Difference between revisions of "Drawing and quartering" - New World Encyclopedia

(started) |

Simona Brkic (talk | contribs) m (→References) |

||

| (47 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} |

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Law]] | [[Category:Law]] | ||

| − | + | [[File:Drawing of William de Marisco.jpg|right|thumb|300px|As illustrated in [[Matthew Paris]]'s ''[[Chronica Majora]]'', [[William de Marisco]] is drawn to his execution tied to the back of a horse.]] | |

| − | + | To be '''drawn and quartered''' was the [[penalty]] ordained in [[England]] for the crime of [[treason]]. It is considered by many to be the epitome of [[cruel and unusual punishment|cruel punishment]], and was reserved for the crime of treason as this was deemed more heinous than [[murder]] and other [[Capital punishment|capital offenses]]. The grisly [[punishment]] included the drawing of the convicted to the gallows, often by [[horse]], the [[hanging]] of the body until near death, disembowelment and castration, followed by the [[beheading]] of the body, and finally the quartering of the corpse, or the division of the bodily remnants into four pieces. The punishment was carried out in public, with the ridicule of the crowd adding to the criminal's suffering. This punishment was only applied to male criminals; women found guilty of treason in England were [[Execution by burning|burnt at the stake]]. It was first employed in the thirteenth century and last carried out in 1782, although not abolished until 1867. | |

| − | To be ''' | + | {{toc}} |

| − | [[ | + | This form of punishment was intentionally [[barbarian|barbaric]], as it was employed in days when rulers sought to maintain their position and authority by the most effective means. The most severe punishment, and thus greatest deterrent, was consequently used for treason, since it was the greatest threat to the ruler. Throughout history, rulers have used a variety of ways to instill fear and obedience in their people; drawing and quartering is but one of those. The day is still awaited when those in positions of [[leadership]] find ways to love and care for those for whom they are responsible, thus creating a [[society]] in which threat of barbaric punishment is no longer needed to maintain [[loyalty]]. |

==Details of the punishment== | ==Details of the punishment== | ||

| − | + | [[Execution]] was a highly popular spectator event in [[Elizabeth I|Elizabethan]] [[England]], and served as an effective tool of British [[law enforcement]] to instill fear and crown loyalty within the British public. The entire [[punishment]] process was conducted publicly, at an established market or meeting place, such as [[Tyburn Gallows]], [[Smithfield]], [[Cheapside]], or [[St. Giles]]. Petty criminals usually received the sentence of [[hanging]], while nobles and royalty were subject to [[beheading]]. [[Traitor]]s were to receive the punishment of drawing and quartering, the most barbaric of practices, to send a horrific message to all enemies and potential enemies of the state. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In addition, dismemberment of the body after death was seen by many contemporaries as a way of punishing the traitor beyond the grave. In western [[Europe]]an [[Christian]] countries, it was ordinarily considered contrary to the dignity of the human body to mutilate it. A Parliamentary Act from the reign of [[Henry VIII of England|Henry VIII]] stipulated that only the corpses of executed [[murder]]ers could be used for dissection. Being dismembered was thus viewed as an extra punishment not suitable for others. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Acts of [[treason]] included plotting against the [[monarchy]], planning [[revolution]], giving information to an enemy country, assassinating any political leader, or refusing to acknowledge the official [[church]] of the land. The full punishment for the crime of treason was to first be hanged, then drawn, and quartered. Those convicted would first be dragged by horse or [[hurdle]], a wooden frame, to the place of execution. Victims were subject to the contempt and abuse of the rowdy crowds who gathered to take in the display. The convicted would then be hanged by the neck for a short time or until almost dead. In most cases, the condemned man would be subjected to the short drop method of hanging, so that the neck would not break. He was then dragged alive to the quartering table. | |

