Mariette, Auguste

(Claimed) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (24 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Anthropologists]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Archaeologists]] |

| − | {{ | + | {{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | {{epname}} | + | {{epname|Mariette, Auguste}} |

| + | [[Image:Auguste Mariette statue, Boulogne-sur-Mer.jpg|thumb|A statue of Auguste Mariette in his home city of Boulogne-sur-Mer.]] | ||

| − | + | '''François Auguste Ferdinand Mariette''' (February 11, 1821 – January 19, 1881) was a [[France|French]] scholar and [[archaeology|archaeologist]], one of the early pioneers of [[Egyptology]]. He became famous for his discoveries at [[Saqqara]], the vast, ancient [[burial]] ground in Memphis, capital of [[Ancient Egypt]]. There he uncovered the Avenue of the [[Sphinx]]es and the [[Serapeum]], an ancient [[temple]] and [[cemetery]] of the sacred Apis bulls. Although originally sent to [[Egypt]] under the auspices of the French government, and thus obliged to send his findings to France for display in the [[Louvre]], Mariette believed that the findings should remain in Egypt. He accepted a permanent position in Egypt and spent the rest of his life there, securing a [[monopoly]] on excavation. He founded of the Egyptian Museum in [[Cairo]], which became the foremost repository of Egyptian antiquities. Mariette's work was significant in opening the field of Egyptology, bringing knowledge of this dominant, somewhat mysterious, early [[civilization]] to the West, while at the same time advocating for the right of the Egyptian nation to retain ownership of its own historical artifacts. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| + | ==Biography== | ||

| − | |||

===Early career=== | ===Early career=== | ||

| − | + | François Auguste Ferdinand Mariette was born at Boulogne-sur-Mer, [[France]], where his father was a town clerk. His first exposure to [[Egypt]] came in 1827, when he was only six years old. At the age of 12 he was already able to read [[ancient Egypt|ancient Egyptian]] [[hieroglyph]]s and decipher [[Coptic language|Coptic]] writings. When his cousin Nestor L'Hote, the friend and fellow-traveler of [[Jean-François Champollion|Champollion]] died, the task of sorting his papers filled Mariette with a passion for [[Egyptology]]. | |

| − | + | His 1847 analytic catalogue of the Egyptian Gallery of the Boulogne Museum led to a minor appointment at the [[Louvre Museum]] in 1849. He supplemented his salary as a [[teacher]] at Douai by giving private lessons and writing on [[history|historical]] and [[archaeology|archaeological]] subjects for local [[periodical]]s. | |

| − | === | + | ===Beginnings in Egypt=== |

| − | + | In 1849, the [[Louvre]] sent Mariette to [[Egypt]] to acquire [[Coptic language|Coptic]], [[Ge’ez language|Ethiopic]], and [[Syriac language|Syriac]] [[manuscript]]s to add to their collection. The acquisition of Egyptian artifacts by national and private collections was then a competitive endeavor, the [[England|English]] being able to pay higher prices. Mariette arrived in Egypt in 1850. | |

| + | [[Image:Saqqarah 082005.JPG|thumb|250 px|left|View of the entrance of the catacombs of Serapeum at Saqqara]] | ||

| + | After little success in acquiring manuscripts due to his inexperience, in order to avoid an embarrassing return empty-handed to [[France]] and wasting what might be his only trip to Egypt, Mariette visited temples and befriended a [[Bedouin]] friend, who led him to [[Saqqara]]. The site initially looked deserted, with nothing worthy of exploration. However, after noticing a [[sphinx]], he decided to explore the place, eventually leading to the discovery of the ruins of the [[Serapis|Serapeum]]—the [[cemetery]] of the sacred [[Apis]] [[bull]]s. | ||

| − | + | In 1851, he made his celebrated discovery, uncovering the Avenue of the Sphinxes and eventually the subterranean tomb-temple complex of [[catacomb]]s with their spectacular [[sarcophagus|sarcophagi]] of the Apis bulls. Breaking through the rubble at the tomb entrance on November 12, he entered the complex, finding thousands of [[statue]]s, [[bronze]] tablets, other treasures, and one intact sarcophagus. In the sarcophagus was the only remaining mummy, survived intact to the present day. | |

| − | Accused of theft and destruction by rival diggers and by the | + | [[Image:Louvres-antiquites-egyptiennes-p1020068.jpg|thumb|150 px|right| Statue of sacred Apis bull. Found at the Serapeum of Saqqara, in a chapel next to the processional way leading to the catacombs of the sacred bulls.]] |

| + | Accused of [[theft]] and destruction by rival diggers and by the [[Egypt]]ian authorities, Mariette had to rebury his finds in the [[desert]] to keep them from these competitors. He remained in Egypt for four years, excavating, discovering, and dispatching [[archaeology|archaeological]] treasures to the Louvre, as was the accepted system in his day. | ||

