Erythromycin

| |

Erythromycin

| |

| Systematic name | |

| IUPAC name 6-(4-dimethylamino-3-hydroxy- 6-methyl-oxan-2-yl)oxy- 14-ethyl-7,12,13-trihydroxy- 4-(5-hydroxy-4-methoxy-4,6-dimethyl- oxan-2-yl)oxy-3,5,7,9,11,13-hexamethyl- 1-oxacyclotetradecane-2,10-dione | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 114-07-8 |

| ATC code | J01FA01 |

| PubChem | 3255 |

| DrugBank | APRD00953 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C37H67NO13 |

| Mol. weight | 733.93 g/mol |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 100% |

| Protein binding | 90% |

| Metabolism | liver (under 5% excreted unchanged) |

| Half life | 1.5 hours |

| Excretion | bile |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. | ? |

| Legal status | ? |

| Routes | oral, iv, im, topical |

Erythromycin is a macrolide antibiotic that has an antimicrobial spectrum similar to or slightly wider than that of penicillin, and is often used for people that have an allergy to penicillins. For respiratory tract infections, it has better coverage of atypical organisms, including mycoplasma and Legionellosis. It is also used to treat outbreaks of chlamydia, syphilis, acne, and gonorrhea. It is manufactured and distributed by Eli Lilly and Company.

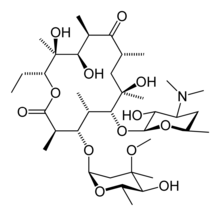

In structure, this macrocyclic compound contains a 14-membered lactone ring with ten asymmetric centers and two sugars (L-cladinose and D-desoamine), making it a compound very difficult to produce via synthetic methods.

Erythromycin is produced from a strain of the actinomycete Saccharopolyspora erythraea, formerly known as Streptomyces erythraeus.

History

Abelardo Aguilar, a Filipino scientist, sent some soil samples to his employer Eli Lilly in 1949. Eli Lilly’s research team, led by J. M. McGuire, managed to isolate Erythromycin from the metabolic products of a strain of Streptomyces erythreus (designation changed to "Saccharopolyspora erythraea") found in the samples.

Lilly filed for patent protection of the compound and U.S. patent 2,653,899 was granted in 1953. The product was launched commercially in 1952 under the brand name Ilosone (after the Philippine region of Iloilo where it was originally collected from). Erythromycin was formerly also called Ilotycin.

In 1981, Nobel laureate (1965 in chemistry) and Professor of Chemistry at Harvard University (Cambridge, MA) Robert B. Woodward, along with a large number of members from his research group, posthumously reported the first stereocontrolled asymmetric chemical synthesis of Erythromycin A.

The antiobiotic clarithromycin was invented by scientists at the Japanese drug company Taisho Pharmaceutical in the 1970s as a result of their efforts to overcome the acid instability of erythromycin.

Available Forms

Erythromycin is available in enteric-coated tablets, slow-release capsules, oral suspensions, ophthalmic solutions, ointments, gels, and injections.

Brand names include Robimycin, E-Mycin, E.E.S. Granules, E.E.S.-200, E.E.S.-400, E.E.S.-400 Filmtab, Erymax, Ery-Tab, Eryc, Erypar, EryPed, Eryped 200, Eryped 400, Erythrocin Stearate Filmtab, Erythrocot, E-Base, Erythroped, Ilosone, MY-E, Pediamycin, Zineryt, Abboticin, Abboticin-ES, Erycin, PCE Dispertab, Stiemycine and Acnasol.

Mechanism of action

Erythromycin may possess bacteriocidal activity, particularly at higher concentrations[1]. The mechanism is not fully elucidated however. By binding to the 50S subunit of the bacterial 70S rRNA complex, protein synthesis and subsequently structure/function processes critical for life or replication are inhibited[2]. Erythromycin interferes with aminoacyl translocation, preventing the transfer of the tRNA bound at the A site of the rRNA complex to the P site of the rRNA complex. Without this translocation, the A site remains occupied and thus the addition of an incoming tRNA and its attached amino acid to the nascent polypeptide chain is inhibited. This interferes with the production of functionally useful proteins and is therefore the basis of antimicrobial action.