| − | + | In cases where men were brought to the table unconscious, a splash of water was used to wake them up. Often the [[disembowelment]] and [[castration]] of the victim would follow, the genitalia and entrails burned before the condemned's eyes. In many cases, the shock of such mutilation killed the victim. Finally the victim would be beheaded and the body divided into four parts, or [[quartered]]. Quartering was sometimes accomplished by tying the body’s limbs to four horses, each horse being spurred away in a different direction. Typically, the resulting parts of the body were [[gibbet]]ed, or put on public display, in different parts of the city, town, or country, to deter potential traitors. The head was commonly sent to the [[Tower of London]]. Gibbeting was abolished in 1843. | |

| − | == | + | ==Class distinctions== |

| − | + | {{readout|In [[Britain]], the penalty of drawing and quartering was usually reserved for commoners, including knights. Noble traitors were merely [[beheading{{!}}beheaded]]|left}}, at first by sword and in later years by axe. The different treatment of lords and commoners was clear after the [[Cornish Rebellion of 1497]]; lowly-born [[Michael An Gof]] and [[Thomas Flamank]] were hanged, drawn, and quartered at [[Tyburn, London|Tyburn]], while their fellow rebellion leader [[James Tuchet, 7th Baron Audley|Lord Audley]] was beheaded at [[Tower Hill]]. | |

| − | + | This class distinction was brought out in a [[British House of Commons|House of Commons]] debate in 1680, with regard to the Warrant of Execution of Lord Stafford, which had condemned him to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. Sir [[William Jones]] is quoted as saying, "Death is the substance of the Judgment; the manner of it is but a circumstance…. No man can show me an example of a Nobleman that has been quartered for High-Treason: They have been only beheaded." The House then resolved that "Execution be done upon Lord Stafford, by severing his Head from his Body."<ref>Anchitell Grey, ''Grey's Debates of the House of Commons: volume 8,'' (London, 1769). </ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Eyewitness account== | |

| + | An account is provided by the diary of [[Samuel Pepys]] for Saturday, October 13, 1660, in which he describes his attendance at the execution of Major-General [[Thomas Harrison]] for regicide. The complete diary entry for the day illustrates the matter-of-fact way in which the [[execution]] is treated by Pepys: | ||

| + | <blockquote>To my Lord's in the morning, where I met with Captain Cuttance, but my Lord not being up I went out to Charing Cross, to see Major-general Harrison hanged, drawn, and quartered; which was done there, he looking as cheerful as any man could do in that condition. He was presently cut down, and his head and heart shown to the people, at which there was great shouts of joy. It is said, that he said that he was sure to come shortly at the right hand of Christ to judge them that now had judged him; and that his wife do expect his coming again. Thus it was my chance to see the King beheaded at White Hall, and to see the first blood shed in revenge for the blood of the King at Charing Cross. From thence to my Lord's, and took Captain Cuttance and Mr. Sheply to the Sun Tavern, and did give them some oysters. After that I went by water home, where I was angry with my wife for her things lying about, and in my passion kicked the little fine basket, which I bought her in Holland, and broke it, which troubled me after I had done it. Within all the afternoon setting up shelves in my study. At night to bed.<ref>Samuel Pepys, Samuel. ''The Diary of Samuel Pepys: A New and Complete Transcription Volume I'' (London: Bell & Hyman, 1993, ISBN 0713515511).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | == | + | ==Noteworthy victims== |

| − | + | Hanging, drawing, and quartering was first invented to punish convicted [[piracy|pirate]] William Maurice in 1241. Such punishment was eventually codified within British law, informing the condemned, “That you be drawn on a hurdle to the place of execution where you shall be hanged by the neck and being alive cut down, your privy members shall be cut off and your bowels taken out and burned before you, your head severed from your body and your body divided into four quarters to be disposed of at the King’s pleasure.”<ref>Capitol Punishment, U.K. [http://www.richard.clark32.btinternet.co.uk/hdq.html Hanging, drawing and quartering.] Retrieved June 14, 2007.</ref> Various Englishman received such a sentence, including over 100 Catholic [[martyr]]s for the "spiritual treason" of refusing to recognize the authority of the [[Anglican]] Church. Some of the more famous cases are listed below. | |

| − | + | ===Prince David of Wales=== | |

| + | The punishment of hanging, drawing, and quartering was more famously and verifiably employed by [[Edward I of England|King Edward I]] in his efforts to bring [[Wales]], [[Scotland]], and [[Ireland]] under English rule. | ||

