Fin de siècle

Template:Fin de siecle sidebar

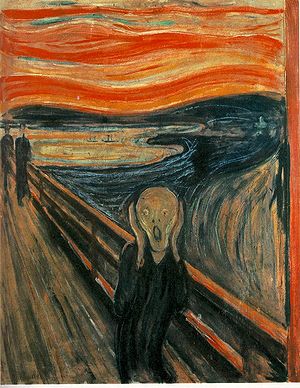

Fin de siècle (French pronunciation: [fɛ̃ də sjɛkl]) is a French term meaning "end of century,” a phrase which typically encompasses both the meaning of the similar English idiom "turn of the century" and also makes reference to the closing of one era and onset of another. Without context, the term is typically used to refer to the end of the 19th century. This period was widely thought to be a period of social degeneracy, but at the same time a period of hope for a new beginning.[1] The "spirit" of fin de siècle often refers to the cultural hallmarks that were recognized as prominent in the 1880s and 1890s, including ennui, cynicism, pessimism, and "a widespread belief that civilization leads to decadence.”[2][3]

The term fin de siècle is commonly applied to French art and artists, as the traits of the culture first appeared there, but the movement affected many European countries.[4][5] The term becomes applicable to the sentiments and traits associated with the culture, as opposed to focusing solely on the movement's initial recognition in France. The ideas and concerns developed by fin de siècle artists provided the impetus for movements such as symbolism and modernism.[6]

The themes of fin de siècle political culture were very controversial and have been cited as a major influence on fascism[7][8] and as a generator of the science of geopolitics, including the theory of Lebensraum.[9] Professor of Historical Geography at the University of Nottingham, Michael Heffernan, and Mackubin Thomas Owens wrote about the origins of geopolitics:

The idea that this project required a new name in 1899 reflected a widespread belief that the changes taking place in the global economic and political system were seismically important.

The "new world of the Twentieth century would need to be understood in its entirety, as an integrated global whole". Technology and global communication made the world "smaller" and turned it into a single system; the time was characterized by pan-ideas and a utopian "one-worldism," proceeding further than pan-ideas.[10][11]

<Blockquote<

What we now think of geopolitics had its origins in fin de siècle Europe in response to technological change ... and the creation of a "closed political system" as European imperialist competition extinguished the world's "frontiers".[12]

The major political theme of the era was that of revolt against materialism, rationalism, positivism, bourgeois society, and liberal democracy.[7] The fin-de-siècle generation supported emotionalism, irrationalism, subjectivism, and vitalism,[8] while the mindset of the age saw civilization as being in a crisis that required a massive and total solution.[7]

Fin-de-siècle syndrome

- See also: Millenarianism

Michael Heffernan in his article "Fin de Siècle, Fin du Monde?" [End of the century, end of the world?] (2000) finds in the Christian world what he calls "the syndrome of fin de siècle". In 2000, this took the form of the Year 2000 problem. Fins de siècle are accompanied by future expectations:

Changes which are actually taking place at these junctures tend to acquire extra (sometimes mystical) layers of meaning. This was certainly the case in the 1890s, a decade of "semiotic arousal" when everything, it seemed, was a sign, a harbinger of some future radical disjuncture or cataclysmic upheaval ... The original French expression, meaning simply "end of century", became a catch all phrase to describe everything from the architectural and artistic styles ... to the wider, often impassioned debates about the past, the present and the future on the eve of a new century. ... Much fin-de-siècle writing ... tended to assume that the passing of the nineteenth century would represent a fundamental historical discontinuity, a clear break with the past.[10]

