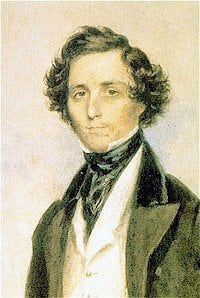

Felix Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, born and known generally as Felix Mendelssohn (February 3, 1809 – November 4, 1847) was a German composer and conductor of the early Romantic period. He was born to a notable Jewish family – his grandfather Moses Mendelssohn was a distinguished philosopher and the parents held salon frequented by the German elite. His work, characterized as ??? amidst complexity espoused by Berlioz and others, includes symphonies, concertos, oratorios, piano and chamber music. He revived interest in Bach, who had been forgotten and denigrated as ???. For this he was more popular in England than in continental Europe. After a long period of relative denigration due to changing musical tastes in the late 19th century, his creative originality is being recognised and re-evaluated, and he is amongst the most popular composers of the Romantic era.

Life

Family Background

Mendelssohn was born in Hamburg. Father Abraham was the son of philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, a contemporary of Immanuel Kant, whose treatise on the immortality of the soul, Phaedon, was translated into more than 30 languages. Some of Moses' family left the Jewish faith in an effort to be accepted in European society, but he chose to modernize traditional Jewish learning by reconciling it with the new, secular, environment. Leah Salomon was from the Itzig family of prominent and rich Berlin Jews. Felix's background was cosmopolitan, and he himself traveled extensively.

At the time of his birth, Abraham and his brother were running a bank, but the devastating Napoleonic blockade sent the family fleeding to Berlin in 1812, then a provincial town. The position of Jews had been improved by recent legislation but there was mounting pressure to assimilate. Leah's brother converted to Christianity and took the name Bartholdy, and he suggested that Felix do the same. Abraham even encouraged Felix to drop the name of Mendelssohn. The children were first brought up without religious education and were baptised as Lutherans in 1816 (at which time Felix took the additional names Jakob Ludwig). Abraham and his wife were baptised later. Felix signed his letters as 'Mendelssohn Bartholdy' in obedience to his father's injunctions.[1]

The Mendelssohns enjoyed prestige in the city, and Jews and Gentiles alike sought to attend their afternoon salon. The family had famous virtuosos, including Franz Liszt, perform at their house. The period did not favor free speech, so music, rather than conversation, was the source of entertainment. They also staged amateur dramatics, performing plays such as Shakespeare's ''A Midsummer Night's Dream''. Among the family friends were the Humboldt brothers, Heine, and Hegel.

The Mendelssohns were hard-working, allowing their four children Felix, his brother Paul, and sisters Fanny and Rebecka, to get up after 5 am only on Sundays. Felix and three years older Fanny were musical child prodigies. Mendelssohn is often regarded as the greatest precocious child after Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Abraham and Leah sought to give their children best education possible. Fanny became a well-known pianist and amateur composer; originally Abraham had thought that she might be the more musical one. However, at that time, it was not considered proper for a woman to have a career in music, and her father and brother prohibited her from publishing her compositions.

Felix and Fanny doted on each other. Felix was a beautiful boy, whose face the English novelist Thackeray likened to Saviour's. He was athletic and rode, danced and swam well. However, this fueled his air of self-assurance and moodiness, and he was perceived as intolerant, dogmatic, and irritable.

Early Entrance into Music

Felix probably made his first public concert appearance at the age of nine, when he participated in a chamber music concert. As an adolescent, he saw his works performed at home with a private orchestra for the visitors of his parents' salon. He was also a prolific composer as a child and wrote his first published work, a piano quartet, by the time he was thirteen. Twelve string symphonies were produced between the ages of 12 and 14. These works were ignored for over a century but are now recorded and heard occasionally in concerts. In 1824, still aged only 15, he wrote his first symphony for full orchestra (in C minor, Op. 11). At the age of 16, he wrote the String Octet in E Flat Major, the first work which showed the full power of his genius. The Octet and his overture to Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, written a year later, are the best known of his early works. He wrote incidental music for the play 16 years later in 1842, including the famous Wedding March.