| − | + | In 1283, hanging, drawing, and quartering was also inflicted on the Welsh prince [[David ap Gruffudd]]. Gruffudd had been a hostage in the English court during his youth, growing up with [[Edward I]] and for several years fighting alongside Edward against his brother [[Llywelyn ap Gruffudd]], the [[Prince of Wales]]. Llywelyn had won recognition of the title, Prince of Wales, from Edward's father [[Henry III of England|King Henry III]], and in 1264, both Edward and his father had been imprisoned by Llywelyn's ally, [[Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester|Simon de Montfort]], the Earl of Leicester. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | Edward's enmity towards Llywelyn ran deep. When David returned to the side of his brother Llywelyn and attacked the English [[Hawarden Castle (medieval)|Hawarden Castle]], Edward saw this as both a personal betrayal and a military setback. His subsequent punishment of David was specifically designed to be harsher than any previous form of [[capital punishment]], and was part of an overarching strategy to eliminate Welsh independence. David was drawn for the crime of [[treason]], hanged for the crime of [[homicide]], disemboweled for the crime of [[sacrilege]], and beheaded and quartered for plotting against the King. When receiving his sentencing, the judge ordered David “to be drawn to the gallows as a traitor to the King who made him a Knight, to be hanged as the murderer of the gentleman taken in the Castle of Hawarden, to have his limbs burnt because he had profaned by assassination the solemnity of Christ's passion and to have his quarters dispersed through the country because he had in different places compassed the death of his lord the king.” David’s head joined that of his brother Llywelyn, killed in a skirmish months earlier, atop the [[Tower of London]], where their skulls were visible for many years. His quartered body parts were sent to four English towns for display. Edward's son, [[Edward II of England|Edward II]], assumed the title [[Prince of Wales]]. | |

| − | + | ===Sir William Wallace=== | |

| + | Perhaps the most infamous sentencing of the punishment was in 1305, against the [[Scotland|Scottish]] patriot [[Sir William Wallace]], a leader during the resistance to the English occupation of Scotland during the wars of [[Scottish independence]]. Eventually betrayed and captured, Wallace was drawn for treason, hanged for homicide, disemboweled for sacrilege, beheaded as an outlaw, and quartered for “divers depredations.” | ||

| − | + | Wallace was tried in Westminster Hall, sentenced, and drawn through the streets to the Tower of London. He was then drawn further to Smithfield where he was hanged but cut down still alive. He suffered a complete emasculation and disembowelment, his genitalia and entrails burnt before him. His heart was then removed from his chest, his body decapitated and quartered. Wallace achieved a great number of victories against the British army, including the [[Battle of Stirling Bridge]] in which he was greatly outnumbered. After his execution, Wallace’s parts were displayed in the towns of [[Newcastle]], [[Berwick]], [[Stirling]], and [[Aberdeen]]. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | ===William Collingbourne=== | |

| + | On October 10, 1484 writer [[William Collingbourne]] was accused of plotting a rebellion against [[King Richard III]] for writing the famous couplet, “The cat, the rat and Lovel our dog, rule all England under the hog.” The apparently innocent rhyme was, in fact, referring to King Richard (the hog) and his three supporters: Richard Ratcliffe (the rat), William Catesby (the cat) and Francis Lovell (the dog). | ||

| − | [[ | + | This writing being regarded as [[treason]], Collingbourne was sentenced to brutal execution by hanging, followed by drawing and quartering while still alive. Of his punishment, English historian [[John Stowe]] wrote, "After having been hanged, he was cut down immediately and his entrails were then extracted and thrown into the fire, and all this was so speedily done that when the executioners pulled out his heart he spoke and said, 'Oh Lord Jesus, yet more trouble!'" |

