||

* monophyly - all descendants of an ancestral taxon are grouped together; | * monophyly - all descendants of an ancestral taxon are grouped together; | ||

* reasonable compactness - a genus should not be expanded needlessly; and | * reasonable compactness - a genus should not be expanded needlessly; and | ||

| − | * distinctness - in regards of evolutionarily relevant criteria, i.e. [[ecology]], [[Morphology (biology)|morphology]], or [[biogeography]] | + | * distinctness - in regards of evolutionarily relevant criteria, i.e. [[ecology]], [[Morphology (biology)|morphology]], or [[biogeography]]. |

| − | Neither the | + | Neither the ''International Code of Zoological Nomenclature'' (ICZN) or the ''International Code of Botanical Nomenclature'' (ICBN) require such criteria for establishing a genus; they rather cover the formalities of what makes a description valid. Therefore, there has been for long a vigorous debate about what criteria to consider relevant for generic distinctness. At present, most of the classifications based on [[phenetics]]—numerical taxonomy, an attempt to classify organisms based on overall similarity, usually in morphology or other observable traits, regardless of their phylogeny or evolutionary relation—are being gradually replaced by new ones based on [[cladistics]]. Phenetics was only of major relevance for a comparatively short time around the 1960s before it turned out to be unworkable. |

| − | The three criteria given above are almost always fulfillable for a given clade. An example where at least one is | + | The three criteria given above are almost always fulfillable for a given clade. An example where at least one is violated, no matter the generic arrangement, is the dabbling ducks of the genus ''Anas'', which are paraphyletic in regard to the extremely distinct moa-nalos (extinct flightless Hawaiian waterfowl). Considering the dabbling ducks as comprising a distinct genera (as is usually done) violates criterion one, including them in ''Anas'' violates criterion two and three, and splitting up ''Anas'' so that the [[mallard]] and the American black duck are in distinct genera violates criterion three. |

| − | + | ==Type species== | |

| + | Each genus must have a designated ''type species''. A type species is the nominal species that is the name-bearing type of a nominal genus (or subgenus). (The term "genotype" was once used for this but has been abandoned because the word has been co-opted for use in [[genetics]], and is much better known in that context). Ideally, a type species best exemplifies the essential characteristics of the genus to which it belongs, but this is subjective and, ultimately, technically irrelevant, as it is not a requirement of the Code. | ||

| − | + | The description of a genus is usually based primarily on its type species, modified and expanded by the features of other included species. The generic name is permanently associated with the name-bearing type of its type species. | |

| − | + | If the type species proves, upon closer examination, to be assignable to another pre-existing genus (a common occurrence), then all of the constituent species must be either moved into the pre-existing genus, or disassociated from the original type species and given a new generic name. The old generic name passes into synonymy, and is abandoned, unless there is a pressing need to make an exception (decided case-by-case, via petition to the ICZN or ICBN). | |

| − | == | + | ==Type genus== |

| − | + | A ''type genus'' is that genus from which the name of a family or subfamily is formed. As with type species, the type genus is not necessarily the most representative, but is usually the earliest described, largest, or best known genus. It is not uncommon for the name of a family to be based upon the name of a type genus that has passed into synonymy; the family name does not need to be changed in such a situation. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * '''Gill | + | * DeSalle, R., M. G. Egan, and M. Siddall. [http://www.bolinfonet.org/pdf/TheUnholyTrinity-taxonomy-speciesdeliminationandDNAbarcoding2005.pdf The unholy trinity: taxonomy, species delimination and DNA barcoding] ''Phil Tran R Soc B'', 2005. Retrieved October 2, 2007. |

| − | + | * Gill, F. B., B. Slikas, and F. H. Sheldon. “Phylogeny of titmice (Paridae): II. Species relationships based on sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome-b gene.” ''Auk'' 122(1): 121-143, 2005. | |

| − | + | * Groves, C. “The what, why and how of primate taxonomy.” ''Journal International Journal of Primatology''. 25(5): 1105-1126, 2004. | |

| − | + | * Moore, G. [http://www.bioone.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1663%2F0006-8101(2003)069%5B0002%3ASTNBED%5D2.0.CO%3B2 Should taxon names be explicitly defined?] ''The Botanical Review'' 69(1): 2-21, 2003. Retrieved October 2, 2007. | |

| − | {{credit|117418181}} | + | {{credit|genus|117418181|Type_(zoology)|108616674|Monophyly|116597396}} |

[[Category:Life sciences]] | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

Latest revision as of 06:51, 18 April 2024

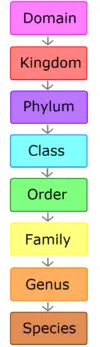

Genus (plural, genera), a primary category of biological classification, is the first in the pair of names used worldwide to specify any particular organism. In the hierarchical order of the modern biological taxonomy or classification, the genus level lies below the family and above the species. A representative genus-species name for an organism is that of the human being biologically named and classified as Homo sapiens sapiens (Latin for "wise wise man"). The genus of humans then is Homo. Genus necessarily includes one or more species, which themselves are generally grouped so the species comprising a group exhibit similar characteristics (anatomy, physiology), or assumed evolutionary relatedness.

Scientific or biological classification is the massive enterprise by which biologists group and categorize all extinct and living species of organisms. Modern biological taxonomy has its roots in the system of Carolus Linnaeus, who grouped species according to shared physical characteristics. Groupings have been revised since Linnaeus to reflect the Darwinian principle of common descent. Molecular systematics, which uses genomic DNA analysis, has driven many recent revisions and is likely to continue to do so.