On his fifteenth birthday, after the first rehearsal of his opera Der Onkel aus Boston (The Two Nephews), his composition teacher Zelter told him he was no longer "an apprentice but a fully-fledged member of the brotherhood of musicians" such as Mozart, Haydn, and Bach. However, his parents did not believe that the ability alone would guarantee Felix a career in music and took him to Paris, where he expressed concern that the Parisians did not know Beethoven's Fidelio and held Bach in low regard.

Year 1827 saw the premiere — and due to unfavorable reception the sole performance in his lifetime — of his opera Die Hochzeit des Camacho. He would not attempt at this genre again.

Education

Mendelssohn began taking piano lessons from his mother when he was six. From 1817 he studied composition with director of the Berlin Singakademie Carl Friedrich Zelter. Zelter introduced him to the elderly Goethe, and when the 12-year old was taken to stay with Goethe in Weimar, he played music for him for rarely less than four hours. He later took lessons from the composer and piano virtuoso Ignaz Moscheles who, however, confessed in his diaries [2] that he had little to teach him. Moscheles became a close colleague and lifelong friend.

Besides music, Mendelssohn's education included art, literature, languages, and philosophy. He was a skilled artist in pencil and watercolour and spoke English, Italian, and Latin. He showed an interest in classical literature. His enormous correspondence shows that he could also be a witty writer (in both German and English - and sometimes accompanied by humorous sketches and cartoons in the text).

From 1826 to 1829, Mendelssohn studied at the University of Berlin where he attended lectures on aesthetics, history, and geography.

Travels to Britain

In 1829, Mendelssohn paid his first visit to Britain, where Moscheles, already settled in London, introduced him to the local influential musical circles. With great success he conducted his First Symphony and played in public and private concerts. He visited Edinburgh and became a friend of composer John Thomson. On subsequent visits he met with Queen Victoria and her musical husband Prince Albert, both of whom were great admirers of his music. In the course of ten visits to Britain during his life, he won a strong following, and the country inspired two of his most famous works, the overture Fingal's Cave (also known as the Hebrides Overture) and the Symphony No. 3 (Scottish Symphony). His oratorio Elijah was premiered in Birmingham in 1846.

Career

Mendelssohn declined the offer to become professor of music at the University of Berlin in 1830. Instead he traveled for two years around Europe. Then he moved to the Paris of Balzac, Hugo, Chopin, and Liszt, with Grand Opera at its height. The atmosphere of dandyism and philandering repulsed him, and when the premiere of his Reformation Symphony was canceled because the Paris orchestra saw too much counterpoint in it and too few tunes, he escaped the city never to return.

On the death of Zelter, Mendelssohn's father ordered him back to Berlin to aply for Zelter's job at the Berlin Singakademie but the reluctant composer was turned down. This was speculated to be because of his youth, fear of possible innovations, or his Jewish origins.

In 1833 he took over as director of music at Düsseldorf, where he directed rehearsals and concerts and watched over music mainly in Roman Catholic churches. He set out to raise the standards of performance but with the orchestra occasionally intoxicated and the orchestral playing generally viewed as stifling the development of modern music (Liszt treated performances as rehearsals and Italian conductors tapped on candleholders), it became obvious that a conductor was essential. St. Paul composed during this tenure was performed in 41 German cities within 18 months of its publication and soon reached other European countries and America.

Mendelssohn lost his job after a fight with the management but was soon accepted by Leipzig Gewandhaus. There a better orchestra was at his disposal, and he even took a personal interest in the musicians who worked for him, helping those in need. He worked as conductor there from 1835 until his death, turning it into one of the greatest in Germany.

This appointment was extremely important for him; he considered himself a German and wished to play a leading part in his country's musical life.