===Director of Antiquities=== | ===Director of Antiquities=== | ||

| − | + | Returning to [[France]], Mariette became dissatisfied with a purely academic role after his discoveries at [[Saqqara]]. Less than a year later he returned to [[Egypt]]. He was supported by the Egyptian government under [[Muhammad Ali Pasha the Great|Muhammad Ali]] and his successor [[Ismail Pasha]], who in 1858 created a position for him as the conservator of Egyptian monuments. | |

| − | Moving with his family to Cairo, | + | Moving with his family to [[Cairo]], Mariette’s career blossomed. Among other achievements, he was able to: |

| − | * | + | *gain government funds to set up the [[Egyptian Museum]] in [[Cairo]] (also known as the Bula Museum or Bulak Museum) in 1863 in order to take the pressure off the sites and stop the trade in illicit antiquities; |

| − | *the pyramid-fields of [[Memphis, Egypt|Memphis]] and | + | *explore the pyramid-fields of [[Memphis, Egypt|Memphis]] and, exploiting his previous success, find a cache of circa 2000 B.C.E.. painted wooden statues such as the [[Seated Scribe]], and the decorated tomb of [[Khafra]] and the tombs of [[Saqqara]]; |

| − | *the necropolis of [[Meidum]], and those of [[Abydos, Egypt|Abydos]] and [[Thebes, Egypt|Thebes]] | + | *explore the [[necropolis]] of [[Meidum]], and those of [[Abydos, Egypt|Abydos]] and [[Thebes, Egypt|Thebes]]; |

| − | *the great temples of [[Dendera]] and [[Edfu]] | + | *unearth the great temples of [[Dendera]] and [[Edfu]]; |

| − | * | + | *conduct excavations at [[Karnak]], [[Medinet Habu]], and [[Deir el-Bahri]], which marked the first full Egyptian use of the [[stratigraphy|stratigraphic]] methods developed by [[Karl Richard Lepsius]] |

| − | *[[ | + | *explore [[Tanis]], the Egyptian capital in the Late Period of [[ancient Egypt]] |

| − | * | + | *explore [[Jebel Barkal]] in [[Sudan]] |

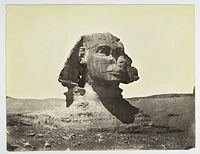

| − | * | + | *clear the sands around the [[Great Sphinx of Giza]] down to the bare rock, and in the process discovered the famous [[granite]] and [[alabaster]] monument, the "Temple of the Sphinx." |

| + | [[Image:GreatSphinx1867.jpg|thumb|left|200px|The Great Sphinx in 1867. Note its unrestored original condition with partially buried body.]] | ||

| + | In 1860, he set up 35 new dig sites, whilst attempting to conserve already-dug sites. His success was aided by the fact that no rivals were permitted to dig in Egypt, a fact that the [[Great Britain|British]] (who had previously had the majority of [[Egyptology|Egyptologists]] active in the country) and [[Germany|Germans]] (who were politically allied with the country's Ottoman rulers) protested at this "sweetheart deal" between Egypt and France. Nor were Mariette's relations with the [[Khedive]] always stable. The Khedive, like many potentates, assumed all discoveries ranked as treasure and that what went to the [[museum]] in Cairo went only at his pleasure. Even early on, in February 1859, Mariette dashed to Thebes to confiscate a large amount of antiquities from the nearby tomb of [[Queen Aotep]] that were to have been sent to the Khedive. | ||

| − | In | + | In 1867, he returned to France to oversee the ancient Egyptian stand at the World's Fair [[Exposition Universelle (1867)|Exposition Universelle]], held in [[Paris]]. He was welcomed as a hero for keeping France pre-eminent in Egyptology. |

| − | + | ===Later career=== | |

| + | In 1869, at the request of the [[Khedive]], Mariette wrote a brief plot for an [[opera]], which was later revised into the scenario by [[Camille du Locle]]. The plot was later developed by [[Giuseppe Verdi]], who adopted it as a subject for his opera ''[[Aida]].'' For this production, Mariette and du Locle oversaw the scenery and costumes, which were intended to be inspired by the art of [[ancient Egypt]]. ''Aida '' was to be premièred to mark the opening of the [[Suez Canal]], but was delayed until 1871. Intended for January of that year, the [[Cairo]] premiere was delayed again by the siege of [[Paris]] at the height of the [[Franco-Prussian War]]. It was finally performed in Cairo, on December 24, 1871. | ||