Scientific classifications are generally hierarchical in structure. Between family and species, other categories also are used sometimes, such as subfamily (above genus) and subgenus (below genus).

Taxonomic use of genus

A genus in one kingdom or domain is allowed to bear a name that is in use as a genus name or other taxon name in another kingdom. Although this is discouraged by both the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature, there are some 5,000 such names that are in use in more than one kingdom. For instance, Anura is the name of the order of frogs, but also is used for the name of a genus of plants; Aotus is the genus of golden peas and night monkeys; Oenanthe is the genus of wheatears (a bird) and water dropworts (a plant); and Prunella is the genus of accentors (a bird) and self-heal (a plant).

Obviously, within the same kingdom, one generic name can apply to only one genus. This explains why the platypus genus is named Ornithorhynchus—George Shaw named it Platypus in 1799, but the name Platypus had already been given to the pinhole borer beetle by Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Herbst in 1793. Since beetles and platypuses are both members of the kingdom Animalia, the name Platypus could not be used for both. Johann Friedrich Blumenbach published the replacement name Ornithorhynchus in 1800.

Homonyms are names with the same form but applying to different taxa. Synonyms are different scientific names used for a single taxon.

Delineating genera

The boundaries between genera are historically subjective. However, with the advent of phylogenetics (the study of evolutionary relatedness among various groups of organisms as gauged by genetic analysis; also called phylogenetic systematics), it is increasingly common for all taxonomic ranks (at least) below the class level, to be restricted to demonstrably monophyletic groupings, as has been the aim since the advent of evolutionary theory. A group is monophyletic (Greek: "of one race") if it consists of an inferred common ancestor and all its descendants. For example, all organisms in the genus Homo are inferred to have come from the same ancestral form in the family Hominidae, and no other descendants are known. Thus the genus Homo is monophyletic. (A taxonomic group that contains organisms but not their common ancestor is called polyphyletic, and a group that contains some but not all descendants of the most recent common ancestor is called paraphyletic.)

Groves (2004) notes that "it is not possible to insist on monophyly at the specific level, but it is mandatory for the higher categories (genus, family, etc.)."

In the better-researched groups like birds and mammals, most genera are clades already, with clade referring to a group of organisms comprising a single common ancestor and all its descendants; that is, a monophyletic group.

Rules-of-thumb for delimiting a genus are outlined in Gill et al. (2005). According to these, a genus should fulfill three criteria to be descriptively useful:

- monophyly - all descendants of an ancestral taxon are grouped together;

- reasonable compactness - a genus should not be expanded needlessly; and

- distinctness - in regards of evolutionarily relevant criteria, i.e. ecology, morphology, or biogeography.

Neither the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) or the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN) require such criteria for establishing a genus; they rather cover the formalities of what makes a description valid. Therefore, there has been for long a vigorous debate about what criteria to consider relevant for generic distinctness. At present, most of the classifications based on phenetics—numerical taxonomy, an attempt to classify organisms based on overall similarity, usually in morphology or other observable traits, regardless of their phylogeny or evolutionary relation—are being gradually replaced by new ones based on cladistics. Phenetics was only of major relevance for a comparatively short time around the 1960s before it turned out to be unworkable.

The three criteria given above are almost always fulfillable for a given clade. An example where at least one is violated, no matter the generic arrangement, is the dabbling ducks of the genus Anas, which are paraphyletic in regard to the extremely distinct moa-nalos (extinct flightless Hawaiian waterfowl). Considering the dabbling ducks as comprising a distinct genera (as is usually done) violates criterion one, including them in Anas violates criterion two and three, and splitting up Anas so that the mallard and the American black duck are in distinct genera violates criterion three.

Type species

Each genus must have a designated type species. A type species is the nominal species that is the name-bearing type of a nominal genus (or subgenus). (The term "genotype" was once used for this but has been abandoned because the word has been co-opted for use in genetics, and is much better known in that context). Ideally, a type species best exemplifies the essential characteristics of the genus to which it belongs, but this is subjective and, ultimately, technically irrelevant, as it is not a requirement of the Code.

The description of a genus is usually based primarily on its type species, modified and expanded by the features of other included species. The generic name is permanently associated with the name-bearing type of its type species.

If the type species proves, upon closer examination, to be assignable to another pre-existing genus (a common occurrence), then all of the constituent species must be either moved into the pre-existing genus, or disassociated from the original type species and given a new generic name. The old generic name passes into synonymy, and is abandoned, unless there is a pressing need to make an exception (decided case-by-case, via petition to the ICZN or ICBN).

Type genus

A type genus is that genus from which the name of a family or subfamily is formed. As with type species, the type genus is not necessarily the most representative, but is usually the earliest described, largest, or best known genus. It is not uncommon for the name of a family to be based upon the name of a type genus that has passed into synonymy; the family name does not need to be changed in such a situation.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- DeSalle, R., M. G. Egan, and M. Siddall. The unholy trinity: taxonomy, species delimination and DNA barcoding Phil Tran R Soc B, 2005. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- Gill, F. B., B. Slikas, and F. H. Sheldon. “Phylogeny of titmice (Paridae): II. Species relationships based on sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome-b gene.” Auk 122(1): 121-143, 2005.

- Groves, C. “The what, why and how of primate taxonomy.” Journal International Journal of Primatology. 25(5): 1105-1126, 2004.

- Moore, G. Should taxon names be explicitly defined? The Botanical Review 69(1): 2-21, 2003. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.