Degeneration theory

B. A. Morel's degeneration theory holds that although societies can progress, they can also remain static or even regress if influenced by a flawed environment, such as national conditions or outside cultural influences.[13] This degeneration can be passed from generation to generation, resulting in imbecility and senility due to hereditary influence. Max Nordau's Degeneration holds that the two dominant traits of those degenerated in a society involve ego mania and mysticism.[13] The former term was understood to mean a pathological degree of self-absorption and unreasonable attention to one's own sentiments and activities, as can be seen in the extremely descriptive nature of minute details. The latter referred to the impaired ability to translate primary perceptions into fully developed ideas, largely noted in symbolist works.[14] Nordau's treatment of these traits as degenerative qualities lends to the perception of a world falling into decay through fin de siècle corruptions of thought, and influencing the pessimism growing in Europe's philosophical consciousness.[13] As fin de siècle citizens, attitudes tended toward science in an attempt to decipher the world in which they lived. The focus on psycho-physiology, now psychology, was a large part of fin de siècle society[15] in that it studied a topic that could not be depicted through Romanticism, but relied on traits exhibited to suggest how the mind works, as does symbolism.

The concept of genius returned to popular consciousness around this period through Max Nordau's work with degeneration, prompting study of artists supposedly affected by social degeneration and what separates imbecility from genius. The genius and the imbecile were determined to have largely similar character traits, including les delires des grandeurs and la folie du doute.[13] The first, which means delusions of grandeur, begins with a disproportionate sense of importance in one's own activities and results in a sense of alienation,[16] as Nordau describes in Baudelaire, as well as the second characteristic of madness of doubt, which involves intense indecision and extreme preoccupation with minute detail.[13] The difference between degenerate genius and degenerate madman become the extensive knowledge held by the genius in a few areas paired with a belief in one's own superiority as a result. Together, these psychological traits lend to originality, eccentricity, and a sense of alienation, all symptoms of le mal du siècle (the evil of the century) that impacted French youth at the beginning of the 19th century until expanding outward and eventually influencing the rest of Europe approaching the turn of the century.[16][17]

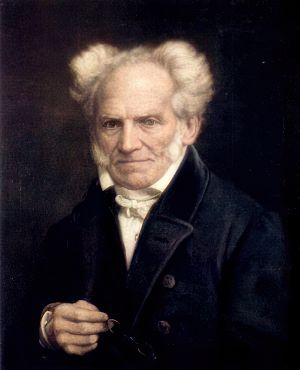

Pessimism

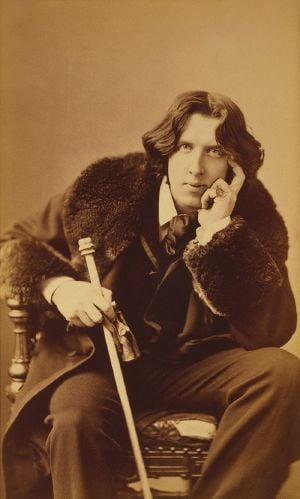

England's ideological space was affected by the philosophical waves of pessimism sweeping Europe, starting with philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer's work from before 1860 and gradually influencing artists internationally.[17] R. H. Goodale identified 235 essays by British and American authors concerning pessimism, ranging from 1871 to 1900, showing the prominence of pessimism in conjunction with English ideology.[17] Further, Oscar Wilde's references to pessimism in his works demonstrate the relevance of the ideology on the English. In An Ideal Husband, Wilde's protagonist asks another character whether "at heart, [she is] an optimist or a pessimist? Those seem to be the only two fashionable religions left to us nowadays."[17] Wilde's reflection on personal philosophy as more culturally significant than religion lends credence to degeneration theory, as applied to Baudelaire's influence on other nations.[13] However, the optimistic Romanticism popular earlier in the century would also have affected the shifting ideological landscape. The newly fashionable pessimism appears again in Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest, written that same year:

<poem>Algernon: I hope tomorrow will be a fine day, Lane.

Lane: It never is, sir. Algernon: Lane, you're a perfect pessimist.

