Anxiety disorder

| Anxiety disorder | |

| |

| The Scream (Norwegian: Skrik) a painting by Norwegian artist Edvard Munch | |

| Symptoms | Worrying, fast heart rate, shakiness[1] |

|---|---|

| Complications | Depression, insomnia, substance misuse, suicide[2] |

| Usual onset | 15–35 years old[3] |

| Duration | > 6 months[1][3] |

| Causes | Genetic, environmental, and psychological factors[4] |

| Risk factors | Child abuse, family history, poverty[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Psychological assessment |

| Differential diagnosis | Hyperthyroidism; heart disease; caffeine, alcohol, cannabis use; withdrawal from certain drugs[3] |

| Treatment | Lifestyle changes, counselling, medications[3] |

| Medication | Antidepressants, anxiolytics, beta blockers, Pregabalin[4] |

Anxiety disorders are a cluster of mental disorders characterized by severe and uncontrollable feelings of anxiety that significantly impact a person's social, occupational, and personal functioning. Anxiety may cause physical and cognitive symptoms, such as restlessness, irritability, difficulty concentrating, increased heart rate, abdominal pain, and a variety of other symptoms that vary based on the individual.

There are several types of anxiety disorders, the major ones being generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, Obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Also included within the anxiety disorders are specific phobias, fear of a particular situation or object. It is possible for an individual to have more than one anxiety disorder during their life or at the same time.

Anxiety disorders are common mental disorders. However, they are treatable and most people suffering from them are able to lead normal productive lives.

Definitions

Anxiety disorders are a cluster of mental disorders characterized by severe and uncontrollable feelings of anxiety and fear such that a person's social, occupational, and personal function are significantly impaired. The anxiety may cause physical and cognitive symptoms, such as restlessness, irritability, easy fatiguability, difficulty concentrating, increased heart rate, chest pain, abdominal pain, and a variety of other symptoms that may vary based on the individual.[1]

In casual discourse, the words anxiety and fear are often used interchangeably. In clinical usage, they have distinct meanings: anxiety is defined as an unpleasant emotional state for which the cause is either not readily identified or perceived to be uncontrollable or unavoidable, whereas fear is an emotional and physiological response to a recognized external threat.[5]

Anxiety is linked to fear and manifests as a future-oriented mood state that consists of a complex cognitive, affective, physiological, and behavioral response system associated with preparation for the anticipated events or circumstances perceived as threatening.[6]

Anxiety is an emotion which is characterized by an unpleasant state of inner turmoil and includes feelings of dread over anticipated events.[7][8] It is a feeling of uneasiness and worry, usually generalized and unfocused as an overreaction to a situation that is only subjectively seen as menacing.[9] Anxiety is often accompanied by nervous behavior such as pacing back and forth, somatic anxiety, and rumination,[10] People facing anxiety may withdraw from situations which have provoked anxiety in the past.[11]

Experiencing occasional anxiety is a normal part of life: "Anxiety is an adaptive response that promotes harm avoidance, but at the same time excessive anxiety constitutes the most common psychiatric complaint."[12] However, people with anxiety disorders frequently have intense, excessive, and persistent worry and fear about everyday situations. Anxiety disorders often involve repeated episodes of sudden feelings of intense anxiety and fear or terror, constituting panic attacks.[13]

Types

There are multiple forms of anxiety disorders, the main types being generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, Obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. The individual disorder can be diagnosed using the specific and unique symptoms, triggering events, and timing, and a person may experience more than one type during their life or even at the same time. To be diagnosed as having an anxiety disorder, a medical professional must have evaluated the person to ensure that their anxiety cannot be attributed to another medical illness or mental disorder.[1]

In addition to these disorders manifesting as severe chronic anxiety, there are also phobias, which manifest as strong, persistent, and irrational fear or anxiety related to certain situations, objects, activities, or persons.

