Difference between revisions of "Alphabet" - New World Encyclopedia

m (Copied from wikipedia) |

(Started) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Claimed}} | + | {{Claimed}}{{Started}} |

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Linguistics]] | [[Category:Linguistics]] | ||

| + | {{WStypes}} | ||

[[Image:Caslon-schriftmusterblatt.jpeg|thumb|right|320px|''A Specimen'' of typeset fonts and languages, by [[William Caslon]], letter founder; from the 1728 ''[[Cyclopaedia]]''.]] | [[Image:Caslon-schriftmusterblatt.jpeg|thumb|right|320px|''A Specimen'' of typeset fonts and languages, by [[William Caslon]], letter founder; from the 1728 ''[[Cyclopaedia]]''.]] | ||

| − | An '''alphabet''' is a | + | An '''alphabet''' is a standardized set of ''[[letter (alphabet)|letters]]'' — basic written symbols — each of which roughly represents a [[phoneme]] of a [[spoken language]], either as it exists now or as it was in the past. There are other [[writing system|systems of writing]] such as [[logograph]]ies, in which each character represents a word, and [[syllabary|syllabaries]], in which each character represents a [[syllable]], but alphabets are the most widespread writing system. Alphabets are in turn classified according to how they indicate vowels: as equal to consonants, as in [[Greek alphabet|Greek]], as modifications of consonants, as in [[Devanagari|Hindi]], or not at all, as in [[Arabic alphabet|Arabic]]. |

| − | The | + | The word "alphabet" came into [[Middle English]] from the [[Late Latin]] '''Alphabetum''', which in turn originated in the [[Ancient Greek]] '''Alphabetos''', from ''[[alpha (letter)|alpha]]'' and ''[[beta (letter)|beta]],'' the first two letters of the [[Greek alphabet]].<ref>[http://www.britannica.com/dictionary?book=Dictionary&va=alphabet&query=alphabet/ Encyclopædia Britannica Online - Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary]</ref> There are dozens of alphabets in use today. Most of them are composed of lines ([[linear writing]]); notable [[non-linear writing|exceptions]] are [[Braille]], [[fingerspelling]], and [[Morse code]]. |

==Linguistic definition and context== | ==Linguistic definition and context== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | A [[grapheme]] is an abstract entity which may be physically represented by different styles of [[glyph]]s. There are many written entities which do not form part of the alphabet, including [[numeral]]s, [[mathematical symbol]]s, and [[punctuation]]. Some human languages are commonly written by using a combination of [[logograms]] (which represent [[morphemes]] or [[word]]s) and [[ | + | {{main|Writing system}} |

| + | The term '''alphabet''' prototypically refers to a writing system that has characters ([[grapheme]]s) for representing both consonant and vowel sounds, even though there may not be a complete one-to-one correspondence between symbol and sound. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A [[grapheme]] is an abstract entity which may be physically represented by different styles of [[glyph]]s. There are many written entities which do not form part of the alphabet, including [[numeral]]s, [[mathematical symbol]]s, and [[punctuation]]. Some human languages are commonly written by using a combination of [[logograms]] (which represent [[morphemes]] or [[word]]s) and [[syllabaries]] (which represent [[syllables]]) instead of an alphabet. [[Egyptian hieroglyph]]s and [[Chinese character]]s are two of the best-known writing systems with predominantly non-alphabetic representations. | ||

Non-written languages may also be represented alphabetically. For example, linguists researching a non-written language (such as some of the indigenous Amerindian languages) will use the International Phonetic Alphabet to enable them to write down the sounds they hear. | Non-written languages may also be represented alphabetically. For example, linguists researching a non-written language (such as some of the indigenous Amerindian languages) will use the International Phonetic Alphabet to enable them to write down the sounds they hear. | ||

| Line 21: | Line 23: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{alphabet}} |

| − | {{ | + | The '''history of the [[alphabet]]''' begins in [[Ancient Egypt]], more than a millennium into the [[history of writing]]. The first pure alphabet emerged around 2000 B.C.E. to represent the language of [[Semitic]] workers in Egypt (see [[Middle Bronze Age alphabets]]), and was derived from the alphabetic principles of the [[Egyptian hieroglyph]]s. Most alphabets in the world today either descend directly from this development, for example the [[Greek alphabet|Greek]] and [[Latin alphabet|Latin]] alphabets, or were inspired by its design. <ref>Himelfarb, Elizabeth J. "First Alphabet Found in Egypt," ''Archaeology'' 53, Issue 1 (Jan./Feb. 2000): 21.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | ===Pre-alphabetic scripts=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Two scripts are well attested from before the end of the fourth millennium B.C.E.: [[cuneiform script|Mesopotamian cuneiform]] and [[Egyptian hieroglyphs]]. Both were well known in the part of the Middle East that produced the first widely used alphabet, the [[Phoenician alphabet|Phoenician]]. There are signs that cuneiform was developing alphabetic properties in some of the languages it was adapted for, as was seen again later in the [[Old Persian cuneiform script]], but it now appears these developments were a sideline and not ancestral to the alphabet. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====The Beginnings in Egypt==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | By 2700 B.C.E. the [[ancient Egyptians]] had developed a set of some [[Egyptian hieroglyph#Uniliteral signs|22 hieroglyphs]] to represent the individual [[consonant]]s of their language, plus a 23<sup>rd</sup> that seems to have represented word-initial or word-final [[vowel]]s. These glyphs were used as pronunciation guides for [[logogram]]s, to write grammatical inflections, and, later, to transcribe loan words and foreign names. However, although alphabetic in nature, the system was not used for purely alphabetic writing. That is, while capable of being used as an alphabet, it was in fact always used with a strong logographic component, presumably due to strong cultural attachment to the complex Egyptian script. The first purely alphabetic script is thought to have been developed around 2000 B.C.E. for [[Semitic]] workers in central Egypt. Over the next five centuries it spread north, and all subsequent alphabets around the world have either descended from it, or been inspired by one of its descendants, with the possible exception of the [[Meroitic script|Meroitic alphabet]], a 3rd century B.C.E. adaptation of hieroglyphs in [[Nubia]] to the south of Egypt - though even here many scholars suspect the influence of that first alphabet.{{Fact|date=May 2007}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====The Semitic alphabet==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Middle Bronze Age alphabets|Middle Bronze Age scripts]] of Egypt have yet to be deciphered. However, they appear to be at least partially, and perhaps completely, alphabetic. The oldest examples are found as [[Graffito (archaeology)|graffiti]] from central Egypt and date to around 1800 B.C.E. [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/521235.stm]/[http://www.trussel.com/prehist/news170.htm]. <ref>Himelfarb, Elizabeth J. "First Alphabet Found in Egypt," ''Archaeology'' 53, Issue 1 (Jan./Feb. 2000): 21.</ref> These inscriptions, according to Gordon J. Hamilton, help to show that the most likely place for the alphabet’s invention was in Egypt proper. <ref>Hamilton, Gordon J. "W. F. Albright and Early Alphabetic Writing," ''Near Eastern Archaeology'' 65, No. 1 (Mar., 2002): 35-42. page 39-49.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This Semitic script did not restrict itself to the existing Egyptian consonantal signs, but incorporated a number of other Egyptian hieroglyphs, for a total of perhaps thirty, and used Semitic names for them.<ref>Hooker, J. T., C. B. F. Walker, W. V. Davies, John Chadwick, John F. Healey, B. F. Cook, and Larissa Bonfante, (1990). ''Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet''. Berkeley: University of California Press. pages 211-213.</ref> So, for example, the hieroglyph ''[[Per (hieroglyph)|per]]'' ("house" in Egyptian) became ''bayt'' ("house" in Semitic).<ref>McCarter, P. Kyle. “The Early Diffusion of the Alphabet.” ''The Biblical Archaeologist'' 37, No. 3 (Sep., 1974): 54-68. page 57.</ref> It is unclear at this point whether these glyphs, when used to write the Semitic language, were purely alphabetic in nature, representing only the first consonant of their names according to the [[acrophony|acrophonic principle]], or whether they could also represent sequences of consonants or even words as their hieroglyphic ancestors had. For example, the "house" glyph may have stood only for ''b'' (''b'' as in ''beyt'' "house"), or it may have stood for both the consonant ''b'' and the sequence ''byt'', as it had stood for both ''p'' and the sequence ''pr'' in Egyptian. However, by the time the script was inherited by the [[Canaan]]ites, it was purely alphabetic, and the hieroglyph originally representing "house" stood only for ''b''.<ref>Hooker, J. T., C. B. F. Walker, W. V. Davies, John Chadwick, John F. Healey, B. F. Cook, and Larissa Bonfante, (1990). ''Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet'', Berkeley: University of California Press. page 212.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first Canaanite state to make extensive use of the alphabet was [[Phoenicia]], and so later stages of the Canaanite script are called [[Phoenician alphabet|Phoenician]]. Phoenicia was a maritime state at the center of a vast trade network, and soon the Phoenician alphabet spread throughout the Mediterranean. [http://phoenicia.org/alphabet.html] Two variants of the Phoenician alphabet would have major impacts on the history of writing: the [[Aramaic alphabet]] and the [[Greek alphabet]]. [http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A2451890] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Descendants of the Aramaic abjad==== | ||