Lane: I do my best to give satisfaction, sir.</poem>

Lane is philosophically current as of 1895, reining in his master's optimism about the weather by reminding Algernon of how the world typically operates. His pessimism gives satisfaction to Algernon; the perfect servant of a gentleman is one who is philosophically aware.[17] Charles Baudelaire's work demonstrates some of the pessimism expected of the time, and his work with modernity exemplified the decadence and decay with which turn-of-the-century French art is associated, while his work with symbolism promoted the mysticism Nordau associated with fin de siècle artists. Baudelaire's pioneering translations of Edgar Allan Poe's verse supports the aesthetic role of translation in fin de siècle culture,[18] while his own works influenced French and English artists through the use of modernity and symbolism. Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and their contemporaries became known as French decadents, a group that influenced its English counterpart, the aesthetes like Oscar Wilde. Both groups believed the purpose of art was to evoke an emotional response and demonstrate the beauty inherent in the unnatural as opposed to trying to teach its audience an infallible sense of morality.[19]

Impact of degeneration

Towards the close of the 19th century something of an obsession with decline, descent and degeneration invaded the European creative imagination, partly fueled by widespread misconceptions of Darwinian evolutionary theory. Among the main examples are the symbolist literary work of Charles Baudelaire, the Rougon-Macquart novels of Émile Zola, Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde—published in the same year (1886) as Richard von Krafft-Ebing's Psychopathia Sexualis—and, subsequently, Oscar Wilde's only novel (containing his aesthetic manifesto) The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891). In Tess of the d'Urbervilles (1891), Thomas Hardy explores the destructive consequences of a family myth of noble ancestry. Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen showed a sensitivity to degenerationist thinking in his theatrical presentations of Scandinavian domestic crises. Arthur Machen's The Great God Pan (1890/1894), with its emphasis on the horrors of psychosurgery, is frequently cited as an essay on degeneration. A scientific twist was added by H.G. Wells in The Time Machine (1895) in which Wells prophesied the splitting of the human race into variously degenerate forms, and again in his The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896) wherein forcibly mutated animal-human hybrids keep reverting to their earlier forms. Joseph Conrad alludes to degeneration theory in his treatment of political radicalism in the 1907 novel The Secret Agent.

In her influential study The Gothic Body, Kelly Hurley draws attention to the literary device of the abhuman as a representation of damaged personal identity, and to lesser-known authors in the field, including Richard Marsh (1857–1915), author of The Beetle (1897), and William Hope Hodgson (1877–1918), author of The Boats of the Glen Carrig, The House on the Borderland and The Night Land.[20] In 1897, Bram Stoker published Dracula, an enormously influential Gothic novel featuring the parasitic vampire Count Dracula in an extended exercise of reversed imperialism. Unusually, Stoker makes explicit reference to the writings of Lombroso and Nordau in the course of the novel.[21] Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories include a host of degenerationist tropes, perhaps best illustrated (drawing on the ideas of Serge Voronoff) in The Adventure of the Creeping Man.

Literary conventions

In the Victorian fin de siècle, the themes of degeneration and anxiety are expressed not only through the physical landscape which provided a backdrop for Gothic Literature, but also through the human body itself. Works such as Robert Louis Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), Arthur Machen's The Great God Pan (1894), H. G. Wells' The Time Machine (1895), and Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897) all explore themes of change, development, evolution, mutation, corruption and decay in relation to the human body and mind. These literary conventions were a direct reflection of many evolutionary, scientific, social and medical theories and advancements that emerged toward the end of the 19th century.[22]

Artistic conventions

The works of the Decadents and the Aesthetes contain the hallmarks typical of fin de siècle art. Holbrook Jackson's The Eighteen Nineties describes the characteristics of English decadence, which are: perversity, artificiality, egoism, and curiosity.[14] The first trait is the concern for the perverse, unclean, and unnatural.[13] Romanticism had encouraged audiences to view physical traits as indicative of one's inner self. Fin de siècle artists accepted beauty as the basis of life, and so valued that which was not conventionally beautiful.[14]

This belief in beauty in the abject leads to the obsession with artifice and symbolism, as artists rejected ineffable ideas of beauty in favor of the abstract.[14] Through symbolism, aesthetes could evoke sentiments and ideas in their audience without relying on an infallible general understanding of the world.[16]

The third trait of the culture is egoism, a term similar to that of "egomania," meaning disproportionate attention placed on one's own endeavors. This can result in a type of alienation and anguish, as in Baudelaire's case, and demonstrates how aesthetic artists chose cityscapes over country as a result of their aversion to the natural.[13]

Finally, curiosity is identifiable through diabolism and the exploration of the evil or immoral, focusing on the morbid and macabre, but without imposing any moral lessons on the audience.[14][19]

See also

- Belle Époque

- Decadent movement

- Futurism

- Gay Nineties

- Lost generation

- Reactionary politics

- Symbolism (arts)

Footnotes

- ↑ Talia Schaffer, Literature and Culture at the Fin de Siècle (New York, N.Y.: Pearson Longman, 2007, ISBN 978-0321132178), 3.