Generalized anxiety disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a common disorder, characterized by long-lasting anxiety which is not focused on any one object or situation. It is "characterized by chronic excessive worry accompanied by three or more of the following symptoms: restlessness, fatigue, concentration problems, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance."[14] Those with generalized anxiety disorder experience non-specific persistent fear and worry, and become overly concerned with everyday matters.

A diagnosis of GAD is made when a person has been excessively worried about an everyday problem for six months or more.[11] These stresses can include family life, work, social life, or their own health. A person may find that they have problems making daily decisions and remembering commitments as a result of lack of concentration and/or preoccupation with worry. Before a diagnosis of anxiety disorder is made, physicians must rule out drug-induced anxiety and other medical causes.[15]

Generalized anxiety disorder is the most common anxiety disorder to affect older adults.[16] In children, GAD may be associated with headaches, restlessness, abdominal pain, and heart palpitations. Typically it begins around 8 to 9 years of age.[17]

Panic disorder

With panic disorder, a person has brief attacks of intense terror and apprehension, often marked by trembling, shaking, confusion, dizziness, nausea, and/or difficulty breathing. These panic attacks begin suddenly and usually peak quickly, within 10 minutes or less of starting.[1] Attacks can be triggered by stress, irrational thoughts, general fear or fear of the unknown, or even exercise. However, sometimes the trigger is unclear and the attacks can arise without warning. To help prevent an attack, one can avoid the trigger, namely places, people, types of behaviors, or certain situations that have been known to cause a panic attack. However, not all attacks can be prevented.

In addition to recurrent unexpected panic attacks, a diagnosis of panic disorder requires that said attacks have chronic consequences: either worry over the attacks' potential implications, persistent fear of future attacks, or significant changes in behavior related to the attacks. As such, those with panic disorder experience symptoms even outside specific panic episodes. Often, normal changes in heartbeat are noticed, leading them to think something is wrong with their heart or they are about to have another panic attack. In some cases, a heightened awareness (hypervigilance) of body functioning occurs during panic attacks, wherein any perceived physiological change is interpreted as a possible life-threatening illness (extreme hypochondriasis).

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), known as “shell shock” during the years of World War I and “combat fatigue” after World War II, results from having "experienced or witnessed a traumatic event such as a natural disaster, a serious accident, a terrorist act, war/combat, or rape or who have been threatened with death, sexual violence or serious injury."[18]

Common symptoms include hypervigilance, flashbacks, avoidant behaviors, anxiety, anger, and depression.[19] People who have PTSD often try to detach themselves from their friends and family, and have difficulty maintaining these close relationships.

There are a number of treatments that form the basis of the care plan for those with PTSD. Such treatments include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), prolonged exposure therapy, stress inoculation therapy, medication, and psychotherapy and support from family and friends.[11]

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) research began with Vietnam veterans, as well as natural and non-natural disaster victims. Studies have found the degree of exposure to a disaster has been found to be the best predictor of PTSD.[20]

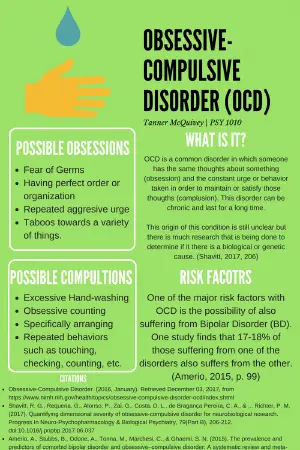

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a condition where the person has obsessions (distressing, persistent, and intrusive thoughts or images) and compulsions (urges to repeatedly perform specific acts or rituals), that are not caused by drugs or physical disorder, and which cause distress or social dysfunction.[21][22]

As indicated by the disorder's name, the primary symptoms of OCD are obsessions and compulsions. Obsessions are persistent unwanted thoughts, mental images, or urges that generate feelings of anxiety, disgust, or discomfort. An obsession is an unwanted and unpleasant thought, image or urge that repeatedly enters your mind, causing feelings of anxiety, disgust or unease. A compulsion is a repetitive behavior or mental act that you feel you need to do to temporarily relieve the unpleasant feelings brought on by the obsessive thought.[23]