In 1843 he founded the Leipzig Conservatory, where he successfully persuaded Moscheles and Robert Schumann to join him. After a personal interview with the King of Prussia, Frederick William IV, he accepted the post of director of the musical side of the new Berlin Academy of Arts, but his focus remained on developing the musical life of Leipzig.

Family Life

Mendelssohn's personal life was traditional, without excesses. After he met his future wife Cécile Jeanrenaud in March 1837, he decided to test the depth of his feelings in solitude of a gloomy North Sea town. Having found them unchanged, he proposed to Cecile. His family was not present at the wedding held the same year. Sister Fanny was jealous and the mother disturbed. The snobbish mother-in-law thought her daughter could have done better. The couple weathered this and gave birth to five children: Carl, Marie, Paul, Felix, and Lilli.

Final Years of Life

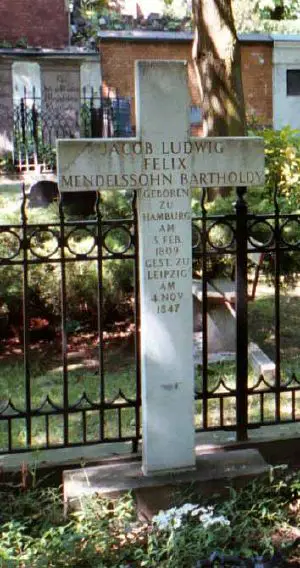

Mendelssohn suffered from bad health in the final years of his life, probably aggravated by nervous problems and overwork. He described himself as leading a 'vegetable existence'. When he finally returned to Leipzig, he could only compose, not condocut. Then came Fanny's death in May 1847, which distressed him to the point that his wife Cecile organized a holiday in Switzerland to help him recover. However, when Felix came back and went to Fanny's room, the pain resurfaced to an extent that he had to cancel a performance of Elijah. He felt very tired and died in Leipzig in November of the same year of a brain haemorrhage at 38, after a series of strokes.

His funeral was held at the Paulinerkirche (St Paul's Church). Thousands filed past the open coffin. Music lovers in Germany and several other countries, particularly Britain, where he had been so popular, mourned his death. After the service, the train left for Berlin, and during a stop at Dessau, a chorus sang on the platform. In Berlin a great crowd attended and Felix was laid to rest in the family vault in the Dreifaltigkeitsfriedhof (Trinity Cemetery) I in Berlin-Kreuzberg.

beside his beloved sister.

Revival of Bach's and Schubert's music

M was always interested in Bach, whose works were hard to come by. The St. Matthew Passion Mendelssohn's own works show his study of Baroque and early classical music. His fugues and chorales especially reflect a tonal clarity and use of counterpoint reminiscent of Johann Sebastian Bach, by whom he was deeply influenced. His great-aunt, Sarah Levy (née Itzig) was a pupil of Bach's son, Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, and had supported the widow of another son Carl Philipp Emmanuel Bach. She had collected a number of Bach manuscripts. J.S. Bach's music, which had fallen into relative obscurity by the turn of the 19th century, was also deeply respected by Mendelssohn's teacher Zelter. In 1829, with the backing of Zelter and the assistance of a friend, the actor Eduard Devrient, Mendelssohn arranged and conducted a performance in Berlin of Bach's St Matthew Passion. The orchestra and a choir of 400 were provided by the Berlin Singakademie of which Zelter was the principal conductor. M cut the score, omitted much of what did not relate directly to the Passion, filled out hte instrumentation and provided sound effects. By so doing, he started the process of alteration and truncation that was applied throughout the Bach revival.

The success of this performance (the first since Bach's death in 1750) was an important element in the revival of J.S. Bach's music in Germany and, eventually, throughout Europe. It earned Mendelssohn widespread acclaim at the age of twenty. It also led to one of the very few references which Mendelssohn ever made to his origins: 'To think that it took an actor and a Jew-boy to revive the greatest Christian music for the world' (cited by Devrient in his memoirs of the composer).