| − | Mariette was raised | + | Mariette was raised to the rank of [[pasha]], and European honors and orders were showered on him. |

| − | In 1878 | + | In 1878, the Cairo museum was ravaged by floods, destroying most of Mariette's notes and drawings. |

| − | + | Just before his death, prematurely aged and nearly blind, Mariette realized that he would not live much longer so he decided to appoint his own replacement in the Museum of Cairo. To ensure France retained supremacy in [[Egyptology]], he chose the Frenchman [[Gaston Maspero]], rather than an Englishman. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | Mariette died in Cairo in January 1881, and was interred in a [[sarcophagus]]. |

| − | + | ||

| + | ==Legacy== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mariette had never published as much as many noted scholars, and many of his notes and drawings were destroyed by flood. Nevertheless, he is remembered as one of the most renowned and well-known [[archaeology|archaeologists]]. He believed that [[Egypt]]ians should be able to keep their own antiquities, and founded the Museum of Cairo, which hosts one of the biggest collections of [[ancient Egypt]]ian artifacts in the world. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Publications== | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Mariette, Auguste. 1857. ''(Le) Sérapéum de Memphis''. Paris: Gide. | ||

| + | *Mariette, Auguste. 1875. ''Karnak: étude topographique et archéologique avec un appendice comprenant les principaux textes hiéroglyphiques découverts ou recueillis pendant les fouilles exécutées à Karnak''. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs. | ||

| + | *Mariette, Auguste. 1880. ''Catalogue général des monuments d'Abydos découverts pendant les fouilles de cette ville''. Paris: L'imprimerie nationale. | ||

| + | *Mariette, Auguste. [1888] 1976. ''Les mastabas de l'ancien empire: Fragment du dernier ouvrage de Auguste Édouard Mariette''. G. Olms. ISBN 3487059878 | ||

| + | *Mariette, Auguste. 1890. ''The monuments of Upper Egypt''. Boston: H. Mansfield & J.W. Dearborn. | ||

| + | *Mariette, Auguste. 1892. ''Outlines of Ancient Egyptian History''. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. | ||

| + | *Mariette, Auguste. 1981. ''Monuments divers recueillis en Egypte et en Nubie''. LTR-Verlag. ISBN 3887060636 | ||

| + | *Mariette, Auguste. 1999. ''Voyage dans la Haute-Egypte: Compris entre Le Caire et la première cataracte''. Errance. ISBN 2877721779 | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Brochet, Pierre, Béatrice Seguin, Elisabeth David, & Claudine Le Tourneur d'Ison. 2004. ''Mariette en Egypte, ou, La métamorphose des ruines''. Boulogne-sur-Mer: Bibliothèque municipale. | ||

| + | *Budden, Julian. 1981. ''The Operas of Verdi'',. vol. 3. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198162634 | ||

| + | *Lambert, Gilles. 1997. ''Auguste Mariette, l'Egypte ancienne sauvée des sables''. Paris: JC Lattès. ISBN 2709618222 | ||

| + | *Poiret, Françoise C. 1998. ''François Auguste Mariette: Champion de l'Egypte''. Boulogne-sur-Mer: Le Musée. | ||

| + | *Ridley, Ronald T. 1984. ''Auguste Mariette: One hundred years after''. Leiden: Brill. | ||

| + | *Ziegler, Christiane, and Marc Desti. 2004. ''Des dieux, des tombeaux, un savant: en Egypte, sur les pas de Mariette pacha''. Paris: Somogy. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | *[http://members.tripod.com/~ib205/ | + | All links retrieved August 21, 2023. |

| − | + | ||

| − | *[http://www.aldokkan.com/geography/serapeum.htm Mariette and the Serapeum at Saqqara | + | *[http://members.tripod.com/~ib205/apis_5.html Apis Bulls] – Account of Mariette's discovery of Apis bulls. |

| − | *[http:// | + | *[http://www.aldokkan.com/geography/serapeum.htm Serapeum] – Article on Mariette and the Serapeum at Saqqara. |

| + | *[http://members.tripod.com/~ib205/apis_4.html The Cemetery of the Sacred Bulls] – Excerpt from Mariette’s ''The Monuments of Upper Egypt''. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credit1|Auguste_Mariette|80794683|}} | {{Credit1|Auguste_Mariette|80794683|}} | ||