Common obsessions include fear of contamination, obsession with symmetry, and intrusive thoughts about religion, sex, and harm. Compulsions are repeated actions or routines that occur in response to obsessions. Common compulsions include excessive hand washing, cleaning, counting, ordering, hoarding, neutralizing, seeking assurance, and checking things. Washing is in response to the fear of contamination. Ordering is the preference for tasks to be completed a specific way (such as organizing clothes a specific way). Hoarding is the collecting of unnecessary objects (like collecting food wrappers). Neutralizing is the act of engaging in a ritual to make up for supposedly "bad behavior." Checking is the compulsion to check particular objects/places to ensure they are a certain way (for example, checking to ensure the water is turned off). Many adults with OCD are aware that their compulsions do not make sense, but they perform them anyway to relieve the distress caused by obsessions.[24]

Compulsions occur so often, typically taking up at least one hour per day, that they impair one's quality of life. The compulsive rituals are personal rules followed to relieve the feeling of discomfort. A person with OCD knows that the symptoms are unreasonable and struggles against both the thoughts and the behavior.[21] OCD affects roughly 1–2 percent of adults (somewhat more women than men), and under 3 percent of children and adolescents.[21][22]

It is not certain why some people have OCD, but behavioral, cognitive, genetic, and neurobiological factors may be involved.[22] Of those with OCD, about 20 percent of people will overcome it, and symptoms will at least reduce over time for most people (a further 50 percent).[21]

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is classified as "Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders " in the American Psychiatric Association (APA)'s DSM-5, although it was previously classified as an anxiety disorder in the DSM-IV.[25] Similarly, it was classified as an anxiety disorder in the World Health Organization (WHO)'s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), but not in ICD-11.[26]

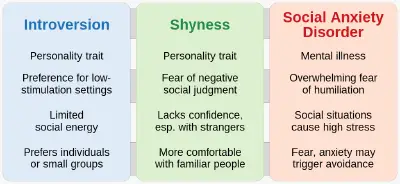

Social anxiety disorder

Social anxiety disorder (SAD; also known as social phobia) describes an intense fear and avoidance of negative public scrutiny, public embarrassment, humiliation, or social interaction. This fear can be specific to particular social situations (such as public speaking) or, more typically, is experienced in most (or all) social interactions. Roughly 7 percent of American adults suffer from social anxiety disorder, and more than 75 percent of them experience their first symptoms in their childhood or early teenage years.[27] Social anxiety often manifests specific physical symptoms, including blushing, sweating, rapid heart rate, and difficulty speaking.[28] As with all phobic disorders, those with social anxiety often will attempt to avoid the source of their anxiety; in the case of social anxiety this is particularly problematic, and in severe cases can lead to complete social isolation.

Children are also affected by social anxiety disorder, although their associated symptoms are different than that of teenagers and adults. They may experience difficulty processing or retrieving information, sleep deprivation, disruptive behaviors in class, and irregular class participation.[29]

Specific phobias

The specific phobias are a category of anxiety disorders which includes all cases in which fear and anxiety are triggered by a specific stimulus or situation. Between 5 and 12 percent of the population worldwide have specific phobias.[11] Individuals with a phobia typically anticipate terrifying consequences from encountering the object of their fear, which can be anything from an animal to a location to a bodily fluid to a particular situation. Common phobias are flying, blood, water, highway driving, and tunnels. When people are exposed to their phobia, they may experience trembling, shortness of breath, or rapid heartbeat.