| − | + | ===English Tudors=== | |

| − | + | In 1535, in an attempt to intimidate the [[Roman Catholic]] clergy to take the [[Oath of Supremacy]], [[Henry VIII of England|Henry VIII]] ordered that [[Saint John Houghton|John Houghton]], the prior of the London Charterhouse, be condemned to be hanged, drawn, and quartered, along with two other [[Carthusians]]. Henry also famously condemned one [[Francis Dereham]] to this form of execution for being one of wife [[Catherine Howard]]'s lovers. Dereham and the King's good friend [[Thomas Culpeper]] were both executed shortly before Catherine herself, but Culpeper was spared the cruel punishment and was instead beheaded. Sir [[Thomas More]], who was found guilty of high [[treason]] under the [[Treason Act 1534|Treason Act of 1534]], was spared this punishment; Henry commuted the execution to one by beheading. | |

| − | |||

| − | In [[ | + | In September of 1586, in the aftermath of the [[Babington plot]] to murder [[Elizabeth I|Queen Elizabeth I]] and replace her on the throne with [[Mary I of Scotland|Mary Queen of Scots]], the conspirators were condemned to drawing and quartering. On hearing of the appalling agony to which the first seven men were subjected, Elizabeth ordered that the remaining conspirators, who were to be dispatched on the following day, should be left hanging until they were dead. Other Elizabethans who were executed in this way include the Catholic priest St [[Edmund Campion]] in 1581, and Elizabeth's own physician [[Rodrigo Lopez (physician)|Rodrigo Lopez]], a Portuguese Jew, who was convicted of conspiring against her in 1594. |

| − | The | + | ===The Gunpowder Conspirators=== |

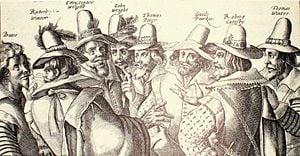

| + | [[Image:Gunpow1.jpg|thumb|300px|left|A contemporary sketch of the Gunpowder Conspirators.]] | ||

| + | In 1606, Catholic conspirator [[Guy Fawkes]] and several co-conspirators were sentenced to drawing and quartering after a failed attempt to assassinate King [[James I of England|James I]]. The plan, known as the [[Gunpowder Plot]], was to blow up the [[Houses of Parliament]] at [[Westminster]] using barrels of [[gunpowder]]. On the day of his execution, Fawkes, though weakened by [[torture]], cheated the executioners when he jumped from the gallows, breaking his neck and dying before his disembowelment. Co-conspirator [[Robert Keyes]] attempted the same trick; however the rope broke and he was drawn fully conscious. In May of 1606, English Jesuit [[Henry Garnet]] was executed at London’s [[St Paul's Cathedral]]. His crime was to be the [[confessor]] of several members of the Gunpowder Plot. Many spectators thought that the sentence too severe, and "With a loud cry of 'hold, hold' they stopped the hangman cutting down the body while Garnet was still alive. Others pulled the priest's legs … which was traditionally done to ensure a speedy death".<ref>Antonia Fraser, ''Faith and Treason: The Story of the Gunpowder Plot,'' (Anchor, 1997 ISBN 0385471904).</ref> | ||

| − | == | + | ===Other cases=== |

| − | In | + | In 1676, Joshua Tefft was executed by drawing and quartering at Smith's Castle in Wickford, [[Rhode Island]]. An English colonist who fought on the side of the [[Narragansett (tribe)|Narragansett]] during the battle of [[King Philip's War]]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In 1681, [[Oliver Plunkett]], [[Archbishop of Armagh (Roman Catholic)|Archbishop of Armagh]] and the Catholic [[Primate (religion)|primate]] of [[Ireland]], was arrested and transported to [[Newgate Prison]], London, where he was convicted of [[treason]]. He was hanged, drawn, and quartered at [[Tyburn, London|Tyburn]], the last Catholic to be executed for his faith in England. In 1920, Plunkett was [[beatification|beatified]] and in 1975 [[canonization|canonized]] by [[Pope Paul VI]]. His head is preserved for viewing as a relic in St. Peter's Church in [[Drogheda]], while the rest of his body rests in [[Downside Abbey]], near [[Stratton-on-the-Fosse]], [[Somerset]]. | |