Pharmacokinetics

Erythromycin is easily inactivated by gastric acid; therefore, all orally-administered formulations are given as either enteric-coated or more-stable laxatives or esters, such as erythromycin ethylsuccinate. Erythromycin is very rapidly absorbed, and diffuses into most tissues and phagocytes. Due to the high concentration in phagocytes, erythromycin is actively transported to the site of infection, where, during active phagocytosis, large concentrations of erythromycin are released.

Metabolism

Most of erythromycin is metabolised by demethylation in the liver. Its main elimination route is in the bile, and a small portion in the urine. Erythromycin's elimination half-life is 1.5 hours.

Adverse effects

Erythromycin inhibits the cytochrome P450 system, particularly CYP3A4, which can cause it to affect the metabolism of many different drugs. If CYP3A4 substrates, such as simvastatin (Zocor), lovastatin (Mevacor), or atorvastatin (Lipitor), are taken concomitantly with erythromycin, levels of the substrates will increase, often causing adverse effects. A noted drug interaction involves erythromycin and simvastatin, resulting in increased simvastatin levels and the potential for rhabdomyolysis. Another group of CYP3A4 substrates are drugs used for migraine such as ergotamine and dihydroergotamine; their adverse effects may be more pronounced if erythromycin is associated.[3]

Gastrointestinal disturbances, such as diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, and vomiting, are fairly common, so erythromycin tends not to be prescribed as a first-line drug. However, erythromycin may be useful in treating gastroparesis due to this pro-motility effect. Intravenous erythromycin may also be used in endoscopy as an adjunct to clear gastric contents.

More serious side-effects, such as arrhythmia and reversible deafness, are rare. Allergic reactions, while uncommon, may occur, ranging from urticaria to anaphylaxis. Cholestasis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis are some other rare side-effects that may occur.

Exposure to erythromycin (especially long courses at antimicrobial doses, and also through breastfeeding) has been linked to an increased probability of pyloric stenosis in young infants.[4] Erythromycin used for feeding intolerance in young infants has not been associated with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis.[4]

It can also affect the central nervous system, causing psychotic reactions and nightmares and night sweats.[3]

Contraindications

Earlier case reports on sudden death prompted a study on a large cohort that confirmed a link between erythromycin, ventricular tachycardia, and sudden cardiac death in patients also taking drugs that prolong the metabolism of erythromycin (like verapamil or diltiazem) by interfering with CYP3A4 (Ray et al 2004). Hence, erythromycin should not be administered in patients using these drugs, or drugs that also prolong the QT time. Other examples include terfenadine (Seldane, Seldane-D), astemizole (Hismanal), cisapride (Propulsid, withdrawn in many countries for prolonging the QT time) and pimozide (Orap). Theophylline (which is mostly used in asthma) is also contradicted.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Katzung PHARMACOLOGY, 9e Section VIII. Chemotherapeutic Drugs Chapter 44. Chloramphenicol, Tetracyclines, Macrolides, Clindamycin, & Streptogramins

- ↑ Katzung PHARMACOLOGY, 9e Section VIII. Chemotherapeutic Drugs Chapter 44. Chloramphenicol, Tetracyclines, Macrolides, Clindamycin, & Streptogramins

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Erythromycin. Belgian Center for Pharmacotherapeutical Information. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Maheshwai N (March 2007). Are young infants treated with erythromycin at risk for developing hypertrophic pyloric stenosis?. Arch. Dis. Child. 92 (3): 271–3.

- Ray WA, Murray KT, Meredith S, Narasimhulu SS, Hall K, Stein CM. Oral Erythromycin and the Risk of Sudden Death from Cardiac Causes. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1089-96.

- British National Formulary "BNF 49" March 2005.

- Mims C, Dockrell HM, Goering RV, Roitt I, Wakelin D, Zuckerman M. Chapter 33: Attacking the Enemy: Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy: Macrolides. In: Medical Microbiology (3rd Edition). London: Mosby Ltd; 2004. p 489

External links

Template:Acne Agents Template:GlycopeptideAntiBio

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.