People with specific phobias often go out of their way to avoid encountering their phobia. They understand that their fear is not proportional to the actual potential danger but still are overwhelmed by it.[30]

Diagnosis

Anxiety disorders differ from normal fear or anxiety by being excessive or persisting beyond developmentally appropriate periods. They differ from transient fear or anxiety, often stress-induced, by being persistent (typically lasting 6 months or more), although the criterion for duration is intended as a general guide with allowance for some degree of flexibility and is sometimes of shorter duration in children.[1]

The diagnosis of an anxiety disorder requires first ruling out an underlying medical cause; there are many diseases that include similar symptoms.[5] Several drugs can also cause or worsen anxiety, whether in intoxication, withdrawal, or from chronic use. These include alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, sedatives (including prescription benzodiazepines), opioids (including prescription painkillers and illicit drugs like heroin), stimulants (such as caffeine, cocaine, and amphetamines), hallucinogens, and inhalants.[3][1]

The diagnosis of anxiety disorders is made by symptoms, triggers, and a person's personal and family histories. There are no objective biomarkers or laboratory tests that can diagnose anxiety. Numerous questionnaires have been developed for clinical use and can be used for an objective scoring system. Symptoms may be vary between each subtype of generalized anxiety disorder. Generally, symptoms must be present for at least six months, occur more days than not, and significantly impair a person's ability to function in daily life. Symptoms may include: feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge; worrying excessively; difficulty concentrating; restlessness; irritability.[1][3]

Treatment

Treatment options include lifestyle changes, therapy, and medications. There is no clear evidence as to whether therapy or medication is most effective; the specific medication decision can be made by a doctor and patient with consideration to the patient's specific circumstances and symptoms.[31] Specific treatments will vary by subtype of anxiety disorder, a person's other medical conditions, and medications.

Lifestyle and diet

Lifestyle changes include exercise, for which there is moderate evidence for some improvement, regularizing sleep patterns, reducing caffeine intake, and stopping smoking.[31]

Psychotherapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been found to be effective for anxiety disorders and is a first-line treatment.[31]

Mindfulness-based programs also appear to be effective for managing anxiety disorders.[32]

Adventure-based counseling can be an effective way to anxiety. Using rock-climbing as an example, climbing can often bring on fear or frustration, and tackling these negative feelings in a nurturing environment can help people develop coping mechanisms necessary to deal with these negative feelings.

Medications

First-line choices for medications include SSRIs or SNRIs to treat generalized anxiety disorder.[31]

Buspirone and pregabalin are second-line treatments for people who do not respond to SSRIs or SNRIs; there is also evidence that benzodiazepines, including diazepam and clonazepam, are effective.[31]

Medications need to be used with care among older adults, who are more likely to have side effects because of coexisting physical disorders. Adherence problems are more likely among older people, who may have difficulty understanding, seeing, or remembering instructions.[16]

Epidemiology

Globally, anxiety disorders are one of the most common mental disorders, second only to substance abuse disorder in the United States. Data from 2010 show that in Europe, Africa, and Asia, lifetime rates of anxiety disorders are between 9 and 16 percent, and yearly rates are between 4 and 7 percent. In the United States, the lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders is higher, over 20 percent, and between 11 and 18 percent of adults have the condition in a given year.[33] The differences in rates affected by the range of ways in which different cultures interpret anxiety symptoms and what they consider to be normative behavior.[34] In general, anxiety disorders represent the most prevalent psychiatric condition in the United States, outside of substance use disorder.

Like adults, children can experience anxiety disorders; between 10 and 20 percent of all children will develop a full-fledged anxiety disorder prior to the age of 18, making anxiety the most common mental health issue in young people.[35] Anxiety disorders in children are often more challenging to identify than their adult counterparts, owing to the difficulty many parents face in discerning them from normal childhood fears. Likewise, anxiety in children is sometimes misdiagnosed as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or, due to the tendency of children to interpret their emotions physically (as stomachaches, headaches, and so forth), anxiety disorders may initially be confused with physical ailments.[36]

Anxiety in children has a variety of causes; sometimes anxiety is rooted in biology, and may be a product of another existing condition, such as autism spectrum disorder or ADHD. Other cases of anxiety arise from the child having experienced a traumatic event of some kind.[37]

Anxiety in children tends to manifest along age-appropriate themes, such as fear of going to school (not related to bullying) or not performing well enough at school, fear of social rejection, fear of something happening to loved ones, and so forth. What separates disordered anxiety from normal childhood anxiety is the duration and intensity of the fears involved.[37]