| + | |||

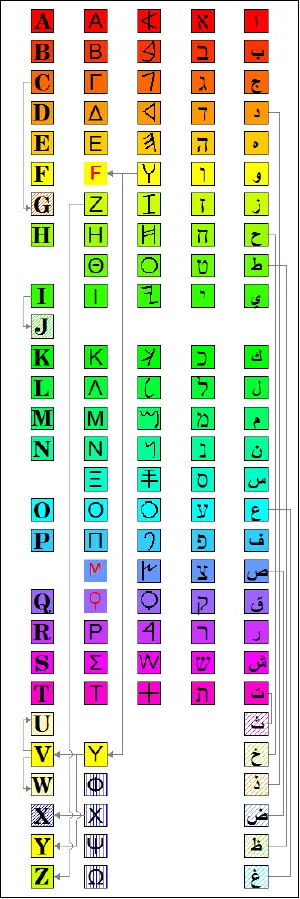

| + | [[Image:Phönizisch-5Sprachen.png|thumb|right|Chart showing details of four alphabets' descent from Phoenician abjad, from left to right [[Latin alphabet|Latin]], [[Greek alphabet|Greek]], original Phoenician, [[Hebrew alphabet|Hebrew]], [[Arabic alphabet|Arabic]].]] | ||

| + | |||

| − | The | + | The Phoenician and Aramaic alphabets, like their Egyptian prototype, represented only consonants, a system called an ''[[abjad]]''. The Aramaic alphabet, which evolved from the Phoenician in the 7th century B.C.E. as the official script of the [[Persian Empire]], appears to be the ancestor of nearly all the modern alphabets of Asia:{{Fact|date=May 2007}} |

| + | *The modern [[Hebrew alphabet]] started out as a local variant of Imperial Aramaic. (The original Hebrew alphabet has been retained by the [[Samaritan alphabet|Samaritans]].) <ref>Hooker, J. T., C. B. F. Walker, W. V. Davies, John Chadwick, John F. Healey, B. F. Cook, and Larissa Bonfante, (1990). ''Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet'', Berkeley: University of California Press. page 222.</ref> <ref>Robinson, Andrew, (1995). ''The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs & Pictograms'', New York: Thames & Hudson Ltd. page 172.</ref> | ||

| + | *The [[Arabic alphabet]] descended from Aramaic via the [[Nabatean]] alphabet of what is now southern [[Jordan]]. | ||

| + | *The [[Syriac alphabet]] used after the 3rd century CE evolved, through [[Pahlavi]] and [[Sogdian alphabet|Sogdian]], into the alphabets of northern Asia, such as [[Orkhon script|Orkhon]] (probably), [[Uyghur alphabet|Uyghur]], [[Mongolian alphabet|Mongolian]], and [[Manchu alphabet|Manchu]]. | ||

| + | *The [[Georgian alphabet]] is of uncertain provenance, but appears to be part of the Persian-Aramaic (or perhaps the Greek) family. | ||

| + | *The Aramaic alphabet is also the most likely ancestor of the [[Brahmic family|Brahmic alphabets]] of the [[Indian subcontinent]], which spread to [[Tibet]], [[Mongolia]], [[Indochina]], and the [[Malay archipelago]] along with the [[Hinduism|Hindu]] and [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] religions. ([[China]] and [[Japan]], while absorbing Buddhism, were already literate and retained their [[logogram|logographic]] and [[syllabary|syllabic]] scripts.) | ||

| + | *The [[Hangul]] alphabet was invented in [[Korea]] in the 15th century. Tradition holds that it was an autonomous invention; however, [[Gari Ledyard]] suggests that portions of its consonantal system may be based on half a dozen letters derived from [[Tibetan script|Tibetan]] via the imperial [[Phagspa script|Phagspa alphabet]] of the [[Yuan dynasty]] of China; Tibetan is a Brahmic script. Uniquely among the world's alphabets, the rest of the consonants are derived from this core as a [[Distinctive feature|featural]] system.{{Fact|date=May 2007}} | ||

| − | + | ===Transmission of the Alphabet to Greece=== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The Phoenician alphabet was the | + | By at least the 8th century B.C.E. the Greeks borrowed the Phoenician alphabet and adapted it to their own language.<ref>McCarter, P. Kyle. "The Early Diffusion of the Alphabet," ''The Biblical Archaeologist'' 37, No. 3 (Sep., 1974): 54-68. page 62.</ref> The letters of the Greek alphabet are the same as those of the Phoenician alphabet, and both alphabets are arranged in the same order. <ref>McCarter, P. Kyle. "The Early Diffusion of the Alphabet," ''The Biblical Archaeologist'' 37, No. 3 (Sep., 1974): 54-68. page 62.</ref> However, whereas separate letters for vowels would have actually hindered the legibility of Egyptian, Phoenician, or Hebrew, their absence was problematic for Greek, where [[vowel]]s played a much more important role. The Greeks adapted those Phoenician letters for consonants they couldn't pronounce to write vowels. All of the names of the letters of the Phoenician alphabet started with consonants, and these consonants were what the letters represented, something called the [[acrophony|acrophonic principle]]. However, several Phoenician consonants were rather soft and unpronounceable by the Greeks, and thus several letter names came to be pronounced with initial vowels. Since the start of the name of a letter was expected to be the sound of the letter, in Greek these letters now stood for vowels.{{Fact|date=May 2007}} For example, the Greeks had no glottal stop or ''h'', so the Phoenician letters ''’alep'' and ''he'' became Greek ''[[alpha (letter)|alpha]]'' and ''e'' (later renamed ''[[epsilon (letter)|e psilon]]''), and stood for the vowels {{IPA|/a/}} and {{IPA|/e/}} rather than the consonants {{IPA|/ʔ/}} and {{IPA|/h/}}. As this fortunate development only provided for five or six (depending on dialect) of the twelve Greek vowels, the Greeks eventually created [[digraph (orthography)|digraph]]s and other modifications, such as ''ei'', ''ou'', and <u>''o''</u> (which became [[omega (letter)|omega]]), or in some cases simply ignored the deficiency, as in long ''a, i, u''. <ref>Robinson, Andrew, (1995). ''The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs & Pictograms'', New York: Thames & Hudson Ltd. page 170.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | Several varieties of the Greek alphabet developed. One, known as [[Cumae alphabet|Western Greek or Chalcidian]], was west of [[Athens]] and in southern [[Italy]]. The other variation, known as [[History of the Greek alphabet|Eastern Greek]], was used in present-day [[Turkey]], and the Athenians, and eventually the rest of the world that spoke Greek, adopted this variation. After first writing right to left, the Greeks eventually chose to write from left to right, unlike the Phoenicians who wrote from right to left. [http://phoenicia.org/alphabet.html] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Descendants of the Greek Alphabet=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Greek is in turn the source for all the modern scripts of Europe. The alphabet of the early western Greek dialects, where the letter [[eta (letter)|eta]] remained an ''h'', gave rise to the [[Old Italic alphabet|Old Italic]] and [[Roman alphabet]]s. In the eastern Greek dialects, which did not have an /h/, eta stood for a vowel, and remains a vowel in modern Greek and all other alphabets derived from the eastern variants: [[Glagolitic alphabet|Glagolitic]], [[Cyrillic alphabet|Cyrillic]], [[Armenian alphabet|Armenian]], [[Gothic alphabet|Gothic]] (which used both Greek and Roman letters), and perhaps [[Georgian alphabet|Georgian]].<ref>Robinson, Andrew. The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs & Pictograms. New York: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 1995.</ref> <ref>BBC. "The Development of the Western Alphabet." [updated 8 April 2004; cited 1 May 2007]. Available from http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A2451890.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although this description presents the evolution of scripts in a linear fashion, this is a simplification. For example, the Manchu alphabet, descended from the abjads of West Asia, was also influenced by Korean hangul, which was either independent (the traditional view) or derived from the abugidas of South Asia. Georgian apparently derives from the Aramaic family, but was strongly influenced in its conception by Greek. The Greek alphabet, itself ultimately a derivative of hieroglyphs through that first Semitic alphabet, later adopted an additional half dozen [[demotic]] hieroglyphs when it was used to write [[Coptic alphabet|Coptic]] Egyptian. Then there is [[Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics|Cree Syllabics]] (an [[abugida]]), which appears to be a fusion of [[Devanagari]] and [[Pitman shorthand]]; the latter may be an independent invention, but likely has its ultimate origins in cursive Latin script. {{Fact|date=May 2007}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Development of the Roman Alphabet=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | A tribe known as the [[Latins]], who became known as the Romans, also lived in the Italian peninsula like the Western Greeks. From the [[Etruscan civilization|Etruscans]], a tribe living in the [[1st millennium B.C.E.|first millennium B.C.E.]] in central [[Italy]], and the Western Greeks, the Latins adopted writing in about the fifth century. In adopted writing from these two groups, the Latins dropped four characters from the Western Greek alphabet. They also adapted the Etruscan letter [[F]], pronounced 'w,' giving it the 'f' sound, and the Etruscan S, which had three zigzag lines, was curved to make the modern [[S]]. To represent the [[G]] sound in Greek and the [[K]] sound in Etruscan, the [[Gamma]] was used. These changes produced the modern alphabet without the letters G, [[J]], [[U]], [[W]], [[Y]], and [[Z]], as well as some other differences. [http://phoenicia.org/alphabet.html] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[C]], [[K]], and [[Q]] in the Romans’ alphabet could all be used to write the k sound, and C could also be used to write the sound 'g.' The Romans invented the letter G and inserted it into the alphabet between [[F]] and [[H]] for an unknown reason. Over the few centuries after [[Alexander the Great]] conquered the Eastern Mediterranean and other areas in the [[3rd century B.C.E.|third century B.C.E.]], the Romans began to borrow Greek words, so they had to adapt their alphabet again in order to write these words. From the Eastern Greek alphabet, they borrowed [[Y]] and [[Z]], which were added to the end of the alphabet because the only time they were used was to write Greek words. [http://phoenicia.org/alphabet.html] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Old English|Anglo-Saxon language]] began to be written using Roman letters after [[Britain in the Middle Ages|Britain]] was invaded by the [[Normans]] in the eleventh century. Because the [[Runic alphabet|Runic]] ''wen'', which was first used to represent the sound 'w' and looked like a p that is narrow and triangular, was easy to confuse with an actual p, the 'w' sound began to be written using a double u. Because the u at the time looked like a v, the double u looked like two v's, [[W]] was placed in the alphabet by [[V]]. [[U]] developed when people began to use the rounded U when they meant the vowel u and the pointed V when the meant the consonant V. [[J]] began as a variation of [[I]], in which a long tail was added to the final I when there were several in a row. People began to use the J for the consonant and the I for the vowel by the fifteenth century, and it was fully accepted in the mid-seventeenth century. [http://phoenicia.org/alphabet.html] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Letter Names and Sequence of Some Alphabets=== | ||

