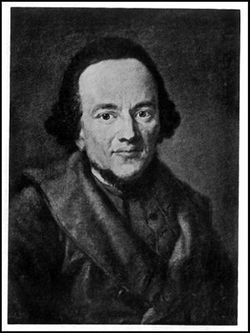

Moses Mendelssohn

Moses Mendelssohn (September 6, 1729 ‚Äď January 4, 1786) was a German Jewish Enlightenment philosopher whose advocacy of religious tolerance resounded with forward-thinking Christians and Jews alike. Mendelssohn‚Äôs most important contribution to philosophy was to refine and strengthen the philosophical proofs for the existence of God, providence and immortality. In 1763, Mendelssohn won the prize offered by the Berlin Academy for an essay on the application of mathematical proofs to metaphysics; Immanuel Kant received an honorable mention.

Mendelssohn strove to support and sustain the Jewish faith while advancing the cause of reason. Towards the end of his life, influenced by Kant and Jacobi, he became less confident that metaphysical precepts could be subjected to rational proof, but he did not lose confidence in their truth. He was an important Jewish figure of the eighteenth century, and his German translation of the Pentateuch anchored the Jewish Enlightenment, Haskalah. In 1783, Mendelssohn published Jerusalem, a forcible plea for freedom of conscience, described by Kant as "an irrefutable book." Its basic message was that the state has no right to interfere with the religion of its citizens, and it suggested that different religious truths might be appropriate for different cultures.

He was the grandfather of composer Felix Mendelssohn.

Life

Youth

Mendelssohn was born on September 6, 1729 in Anhalt-Dessau, Germany. His father's name was Mendel and he later took the surname Mendelssohn ("son of Mendel"). Mendel Dessau was a poor scribe, a writer of scrolls. Moses developed curvature of the spine during his boyhood. He received his early education from his father and the local rabbi, David Fränkel, who besides teaching him the Bible and Talmud, introduced to him the philosophy of Maimonides. When Fränkel received a call to Berlin in 1743, Mendelssohn followed him there.

Mendelssohn struggled against crushing poverty, but his scholarly ambition never diminished. A Polish refugee, Zamosz, taught him mathematics, and a young Jewish physician was his tutor in Latin, but he was mainly self-educated. With his scanty earnings he bought a Latin copy of John Locke's Essay Concerning the Human Understanding, and mastered it with the aid of a Latin dictionary. He then made the acquaintance of Aaron Solomon Gumperz, who taught him basic French and English. In 1750 he was hired as teacher of the children of a wealthy silk merchant, Isaac Bernhard, who recognized his abilities and made the young student his book-keeper and later his partner.

In 1754, Mendelssohn was introduced him to Gotthold Lessing; both men were avid chess players. Berlin, in the days of Frederick the Great, was in a moral and intellectual turmoil, and Lessing, a strong advocate of religious tolerance, had recently produced a drama (Die Juden, 1749), intended to show that a Jew can be possessed of nobility of character. Lessing found in Mendelssohn the realization of his ideal. Almost the same age, Lessing and Mendelssohn became close friends and intellectual collaborators. Mendelssohn had written a treatise in German decrying the national neglect of native philosophers (principally Gottfried Leibniz), and lent the manuscript to Lessing. Without consulting him, Lessing published Mendelssohn's Philosophical Conversations (Philosophische Gespr√§che) anonymously in 1755. The same year an anonymous satire, Pope a Metaphysician (Pope ein Metaphysiker), which turned out to be the joint work of Lessing and Mendelssohn, appeared in GdaŇĄsk.