Stigma

People with an anxiety disorder may be challenged by prejudices and stereotypes that the world believes, most likely as a result of misconception around anxiety and anxiety disorders and mental illness in general.[38] Misconceptions found in a data analysis from the National Survey of Mental Health Literacy and Stigma include (1) many people believe anxiety is not a real medical illness; and (2) many people believe that people with anxiety could turn it off if they wanted to.[39]

For people experiencing the physical and mental symptoms of an anxiety disorder, stigma and negative social perception can make an individual less likely to seek treatment.[39]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013, ISBN 978-0890425558).

- ↑ Anxiety disorders – Symptoms and causes: Complications Mayo Clinic. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Michelle G. Craske and Murray B. Stein, Anxiety Lancet 388(10063) (2016): 3048–3059. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Anxiety Disorders National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 World Health Organization, Pharmacological Treatment of Mental Disorders in Primary Health Care (World Health Organization, 2010, ISBN 978-9241547697).

- ↑ Suma P. Chand and Raman Marwaha,Anxiety StatPearls Publishing, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Gerald C. Davison, Kirk R. Blankstein, Gordon L. Flett, and John M. Neale, Abnormal Psychology (Wiley, 2008, ISBN 978-0470840726).

- ↑ Maria Miceli and Cristiano Castelfranchi, Expectancy and Emotion (Oxford University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0199685868).

- ↑ Colin Hemmings and Nick Bouras (eds.), Psychiatric and Behavioral Disorders in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (Cambridge University Press, 2016, ISBN 978-1107645943).

- ↑ Martin E. P. Seligman, Elaine F. Walker, and David L. Rosenhan, Abnormal psychology (W. W. Norton & Company, 2001, ISBN 978-0393944594).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Mary Chambers (ed.), Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing: The craft of caring (Routledge, 2017, ISBN 1482221950).

- ↑ Oliver J. Robinson, Alexandra C. Pike, Brian Cornwell, and Christian Grillon, The translational neural circuitry of anxiety Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 90(12) (2019): 1353-1360. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Anxiety disorders Mayo Clinic Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ↑ Daniel L. Schacter, Daniel T. Gilbert, and Daniel M. Wegner, Psychology Second Edition (New York, NY: Worth Publishers, 2010, ISBN 978-1429237192).

- ↑ Elizabeth M. Varcarolis, Manual of Psychiatric Nursing Care Planning: Assessment Guides, Diagnoses and Psychopharmacology (Saunders, 2014, ISBN 978-1455740192).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Jessica Calleo and Melinda Stanley, Anxiety Disorders in Later Life: Differentiated Diagnosis and Treatment Strategies Psychiatric Times 26(8) (July, 2008). Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Courtney Pierce Keeton, Amie C. Kolos, and John T. Walkup, Pediatric generalized anxiety disorder: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management Paediatric Drugs 11(3) (2009):171–183. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ What Is What is Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)? American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Mayo Clinic. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Carol S. Fullerton and Robert J. Ursano (eds.), Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Acute and Long-Term Responses to Trauma and Disaster (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2009, ISBN 978-1585623808).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Core Interventions in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Body Dysmorphic Disorder (British Psychological Society and RCPsych Publications, 2006, ISBN 978-1854334305).

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 G. Mustafa Soomro, Obsessive compulsive disorder BMJ Clinical Evidence (January 18, 2012): 1004. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Symptoms of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) National Health Service (UK). Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder National institute of Mental Health. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ DSM-IV to DSM-5 Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Comparison National Library of Medicine, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Anna Marras, Naomi Fineberg, and Stefano Pallanti, Obsessive compulsive and related disorders: comparing DSM-5 and ICD-11 CNS Spectr 21(4) (2016):324-333. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Social Anxiety Disorder Mental Health America. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Social Anxiety Disorder: More Than Just Shyness National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Denise Egan Stack, Managing Anxiety in the Classroom Mental Health America, December 11, 2018. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Michael Passer and Ronald Smith, Psychology (McGraw-Hill Education, 2010, ISBN 978-0073532127).