| + | The order of the letters of the alphabet is attested from the fourteenth century B.C.E., in a place called [[Ugarit]] located on [[Syria]]’s northern coast. <ref>Robinson, Andrew, (1995). ''The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs & Pictograms'', New York: Thames & Hudson Ltd. page 162.</ref> Tablets found there bear over one thousand cuneiform signs, but these signs are not Babylonian, and there are only thirty distinct characters. About twelve of the tablets have the signs set out in alphabetic order. There are two orders found, one which is nearly identical to the order used for [[Hebrew alphabet|Hebrew]], [[Greek alphabet|Greek]], and [[Latin alphabet|Latin]], and a second order very similar to that used for [[Ge'ez alphabet|Ethiopian]]. <ref>Millard, A.R. "The Infancy of the Alphabet," ''World Archaeology'' 17, No. 3, Early Writing Systems (Feb., 1986): 390-398. page 395.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is not known how many letters the [[Proto-Sinaitic alphabet]] had, nor what their alphabetic order was. Among its descendants, the [[Ugaritic alphabet]] had 27 consonants, the [[South Arabian alphabet]]s had 29, and the [[Phoenician alphabet]] was reduced to 22. These scripts were arranged in two orders, an ''ABGDE'' order in Phoenician, and an ''HMĦLQ'' order in the south; Ugaritic preserved both orders. Both sequences proved remarkably stable among the descendants of these scripts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The letter names proved stable among many descendants of Phoenician, including [[Samaritan alphabet|Samaritan]], [[Aramaic alphabet|Aramaic]], [[Syriac alphabet|Syriac]], [[Hebrew alphabet|Hebrew]], and [[Greek alphabet]]. However, they were abandoned in [[Arabic alphabet|Arabic]] and [[Latin alphabet|Latin]]. The letter sequence continued more or less intact into Latin, [[Armenian alphabet|Armenian]], [[Gothic alphabet|Gothic]], and [[Cyrillic alphabet|Cyrillic]], but was abandoned in [[Brahmi]], [[Runic alphabet|Runic]], and Arabic, although a traditional ''[[abjadi order]]'' remains or was re-introduced as an alternative in the latter. {{Fact|date=May 2007}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | These 22 consonants account for the phonology of [[Northwest Semitic]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Graphically independent alphabets=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The only modern national alphabet that has not been graphically traced back to the Canaanite alphabet is the [[Thaana|Maldivian]] script, which is unique in that, although it is clearly modeled after [[Arabic]] and perhaps other existing alphabets, it derives its letter forms from numerals. The [[Osmanya script|Osmanya alphabet]] devised for [[Somali language|Somali]] in the 1920s was co-official in Somalia with the Latin alphabet until 1972, and the forms of its consonants appear to be complete innovations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Among alphabets that are not used as national scripts today, a few are clearly independent in their letter forms. The [[Zhuyin]] phonetic alphabet derives from [[Chinese character]]s. The [[Santali alphabet]] of eastern India appears to be based on traditional symbols such as "danger" and "meeting place," as well as pictographs invented by its creator. (The names of the Santali letters are related to the sound they represent through the acrophonic principle, as in the original alphabet, but it is the ''final'' consonant or vowel of the name that the letter represents: ''le'' "swelling" represents ''e'', while ''en'' "thresh grain" represents ''n''.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the ancient world, [[Ogham]] consisted of tally marks, and the monumental inscriptions of the [[Old Persian]] Empire were written in an essentially alphabetic cuneiform script whose letter forms seem to have been created for the occasion. However, while all of these systems may have been ''graphically'' independent of the other alphabets of the world, they were devised from their example. {{Fact|date=May 2007}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Alphabets in other media=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Changes to a new writing medium sometimes caused a break in graphical form, or make the relationship difficult to trace. It is not immediately obvious that the cuneiform [[Ugaritic alphabet]] derives from a prototypical Semitic abjad, for example, although this appears to be the case. And while [[manual alphabet]]s are a direct continuation of the local written alphabet (both the [[Two-handed manual alphabet|British two-handed]] and the [[French Sign Language|French]]/[[American Sign Language alphabet|American one-handed]] alphabets retain the forms of the Latin alphabet, as the [[Indian Sign Language|Indian manual alphabet]] does [[Devanagari]], and the [[Korean manual alphabet|Korean]] does Hangul), [[Braille]], [[semaphore (communication)|semaphore]], [[International maritime signal flags|maritime signal flags]], and the [[Morse code]]s are essentially arbitrary geometric forms. The shapes of the English Braille and semaphore letters, for example, are derived from the [[alphabetic order]] of the Latin alphabet, but not from the graphic forms of the letters themselves. Modern [[shorthand]] also appears to be graphically unrelated. If it derives from the Latin alphabet, the connection has been lost to history. {{Fact|date=May 2007}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===Middle Eastern Scripts=== | ||

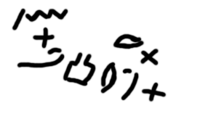

| + | [[Image:Ba`alat.png|thumb|left|200px|A specimen of Proto-Sinaitic script, one of the earliest (if not the very first) phonemic scripts]] | ||

| + | The history of the alphabet starts in [[ancient Egypt]]. By [[2700 B.C.E.|2700 <small>BCE</small>]] Egyptian writing had a set of some [[Egyptian uniliteral signs|22 hieroglyphs]] to represent syllables that begin with a single [[consonant]] of their language, plus a vowel (or no vowel) to be supplied by the native speaker. These glyphs were used as pronunciation guides for [[logogram]]s, to write grammatical inflections, and, later, to transcribe loan words and foreign names.<ref>Daniels and Bright (1996), pp. 74-75.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, although seemingly alphabetic in nature, the original Egyptian uniliterals were not a system and were never used by themselves to encode Egyptian speech.<ref>Daniels and Bright (1996), pp. 74.</ref> In the [[Middle Bronze Age]] an apparently "alphabetic" system known as the [[Middle Bronze Age alphabets#The Proto-Sinaitic script|Proto-Sinaitic script]] is thought by some to have been developed in central [[Egypt]] around 1700 B.C.E. for or by [[Semitic]] workers, but only one of these early writings has been deciphered and their exact nature remains open to interpretation.<ref name="Coulmas 140">Coulmas (1989), p. 140.</ref> Based on letter appearances and names, it is believed to be based on Egyptian hieroglyphs.<ref name="Coulmas 140" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This script eventually developed into the [[Proto-Canaanite alphabet]], which in turn was refined into the [[Phoenician alphabet]].<ref>Daniels and Bright (1996), pp. 92-94.</ref> Note that the scripts mentioned above are not considered proper alphabets, as they all lack characters representing vowels. These early vowelless alphabets are called [[abjad]]s, and still exist in scripts such as the [[Arabic alphabet|Arabic]] and [[Hebrew alphabet|Hebrew]] scripts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Phoenician was the first major phonemic script.<ref name="Daniels 9496">Daniels and Bright (1996), pp. 94-96.</ref><ref>Coulmas (1989), p. 141.</ref> In contrast to two other widely used writing systems at the time, [[Cuneiform]] and [[Egyptian hieroglyphs]], each of which contained thousands of different characters, it contained only about two dozen distinct letters, making it a script simple enough for common traders to learn. Another advantage to Phoenician was that it could be used to write down many different languages, since it recorded words phonemically. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The script was spread by the Phoenicians, whose [[Thalassocracy]] allowed the script to be spread across the Mediterranean.<ref name="Daniels 9496" /> In Greece, the script was modified to add the vowels, giving rise to the first true alphabet. The Greeks took letters which did not represent sounds that existed in Greek, and changed them to represent the vowels. This marks the creation of a "true" alphabet, with the presence of both vowels and consonants as explicit symbols in a single script. In its early years, there were many variants of the Greek alphabet, a situation which caused so many different alphabets to evolve from it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===European alphabets=== | ||