Latest revision as of 19:00, 21 August 2023

François Auguste Ferdinand Mariette (February 11, 1821 – January 19, 1881) was a French scholar and archaeologist, one of the early pioneers of Egyptology. He became famous for his discoveries at Saqqara, the vast, ancient burial ground in Memphis, capital of Ancient Egypt. There he uncovered the Avenue of the Sphinxes and the Serapeum, an ancient temple and cemetery of the sacred Apis bulls. Although originally sent to Egypt under the auspices of the French government, and thus obliged to send his findings to France for display in the Louvre, Mariette believed that the findings should remain in Egypt. He accepted a permanent position in Egypt and spent the rest of his life there, securing a monopoly on excavation. He founded of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, which became the foremost repository of Egyptian antiquities. Mariette's work was significant in opening the field of Egyptology, bringing knowledge of this dominant, somewhat mysterious, early civilization to the West, while at the same time advocating for the right of the Egyptian nation to retain ownership of its own historical artifacts.

Biography

Early career

François Auguste Ferdinand Mariette was born at Boulogne-sur-Mer, France, where his father was a town clerk. His first exposure to Egypt came in 1827, when he was only six years old. At the age of 12 he was already able to read ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and decipher Coptic writings. When his cousin Nestor L'Hote, the friend and fellow-traveler of Champollion died, the task of sorting his papers filled Mariette with a passion for Egyptology.

His 1847 analytic catalogue of the Egyptian Gallery of the Boulogne Museum led to a minor appointment at the Louvre Museum in 1849. He supplemented his salary as a teacher at Douai by giving private lessons and writing on historical and archaeological subjects for local periodicals.

Beginnings in Egypt

In 1849, the Louvre sent Mariette to Egypt to acquire Coptic, Ethiopic, and Syriac manuscripts to add to their collection. The acquisition of Egyptian artifacts by national and private collections was then a competitive endeavor, the English being able to pay higher prices. Mariette arrived in Egypt in 1850.

After little success in acquiring manuscripts due to his inexperience, in order to avoid an embarrassing return empty-handed to France and wasting what might be his only trip to Egypt, Mariette visited temples and befriended a Bedouin friend, who led him to Saqqara. The site initially looked deserted, with nothing worthy of exploration. However, after noticing a sphinx, he decided to explore the place, eventually leading to the discovery of the ruins of the Serapeum—the cemetery of the sacred Apis bulls.

In 1851, he made his celebrated discovery, uncovering the Avenue of the Sphinxes and eventually the subterranean tomb-temple complex of catacombs with their spectacular sarcophagi of the Apis bulls. Breaking through the rubble at the tomb entrance on November 12, he entered the complex, finding thousands of statues, bronze tablets, other treasures, and one intact sarcophagus. In the sarcophagus was the only remaining mummy, survived intact to the present day.

Accused of theft and destruction by rival diggers and by the Egyptian authorities, Mariette had to rebury his finds in the desert to keep them from these competitors. He remained in Egypt for four years, excavating, discovering, and dispatching archaeological treasures to the Louvre, as was the accepted system in his day.

Director of Antiquities

Returning to France, Mariette became dissatisfied with a purely academic role after his discoveries at Saqqara. Less than a year later he returned to Egypt. He was supported by the Egyptian government under Muhammad Ali and his successor Ismail Pasha, who in 1858 created a position for him as the conservator of Egyptian monuments.

Moving with his family to Cairo, Mariette’s career blossomed. Among other achievements, he was able to:

- gain government funds to set up the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (also known as the Bula Museum or Bulak Museum) in 1863 in order to take the pressure off the sites and stop the trade in illicit antiquities;

- explore the pyramid-fields of Memphis and, exploiting his previous success, find a cache of circa 2000 B.C.E. painted wooden statues such as the Seated Scribe, and the decorated tomb of Khafra and the tombs of Saqqara;

- explore the necropolis of Meidum, and those of Abydos and Thebes;

- unearth the great temples of Dendera and Edfu;

- conduct excavations at Karnak, Medinet Habu, and Deir el-Bahri, which marked the first full Egyptian use of the stratigraphic methods developed by Karl Richard Lepsius

- explore Tanis, the Egyptian capital in the Late Period of ancient Egypt

- explore Jebel Barkal in Sudan

- clear the sands around the Great Sphinx of Giza down to the bare rock, and in the process discovered the famous granite and alabaster monument, the "Temple of the Sphinx."