| − | + | In July 1781, the penultimate drawing and quartering was carried out against the French [[spy]] [[François Henri de la Motte]], who was convicted of treason. The last time any man was drawn and quartered was in August 1782. The victim, Scottish spy [[David Tyrie]], was executed in [[Portsmouth]] for carrying on a treasonable correspondence with the French. A contemporary account in the ''Hampshire Chronicle'' describes his being hanged for 22 minutes, following which he was beheaded and his heart cut out and burned. He was then [[emasculation|emasculated]], quartered, and his body parts put into a [[coffin]] and buried in the pebbles at the seaside. The same account claims that immediately after his burial, sailors dug the coffin up and cut the body into a thousand pieces, each taking a piece as a [[souvenir]] to their shipmates.<ref>Hampshire Chronicle. [http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com/~dutillieul/ZOtherPapers/HCSep21782.html Other Papers.] ''Hampshire Chronicle.'' (1782). Retrieved June 25, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | In 1803, British revolutionary Edward Marcus Despard and six accomplices were sentenced to be drawn, hanged, and quartered for [[conspiracy]] against [[King George III]]; however their sentences were reduced to simple hanging and beheading. The last to receive this sentence were two Irish Fenians, Burke and O’Brien, in 1867; however, the punishment was not carried out. | |

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 132: | Line 67: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | *Fraser, Antonia. ''Faith and Treason: The Story of the Gunpowder Plot''. Anchor, 1997. ISBN 0385471904 | ||

| + | *Grey, Anchitell. ''Grey's Debates of the House of Commons: Volume 8''. London, 1769. | ||

| + | *Jay, Mike. ''The Unfortunate Colonel Despard: The Tragic True Story of the Last Man Condemned to Be Hung, Drawn and Quartered.'' Doubleday, 2005. ISBN 055381608X | ||

| + | *Pepys, Samuel. ''The Diary of Samuel Pepys: A New and Complete Transcription Volume I''. London: Bell & Hyman, 1993. ISBN 0713515511 | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credits|Hanged,_drawn_and_quartered|135572998|}} | {{Credits|Hanged,_drawn_and_quartered|135572998|}} | ||

Latest revision as of 19:19, 14 August 2020

To be drawn and quartered was the penalty ordained in England for the crime of treason. It is considered by many to be the epitome of cruel punishment, and was reserved for the crime of treason as this was deemed more heinous than murder and other capital offenses. The grisly punishment included the drawing of the convicted to the gallows, often by horse, the hanging of the body until near death, disembowelment and castration, followed by the beheading of the body, and finally the quartering of the corpse, or the division of the bodily remnants into four pieces. The punishment was carried out in public, with the ridicule of the crowd adding to the criminal's suffering. This punishment was only applied to male criminals; women found guilty of treason in England were burnt at the stake. It was first employed in the thirteenth century and last carried out in 1782, although not abolished until 1867.

This form of punishment was intentionally barbaric, as it was employed in days when rulers sought to maintain their position and authority by the most effective means. The most severe punishment, and thus greatest deterrent, was consequently used for treason, since it was the greatest threat to the ruler. Throughout history, rulers have used a variety of ways to instill fear and obedience in their people; drawing and quartering is but one of those. The day is still awaited when those in positions of leadership find ways to love and care for those for whom they are responsible, thus creating a society in which threat of barbaric punishment is no longer needed to maintain loyalty.

Details of the punishment

Execution was a highly popular spectator event in Elizabethan England, and served as an effective tool of British law enforcement to instill fear and crown loyalty within the British public. The entire punishment process was conducted publicly, at an established market or meeting place, such as Tyburn Gallows, Smithfield, Cheapside, or St. Giles. Petty criminals usually received the sentence of hanging, while nobles and royalty were subject to beheading. Traitors were to receive the punishment of drawing and quartering, the most barbaric of practices, to send a horrific message to all enemies and potential enemies of the state.

In addition, dismemberment of the body after death was seen by many contemporaries as a way of punishing the traitor beyond the grave. In western European Christian countries, it was ordinarily considered contrary to the dignity of the human body to mutilate it. A Parliamentary Act from the reign of Henry VIII stipulated that only the corpses of executed murderers could be used for dissection. Being dismembered was thus viewed as an extra punishment not suitable for others.