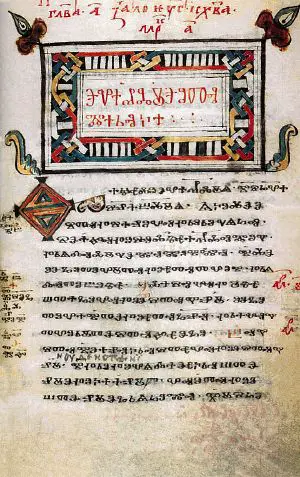

| + | [[Image:ZographensisColour.jpg|thumb|[[Codex Zographensis]] in the Glagolitic alphabet from Medieval [[Bulgaria]].]] | ||

| + | The [[Cumae alphabet|Cumae form]] was carried over to the Italian peninsula, where it gave way to a variety of alphabets used to inscribe the [[Italic languages]]. One of these became the [[Latin alphabet]], which was spread across Europe as the Romans expanded their empire. Even after the fall of the Roman state, the alphabet survived in intellectual and religious works. It eventually became used for the descendant languages of Latin (the [[Romance languages]]), and then for the other languages of Europe. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Another notable script is [[Elder Futhark]], and is believed to have evolved out of one of the [[Old Italic alphabet]]s. Elder Futhark gave rise to a variety of alphabets known collectively as the [[Runic alphabet]]s. The Runic alphabets were used for Germanic languages from 100 C.E. to the late Middle Ages. Its usage was mostly restricted to engravings on stone and jewelry, although inscriptions have also been found on bone and wood. These alphabets have since been replaced with the Latin alphabet, except for decorative usage for which the runes remained in use until the 20th century. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Glagolitic alphabet]] was the script of the liturgical language [[Old Church Slavonic]], and became the basis of the [[Cyrillic alphabet]]. The Cyrillic alphabet is one of the most widely used modern alphabets, and is notable for its use in Slavic languages and languages formerly part of the Soviet Union, such as the [[Bulgarian alphabet|Bulgarian]] and [[Russian alphabet]]s. The Glagolitic alphabet is believed to have been created by [[Saints Cyril and Methodius]], while the Cyrillic alphabet was invented by the [[Bulgarians|Bulgarian]] scholar [[Clement of Ohrid]], who was their disciple. They feature many letters that appear to have been borrowed from or influenced by the [[Greek alphabet]] and the [[Hebrew alphabet]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Asian alphabets=== | ||

| + | Beyond the logographic [[Written Chinese|Chinese writing]], many phonetic scripts are in existence in Asia. The [[Arabic alphabet]], [[Hebrew alphabet]], [[Syriac alphabet]], and other [[abjad]]s of the Middle East are developments of the [[Aramaic alphabet]], but because these writing systems are largely [[consonant]]-based they are often not considered true alphabets. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Most alphabetic scripts of India and Eastern Asia are descended from the [[Brahmi script]], which is often believed to be a descendent of Aramaic, but this link is controversial. These scripts are [[abugida]]s, that is, they write syllables instead of individual sounds, so their status as alphabets is disputed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Korea, the [[Hangeul]] alphabet was created, although it may also have been derived from the Mongolian [[Phagspa script]], which in turn was derived from the Brahmi script. Hangeul is a unique alphabet in a variety of ways: many of the letters are designed off of a sound's place of articulation, it was consciously designed by the government at the time, and it situates individual letters into syllable clusters with equal dimensions as [[Chinese characters]] to allow for mixed script writing. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Zhuyin]] (sometimes called ''Bopomofo'') is an alphabet used to phonetically transcribe [[Mandarin (linguistics)|Mandarin Chinese]] in Mainland China and Taiwan, though its use in Mainland China today is limited. It developed out of a form of Chinese shorthand based on Chinese characters in the early 1900s. While Zhuyin is not used as a mainstream writing system, it is still often used in ways similar to a [[romanization]] system—that is, for aiding in pronunciation and as an input method for Chinese characters on computers and cell phones. | ||

| + | |||

| + | European alphabets, especially Latin and Cyrillic, have been adapted for many languages of Asia. Arabic is also widely used, sometimes as an abjad (as with [[Urdu alphabet|Urdu]] and [[Persian alphabet|Persian]]) and sometimes as a complete alphabet (as with [[Kurdish alphabet|Kurdish]] and [[Uyghur alphabet|Uyghur]]). | ||

==Types== | ==Types== | ||

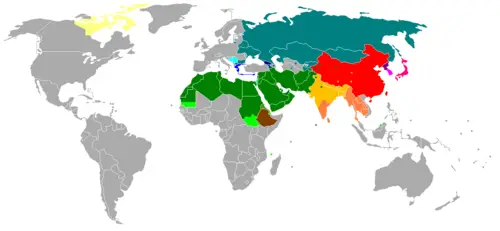

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Writing systems worldwide.png|500px|thumb|'''Alphabets:''' |

| − | + | <span style="background-color:#AAAAAA;color:black;"> Latin </span>, | |

| + | <span style="background-color:#008080;color:white;"> Cyrillic </span>, | ||

| + | <span style="background-color:cyan;color:black;"> Latin and Cyrillic </span>, | ||

| + | <span style="background-color:blue;color:white;"> Greek </span>, | ||

| + | <span style="background-color:darkblue;color:white;"> Armenian or Georgian </span> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | '''Abjads:''' | ||

| + | <span style="background-color:green;color:white;"> Arabic </span>, | ||

| + | <span style="background-color:#66FF00;color:black;"> Arabic and Latin </span>, | ||

| + | <span style="background-color:#00ff7f;color:black;"> Hebrew and Arabic </span> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | '''Abugidas:''' | ||

| + | <span style="background-color:#FFC000;color:black;"> North Indic </span>, | ||

| + | <span style="background-color:orange;color:black;"> South Indic </span>, | ||

| + | <span style="background-color:#800000;color:white;"> Ethiopic </span>, | ||

| + | <span style="background-color:olive;color:white;"> Thaana </span> | ||

| + | <span style="background-color:#FFFF80;color:black;"> Canadian Syllabic </span>, | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | '''Logographic+syllabic:''' | ||

| + | <span style="background-color:red;color:white;"> Pure logographic </span>, | ||

| + | <span style="background-color:#DC143C;color:white;"> Mixed logographic and syllabaries </span>, | ||

| + | <span style="background-color:#FF00FF;color:black;"> Featural-alphabetic syllabary + limited logographic </span> | ||

| + | <span style="background-color:#800080;color:white;"> Featural-alphabetic syllabary </span> ]] | ||

| − | The term "alphabet" is used by [[ | + | The term "alphabet" is used by [[Linguistics|linguists]] and [[paleographer]]s in both a wide and narrow sense. In the wider sense, an alphabet is a script that is ''segmental'' on the [[phoneme]] level, that is, that has separate glyphs for individual sounds and not for larger units such as syllables or words. In the narrower sense, some scholars distinguish "true" alphabets from two other types of segmental script, [[abjad]]s and [[abugida]]s. These three differ from each other in the way they treat vowels: Abjads have letters for consonants and leave most vowels unexpressed; abugidas are also consonant-based, but indicate vowels with [[diacritic]]s to or a systematic graphic modification of the consonants. In alphabets in the narrow sense, on the other hand, consonants and vowels are written as independent letters. The earliest known alphabet in the wider sense is the [[Middle Bronze Age alphabets|Wadi el-Hol script]], believed to be an abjad, which through its successor [[Phoenician alphabet|Phoenician]] is the ancestor of modern alphabets, including [[Arabic alphabet|Arabic]], [[Greek alphabet|Greek]], [[Latin alphabet|Latin]] (via the [[Old Italic alphabet]]), [[Cyrillic alphabet|Cyrillic]] (via the Greek alphabet) and [[Hebrew alphabet|Hebrew]] (via Aramaic). |

