Brazil nut

| Brazil nut | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Bertholletia excelsa Humb. & Bonpl. |

Brazil nut is the common name for a large, South American tree, Bertholletia excelsa, in the family Lecythidaceae, characterized by a large, hard, woody, spherical coconut-like seed pod, or fruit, containing a number of dark brown, triangular (three-sided) seeds with a extremely hard shell, known as "nuts," each with a whitish kernal inside. The term brazil nut also is used for the edible seed, which is of commercially importance.

- Ecologically: harmony in nature.. Brazil nut trees produce fruit almost exclusively in pristine forests, as disturbed forests lack the large-body bees of the genera Bombus, Centris, Epicharis, Eulaema, and Xylocopa which are the only ones capable of pollinating the tree's flowers

The capsule contains a small hole at one end, which enables large rodents like the agouti to gnaw it open. They then eat some of the nuts inside while burying others for later use; some of these are able to germinate to produce new Brazil nut trees. The agouti may carry a seed over 400 meters from the parent tree (Hennessey 2001). Most of the seeds are "planted" by the agoutis in shady places, and the young saplings may have to wait years, in a state of dormancy, for a tree to fall and sunlight to reach it. It is not until then that it starts growing again. Capuchin monkeys have been reported to open Brazil nuts using a stone as an anvil.

Overview and description

.

The brazil nut tree is the only species in the monotypic genus Bertholletia. The Lecythidaceae family to which it belongs contains about 20 genera and 250 to 300 species of woody plants native to tropical South America and Madagascar. The Brazil nut, Bertholletia excelsa, is native to Brazil, eastern Bolivia, the Guianas, Venezuela, eastern Colombia, and eastern Peru. It occurs as scattered trees in large forests on the banks of the Amazon, Rio Negro, and the Orinoco. The genus is named after the French chemist Claude Louis Berthollet.

The brazil nut is a large tree, reaching 30 to 45 meters (100 to 150 feet) tall and 1 to 2 meters (3–6.5 feet) in trunk diameter, among the largest of trees in the Amazon Rainforest. The stem is straight and commonly unbranched for well over half the tree's height, with a large emergent crown of long branches above the surrounding canopy of other trees. The bark is grayish and smooth. The stem may live for 500 years or more, and according to some authorities often reaches an age of 1,000 years (Taitson 2007).

TThe leaves are dry-season deciduous, alternate, simple, entire or crenate, oblong, 20 to 35 centimeters (8-14 inches) long and 10 to 15 centimeters (4-6 inches) broad. The flowers are small, greenish-white, in panicles 5 to 10 centimeters (2-4 inches) long; each flower has a two-parted, deciduous calyx, six unequal cream-colored petals, and numerous stamens united into a broad, hood-shaped mass.

Fruit and reproduction

Brazil nut trees produce fruit almost exclusively in pristine forests, as disturbed forests lack the large-body bees that are the only ones capable of pollinating the tree's flowers (Nelson et al. 1985; Moritz 1984). Brazil nuts have been harvested from plantations but production is low and it is currently not economically viable (Hennessey 2001; Kirchgessner).

The brazil nut tree's yellow flowers contain very sweet nectar and can only be pollinated by an insect strong enough to lift the coiled hood on the flower and with tongues long enough to negotiate the complex coiled flower. Notably, the flowers produce a scent that attracts large-bodied, long-tongued euglossine bees, or orchid bees. Small male orchid bees are attracted to the flowers, as the male bees need that scent to attract females. But is is largely the large female long-tongued orchid bee that actually pollinates the Brazil nut tree (Hennessey 2001). Without the flowers, the bees do not mate, and the lack of bees means the fruit does not get pollinated.

Among species of large-bodied bees, orchid bees or not, observed to visit the flowers are those of the genera Eulaema, Bombus, Centris, Epicharis, and Xylocopa (Kirchgessner).

If both the orchids and the bees are present, the fruit takes 14 months to mature after pollination of the flowers. The fruit itself is a large capsule 10 to 15 centimeters diameter resembling a coconut endocarp in size and weighing up to 2 to 3 kilograms. It has a hard, woody shell 8 to 12 millimeter thick. Inside this hard, round, seedpod, are 8 to 24 triangular (three-sided) seeds about 4 to 5 centimeters (1.5-2 inches) long (the "Brazil nuts") packed like the segments of an orange; it is not a true nut in the botanical sense, but only in the culinary sense.