After the performance of the Passion, Abraham sent him to travel abroad to broaden his outlook and sent him to Britain. In London, he was sou ght after by the most fashionable hostesses: handsome, elegant and witty, and rich. However, had he been seen as a professional musician, he would have had to enter the great houses by the servants' entrance, like Moscheles did.

Mendelssohn also revived interest in the work of Franz Schubert. He conducted the premiere of Schubert's Ninth Symphony at Leipzig on 21 March, 1839, more than a decade after the composer's death.

Contemporaries

Considered Berlioz' instrumentation filthy. compared to Berlioz, M was almost excessively refined and restrained,a lmost classical in his clarity and structures. In his life and music - little excessive enthusiasm or exaggeration displayed by Berlioz. Associated with religiosity, sentimentality - Victorian values. THe VIctorians loved his oratiorios, melodious sacred music.

Throughout his life Mendelssohn was wary of the more radical musical developments undertaken by some of his contemporaries. He was generally on friendly, if somewhat cool, terms with the likes of Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt, and Giacomo Meyerbeer, but in his letters expresses his frank disapproval of their works.

In particular, he seems to have regarded Paris and its music with the greatest of suspicion and an almost Puritanical distaste. Attempts made during his visit there to interest him in Saint-Simonianism ended in embarrassing scenes. He thought the Paris style of opera vulgar, and the works of Meyerbeer insincere. When Ferdinand Hiller suggested in conversation to Felix that he looked rather like Meyerbeer (they were distant cousins, both descendants of Rabbi Moses Isserlis), Mendelssohn was so upset that he immediately went to get a haircut to differentiate himself. It is significant that the only musician with whom he was a close personal friend, Moscheles, was of an older generation and equally conservative in outlook. Moscheles preserved this outlook at the Leipzig Conservatory until his own death in 1870.

Reputation

This conservative strain in Mendelssohn, which set him apart from some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, bred a similar condescension on their part toward his music. His success, his popularity and his Jewish origins, irked Richard Wagner sufficiently to damn Mendelssohn with faint praise, three years after his death, in an anti-Jewish pamphlet Das Judenthum in der Musik. This was the start of a movement to denigrate Mendelssohn's achievements which lasted almost a century, the remnants of which can still be discerned today amongst some writers (for example, Charles Rosen's essay on Mendelssohn, whose style he criticizes as 'religious kitsch'). [3] The Nazi regime was to cite Mendelssohn's Jewish origin in banning his works and destroying memorial statues.

In England, Mendelssohn's reputation remained high for a long time; the adulatory (and today scarcely readable) novel Charles Auchester by the teenaged Sarah Sheppard, published in 1851, which features Mendelssohn as the 'Chevalier Seraphael', remained in print for nearly eighty years. Queen Victoria demonstrated her enthusiasm by requesting, when The Crystal Palace was being re-built in 1854, that it include a statue of Mendelssohn. It was the only statue in the Palace made of bronze and the only one to survive the fire that destroyed the Palace in 1936. (The statue is now situated in Eltham College, London). Mendelssohn's Wedding March from A Midsummer Night's Dream was first played at the wedding of Queen Victoria's daughter to the crown prince of Prussia in 1856 and it is still popular today. However many critics, including Bernard Shaw, began to condemn his music for its association with Victorian cultural insularity.

His reputation suffered but his oratorios and sacred music were adored in Victorian England. Wagner damned M's reputation by describing the Hebrides Overture as 'so clear, so smooth, so melodious, as definite in form as a crystal, but also just as cold'. He called M 'a landscape painter, incapable of depicting a human being'. Schumann saw in him the reconciliation of the classical and teh Romantic but with too much elegance and refinement.

His style was similar to Weber and Schubert. T

Over the last fifty years a new appreciation of Mendelssohn's work has developed, which takes into account not only the popular 'war horses', such as the E minor Violin Concerto and the Italian Symphony, but has been able to remove the Victorian varnish from the oratorio Elijah, and has explored the frequently intense and dramatic world of the chamber works. Virtually all of Mendelssohn's published work is now available on CD.