Examples of present-day abjads are the [[Arabic script|Arabic]] and [[Hebrew script]]s; true alphabets include [[Latin alphabet|Latin]], [[Cyrillic]], and Korean [[Hangul]]; and abugidas are used to write [[tigrinya language|Tigrinya]] [[Amharic language|Amharic]], [[Hindi language|Hindi]], and [[Thai language|Thai]]. The [[Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics]] are also an abugida rather than a syllabary as their name would imply, since each glyph stands for a consonant which is modified by rotation to represent the following vowel. (In a true syllabary, each consonant-vowel combination would be represented by a separate glyph.) | Examples of present-day abjads are the [[Arabic script|Arabic]] and [[Hebrew script]]s; true alphabets include [[Latin alphabet|Latin]], [[Cyrillic]], and Korean [[Hangul]]; and abugidas are used to write [[tigrinya language|Tigrinya]] [[Amharic language|Amharic]], [[Hindi language|Hindi]], and [[Thai language|Thai]]. The [[Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics]] are also an abugida rather than a syllabary as their name would imply, since each glyph stands for a consonant which is modified by rotation to represent the following vowel. (In a true syllabary, each consonant-vowel combination would be represented by a separate glyph.) | ||

| − | The boundaries between the three types of segmental scripts are not always clear-cut. For example, Iraqi [[Kurdish language|Kurdish]] is written in the [[Arabic script]], which is normally an abjad. However, in Kurdish, writing the vowels is mandatory, and full letters are used, so the script is a true alphabet. Other languages may use a Semitic abjad with mandatory vowel diacritics, effectively making them abugidas. On the other hand, the [[ | + | The boundaries between the three types of segmental scripts are not always clear-cut. For example, Iraqi [[Kurdish language|Kurdish]] is written in the [[Arabic script]], which is normally an abjad. However, in Kurdish, writing the vowels is mandatory, and full letters are used, so the script is a true alphabet. Other languages may use a Semitic abjad with mandatory vowel diacritics, effectively making them abugidas. On the other hand, the [[Phagspa script]] of the [[Mongol Empire]] was based closely on the [[Tibetan script|Tibetan abugida]], but all vowel marks were written after the preceding consonant rather than as diacritic marks. Although short ''a'' was not written, as in the Indic abugidas, one could argue that the linear arrangement made this a true alphabet. Conversely, the vowel marks of the [[Ge'ez alphabet|Tigrinya abugida]] and the Amharic abugida (ironically, the original source of the term "abugida") have been so completely assimilated into their consonants that the modifications are no longer systematic and have to be learned as a [[syllabary]] rather than as a segmental script. Even more extreme, the Pahlavi abjad eventually became [[logogram|logographic]]. (See below.) |

| − | Thus the primary [[Categorisation|classification]] of alphabets reflects how they treat vowels. For [[Tone (linguistics)|tonal languages]], further classification can be based on their treatment of tone, though | + | Thus the primary [[Categorisation|classification]] of alphabets reflects how they treat vowels. For [[Tone (linguistics)|tonal languages]], further classification can be based on their treatment of tone, though names do not yet exist to distinguish the various types. Some alphabets disregard tone entirely, especially when it does not carry a heavy functional load, as in [[Somali language|Somali]] and many other languages of Africa and the Americas. Such scripts are to tone what abjads are to vowels. Most commonly, tones are indicated with diacritics, the way vowels are treated in abugidas. This is the case for [[Vietnamese alphabet|Vietnamese]] (a true alphabet) and [[Thai alphabet|Thai]] (an abugida). In Thai, tone is determined primarily by the choice of consonant, with diacritics for disambiguation. In the [[Sam Pollard|Pollard script]], an abugida, vowels are indicated by diacritics, but the placement of the diacritic relative to the consonant is modified to indicate the tone. More rarely, a script may have separate letters for tones, as is the case for [[Hmong pronunciation|Hmong]] and [[Zhuang language|Zhuang]]. For most of these scripts, regardless of whether letters or diacritics are used, the most common tone is not marked, just as the most common vowel is not marked in Indic abugidas; it [[Zhuyin]] not only is one of the tones unmarked, but there is a diacritic to indicate lack of tone, like the [[virama]] of Indic. |

| − | + | The number of letters in an alphabet can be quite small. The Book [[Pahlavi]] script, an abjad, had only twelve letters at one point, and may have had even fewer later on. Today the [[Rotokas alphabet]] has only twelve letters. (The [[Hawaiian language|Hawaiian]] alphabet is sometimes claimed to be as small, but it actually consists of 18 letters, including the [[Okina|ʻokina]] and five long vowels.) While Rotokas has a small alphabet because it has few phonemes to represent (just eleven), Book Pahlavi was small because many letters had been ''conflated,'' that is, the graphic distinctions had been lost over time, and diacritics were not developed to compensate for this as they were in [[Arabic alphabet|Arabic]], another script that lost many of its distinct letter shapes. For example, a comma-shaped letter represented ''g, d, y, k,'' or ''j''. However, such apparent simplifications can perversely make a script more complicated. In later Pahlavi [[papyrus|papyri]], up to half of the remaining graphic distinctions of these twelve letters were lost, and the script could no longer be read as a sequence of letters at all, but instead each word had to be learned as a whole – that is, they had become [[logogram]]s as in Egyptian [[Demotic Egyptian|Demotic]]. | |

The largest segmental script is probably an abugida, [[Devanagari]]. When written in Devanagari, Vedic [[Sanskrit]] has an alphabet of 53 letters, including the ''visarga'' mark for final aspiration and special letters for ''kš'' and ''jñ,'' though one of the letters is theoretical and not actually used. The Hindi alphabet must represent both Sanskrit and modern vocabulary, and so has been expanded to 58 with the ''khutma'' letters (letters with a dot added) to represent sounds from Persian and English. | The largest segmental script is probably an abugida, [[Devanagari]]. When written in Devanagari, Vedic [[Sanskrit]] has an alphabet of 53 letters, including the ''visarga'' mark for final aspiration and special letters for ''kš'' and ''jñ,'' though one of the letters is theoretical and not actually used. The Hindi alphabet must represent both Sanskrit and modern vocabulary, and so has been expanded to 58 with the ''khutma'' letters (letters with a dot added) to represent sounds from Persian and English. | ||

| Line 54: | Line 172: | ||

Syllabaries typically contain 50 to 400 glyphs (though the [[Múra-Pirahã]] language of [[Brazil]] would require only 24 if it did not denote tone, and Rotokas would require only 30), and the glyphs of logographic systems typically number from the many hundreds into the thousands. Thus a simple count of the number of distinct symbols is an important clue to the nature of an unknown script. | Syllabaries typically contain 50 to 400 glyphs (though the [[Múra-Pirahã]] language of [[Brazil]] would require only 24 if it did not denote tone, and Rotokas would require only 30), and the glyphs of logographic systems typically number from the many hundreds into the thousands. Thus a simple count of the number of distinct symbols is an important clue to the nature of an unknown script. | ||

| − | It is not always clear what constitutes a distinct alphabet. [[French language|French]] uses the same basic alphabet as English, but many of the letters can carry additional marks, such as é, à, and ô. In French, these combinations are not considered to be additional letters. However, in [[Icelandic language|Icelandic]], the accented letters such as á, í, and ö are considered to be distinct letters of the alphabet. In Spanish, ñ is considered a separate letter, but accented vowels such as á and é are not. Some adaptations of the Latin alphabet are augmented with [[ligature (typography)|ligatures]], such as [[æ]] in [[Old English language|Old English]] and [[Ou (letter)|Ȣ]] in [[Algonquian language|Algonquian]]; by borrowings from other alphabets, such as the [[thorn (letter)|thorn]] þ in | + | It is not always clear what constitutes a distinct alphabet. [[French language|French]] uses the same basic alphabet as English, but many of the letters can carry additional marks, such as é, à, and ô. In French, these combinations are not considered to be additional letters. However, in [[Icelandic language|Icelandic]], the accented letters such as á, í, and ö are considered to be distinct letters of the alphabet. In Spanish, ñ is considered a separate letter, but accented vowels such as á and é are not. Some adaptations of the Latin alphabet are augmented with [[ligature (typography)|ligatures]], such as [[æ]] in [[Old English language|Old English]] and [[Ou (letter)|Ȣ]] in [[Algonquian language|Algonquian]]; by borrowings from other alphabets, such as the [[thorn (letter)|thorn]] þ in Old English and Icelandic, which came from the [[Runic alphabet|Futhark]] runes; and by modifying existing letters, such as the [[Eth (letter)|eth]] ð of Old English and Icelandic, which is a modified ''d''. Other alphabets only use a subset of the Latin alphabet, such as Hawaiian, or [[Italian language|Italian]], which only uses the letters ''j, k, x, y'' and ''w'' in foreign words. |

==Spelling== | ==Spelling== | ||

| + | |||

{{details|Spelling}} | {{details|Spelling}} | ||

| Line 66: | Line 185: | ||

* A language may represent the same phoneme with two different letters or combinations of letters. | * A language may represent the same phoneme with two different letters or combinations of letters. | ||