The capsule contains a small hole at one end, which enables large rodents like the agouti to gnaw it open. They then eat some of the nuts inside while burying others for later use; some of these are able to germinate to produce new Brazil nut trees. The agouti may carry a seed over 400 meters from the parent tree (Hennessey 2001). Most of the seeds are "planted" by the agoutis in shady places, and the young saplings may have to wait years, in a state of dormancy, for a tree to fall and sunlight to reach it. It is not until then that it starts growing again. Capuchin monkeys have been reported to open Brazil nuts using a stone as an anvil.

Nomenclature

Despite their name, the most significant exporter of brazil nuts is not Brazil but Bolivia, where they are called almendras. In Brazil these nuts are called castanhas-do-Pará (literally "chestnuts from Pará"), but Acreans call them castanhas-do-Acre instead. Indigenous names include juvia in the Orinoco area, and sapucaia in the rest of Brazil.

Cream nuts is one of the several historical names used for Brazil nuts in America.

Nut production

Around 20,000 metric tons of Brazil nuts are harvested each year, of which Bolivia accounts for about fifty percent, Brazil about forty percent, and Peru about ten percent (2000 estimates) (Collinson et al. 2000). In 1980, annual production was around 40,000 tons per year from Brazil alone, and in 1970 Brazil harvested a reported 104,487 tons of nuts (Mori 1992).

Brazil nuts for international trade come entirely from wild collection rather than from plantations. This has been advanced as a model for generating income from a tropical forest without destroying it. The nuts largely are gathered by migrant workers.

Analysis of tree ages in areas that are harvested show that moderate and intense gathering takes so many seeds that not enough are left to replace older trees as they die. Sites with light gathering activities had many young trees, while sites with intense gathering practices had hardly any young trees (Silvertown 2004). Statistical tests were done to determine what environmental factors could be contributing to the lack of younger trees. The most consistent effect was found to be the level of gathering activity at a particular site. A computer model predicting the size of trees where people picked all the nuts matched the tree size data that was gathered from physical sites that had heavy harvesting.

Uses

Nutrition

Brazil nuts are about 18% protein, 13% carbohydrates, and 69% fat. The fat breakdown is roughly 25% saturated, 41% monounsaturated, and 34% polyunsaturated (USDA 2008). The saturated fat content of Brazil nuts is among the highest of all nuts.

Nutritionally, Brazil nuts are a good source of magnesium and thiamine[citation needed], and are perhaps the richest dietary source of selenium, containing as much as 1180% of the USRDA (U.S. Recommended Dietary Allowances), although the amount of selenium within batches of nuts varies greatly.[1] Recent research suggests that proper selenium intake is correlated with a reduced risk of both breast cancer as well as prostate cancer.[2] This has led some commentatorsTemplate:Ww to recommend the consumption of Brazil nuts as a protective measure.[3] These findings are inconclusive, however; other investigations into the effects of selenium on prostate cancer were inconclusive.[4]

Despite the possible health benefits of the nut, the European Union has imposed strict regulations on the import from Brazil of Brazil nuts in their shells, as the shells have been found to contain high levels of aflatoxins, which can lead to liver cancer.[5] According to Tony Farndell, MD of TFR Nuts and Dried Fruits Ltd, a UK importer, the import restrictions on in-shell kernels came as a result of the whole nut including the shell, being ground down for testing. Thus aflatoxins were detected and the restrictions imposed.

Brazil nuts also contain small amounts of radioactive radium. Although the amount of radium is very small, about 1–7 pCi/g (40–260 Bq/kg), and most of it is not retained by the body, this is 1,000 times higher than in other foods. According to Oak Ridge Associated Universities, this is not because of elevated levels of radium in the soil, but due to "the very extensive root system of the tree."[6]

Other uses

As well as its food use, Brazil nut oil is also used as a lubricant in clocks, for making artists' paints, and in the cosmetics industry.