Recent critical evaluations of Mendelssohn's work have stressed the subtlety of his compositional technique. For example, the Hebrides Overture has been interpreted as presenting a musical equivalent to the aesthetic subject in the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich. The first lyrical theme represents the person apprehending the landscape described by the music behind this theme. Similarly, the use of French Horns in the opening movement of the Italian Symphony may represent a German presence in an Italian scene — Mendelssohn himself on tour.

Works

- Octet in E-Flat Major, for strings – 1825

- Overture to a Midsummer Night's Dream, for orchestra, op. 21 – 1826

- String Quartet No. 1 in E-Flat Major – 1829

- Rondo Capriccioso, for solo piano – 1829

- Capriccio Brilliant in B Minor, for piano and orchestra – 1829

- Lieder Ohne Worte (Songs Without Words), for solo piano 1830 – 1835

- Symphony No.5 in D Major, "Reformation" – 1830

- Concerto No. 1 in G Minor, for piano and orchestra – 1831

- Concert Overtures, for orchestra 1832 – 1833

- Fingal's Cave (or Hebrides)

- Meeresstille und Glueckliche Fahrt (Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage)

- Die Schoene Melusina (Fair Melusina)

- Symphony No. 4 in A Major-Minor, "Italian" – 1833

- Songs, for voice and piano 1834-1837

- "An die Entfernte"

- "Auf Fluegeln des Gesanges"

- "Gruss"

- "Jagdlied"

- "Lieblingsplaetzchen"

- "Nachtlied"

- "O Jugend"

- "Schilflied"

- "Volkslied"

- St. Paul, oratorio for solo voices, chorus, and orchestra – 1835

- 6 Preludes and Fugues, for solo piano 1836-1837

- Piano Trio No. 1 in D Minor – 1839

- Ruy Blas, concert overture for orchestra – 1839

- Variations Serieuses in D Minor, for piano – 1841

- Symphony No. 3 in A Minor-Major, "Scotch" – 1842

- A Midsummer Night's Dream, incidental music for voice, chorus, and orchestra – 1843

- Concerto in E Minor, for violin and orchestra – 1844

- Elijah, oratorio for solo voices, chorus, and orchestra – 1846

Juvenilia and early works

The young Mendelssohn was greatly influenced in his childhood by the music of Bach, Beethoven and Mozart and these can all be seen, albeit often rather crudely, in the twelve early 'symphonies,' mainly written for performance in the Mendelssohn household and not published or publicly performed until long after his death.

His astounding capacities are, however, clearly revealed in a clutch of works of his early maturity: the String Octet (1825), the Overture A Midsummer Night's Dream (1826), and the String Quartet in A minor (listed as no. 2 but written before no. 1) of 1827. These show an intuitive grasp of form, harmony, counterpoint, colour and the compositional technique of Beethoven which justify the claims often made that Mendelssohn's precocity exceeded even that of Mozart in its intellectual grasp.

Symphonies

Mendelssohn wrote 12 symphonies for string orchestra from 1821 to 1823 (i.e. between the ages of 12 and 14).

The numbering of his mature symphonies is approximately in order of publishing, rather than of composition. The order of composition is: 1, 5, 3, 4, 2.

Symphony No. 1 in C minor for full-scale orchestra was written in in 1824, when Mendelssohn was aged 15. This work is experimental, showing the influence of Bach, Beethoven and Schubert.

From 1829 to 1830 he wrote his Symphony No. 5 in D Major, known as the Reformation. Despite its quality, Mendelssohn remained dissatisfied with it and did not allow publication of the score.

The Scottish Symphony (Symphony No. 3 in A minor), was written and revised intermittently between 1830 and 1842. This piece evokes Scotland's atmosphere in the ethos of Romanticism, but does not employ actual Scottish folk melodies. Mendelssohn published the score of the symphony in 1842.