* A language may spell some words with unpronounced letters that exist for historical or other reasons. | * A language may spell some words with unpronounced letters that exist for historical or other reasons. | ||

| − | * Pronunciation of individual words may change according to the presence of surrounding words in a sentence. | + | * Pronunciation of individual words may change according to the presence of surrounding words in a sentence ([[sandhi]]). |

* Different dialects of a language may use different phonemes for the same word. | * Different dialects of a language may use different phonemes for the same word. | ||

| − | * A language may use different sets of symbols or different rules for distinct sets of vocabulary items | + | * A language may use different sets of symbols or different rules for distinct sets of vocabulary items, such as the Japanese [[hiragana]] and [[katakana]] syllabaries, or the various rules in English for spelling words from Latin and Greek, or the original [[Germanic languages|Germanic]] vocabulary. |

National languages generally elect to address the problem of dialects by simply associating the alphabet with the national standard. However, with an international language with wide variations in its dialects, such as [[English language|English]], it would be impossible to represent the language in all its variations with a single phonetic alphabet. | National languages generally elect to address the problem of dialects by simply associating the alphabet with the national standard. However, with an international language with wide variations in its dialects, such as [[English language|English]], it would be impossible to represent the language in all its variations with a single phonetic alphabet. | ||

| − | Some national languages like [[Finnish language|Finnish]] have a very regular spelling system with a nearly one-to-one correspondence between letters and phonemes. The [[Italian language|Italian]] verb corresponding to 'spell', ''compitare'', is unknown to many Italians because the act of spelling itself is almost never needed: each phoneme of Standard Italian is represented in only one way. However, pronunciation cannot always be predicted from spelling because certain letters are pronounced in more than one way. In standard Spanish, it is possible to tell the pronunciation of a word from its spelling, but not vice versa; this is because certain phonemes can be represented in more than one way, but a given letter is consistently pronounced. [[French language|French]], with its [[silent letter]]s and its heavy use of [[nasal vowel]]s and [[elision]], may seem to lack much correspondence between spelling and pronunciation, but its rules on pronunciation are actually consistent and predictable with a fair degree of accuracy | + | Some national languages like [[Finnish language|Finnish]] have a very regular spelling system with a nearly one-to-one correspondence between letters and phonemes. The [[Italian language|Italian]] verb corresponding to 'spell', ''compitare'', is unknown to many Italians because the act of spelling itself is almost never needed: each phoneme of Standard Italian is represented in only one way. However, pronunciation cannot always be predicted from spelling because certain letters are pronounced in more than one way. In standard Spanish, it is possible to tell the pronunciation of a word from its spelling, but not vice versa; this is because certain phonemes can be represented in more than one way, but a given letter is consistently pronounced. [[French language|French]], with its [[silent letter]]s and its heavy use of [[nasal vowel]]s and [[elision]], may seem to lack much correspondence between spelling and pronunciation, but its rules on pronunciation are actually consistent and predictable with a fair degree of accuracy. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | At the other extreme, however, are languages such as English, where the spelling of many words simply has to be memorized as they do not correspond to sounds in a consistent way. For English, this is because the [[Great Vowel Shift]] occurred after the orthography was established, and because English has acquired a large number of loanwords at different times retaining their original spelling at varying levels. However, even English has general rules that predict pronunciation from spelling, and these rules are successful most of the time. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Sometimes, countries have the written language undergo a [[spelling reform]] in order to realign the writing with the contemporary spoken language. These can range from simple spelling changes and word forms to switching the entire writing system itself, as when [[Turkey]] switched from the Arabic alphabet to the Roman alphabet. | |

| − | + | The sounds of speech of all languages of the world can be written by a rather small universal phonetic alphabet. A standard for this is the [[International Phonetic Alphabet]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{reflist}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Bibliography== | ||

* {{cite book | author=Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William | title=The World's Writing Systems | publisher=Oxford University Press | year=1996 | id=ISBN 0-19-507993-0 }} — (Overview of modern and some ancient writing systems). | * {{cite book | author=Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William | title=The World's Writing Systems | publisher=Oxford University Press | year=1996 | id=ISBN 0-19-507993-0 }} — (Overview of modern and some ancient writing systems). | ||

* {{cite book | author=Driver, G.R. | title=Semitic Writing (Schweich Lectures on Biblical Archaeology S.) 3Rev Ed | publisher=Oxford University Press | year=1976 | id=ISBN 0-19-725917-0 }} | * {{cite book | author=Driver, G.R. | title=Semitic Writing (Schweich Lectures on Biblical Archaeology S.) 3Rev Ed | publisher=Oxford University Press | year=1976 | id=ISBN 0-19-725917-0 }} | ||

* {{cite book | author=Hoffman, Joel M. | title=In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language | url = http://www.newjewishbooks.org/ITB/toc.html | publisher=NYU Press | year=2004 | id=ISBN 0-8147-3654-8 }} — (Chapter 3 traces and summarizes the invention of alphabetic writing). | * {{cite book | author=Hoffman, Joel M. | title=In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language | url = http://www.newjewishbooks.org/ITB/toc.html | publisher=NYU Press | year=2004 | id=ISBN 0-8147-3654-8 }} — (Chapter 3 traces and summarizes the invention of alphabetic writing). | ||

| − | * {{cite book | author=Logan, Robert K. | title=The Alphabet Effect: A Media Ecology Understanding of the Making of Western Civilization | publisher=Hampton Press | year=2004 | id=ISBN 1- | + | * {{cite book | author=Logan, Robert K. | title=The Alphabet Effect: A Media Ecology Understanding of the Making of Western Civilization | publisher=Hampton Press | year=2004 | id=ISBN 1-57-273523-6 }} |

* McLuhan, Marshall; Logan, Robert K. (1977). Alphabet, Mother of Invention. Etcetera. Vol. 34, pp. 373-383. | * McLuhan, Marshall; Logan, Robert K. (1977). Alphabet, Mother of Invention. Etcetera. Vol. 34, pp. 373-383. | ||

* {{cite book | author=Ouaknin, Marc-Alain; Bacon, Josephine | title=Mysteries of the Alphabet: The Origins of Writing | publisher=Abbeville Press | year=1999 | id=ISBN 0-7892-0521-1 }} | * {{cite book | author=Ouaknin, Marc-Alain; Bacon, Josephine | title=Mysteries of the Alphabet: The Origins of Writing | publisher=Abbeville Press | year=1999 | id=ISBN 0-7892-0521-1 }} | ||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Powell, Barry | title=Homer and the Origin of the Greek Alphabet | publisher=Cambridge Universityh Press | year=1991 | id=ISBN 0-521-58907-X }} | ||

* {{cite book | author=Sacks, David | title=Letter Perfect: The Marvelous History of Our Alphabet from A to Z | publisher=Broadway Books | year=2004 | id=ISBN 0-7679-1173-3}} | * {{cite book | author=Sacks, David | title=Letter Perfect: The Marvelous History of Our Alphabet from A to Z | publisher=Broadway Books | year=2004 | id=ISBN 0-7679-1173-3}} | ||

* {{cite book | author=Saggs, H.W.F | title=Civilization Before Greece and Rome | publisher=Yale University Press | year=1991 | id=ISBN 0-300-05031-3}} — (Chapter 4 traces the invention of writing). | * {{cite book | author=Saggs, H.W.F | title=Civilization Before Greece and Rome | publisher=Yale University Press | year=1991 | id=ISBN 0-300-05031-3}} — (Chapter 4 traces the invention of writing). | ||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Coulmas, Florian | title=The Writing Systems of the World | publisher=Blackwell Publishers Ltd. | year=1989 | id=ISBN 0-631-18028-1 }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | * David Diringer, ''History of the Alphabet'', 1977, ISBN 0-905418-12-3. | ||

| + | * Peter T. Daniels, William Bright (eds.), 1996. ''The World's Writing Systems'', ISBN 0-19-507993-0. | ||

| + | * Joel M. Hoffman, ''In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language'', 2004, ISBN 0-8147-3654-8. | ||

| + | * Robert K. Logan, ''The Alphabet Effect: The Impact of the Phonetic Alphabet on the Development of Western Civilization'', New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1986. | ||

| + | * B.L. Ullman, "The Origin and Development of the Alphabet," ''American Journal of Archaeology'' 31, No. 3 (Jul., 1927): 311-328. | ||

| + | * Stephen R. Fischer, ''A History of Writing'' 2005 Reaktion Books CN 136481 | ||

| + | |||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

* [http://omniglot.com/writing/alphabetic.htm Alphabetic Writing Systems] | * [http://omniglot.com/writing/alphabetic.htm Alphabetic Writing Systems] | ||

| − | * | + | * Michael Everson's [http://www.evertype.com/alphabets/index.html Alphabets of Europe] |

| − | |||

* [http://www.wam.umd.edu/~rfradkin/alphapage.html Evolution of alphabets] animation by Prof. Robert Fradkin at the University of Maryland | * [http://www.wam.umd.edu/~rfradkin/alphapage.html Evolution of alphabets] animation by Prof. Robert Fradkin at the University of Maryland | ||