Prominence in Philosophy and Criticism

From 1755, Mendelssohn‚Äôs prominence steadily increased. He became (1756-1759) the leading spirit of Friedrich Nicolai's important literary undertakings, the Bibliothek and the Literaturbriefe; and ran some risk by criticizing the poems of the king of Prussia, who received this criticism good-naturedly. In 1762 he married Fromet Guggenheim. The following year, Mendelssohn won the prize offered by the Berlin Academy for an essay on the application of mathematical proofs to metaphysics; among the competitors were Thomas Abbt and Immanuel Kant. In October 1763, King Frederick granted Mendelssohn the privilege of ‚ÄúProtected Jew‚ÄĚ (Schutz-Jude), assuring his right to undisturbed residence in Berlin.

As a result of his correspondence with Abbt, Mendelssohn resolved to write On the Immortality of the Soul. Materialistic views were rampant at the time and faith in immortality was at a low ebb. Mendelssohn's work, the Ph√§don oder √ľber die Unsterblichkeit der Seele (Ph√§don, or On the Immortality of the Soul, 1767) was modeled on Plato's dialogue of the same name, and impressed the German world with its beauty and lucidity of style. The Ph√§don was an immediate success, and besides being reprinted frequently in German, was speedily translated into nearly all the European languages, including English. The author was hailed as the "German Plato," or the "German Socrates;" and royalty and aristocratic friends showered attentions on him.

Support for Judaism

Johann Kaspar Lavater, an ardent admirer of Mendelssohn, described him as "a companionable, brilliant soul, with piercing eyes, the body of an Aesop; a man of keen insight, exquisite taste and wide erudition ... frank and open-hearted," was fired with the ambition to convert him to Christianity. In the preface to a German translation of Charles Bonnet's essay on Christian Evidences, Lavater publicly challenged Mendelssohn to refute Bonnet, or, if he could not then to "do what wisdom, the love of truth and honesty must bid him, what a Socrates would have done if he had read the book and found it unanswerable." Bonnet resented Lavater's action, but Mendelssohn, though opposed to religious controversy, was bound to reply. As he put it, "Suppose there were living among my contemporaries a Confucius or a Solon, I could, according to the principles of my faith, love and admire the great man without falling into the ridiculous idea that I must convert a Solon or a Confucius."

As a consequence of Lavater's challenge, Mendelssohn resolved to devote the rest of his life to the emancipation of the Jews. Recognizing that secular studies had been neglected among the Jews in Germany, Mendelssohn translated the Pentateuch and other parts of the Bible into German (1783). This work initiated a movement for Jewish secular engagement called Haskalah; Jews learned the German language and culture and developed a new desire for German nationality, and a new system of Jewish education resulted. Some Jewish conservatives opposed these innovations, but the current of progress was too strong for them. Mendelssohn became the first champion of Jewish emancipation in the eighteenth century. In 1781 he induced Christian Wilhelm von Dohm to publish his work, On the Civil Amelioration of the Condition of the Jews, which played a significant part in the rise of tolerance. Mendelssohn himself published a German translation of the Vindiciae Judaeorum by Menasseh Ben Israel.

In 1783, Mendelssohn published Jerusalem (Eng. trans. 1838 and 1852), a forcible plea for freedom of conscience, described by Kant as "an irrefutable book." Its basic message was that the state has no right to interfere with the religion of its citizens. Kant called this "the proclamation of a great reform, which, however, will be slow in manifestation and in progress, and which will affect not only your people but others as well." Mendelssohn asserted the pragmatic principle of the possible plurality of truths: that just as various nations need different constitutions, for one a monarchy, for another a republic, might be the most appropriate, so individuals may need different religions. The test of religion is its effect on conduct. This was the moral of Lessing's Nathan the Wise (Nathan der Weise), the hero of which was undoubtedly Mendelssohn, and in which the parable of the three rings was the epitome of the pragmatic position. In the play, Nathan argues that religious differences are due to history and circumstances rather than to reason.

Mendelssohn reconciled Judaism with religious tolerance, maintaining that it was less a "divine need, than a revealed life," and asserting that rather than requiring belief in certain dogmatic truths, it required performance of particular actions intended to reinforce man’s understanding of natural religion.