- ↑ Stjepan Meštrović, The Coming Fin de Siecle: An Application of Durkheim's Sociology to modernity and postmodernism (1991; Oxford, U.K. and New York, N.Y.: Routledge, 1992, ISBN 978-0415853613), 2.

- ↑ Nicoletta Pireddu, "Primitive marks of modernity: cultural reconfigurations in the Franco-Italian fin de siècle," Romanic Review 97 (3–4) (2006): 371–400. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ↑ Patrick McGuinness, ed., Symbolism, Decadence and the Fin de Siècle: French and European Perspectives (Exeter, U.K.: Exeter University Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0859896467), 9.

- ↑ Nicoletta Pireddu, Antropologi alla corte della bellezza. Decadenza ed economia simbolica nell'Europa fin de siècle (Verona, IT: Fiorini, 2002, ISBN 8887082162).

- ↑ J. Trygve Has-Ellison, "Nobles, Modernism, and the Culture of fin-de-siècle Munich," German History 26(1) (2008): 1–23.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Zeev Sternhell, "Crisis of Fin-de-siècle Thought," in International Fascism: Theories, Causes and the New Consensus (London, U.K. and New York, N.Y.: Bloomsbury Academic, 1998, ISBN 978-0340706138), 169.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Stanley G. Payne, A history of fascism, 1914–1945 (1995; Oxford, U.K.: Routledge, 2005, ISBN 978-1857285956), 23–24.

- ↑ Stephen Kern, Culture of Time and Space, 1880–1918 (Boston, MA & London, U.K.: Harvard University Press, 1983, ISBN 978-0674179738).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Michael Heffernan, "Fin de Siècle, Fin du Monde? On the Origins of European Geopolitics; 1890–1920," in Geopolitical Traditions: A Century of Geopolitical Thought eds., Klaus Dodds & David A. Atkinson (London, U.K. & New York, N.Y.: Routledge, 2000, ISBN 978-0415172493), 28, 31. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ↑ Michael Heffernan, "The Politics of the Map in the Early Twentieth Century," Cartography and Geographic Information Science 29(3) (2002): 207.

- ↑ Thomas Owens Mackubin, "In Defense of Classical Geopolitics," Naval War College Review 52(4) (1999): 65. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Glyn Hambrook, "Baudelaire, Degeneration Theory, and Literary Criticism," The Modern Language Review 101(4) (2006): 1005–1024.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Russel Goldfarb, "Late Victorian Decadence," The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 20(4) (1962): 369–373.

- ↑ Catherine Maxwell, "Theodore Watts-Dunton's 'Aylwin (1898)' and the Reduplications of Romanticism," The Yearbook of English Studies 37(1) (2007): 1–21.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "What Is Fin de Siecle?" The Art Critic 1(1) (1893): 9.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Nicholas Shrimpton, "'Lane, You're a Perfect Pessimist': Pessimism and the English 'Fin de siècle'," The Yearbook of English Studies 37(1) (2007): 41–57.

- ↑ Marion Thain, "Modernist 'Homage' to the 'Fin de siècle'," The Yearbook of English Studies 37.1 (2007): 22–40.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 John Allen Quintus, "The Moral Implications of Oscar Wilde's Aestheticism," Texas Studies in Literature and Language 22(4) (1980): 559–574.

- ↑ Kelly Hurley, The Gothic Body: Sexuality, Materialism, and Degeneration at the Fin de Siècle (Cambride, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0511519161).

