Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes (Greek Ἐρατοσθένης; 276 B.C.E. - 194 B.C.E.) was a Greek mathematician, geographer and astronomer. His contemporaries nicknamed him "beta" (Greek for "number two") because he supposedly proved himself to be the second in the ancient mediterranean region in many fields. He is noted for devising a system of latitude and longitude, and for being the first known to have calculated the circumference of the Earth.

Life

Eratosthenes was born in Cyrene (in modern-day Libya), but worked and died in Alexandria, capital of Ptolemaic Egypt. He never married. He was reputedly known for his haughty character. Eratosthenes studied at Alexandria and for some years in Athens. In 236 B.C.E. he was appointed by Ptolemy III Euergetes I as librarian of the Alexandrian library, succeeding the first librarian, Zenodotos, in that post. He made several important contributions to mathematics and science, and was a good friend to Archimedes. Around 255 B.C.E. he invented the armillary sphere, which was widely used until the invention of the orrery in the 18th century. In 194 B.C.E. he became blind and a year later he supposedly starved himself to death.

He is credited by Cleomedes in On the Circular Motions of the Celestial Bodies with having calculated the Earth's circumference around 240 B.C.E., using trigonometry and knowledge of the angle of elevation of the Sun at noon in Alexandria and Syene (now Aswan, Egypt).

Measurement of the Earth

Eratosthenes knew that on the summer solstice at local noon in the town of Syene on the Tropic of Cancer, the sun would appear at the zenith, directly overhead. He also knew, from measurement, that in his hometown of Alexandria, the angle of elevation of the Sun would be 7.2° south of the zenith at the same time. Assuming that Alexandria was due north of Syene he concluded that the distance from Alexandria to Syene must be 7.2/360 of the total circumference of the Earth. The distance between the cities was known from caravan travellings to be about 5000 stadia: approximately 800 km. He established a final value of 700 stadia per degree, which implies a circumference of 252,000 stadia. The exact size of the stadion he used is no longer known (the common Attic stadion was about 185 m), but it is generally believed that the circumference calculated by Eratosthenes corresponds to 39,690 km [citation needed]. The estimate is over 99% of the actual distance of 40,008 km.

Although Eratosthenes' method was well founded, the accuracy of his calculation was inherently limited. The accuracy of Eratosthenes' measurement would have been reduced by the fact that Syene is not precisely on the Tropic of Cancer, is not directly south of Alexandria, and the Sun appears as a disk located at a finite distance from the Earth instead of as a point source of light at an infinite distance. There are other sources of experimental error: the greatest limitation to Eratosthenes' method was that, in antiquity, angles could only be measured to within about a quarter of a degree, and overland distance measurements were even less reliable. So the accuracy of the result of Eratosthenes' calculation is surprising.

Eratosthenes' experiment was highly regarded at the time, and his estimate of the Earth’s size was accepted for hundreds of years afterwards. His method was used by Posidonius about 150 years later.

Other work

Eratosthenes' other contributions include:

- The Sieve of Eratosthenes as a way of finding prime numbers.

- Possibly, the measurement of the Sun-Earth distance, now called the astronomical unit and of the distance to the Moon (see below).

- The measurement of the inclination of the ecliptic with an angle error 7'.

- He compiled a star catalogue containing 675 stars, which was not preserved.

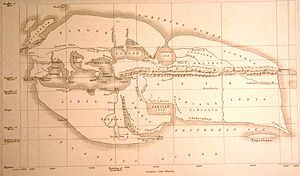

- A map of the Nile's route as far as Khartoum.

- A map of the entire known world, from the British Isles to Ceylon, and from the Caspian Sea to Ethiopia. Only Hipparchus, Strabo, and Ptolemy were able to make more accurate maps in the classical and post-classical world.

- A number of works on theatre and ethics

- A calendar with leap years, in which he attempted to work out the precise dates and relations of various events in politics and literature from his day back to the Trojan War.

The mysterious astronomical distances

Eusebius of Caesarea in his Praeparatio Evangelica includes a brief chapter of three sentences on celestial distances (Book XV, Chapter 53). He states simply that Eratosthenes found the distance to the sun to be "σταδίων μυριάδας τετρακοσίας και οκτωκισμυρίας" (literally "of stadia myriads 400 and 80000") and the distance to the moon to be 780,000 stadia. The expression for the distance to the sun has been translated either as 4,080,000 stadia (1903 translation by E. H. Gifford), or as 804,000,000 stadia (edition of Edouard des Places, dated 1974-1991). The meaning depends on whether Eusebius meant 400 myriad plus 80000 or "400 and 80000" myriad.

This testimony of Eusebius is dismissed by the scholarly Dictionary of Scientific Biography. It is true that the distance Eusebius quotes for the moon is much too low (about 144,000 km) and Eratosthenes should have been able to do much better than this since he knew the size of the earth and Aristarchos of Samos had already found the ratio of the moon's distance to the size of the earth. But if what Eusebius wrote was pure fiction, then it is difficult to explain the fact that, using the Greek stadium of 185 metres, the figure of 804 million stadia that he quotes for the distance to the sun comes to 149 million kilometres. The difference between this and the modern accepted value is less than 1%.