Mendelssohn travelled widely in Europe throughout his life, and a visit to Italy inspired him to write the Symphony No 4 in A major, known as the Italian. Mendelssohn conducted the premiere in 1833, but he did not allow this score to be published during his lifetime as he continually sought to rewrite it.

In 1840 Mendelssohn wrote the choral Symphony No. 2 in B flat Major, entitled Lobgesang (Hymn of Praise), and this score was published in 1841.

Other orchestral music

Mendelssohn wrote the concert overture The Hebrides (Fingal's Cave) in 1830, inspired by visits he made to Scotland around the end of the 1820s. He visited the cave, on the Hebridean isle of Staffa, as part of his Grand Tour of Europe, and was so impressed that he scribbled the opening theme of the overture on the spot, including it in a letter he wrote home the same evening.

Throughout his career he wrote a number of other concert overtures; those most frequently played today include Ruy Blas written for the drama by Victor Hugo and Meerestille und Glückliche Fahrt (Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage) inspired by the poem by Goethe.

The incidental music to A Midsummer Night's Dream (op. 61), including the well-known Wedding March, was written in 1843, seventeen years after the overture.

Opera

Mendelssohn wrote some Singspiels for family performance in his youth. In 1827 he wrote a more sophisticated work, Die Hochzeit von Camacho, based on an episode in Don Quixote, for public consumption. This was however not a success - Mendelssohn left the theatre before the conclusion of the first performance and subsequent performances were cancelled.

Although he never abandoned the idea of composing a full opera, and considered many subjects - including that of the Nibelung saga later adapted by Wagner - he never wrote more than a few pages of sketches for any project. In his last years the manager Benjamin Lumley tried to contract him to write an opera on The Tempest on a libretto by Eugène Scribe, and even announced it as forthcoming in the year of Mendelssohn's death. The libretto was eventually set by Fromental Halévy.

Concertos

Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto in E Minor, op. 64 (1844), written for Ferdinand David, has become one of the most popular of all of Mendelssohn's compositions. Many violinists have commenced their solo careers with a performance of this concerto, including Jascha Heifetz, who gave his first public performance of the piece at the age of seven.

Mendelssohn also wrote two piano concertos, a less well known, early, violin concerto, and a double concerto for piano and violin. In addition, there are several works for soloist and orchestra in one movement. Those for piano are the Rondo Brillant, Op. 29 of 1834; the Capriccio Brillant, Op. 22 of 1832; and the Serenade and Allegro Giojoso Op. 43 of 1838. Opp. 113 and 114 are Konzertstücke (concerto movements) for clarinet, basset horn, and piano that were orchestrated and performed in that form in Mendelssohn's lifetime.

Chamber Music

Mendelssohn's mature output contains many chamber works many of which display an emotional intensity some people think lacking in his larger works. In particular his string quartet op. 80 in F minor (1847), his last major work, written following the death of his sister Fanny, is both powerful and eloquent. Other works include two string quintets, sonatas for the clarinet, cello, viola and violin, and two piano trios. For the first of these trios, in D minor (1839), Mendelssohn unusually took the advice of a fellow-composer, (Ferdinand Hiller) and rewrote the piano part in a more romantic, 'Schumannesque' style, considerably heightening its effect.

Choral

The two large biblical oratorios, 'St Paul' in 1836 and 'Elijah' in 1846, are greatly influenced by Bach. 'Elijah' is especially popular, combining some of Mendelssohn's most dramatic music with his most sublime. One of Mendelssohn's most frequently performed sacred pieces is "There Shall a Star Come out of Jacob", a chorus from the unfinished oratorio, 'Christus' (which together with the preceding recitative and male trio comprises all of the existing material from that work). Mendelssohn also wrote many smaller-scale sacred works for unaccompanied choir and for choir with organ including 'Hear my prayer', which includes the famous solo 'O for the wings of a dove'.