Acts of treason included plotting against the monarchy, planning revolution, giving information to an enemy country, assassinating any political leader, or refusing to acknowledge the official church of the land. The full punishment for the crime of treason was to first be hanged, then drawn, and quartered. Those convicted would first be dragged by horse or hurdle, a wooden frame, to the place of execution. Victims were subject to the contempt and abuse of the rowdy crowds who gathered to take in the display. The convicted would then be hanged by the neck for a short time or until almost dead. In most cases, the condemned man would be subjected to the short drop method of hanging, so that the neck would not break. He was then dragged alive to the quartering table.

In cases where men were brought to the table unconscious, a splash of water was used to wake them up. Often the disembowelment and castration of the victim would follow, the genitalia and entrails burned before the condemned's eyes. In many cases, the shock of such mutilation killed the victim. Finally the victim would be beheaded and the body divided into four parts, or quartered. Quartering was sometimes accomplished by tying the body’s limbs to four horses, each horse being spurred away in a different direction. Typically, the resulting parts of the body were gibbeted, or put on public display, in different parts of the city, town, or country, to deter potential traitors. The head was commonly sent to the Tower of London. Gibbeting was abolished in 1843.

Class distinctions

In Britain, the penalty of drawing and quartering was usually reserved for commoners, including knights. Noble traitors were merely beheaded, at first by sword and in later years by axe. The different treatment of lords and commoners was clear after the Cornish Rebellion of 1497; lowly-born Michael An Gof and Thomas Flamank were hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn, while their fellow rebellion leader Lord Audley was beheaded at Tower Hill.

This class distinction was brought out in a House of Commons debate in 1680, with regard to the Warrant of Execution of Lord Stafford, which had condemned him to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. Sir William Jones is quoted as saying, "Death is the substance of the Judgment; the manner of it is but a circumstance…. No man can show me an example of a Nobleman that has been quartered for High-Treason: They have been only beheaded." The House then resolved that "Execution be done upon Lord Stafford, by severing his Head from his Body."[1]

Eyewitness account

An account is provided by the diary of Samuel Pepys for Saturday, October 13, 1660, in which he describes his attendance at the execution of Major-General Thomas Harrison for regicide. The complete diary entry for the day illustrates the matter-of-fact way in which the execution is treated by Pepys:

To my Lord's in the morning, where I met with Captain Cuttance, but my Lord not being up I went out to Charing Cross, to see Major-general Harrison hanged, drawn, and quartered; which was done there, he looking as cheerful as any man could do in that condition. He was presently cut down, and his head and heart shown to the people, at which there was great shouts of joy. It is said, that he said that he was sure to come shortly at the right hand of Christ to judge them that now had judged him; and that his wife do expect his coming again. Thus it was my chance to see the King beheaded at White Hall, and to see the first blood shed in revenge for the blood of the King at Charing Cross. From thence to my Lord's, and took Captain Cuttance and Mr. Sheply to the Sun Tavern, and did give them some oysters. After that I went by water home, where I was angry with my wife for her things lying about, and in my passion kicked the little fine basket, which I bought her in Holland, and broke it, which troubled me after I had done it. Within all the afternoon setting up shelves in my study. At night to bed.[2]

Noteworthy victims

Hanging, drawing, and quartering was first invented to punish convicted pirate William Maurice in 1241. Such punishment was eventually codified within British law, informing the condemned, “That you be drawn on a hurdle to the place of execution where you shall be hanged by the neck and being alive cut down, your privy members shall be cut off and your bowels taken out and burned before you, your head severed from your body and your body divided into four quarters to be disposed of at the King’s pleasure.”[3] Various Englishman received such a sentence, including over 100 Catholic martyrs for the "spiritual treason" of refusing to recognize the authority of the Anglican Church. Some of the more famous cases are listed below.

Prince David of Wales

The punishment of hanging, drawing, and quartering was more famously and verifiably employed by King Edward I in his efforts to bring Wales, Scotland, and Ireland under English rule.