The timber from Brazil nut trees (not to be confused with Brazilwood) is of excellent quality, but logging the trees is prohibited by law in all three producing countries (Brazil, Bolivia and Peru). Illegal extraction of timber and land clearances present a continuing threat.[7]

The Brazil nut effect describes the tendency of the larger items to rise to the top of a mixture of items of various sizes but similar densities, e.g., Brazil nuts mixed with peanuts.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Collinson, C., D. Burnett, and V. Agreda. 2000. [8] Natural Resources and Ethical Trade Program, natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich,

[9] 1992

The New York Botanical Garden with the assistance of Anthony Kirchgessner [10]

[11] The Brazil Nut (Bertholletia excelsa) By Tim Hennessey 2001

Jonathan Silvertown http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.03.022 Sustainability in a nutshell Trends in Ecology & Evolution Volume 19, Issue 6, June 2004, Pages 276-278

External links

- INC, International Nut and Dried Fruit Council Foundation

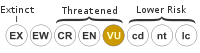

- Americas Regional Workshop (Conservation & Sustainable Management of Trees, Costa Rica, November 1996) 1998. [1]. 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species., World Conservation Union. Retrieved on 9 May 2006. Listed as Vulnerable (VU A1acd+2cd v2.3)

- Peres, C.A. et al. (2003). Demographic threats to the sustainability of Brazil nut exploitation. Science 302 (December 19): 2112–2114. (Overharvesting of Brazil nuts as threat to regeneration.)

- Brazil Nut homepage

- New York Botanical Gardens Brazil Nuts Page

- Brazil nuts' path to preservation, BBC News.

- Brazil nut, The Encyclopedia of Earth

- [2]

- Template loop detected: Template:Grocers

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Chang, Jacqueline C. and Walter H. Gutenmann, Charlotte M. Reid, Donald J. Lisk (1995). Selenium content of Brazil nuts from two geographic locations in Brazil. Chemosphere 30 (4): 801–802. 0045-6535.

- ↑ Klein EA, Thompson IM, Lippman SM, Goodman PJ, Albanes D, Taylor PR, Coltman C., "SELECT: the next prostate cancer prevention trial. Selenum and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial.", J Urol. 2001 Oct;166(4):1311-5. [PMID 11547064]

- ↑ Cancer Decisions Newsletter Archive, Selenium, Brazil Nuts and Prostate Cancer, [3] last accessed 8 March 2007

- ↑ Peters U, Foster CB, Chatterjee N, Schatzkin A, Reding D, Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Sturup S, Chanock SJ, Hayes RB. "Serum selenium and risk of prostate cancer-a nested case-control study." Am J Clin Nutr. 2007 Jan;85(1):209-17. [PMID 17209198]

- ↑ "Commission decision of 4 July 2003 imposing special conditions on the import of Brazil nuts in shell originating in or consigned from Brazil", Official Journal of the European Union, at Food Safety Authority of Ireland website

- ↑ Radioactivity of Brazil nuts. http://www.orau.org/PTP/collection/consumer%20products/brazilnuts.htm

- ↑ Activists Trapped by Loggers in Amazon, Greenpeace, 18 October 2007

- ↑ Economic Viability of Brazil Nut Trading in Peru Chris Collinson et al, University of Greenwich

- ↑ The Brazil Nut Industry — Past, Present, and Future, Scott A. Mori, The New York Botanical Garden

- ↑ Brazil Nut Plantations

- ↑ The Brazil Nut (Bertholletia excelsa)

- ↑ Nelson, B.W. and Absy, M.L.; Barbosa, E.M.; Prance, G.T. (1985). Observations on flower visitors to Bertholletia excelsa H. B. K. and Couratari tenuicarpa A. C. Sm.(Lecythidaceae).. Acta Amazonica 15 (1): 225–234.

- ↑ Moritz, A. (1984). Estudos biológicos da floração e da frutificação da castanha-do-Brasil (Bertholletia excelsa HBK) 29.

- ↑ Harvesting nuts, improving lives in Brazil, Bruno Taitson, WWF, 18 January 2007

- ↑ "USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, release 21 (2008)", United States Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Research Service