- ↑ Fiona Subotsky, Dracula for doctors: medical facts and Gothic fantasies (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2019, ISBN 978-1911623281).

- ↑ Greg Buzwell, "Gothic fiction in the Victorian fin de siècle: mutating bodies and disturbed minds," The British Library, May 15, 2014. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ↑ West Shearer, Fin de Siecle: Art and Society in an Age of Uncertainty (New York, N.Y.: Overlook Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0879515195).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Goldfarb, Russel, "Late Victorian Decadence," The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 20(4) (1962): 369–373.

- Hambrook, Glyn, "Baudelaire, Degeneration Theory, and Literary Criticism," The Modern Language Review 101(4) (2006): 1005–1024.

- Has-Ellison, J. Trygve, "Nobles, Modernism, and the Culture of fin-de-siècle Munich," German History 26(1) (2008): 1–23.

- Heffernan, Michael, "Fin de Siècle, Fin du Monde? On the Origins of European Geopolitics; 1890–1920," in Geopolitical Traditions: A Century of Geopolitical Thought eds., Klaus Dodds & David A. Atkinson. London, U.K. & New York, N.Y.: Routledge, 2000, ISBN 978-0415172493). Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- Heffernan, Michael, "The Politics of the Map in the Early Twentieth Century," Cartography and Geographic Information Science 29(3) (2002): 207.

- Kern, Stephen, Culture of Time and Space, 1880–1918. Boston, MA & London, U.K.: Harvard University Press, 1983, ISBN 978-0674179738.

- Mackubin, Thomas Owens, "In Defense of Classical Geopolitics," Naval War College Review 52(4) (1999): 65. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- Maxwell, Catherine, "Theodore Watts-Dunton's 'Aylwin (1898)' and the Reduplications of Romanticism," The Yearbook of English Studies 37(1) (2007): 1–21.

- McGuinness, Patrick, ed., Symbolism, Decadence and the Fin de Siècle: French and European Perspectives. Exeter, U.K.: Exeter University Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0859896467.

- Meštrović, Stjepan, The Coming Fin de Siecle: An Application of Durkheim's Sociology to modernity and postmodernism. 1991; Oxford, U.K. and New York, N.Y.: Routledge, 1992, ISBN 978-0415853613.

- Payne, Stanley G., A history of fascism, 1914–1945. Oxford, U.K.: Routledge, 2005 (original 1995), ISBN 978-1857285956.

- Pireddu, Nicoletta, Antropologi alla corte della bellezza. Decadenza ed economia simbolica nell'Europa fin de siècle. Verona, IT: Fiorini, 2002, ISBN 8887082162.

- Pireddu, Nicoletta, "Primitive marks of modernity: cultural reconfigurations in the Franco-Italian fin de siècle," Romanic Review 97 (3–4) (2006): 371–400. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- Quintus, John Allen, "The Moral Implications of Oscar Wilde's Aestheticism," Texas Studies in Literature and Language 22(4) (1980): 559–574.

- Schaffer, Talia, Literature and Culture at the Fin de Siècle. New York, N.Y.: Pearson Longman, 2007, ISBN 978-0321132178.

- Shrimpton, Nicholas, "'Lane, You're a Perfect Pessimist': Pessimism and the English 'Fin de siècle'," The Yearbook of English Studies 37(1) (2007): 41–57.

- Sternhell, Zeev, "Crisis of Fin-de-siècle Thought," in International Fascism: Theories, Causes and the New Consensus. London, U.K. and New York, N.Y.: Bloomsbury Academic, 1998, ISBN 978-0340706138.

- Thain, Marion, "Modernist 'Homage' to the 'Fin de siècle'," The Yearbook of English Studies 37.1 (2007): 22–40.

- "What Is Fin de Siecle?" The Art Critic 1(1) (1893): 9.

Further reading

- Schwartz, Hillel. Century's End: A Cultural History of the Fin de Siècle—From the 990s Through the 1990s. New York: Doubleday, 1990.

- (1982) La Belle Époque. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0870993299.

External links

- Fin de Siècle at The British Library

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.