In 1283, hanging, drawing, and quartering was also inflicted on the Welsh prince David ap Gruffudd. Gruffudd had been a hostage in the English court during his youth, growing up with Edward I and for several years fighting alongside Edward against his brother Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, the Prince of Wales. Llywelyn had won recognition of the title, Prince of Wales, from Edward's father King Henry III, and in 1264, both Edward and his father had been imprisoned by Llywelyn's ally, Simon de Montfort, the Earl of Leicester.

Edward's enmity towards Llywelyn ran deep. When David returned to the side of his brother Llywelyn and attacked the English Hawarden Castle, Edward saw this as both a personal betrayal and a military setback. His subsequent punishment of David was specifically designed to be harsher than any previous form of capital punishment, and was part of an overarching strategy to eliminate Welsh independence. David was drawn for the crime of treason, hanged for the crime of homicide, disemboweled for the crime of sacrilege, and beheaded and quartered for plotting against the King. When receiving his sentencing, the judge ordered David “to be drawn to the gallows as a traitor to the King who made him a Knight, to be hanged as the murderer of the gentleman taken in the Castle of Hawarden, to have his limbs burnt because he had profaned by assassination the solemnity of Christ's passion and to have his quarters dispersed through the country because he had in different places compassed the death of his lord the king.” David’s head joined that of his brother Llywelyn, killed in a skirmish months earlier, atop the Tower of London, where their skulls were visible for many years. His quartered body parts were sent to four English towns for display. Edward's son, Edward II, assumed the title Prince of Wales.

Sir William Wallace

Perhaps the most infamous sentencing of the punishment was in 1305, against the Scottish patriot Sir William Wallace, a leader during the resistance to the English occupation of Scotland during the wars of Scottish independence. Eventually betrayed and captured, Wallace was drawn for treason, hanged for homicide, disemboweled for sacrilege, beheaded as an outlaw, and quartered for “divers depredations.”

Wallace was tried in Westminster Hall, sentenced, and drawn through the streets to the Tower of London. He was then drawn further to Smithfield where he was hanged but cut down still alive. He suffered a complete emasculation and disembowelment, his genitalia and entrails burnt before him. His heart was then removed from his chest, his body decapitated and quartered. Wallace achieved a great number of victories against the British army, including the Battle of Stirling Bridge in which he was greatly outnumbered. After his execution, Wallace’s parts were displayed in the towns of Newcastle, Berwick, Stirling, and Aberdeen.

William Collingbourne

On October 10, 1484 writer William Collingbourne was accused of plotting a rebellion against King Richard III for writing the famous couplet, “The cat, the rat and Lovel our dog, rule all England under the hog.” The apparently innocent rhyme was, in fact, referring to King Richard (the hog) and his three supporters: Richard Ratcliffe (the rat), William Catesby (the cat) and Francis Lovell (the dog).

This writing being regarded as treason, Collingbourne was sentenced to brutal execution by hanging, followed by drawing and quartering while still alive. Of his punishment, English historian John Stowe wrote, "After having been hanged, he was cut down immediately and his entrails were then extracted and thrown into the fire, and all this was so speedily done that when the executioners pulled out his heart he spoke and said, 'Oh Lord Jesus, yet more trouble!'"

English Tudors

In 1535, in an attempt to intimidate the Roman Catholic clergy to take the Oath of Supremacy, Henry VIII ordered that John Houghton, the prior of the London Charterhouse, be condemned to be hanged, drawn, and quartered, along with two other Carthusians. Henry also famously condemned one Francis Dereham to this form of execution for being one of wife Catherine Howard's lovers. Dereham and the King's good friend Thomas Culpeper were both executed shortly before Catherine herself, but Culpeper was spared the cruel punishment and was instead beheaded. Sir Thomas More, who was found guilty of high treason under the Treason Act of 1534, was spared this punishment; Henry commuted the execution to one by beheading.

