Bivalve

| Bivalve | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

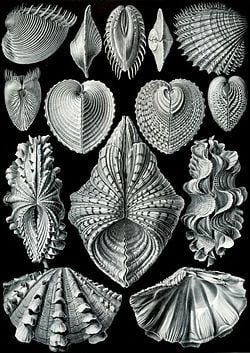

"Acephala" from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur, 1904

| ||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||

| ||||||

|

Subclass Anomalosdesmata

Subclass Heterodonta - clams, zebra mussels

Subclass Paleoheterodonta

Subclass Protobranchia

Subclass Pteriomorphia - oysters, mussels

|

Bivalves are aquatic mollusks belonging to the class Bivalvia ("two valves")—also referred to as class Pelecypoda ("hatchet-foot")—a group that includes the familiar and economically important clams, oysters, scallops, and mussels. Bivalvia refers to the fact that most members of this group have two-part calcareous shells (valves) that are hinged and more or less symmetrical. Pelecypoda refers to the laterally compressed muscular foot that when extended into sediment (sand or mud), can swell with blood and form a hatchet-shaped anchor (Towle 1989). Other names for the class include Bivalva and Lamellibranchia

The class has about 30,000 species, making them the second most diverse class of mollusks after Gastropoda ("univalves"). There are both marine and freshwater forms. Most bivalves are relatively sedentary suspension feeders, although they have various levels of activity, including usng the foot to move; some that can swim by waving the foot or tentacles; and some that can jet-propel themselves by rapidly clapping the shell valves together (reference 2003).

Cephalopods are characterized by bilateral body symmetry,

Bivalves lack a radula and feed by siphoning and filtering large particles from water. Some bivalves are epifaunal: that is, they attach themselves to surfaces in the water, by means of a byssus or organic cementation. Others are infaunal: they bury themselves in sand or other sediments. These forms typically have a strong digging foot. Some bivalves can swim.

Anatomy

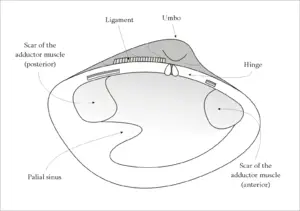

As with all mollusks, bivalves are characterized by having a true coelom; a body divided into the three parts of head, visceral mass, and muscular foot; and organ systems for circulation, respiration, digestion, excretion, nerve conduction, and reproduction (Towle 1989). However, the head is much reduced and not very distinct.

Bivalves are filter-feeders that use their gills to extract organic matter from the water in which they live. They have an open circulatory system that bathes the organs in hemolymph. Nephridia remove the waste material. Bivalves are laterally compressed and have a shell composed of two valves. The valved shell makes them superficially similar to brachiopods, but the construction of the shell is completely different in the two groups: in brachiopods, the two valves are on the upper and lower surfaces of the body, while in bivalves, they are on the left and right sides.

History

Bivalves appeared late in the Cambrian explosion and came to dominate over brachiopods during the Palaeozoic; indeed, by the end-Permian extinction, bivalves were undergoing a huge radiation in numbers while brachiopods (along with ~95% of all species) were devastated.

This raises two questions: how did the bivalves come to challenge the brachiopoda niche before the extinction event, and how did the bivalves escape the fate of extinction? Although inevitable biases exist in the fossil record and our documentation thereof, bivalves essentially appear to be better adapted to aquatic life. Far more sophisticated than the brachiopods, bivalves use an energetically-efficient ligament-muscle system for opening valves, and thus require less food to subsist. Furthermore, their ability to burrow allows for evasion of predators: buried bivalves feed by extending a siphon to the surface (indicated by the presence of a palial sinus, the size of which is proportional to the burrowing depth, and represented by their dentition). Additionally, bivalves became mobile: some developed spines for buoyancy, while others suck in and eject water to enable propulsion. This allowed bivalves to themselves become predators.

With such a wide range of adaptations it is unsurprising that the shapes of bivalve shells vary greatly - some are rounded and globular, others are flattened and plate-like, while still others, such as the razor shell Ensis, have become greatly elongated in order to aid burrowing byssonychia. The shipworms of the family Teredinidae have elongated bodies, but the shell valves are much reduced and restricted to the anterior end of the body. They function as burrowing organs, allowing the animal to dig tunnels through wood.

Some pelecypods are alive today in the Great Sea and the Black Sea. Various Eurasian countries rely on them for food.

External links

- Museum of Paleontology - Palaeontology from the University of California, Berkeley

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.