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 Murray B. Stein and Jitender Sareen, Clinical Practice: Generalized Anxiety Disorder The New England Journal of Medicine 373(21) November 19, 2015):2059–2068. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Lizabeth Roemer, Sarah K. Williston, Elizabeth H. Eustis, and Susan M Orsillo, Mindfulness and acceptance-based behavioral therapies for anxiety disorders Curr Psychiatry Rep 15(11) (November 2013): 410. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Helen Blair Simpson, Yuval Neria, Roberto Lewis-Fernández, and Franklin Schneier (eds.), Anxiety Disorders: Theory, Research and Clinical Perspectives (Cambridge University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0521515573).

- ↑ Stefan G. Hofmann and Patricia M. DiBartolo (eds.), Social Anxiety: Clinical, Developmental, and Social Perspectives (Academic Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0123944276).

- ↑ Cecilia A. Essau (ed.), Child and Adolescent Psychopathology: Theoretical and Clinical Implications (Routledge, 2006, ISBN 978-1583918340).

- ↑ Anxiety Disorders in Children Anxiety Disorders Association of America (ADAA). Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Anxiety disorders in children National Health Service UK. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ↑ Patrick W. Corrigan, Lessons learned from unintended consequences about erasing the stigma of mental illness World Psychiatry 15(1) (2016): 67–73. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Stigma relating to anxiety Beyond Blue. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. ISBN 978-0890425558

- Chambers, Mary (ed.). Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing: The craft of caring. Routledge, 2017. ISBN 1482221950

- Davison, Gerald C., Kirk R. Blankstein, Gordon L. Flett, and John M. Neale. Abnormal Psychology. Wiley, 2008. ISBN 978-0470840726

- Essau, Cecilia A. (ed.). Child and Adolescent Psychopathology: Theoretical and Clinical Implications. Routledge, 2006. ISBN 978-1583918340

- Fullerton, Carol S., and Robert J. Ursano (eds.). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Acute and Long-Term Responses to Trauma and Disaster. American Psychiatric Publishing, 2009. ISBN 978-1585623808

- Hofmann, Stefan G., and Patricia M. DiBartolo (eds.). Social Anxiety: Clinical, Developmental, and Social Perspectives. Academic Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0123944276

- Miceli, Maria, and Cristiano Castelfranchi. Expectancy and Emotion. Oxford University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0199685868

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Core Interventions in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Body Dysmorphic Disorder. British Psychological Society and RCPsych Publications, 2006. ISBN 978-1854334305

- Passer,Michael, and Ronald Smith. Psychology. McGraw-Hill Education, 2010. ISBN 978-0073532127

- Schacter, Daniel L., Daniel T. Gilbert, and Daniel M. Wegner. Psychology Second Edition. New York, NY: Worth Publishers, 2010. ISBN 978-1429237192

- Seligman, Martin E. P., Elaine F. Walker, and David L. Rosenhan. Abnormal psychology. W. W. Norton & Company, 2001. ISBN 978-0393944594

- Simpson, Helen Blair, Yuval Neria, Roberto Lewis-Fernández, and Franklin Schneier (eds.). Anxiety Disorders: Theory, Research and Clinical Perspectives. Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0521515573

- Varcarolis, Elizabeth M. Manual of Psychiatric Nursing Care Planning: Assessment Guides, Diagnoses and Psychopharmacology. Saunders, 2014. ISBN 978-1455740192

- World Health Organization. Pharmacological Treatment of Mental Disorders in Primary Health Care. World Health Organization, 2010. ISBN 978-9241547697

External links

All links retrieved November 18, 2022.

- Anxiety disorders Mayo Clinic

- Anxiety Disorders National Institute of Mental Health

- Anxiety Disorders Cleveland Clinic

- What are Anxiety Disorders? American Psychiatric Association

- What are the five major types of anxiety disorders? U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Anxiety Disorders WebMD.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.