In September of 1586, in the aftermath of the Babington plot to murder Queen Elizabeth I and replace her on the throne with Mary Queen of Scots, the conspirators were condemned to drawing and quartering. On hearing of the appalling agony to which the first seven men were subjected, Elizabeth ordered that the remaining conspirators, who were to be dispatched on the following day, should be left hanging until they were dead. Other Elizabethans who were executed in this way include the Catholic priest St Edmund Campion in 1581, and Elizabeth's own physician Rodrigo Lopez, a Portuguese Jew, who was convicted of conspiring against her in 1594.

The Gunpowder Conspirators

In 1606, Catholic conspirator Guy Fawkes and several co-conspirators were sentenced to drawing and quartering after a failed attempt to assassinate King James I. The plan, known as the Gunpowder Plot, was to blow up the Houses of Parliament at Westminster using barrels of gunpowder. On the day of his execution, Fawkes, though weakened by torture, cheated the executioners when he jumped from the gallows, breaking his neck and dying before his disembowelment. Co-conspirator Robert Keyes attempted the same trick; however the rope broke and he was drawn fully conscious. In May of 1606, English Jesuit Henry Garnet was executed at London’s St Paul's Cathedral. His crime was to be the confessor of several members of the Gunpowder Plot. Many spectators thought that the sentence too severe, and "With a loud cry of 'hold, hold' they stopped the hangman cutting down the body while Garnet was still alive. Others pulled the priest's legs … which was traditionally done to ensure a speedy death".[4]

Other cases

In 1676, Joshua Tefft was executed by drawing and quartering at Smith's Castle in Wickford, Rhode Island. An English colonist who fought on the side of the Narragansett during the battle of King Philip's War.

In 1681, Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh and the Catholic primate of Ireland, was arrested and transported to Newgate Prison, London, where he was convicted of treason. He was hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn, the last Catholic to be executed for his faith in England. In 1920, Plunkett was beatified and in 1975 canonized by Pope Paul VI. His head is preserved for viewing as a relic in St. Peter's Church in Drogheda, while the rest of his body rests in Downside Abbey, near Stratton-on-the-Fosse, Somerset.

In July 1781, the penultimate drawing and quartering was carried out against the French spy François Henri de la Motte, who was convicted of treason. The last time any man was drawn and quartered was in August 1782. The victim, Scottish spy David Tyrie, was executed in Portsmouth for carrying on a treasonable correspondence with the French. A contemporary account in the Hampshire Chronicle describes his being hanged for 22 minutes, following which he was beheaded and his heart cut out and burned. He was then emasculated, quartered, and his body parts put into a coffin and buried in the pebbles at the seaside. The same account claims that immediately after his burial, sailors dug the coffin up and cut the body into a thousand pieces, each taking a piece as a souvenir to their shipmates.[5]

In 1803, British revolutionary Edward Marcus Despard and six accomplices were sentenced to be drawn, hanged, and quartered for conspiracy against King George III; however their sentences were reduced to simple hanging and beheading. The last to receive this sentence were two Irish Fenians, Burke and O’Brien, in 1867; however, the punishment was not carried out.

Notes

- ↑ Anchitell Grey, Grey's Debates of the House of Commons: volume 8, (London, 1769).

- ↑ Samuel Pepys, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Pepys: A New and Complete Transcription Volume I (London: Bell & Hyman, 1993, ISBN 0713515511).

- ↑ Capitol Punishment, U.K. Hanging, drawing and quartering. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- ↑ Antonia Fraser, Faith and Treason: The Story of the Gunpowder Plot, (Anchor, 1997 ISBN 0385471904).

- ↑ Hampshire Chronicle. Other Papers. Hampshire Chronicle. (1782). Retrieved June 25, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fraser, Antonia. Faith and Treason: The Story of the Gunpowder Plot. Anchor, 1997. ISBN 0385471904

- Grey, Anchitell. Grey's Debates of the House of Commons: Volume 8. London, 1769.

- Jay, Mike. The Unfortunate Colonel Despard: The Tragic True Story of the Last Man Condemned to Be Hung, Drawn and Quartered. Doubleday, 2005. ISBN 055381608X

- Pepys, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Pepys: A New and Complete Transcription Volume I. London: Bell & Hyman, 1993. ISBN 0713515511

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.