Later Years and Legacy

In his remaining years, he numbered among his friends many of the greatest men of the age. His Morgenstunden oder Vorlesungen √ľber das Dasein Gottes (Morning Hours or Lectures about God's Existence) appeared in 1785. In 1786 he died as the result of a cold, contracted while carrying to his publishers the manuscript of a vindication of his friend Lessing, who had predeceased him by five years.

Mendelssohn had six children, of whom only Joseph retained the Jewish faith. His sons were: Joseph (founder of the Mendelssohn banking house, and a friend and benefactor of Alexander Humboldt), whose son Alexander (d. 1871) was the last Jewish descendant of the philosopher; Abraham (who married Leah Salomon and was the father of Fanny Mendelssohn and Felix Mendelssohn); and Nathan (a mechanical engineer of considerable repute). His daughters were Dorothea, Recha and Henriette, all gifted women.

‚ÄúSpinoza Dispute‚ÄĚ

Mendelssohn’s most important contribution to philosophy was to refine and strengthen the philosophical proofs for the existence of God, providence and immortality. He strove to support and sustain the Jewish faith while advancing the cause of reason. Towards the end of his life, influenced by Kant and Jacobi, he became less confident that metaphysical precepts could be subjected to rational proof, but he did not lose confidence in their truth.

Mendelssohn’s friend Gotthold Lessing was a particularly strong proponent of the German Enlightenment through his popular plays, his debates with orthodox Lutherans, and his literary works. Both men were optimistic that reason and philosophy would continue to progress and develop, and both embraced the idea of rational religion.

After Lessing died in 1785, Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi published a condemnation of Baruch Spinoza, claiming that his doctrine that God and nature are nothing but extended substance amounted to pure materialism and would ultimately lead to atheism. Jacobi contended that Lessing embraced the pantheism of Spinoza and was an example of the German Enlightenment‚Äôs increasing detachment from religion. Mendelssohn disagreed, saying that there was no difference between theism and pantheism and that many of Spinoza‚Äôs views were compatible with ‚Äútrue philosophy and true religion.‚ÄĚ

Mendelssohn corresponded privately about this matter with Jacobi, who did not respond to him for a long period because of some personal difficulties. Finally, Mendelssohn decided to clarify the issue of Lessing‚Äôs ‚ÄúSpinozism‚ÄĚ in Morning Hours. Jacobi, hearing of this plan, became angry and published their private correspondence a month before Morning Hours was printed, as On the Teaching of Spinoza in Letters to Mr. Moses Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn, upset, countered by quickly writing To the Friends of Lessing: an Appendix to Mr. Jacobi's Correspondence on the Teaching of Spinoza, and legend says that he was so anxious to get the manuscript to the printer that he went out in the bitter cold, forgetting his coat, became ill and died four days later.

As a result of the ‚ÄúSpinoza Dispute‚ÄĚ (Pantheismusstreit), Spinoza‚Äôs philosophy, which had been under a taboo as atheism, was reinstated among German intellectuals, who now regarded pantheism as one of several religious philosophies. Spinoza‚Äôs ideas encouraged German Romanticism, which adored nature as the fulfillment of life and oneness. Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel were also influenced by this dispute; ultimately, Hegel said that there was no philosophy without Spinoza.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Altmann, Alexander. Moses Mendelssohn: A Biographical Study. Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 1998. ISBN 0817368604

- Mendelsohhn, Moses and Daniel O. Dahlstrom (ed.). Moses Mendelssohn: Philosophical Writings (Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy). Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0521574773

- Mendelsohhn, Moses. Moses Mendelssohn: The First English Biography and Translation. Thoemmes Continuum, 2002. ISBN 1855069849

- Mendelssohn, Moses, A. Arkush (trans.) and A. Altmann (intro.). Jerusalem, or, on Religious Power and Judaism. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 1983. ISBN 0874512638

External links

All links retrieved June 1, 2025.

- Moses Mendelssohn Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Moses Mendelssohn Jewish Virtual Library

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.