Strikingly different is the more overtly 'romantic' Die Erste Walpurgisnacht (The First Walpurgis Night), a setting for chorus and orchestra of a ballad by Goethe describing pagan rituals of the Druids in the Harz mountains in the early days of Christianity. This remarkable score has been seen by the scholar Heinz-Klaus Metzger as a "Jewish protest against the domination of Christianity".

Songs

Mendelssohn wrote many songs for solo voice and duet. Some of these, such as 'O for the wings of a Dove' (adapted from the anthem Hear My Prayer) became extremely popular. A number of songs written by Mendelssohn's sister Fanny originally appeared under her brother's name; this was partly due to the prejudice of the family, and partly to her own diffidence.

Piano

Mendelssohn's Lieder ohne Worte (Songs Without Words), eight cycles each containing six lyric pieces (2 published posthumously), remain his most famous solo piano compositions. They became standard parlour recital items, and their overwhelming popularity has caused many critics to under-rate their musical value. Other composers who were inspired to produce similar pieces of their own included Charles Valentin Alkan (the five sets of Chants, each ending with a barcarolle), Anton Rubinstein, Ignaz Moscheles and Edvard Grieg.

Other notable piano pieces by Mendelssohn include his Variations sérieuses op. 54 (1841), the Seven Characteristic Pieces op. 7 (1827) and the set of six Preludes and Fugues op. 35 (written between 1832 and 1837).

Organ

Mendelssohn played the organ and composed for it from the age of 11 to his death. His primary organ works are the Three Preludes and Fugues, Op. 37 (1837), and the Six Sonatas, Op. 65 (1845).

Media

Symphony no. 3 in A minor ("Scottish")

|

See also

- Itzig family

- Abraham Mendelssohn

Notes

References and further reading

- Hensel, Sebastian: The Mendelssohn Family. 4th revised edition, London, 1884 (often reprinted).

- Edited by Felix's nephew, an important collection of letters and documents about the family.

- Jacob, Heinrich Eduard: Felix Mendelssohn and his Time, London, 1963* Mercer-Taylor, Peter: The Life of Mendelssohn, Cambridge, 2000. ISBN 0-521-63972-7.

- In the Cambridge University series of musical lives, compact and reliable.

- Moscheles, Charlotte: Life of Moscheles, with selections from his Diaries and Correspondence, London, 1873 (2 volumes).* Steen, Michael: The Lives and Times of the Great Composers Cambridge, 2003. ISBN 1-84046-485-2.

- The Complete Book of Classical Music. Edited by David Ewen. London, 1965. ISBN 0-7090-3865-8.

- Todd, R. Larry: Mendelssohn - A Life in Music Oxford and New York, 2003. ISBN 0-19-511043-9

- The most recent (as of December 2005) comprehensive survey.

- Werner, Eric: Mendelssohn, A New Image of the Composer and his Age, New York and London, 1963.

- A pioneering re-evaluation when first published, now the subject of controversy because of Werner's unnecessarily over-enthusiastic interpretation of some documentation in an attempt to establish Felix's Jewish sympathies. See Musical Quarterly, vols. 82-83, articles by Sposato, Leon Botstein and others.

There are numerous published editions and selections of Felix's letters. A complete edition is now (2006) in preparation but is expected to take twenty years to complete.

The main collections of Mendelssohn's original musical autographs and letters are to be found in the Bodleian Library, Oxford University, the New York Public Library, and the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin. His letters to Moscheles are in the Brotherton Collection, Leeds University.

External links

- Felix Mendelssohn House and Foundation, Leipzig

- Felix Mendelssohn on Carolina Classical site

- Mendelssohn's Scores

- IMSLP - International Music Score Library Project's Mendelssohn page.

- BBC Radio 3 Classical Study and musical links

- Mendelssohn cylinder recordings, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

- ViolinMP3.com - Contains information about the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto

- Free scores by Felix Mendelssohn in the Werner Icking Music Archive

- Template:ChoralWiki

| Preceded by: unknown |

Principal Conductors, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra 1835–1847 |

Succeeded by: Julius Rietz |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.