| − | * [http://www. | + | * [http://www.nonstopmasti.info/2006/11/10/how-alphabets-evolved/ History of alphabet] |

| − | + | *[http://www.childrenofthecode.org/Tour/c5/bigbang.htm Online Video: The Alphabet's Big Bang] | |

| − | *[http://www. | ||

| − | |||

| + | * [http://www.wam.umd.edu/~rfradkin/alphapage.html Animated examples of how the English alphabet evolved] | ||

| + | * [http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A216073 BBC site for the Greek alphabet] | ||

| + | * [http://www.greek-language.com/alphabet/ Site by a scholar about the Greek alphabet] | ||

| + | * [http://www.grecoreport.com/phoenician.htm Article republished from an Athenian newspaper] | ||

| + | * [http://www.cedarland.org/alpha.html Information about the alphabet’s evolution from a site about Lebanon] | ||

| + | * [http://www.ling.lu.se/education/homepages/ALS061/DEMO/INTR3/IntroScript.html Information about the Georgian Script] | ||

| + | *[http://www.cartage.org.lb/en/themes/geoghist/histories/oldcivilization/phoenicia/phoenicianalphabet/familytree.html An alphabetic 'family tree']. | ||

| − | {{Credits|Alphabet| | + | {{Credits|Alphabet|168824611|History_of_the_alphabet|163992831|}} |

Revision as of 20:52, 3 November 2007

Writing systems |

|---|

| History |

| Types |

| Alphabet |

| Abjad |

| Abugida |

| Syllabary |

| Logogram |

| Related |

| Pictogram |

| Ideogram |

An alphabet is a standardized set of letters — basic written symbols — each of which roughly represents a phoneme of a spoken language, either as it exists now or as it was in the past. There are other systems of writing such as logographies, in which each character represents a word, and syllabaries, in which each character represents a syllable, but alphabets are the most widespread writing system. Alphabets are in turn classified according to how they indicate vowels: as equal to consonants, as in Greek, as modifications of consonants, as in Hindi, or not at all, as in Arabic.

The word "alphabet" came into Middle English from the Late Latin Alphabetum, which in turn originated in the Ancient Greek Alphabetos, from alpha and beta, the first two letters of the Greek alphabet.[1] There are dozens of alphabets in use today. Most of them are composed of lines (linear writing); notable exceptions are Braille, fingerspelling, and Morse code.

Linguistic definition and context

The term alphabet prototypically refers to a writing system that has characters (graphemes) for representing both consonant and vowel sounds, even though there may not be a complete one-to-one correspondence between symbol and sound.

A grapheme is an abstract entity which may be physically represented by different styles of glyphs. There are many written entities which do not form part of the alphabet, including numerals, mathematical symbols, and punctuation. Some human languages are commonly written by using a combination of logograms (which represent morphemes or words) and syllabaries (which represent syllables) instead of an alphabet. Egyptian hieroglyphs and Chinese characters are two of the best-known writing systems with predominantly non-alphabetic representations.

Non-written languages may also be represented alphabetically. For example, linguists researching a non-written language (such as some of the indigenous Amerindian languages) will use the International Phonetic Alphabet to enable them to write down the sounds they hear.

Most, if not all, linguistic writing systems have some means for phonetic approximation of foreign words, usually using the native character set.[2]

History

Egyptian hieroglyphs 32 c. BCE

- Hieratic 32 c. BCE

- Demotic 7 c. BCE

- Meroitic 3 c. BCE

- Demotic 7 c. BCE

- Proto-Sinaitic 19 c. BCE

- Ugaritic 15 c. BCE

- Epigraphic South Arabian 9 c. BCE

- Ge’ez 5–6 c. BCE

- Phoenician 12 c. BCE

- Paleo-Hebrew 10 c. BCE

- Samaritan 6 c. BCE

- Libyco-Berber 3 c. BCE

- Tifinagh

- Paleohispanic (semi-syllabic) 7 c. BCE

- Aramaic 8 c. BCE

- Kharoṣṭhī 4 c. BCE

- Brāhmī 4 c. BCE

- Brahmic family (see)

- E.g. Tibetan 7 c. CE

- Hangul (core letters only) 1443

- Devanagari 13 c. CE

- Canadian syllabics 1840

- E.g. Tibetan 7 c. CE

- Brahmic family (see)

- Hebrew 3 c. BCE

- Pahlavi 3 c. BCE

- Avestan 4 c. CE

- Palmyrene 2 c. BCE

- Syriac 2 c. BCE

- Nabataean 2 c. BCE

- Arabic 4 c. CE

- Sogdian 2 c. BCE

- Nabataean 2 c. BCE

- Orkhon (old Turkic) 6 c. CE

- Old Hungarian c. 650

- Old Uyghur

- Mongolian 1204

- N'Ko 20 c. CE

- Old Uyghur

- Old Hungarian c. 650

- Mandaic 2 c. CE

- Greek 8 c. BCE

- Etruscan 8 c. BCE

- Latin 7 c. BCE

- Cherokee (syllabary; letter forms only) c. 1820

- Runic 2 c. CE

- Ogham (origin uncertain) 4 c. CE

- Latin 7 c. BCE

- Coptic 3 c. CE

- Gothic 3 c. CE

- Armenian (origin uncertain) 405

- Georgian (origin uncertain) c. 430

- Glagolitic (origin uncertain) 862

- Cyrillic c. 940

- Old Permic 1372

- Etruscan 8 c. BCE

- Paleo-Hebrew 10 c. BCE

Thaana 18 c. (derived from Brahmi numerals)

The history of the alphabet begins in Ancient Egypt, more than a millennium into the history of writing. The first pure alphabet emerged around 2000 B.C.E. to represent the language of Semitic workers in Egypt (see Middle Bronze Age alphabets), and was derived from the alphabetic principles of the Egyptian hieroglyphs. Most alphabets in the world today either descend directly from this development, for example the Greek and Latin alphabets, or were inspired by its design. [3]

Pre-alphabetic scripts

Two scripts are well attested from before the end of the fourth millennium B.C.E.: Mesopotamian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs. Both were well known in the part of the Middle East that produced the first widely used alphabet, the Phoenician. There are signs that cuneiform was developing alphabetic properties in some of the languages it was adapted for, as was seen again later in the Old Persian cuneiform script, but it now appears these developments were a sideline and not ancestral to the alphabet.

The Beginnings in Egypt

By 2700 B.C.E. the ancient Egyptians had developed a set of some 22 hieroglyphs to represent the individual consonants of their language, plus a 23rd that seems to have represented word-initial or word-final vowels. These glyphs were used as pronunciation guides for logograms, to write grammatical inflections, and, later, to transcribe loan words and foreign names. However, although alphabetic in nature, the system was not used for purely alphabetic writing. That is, while capable of being used as an alphabet, it was in fact always used with a strong logographic component, presumably due to strong cultural attachment to the complex Egyptian script. The first purely alphabetic script is thought to have been developed around 2000 B.C.E. for Semitic workers in central Egypt. Over the next five centuries it spread north, and all subsequent alphabets around the world have either descended from it, or been inspired by one of its descendants, with the possible exception of the Meroitic alphabet, a 3rd century B.C.E. adaptation of hieroglyphs in Nubia to the south of Egypt - though even here many scholars suspect the influence of that first alphabet.[citation needed]

The Semitic alphabet

The Middle Bronze Age scripts of Egypt have yet to be deciphered. However, they appear to be at least partially, and perhaps completely, alphabetic. The oldest examples are found as graffiti from central Egypt and date to around 1800 B.C.E. [1]/[2]. [4] These inscriptions, according to Gordon J. Hamilton, help to show that the most likely place for the alphabet’s invention was in Egypt proper. [5]

This Semitic script did not restrict itself to the existing Egyptian consonantal signs, but incorporated a number of other Egyptian hieroglyphs, for a total of perhaps thirty, and used Semitic names for them.[6] So, for example, the hieroglyph per ("house" in Egyptian) became bayt ("house" in Semitic).[7] It is unclear at this point whether these glyphs, when used to write the Semitic language, were purely alphabetic in nature, representing only the first consonant of their names according to the acrophonic principle, or whether they could also represent sequences of consonants or even words as their hieroglyphic ancestors had. For example, the "house" glyph may have stood only for b (b as in beyt "house"), or it may have stood for both the consonant b and the sequence byt, as it had stood for both p and the sequence pr in Egyptian. However, by the time the script was inherited by the Canaanites, it was purely alphabetic, and the hieroglyph originally representing "house" stood only for b.[8]

The first Canaanite state to make extensive use of the alphabet was Phoenicia, and so later stages of the Canaanite script are called Phoenician. Phoenicia was a maritime state at the center of a vast trade network, and soon the Phoenician alphabet spread throughout the Mediterranean. [3] Two variants of the Phoenician alphabet would have major impacts on the history of writing: the Aramaic alphabet and the Greek alphabet. [4]

Descendants of the Aramaic abjad

The Phoenician and Aramaic alphabets, like their Egyptian prototype, represented only consonants, a system called an abjad. The Aramaic alphabet, which evolved from the Phoenician in the 7th century B.C.E. as the official script of the Persian Empire, appears to be the ancestor of nearly all the modern alphabets of Asia:[citation needed]

- The modern Hebrew alphabet started out as a local variant of Imperial Aramaic. (The original Hebrew alphabet has been retained by the Samaritans.) [9] [10]

- The Arabic alphabet descended from Aramaic via the Nabatean alphabet of what is now southern Jordan.