In 1860, he set up 35 new dig sites, whilst attempting to conserve already-dug sites. His success was aided by the fact that no rivals were permitted to dig in Egypt, a fact that the British (who had previously had the majority of Egyptologists active in the country) and Germans (who were politically allied with the country's Ottoman rulers) protested at this "sweetheart deal" between Egypt and France. Nor were Mariette's relations with the Khedive always stable. The Khedive, like many potentates, assumed all discoveries ranked as treasure and that what went to the museum in Cairo went only at his pleasure. Even early on, in February 1859, Mariette dashed to Thebes to confiscate a large amount of antiquities from the nearby tomb of Queen Aotep that were to have been sent to the Khedive.

In 1867, he returned to France to oversee the ancient Egyptian stand at the World's Fair Exposition Universelle, held in Paris. He was welcomed as a hero for keeping France pre-eminent in Egyptology.

Later career

In 1869, at the request of the Khedive, Mariette wrote a brief plot for an opera, which was later revised into the scenario by Camille du Locle. The plot was later developed by Giuseppe Verdi, who adopted it as a subject for his opera Aida. For this production, Mariette and du Locle oversaw the scenery and costumes, which were intended to be inspired by the art of ancient Egypt. Aida was to be premièred to mark the opening of the Suez Canal, but was delayed until 1871. Intended for January of that year, the Cairo premiere was delayed again by the siege of Paris at the height of the Franco-Prussian War. It was finally performed in Cairo, on December 24, 1871.

Mariette was raised to the rank of pasha, and European honors and orders were showered on him.

In 1878, the Cairo museum was ravaged by floods, destroying most of Mariette's notes and drawings.

Just before his death, prematurely aged and nearly blind, Mariette realized that he would not live much longer so he decided to appoint his own replacement in the Museum of Cairo. To ensure France retained supremacy in Egyptology, he chose the Frenchman Gaston Maspero, rather than an Englishman.

Mariette died in Cairo in January 1881, and was interred in a sarcophagus.

Legacy

Mariette had never published as much as many noted scholars, and many of his notes and drawings were destroyed by flood. Nevertheless, he is remembered as one of the most renowned and well-known archaeologists. He believed that Egyptians should be able to keep their own antiquities, and founded the Museum of Cairo, which hosts one of the biggest collections of ancient Egyptian artifacts in the world.

Publications

- Mariette, Auguste. 1857. (Le) Sérapéum de Memphis. Paris: Gide.

- Mariette, Auguste. 1875. Karnak: étude topographique et archéologique avec un appendice comprenant les principaux textes hiéroglyphiques découverts ou recueillis pendant les fouilles exécutées à Karnak. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs.

- Mariette, Auguste. 1880. Catalogue général des monuments d'Abydos découverts pendant les fouilles de cette ville. Paris: L'imprimerie nationale.

- Mariette, Auguste. [1888] 1976. Les mastabas de l'ancien empire: Fragment du dernier ouvrage de Auguste Édouard Mariette. G. Olms. ISBN 3487059878

- Mariette, Auguste. 1890. The monuments of Upper Egypt. Boston: H. Mansfield & J.W. Dearborn.

- Mariette, Auguste. 1892. Outlines of Ancient Egyptian History. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

- Mariette, Auguste. 1981. Monuments divers recueillis en Egypte et en Nubie. LTR-Verlag. ISBN 3887060636

- Mariette, Auguste. 1999. Voyage dans la Haute-Egypte: Compris entre Le Caire et la première cataracte. Errance. ISBN 2877721779

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brochet, Pierre, Béatrice Seguin, Elisabeth David, & Claudine Le Tourneur d'Ison. 2004. Mariette en Egypte, ou, La métamorphose des ruines. Boulogne-sur-Mer: Bibliothèque municipale.

- Budden, Julian. 1981. The Operas of Verdi,. vol. 3. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198162634

- Lambert, Gilles. 1997. Auguste Mariette, l'Egypte ancienne sauvée des sables. Paris: JC Lattès. ISBN 2709618222

- Poiret, Françoise C. 1998. François Auguste Mariette: Champion de l'Egypte. Boulogne-sur-Mer: Le Musée.

- Ridley, Ronald T. 1984. Auguste Mariette: One hundred years after. Leiden: Brill.

- Ziegler, Christiane, and Marc Desti. 2004. Des dieux, des tombeaux, un savant: en Egypte, sur les pas de Mariette pacha. Paris: Somogy.

External links

All links retrieved August 21, 2023.

- Apis Bulls – Account of Mariette's discovery of Apis bulls.

- Serapeum – Article on Mariette and the Serapeum at Saqqara.

- The Cemetery of the Sacred Bulls – Excerpt from Mariette’s The Monuments of Upper Egypt.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.