Works

- On the Measurement of the Earth (lost, summarized by Cleomedes)

- Geographica (lost, criticized by Strabo)

- Arsinoe (a memoir of queen Arsinoe; lost; quoted by Athenaeus in the Deipnosophistae)

- A fragmentary collection of Hellenistic myths about the constellations, called Catasterismi (Katasterismoi), was attributed to Eratosthenes, perhaps to add to its credibility.

Named after Eratosthenes

- Sieve of Eratosthenes

- Eratosthenes crater on the Moon

- Eratosthenian period in the lunar geologic timescale

- Eratosthenes Seamount in the eastern Mediterranean Sea

See also

- History of geodesy

Further reading

- Lasky, Kathryn. The Librarian Who Measured the Earth. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1994. ISBN 0-316-51526-4. An illustrated biography for children focusing on the measurement of the earth. Kevin Hawkes, illustrator.

- J J O'Connor and E F Robertson. (January 1999). "Eratosthenes of Cyrene". MacTutor. School of Mathematics and Statistics University of St Andrews Scotland.

- E P Wolfer (1954). Eratosthenes von Kyrene als Mathematiker und Philosoph. Groningen-Djakarta.

- A V Dorofeeva (1988). Eratosthenes (ca. 276-194 B.C.E.). Mat. v Shkole (4): i.

- J Dutka (1993). Eratosthenes' measurement of the Earth reconsidered. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 46 (1): 55 – 66.

- B A El'natanov (1983). A brief outline of the history of the development of the sieve of Eratosthenes. Istor.-Mat. Issled. 27: 238 – 259.

- D H Fowler (1983). Eratosthenes' ratio for the obliquity of the ecliptic. Isis 74 (274): 556 – 562.

- B R Goldstein (1984). Eratosthenes on the "measurement" of the earth. Historia Math. 11 (4): 411 – 416.

- E Gulbekian (1987). The origin and value of the stadion unit used by Eratosthenes in the third century B.C.E. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 37 (4): 359 – 363.

- G Knaack (1907). Eratosthenes. Pauly-Wissowa VI: 358 – 388.

- F Manna (1986). The Pentathlos of ancient science, Eratosthenes, first and only one of the "primes". Atti Accad. Pontaniana (N.S.) 35: 37 – 44.

- A Muwaf and A N Philippou (1981). An Arabic version of Eratosthenes writing on mean proportionals. J. Hist. Arabic Sci. 5 (1 – 2): 174 – 147.

- D Rawlins (1982). Eratosthenes' geodest unraveled : was there a high-accuracy Hellenistic astronomy. Isis 73: 259 – 265.

- D Rawlins (1982). The Eratosthenes - Strabo Nile map. Is it the earliest surviving instance of spherical cartography? Did it supply the 5000 stades arc for Eratosthenes' experiment?. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 26 (3): 211 – 219.

- C M Taisbak (1984). Eleven eighty-thirds. Ptolemy's reference to Eratosthenes in Almagest I.12. Centaurus 27 (2): 165 – 167.

External links

- Bernhardy, Gottfried: "Eratosthenica" Berlin 1822 Reprinted Osnabruck 1968 (German text)

- John J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson. Eratosthenes at the MacTutor archive

- Eratosthenes' sieve in Javascript

- Eratosthenes' sieve as a simple algorithm

- About Eratosthenes' methods, including a Java applet

- How to measure the earth with Eratosthenes' method

- How the Greeks estimated the distances to the moon and sun

- Eratosthenes on PBS.org

- Inter-collegiate project for measuring the earth with Eratosthenes' method

- Measuring the earth with Eratosthenes' method

- List of ancient Greek mathematecians and contemporaries of Eratosthenes

- New Advent Encyclopedia article on the Library of Alexandria

- Eratosthenes' sieve explored and visualised in Flash

- Eratosthenes' sieve in classic BASIC all-web based interactive programming environment

[[zh:埃拉托斯特尼

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Erastosthenes |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Beta |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Greek mathematician, astronomer, and geographer. |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 276 B.C.E. |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Cyrene (in modern-day Libya) |

| DATE OF DEATH | 194 B.C.E. |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Ptolemaic Alexandria |

ar:إراتوستينس ast:Eratóstenes bs:Eratosten bg:Ератостен ca:Eratòstenes cs:Eratosthenés z Kyrény cy:Eratosthenes de:Eratosthenes el:Ερατοσθένης ο Κυρηναίος es:Eratóstenes fr:Ératosthène gl:Eratóstenes ko:에라토스테네스 hr:Eratosten id:Eratosthenes it:Eratostene di Cirene he:ארטוסתנס ka:ერატოსთენე hu:Eratoszthenész (földrajztudós) nl:Eratosthenes ja:エラトステネス no:Eratostenes pms:Eratòstene pl:Eratostenes pt:Eratóstenes ru:Эратосфен sk:Eratostenes sl:Eratosten fi:Eratosthenes sv:Eratosthenes th:Eratosthenes vi:Eratosthenes tr:Eratosthenes uk:Ератосфен zh:埃拉托斯特尼

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.