- The Syriac alphabet used after the 3rd century CE evolved, through Pahlavi and Sogdian, into the alphabets of northern Asia, such as Orkhon (probably), Uyghur, Mongolian, and Manchu.

- The Georgian alphabet is of uncertain provenance, but appears to be part of the Persian-Aramaic (or perhaps the Greek) family.

- The Aramaic alphabet is also the most likely ancestor of the Brahmic alphabets of the Indian subcontinent, which spread to Tibet, Mongolia, Indochina, and the Malay archipelago along with the Hindu and Buddhist religions. (China and Japan, while absorbing Buddhism, were already literate and retained their logographic and syllabic scripts.)

- The Hangul alphabet was invented in Korea in the 15th century. Tradition holds that it was an autonomous invention; however, Gari Ledyard suggests that portions of its consonantal system may be based on half a dozen letters derived from Tibetan via the imperial Phagspa alphabet of the Yuan dynasty of China; Tibetan is a Brahmic script. Uniquely among the world's alphabets, the rest of the consonants are derived from this core as a featural system.[citation needed]

Transmission of the Alphabet to Greece

By at least the 8th century B.C.E. the Greeks borrowed the Phoenician alphabet and adapted it to their own language.[11] The letters of the Greek alphabet are the same as those of the Phoenician alphabet, and both alphabets are arranged in the same order. [12] However, whereas separate letters for vowels would have actually hindered the legibility of Egyptian, Phoenician, or Hebrew, their absence was problematic for Greek, where vowels played a much more important role. The Greeks adapted those Phoenician letters for consonants they couldn't pronounce to write vowels. All of the names of the letters of the Phoenician alphabet started with consonants, and these consonants were what the letters represented, something called the acrophonic principle. However, several Phoenician consonants were rather soft and unpronounceable by the Greeks, and thus several letter names came to be pronounced with initial vowels. Since the start of the name of a letter was expected to be the sound of the letter, in Greek these letters now stood for vowels.[citation needed] For example, the Greeks had no glottal stop or h, so the Phoenician letters ’alep and he became Greek alpha and e (later renamed e psilon), and stood for the vowels /a/ and /e/ rather than the consonants /ʔ/ and /h/. As this fortunate development only provided for five or six (depending on dialect) of the twelve Greek vowels, the Greeks eventually created digraphs and other modifications, such as ei, ou, and o (which became omega), or in some cases simply ignored the deficiency, as in long a, i, u. [13]

Several varieties of the Greek alphabet developed. One, known as Western Greek or Chalcidian, was west of Athens and in southern Italy. The other variation, known as Eastern Greek, was used in present-day Turkey, and the Athenians, and eventually the rest of the world that spoke Greek, adopted this variation. After first writing right to left, the Greeks eventually chose to write from left to right, unlike the Phoenicians who wrote from right to left. [5]

Descendants of the Greek Alphabet

Greek is in turn the source for all the modern scripts of Europe. The alphabet of the early western Greek dialects, where the letter eta remained an h, gave rise to the Old Italic and Roman alphabets. In the eastern Greek dialects, which did not have an /h/, eta stood for a vowel, and remains a vowel in modern Greek and all other alphabets derived from the eastern variants: Glagolitic, Cyrillic, Armenian, Gothic (which used both Greek and Roman letters), and perhaps Georgian.[14] [15]

Although this description presents the evolution of scripts in a linear fashion, this is a simplification. For example, the Manchu alphabet, descended from the abjads of West Asia, was also influenced by Korean hangul, which was either independent (the traditional view) or derived from the abugidas of South Asia. Georgian apparently derives from the Aramaic family, but was strongly influenced in its conception by Greek. The Greek alphabet, itself ultimately a derivative of hieroglyphs through that first Semitic alphabet, later adopted an additional half dozen demotic hieroglyphs when it was used to write Coptic Egyptian. Then there is Cree Syllabics (an abugida), which appears to be a fusion of Devanagari and Pitman shorthand; the latter may be an independent invention, but likely has its ultimate origins in cursive Latin script. [citation needed]

Development of the Roman Alphabet

A tribe known as the Latins, who became known as the Romans, also lived in the Italian peninsula like the Western Greeks. From the Etruscans, a tribe living in the first millennium B.C.E. in central Italy, and the Western Greeks, the Latins adopted writing in about the fifth century. In adopted writing from these two groups, the Latins dropped four characters from the Western Greek alphabet. They also adapted the Etruscan letter F, pronounced 'w,' giving it the 'f' sound, and the Etruscan S, which had three zigzag lines, was curved to make the modern S. To represent the G sound in Greek and the K sound in Etruscan, the Gamma was used. These changes produced the modern alphabet without the letters G, J, U, W, Y, and Z, as well as some other differences. [6]

C, K, and Q in the Romans’ alphabet could all be used to write the k sound, and C could also be used to write the sound 'g.' The Romans invented the letter G and inserted it into the alphabet between F and H for an unknown reason. Over the few centuries after Alexander the Great conquered the Eastern Mediterranean and other areas in the third century B.C.E., the Romans began to borrow Greek words, so they had to adapt their alphabet again in order to write these words. From the Eastern Greek alphabet, they borrowed Y and Z, which were added to the end of the alphabet because the only time they were used was to write Greek words. [7]

The Anglo-Saxon language began to be written using Roman letters after Britain was invaded by the Normans in the eleventh century. Because the Runic wen, which was first used to represent the sound 'w' and looked like a p that is narrow and triangular, was easy to confuse with an actual p, the 'w' sound began to be written using a double u. Because the u at the time looked like a v, the double u looked like two v's, W was placed in the alphabet by V. U developed when people began to use the rounded U when they meant the vowel u and the pointed V when the meant the consonant V. J began as a variation of I, in which a long tail was added to the final I when there were several in a row. People began to use the J for the consonant and the I for the vowel by the fifteenth century, and it was fully accepted in the mid-seventeenth century. [8]

Letter Names and Sequence of Some Alphabets

The order of the letters of the alphabet is attested from the fourteenth century B.C.E., in a place called Ugarit located on Syria’s northern coast. [16] Tablets found there bear over one thousand cuneiform signs, but these signs are not Babylonian, and there are only thirty distinct characters. About twelve of the tablets have the signs set out in alphabetic order. There are two orders found, one which is nearly identical to the order used for Hebrew, Greek, and Latin, and a second order very similar to that used for Ethiopian. [17]

It is not known how many letters the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet had, nor what their alphabetic order was. Among its descendants, the Ugaritic alphabet had 27 consonants, the South Arabian alphabets had 29, and the Phoenician alphabet was reduced to 22. These scripts were arranged in two orders, an ABGDE order in Phoenician, and an HMĦLQ order in the south; Ugaritic preserved both orders. Both sequences proved remarkably stable among the descendants of these scripts.

The letter names proved stable among many descendants of Phoenician, including Samaritan, Aramaic, Syriac, Hebrew, and Greek alphabet. However, they were abandoned in Arabic and Latin. The letter sequence continued more or less intact into Latin, Armenian, Gothic, and Cyrillic, but was abandoned in Brahmi, Runic, and Arabic, although a traditional abjadi order remains or was re-introduced as an alternative in the latter. [citation needed]

These 22 consonants account for the phonology of Northwest Semitic.

Graphically independent alphabets

The only modern national alphabet that has not been graphically traced back to the Canaanite alphabet is the Maldivian script, which is unique in that, although it is clearly modeled after Arabic and perhaps other existing alphabets, it derives its letter forms from numerals. The Osmanya alphabet devised for Somali in the 1920s was co-official in Somalia with the Latin alphabet until 1972, and the forms of its consonants appear to be complete innovations.

Among alphabets that are not used as national scripts today, a few are clearly independent in their letter forms. The Zhuyin phonetic alphabet derives from Chinese characters. The Santali alphabet of eastern India appears to be based on traditional symbols such as "danger" and "meeting place," as well as pictographs invented by its creator. (The names of the Santali letters are related to the sound they represent through the acrophonic principle, as in the original alphabet, but it is the final consonant or vowel of the name that the letter represents: le "swelling" represents e, while en "thresh grain" represents n.)

In the ancient world, Ogham consisted of tally marks, and the monumental inscriptions of the Old Persian Empire were written in an essentially alphabetic cuneiform script whose letter forms seem to have been created for the occasion. However, while all of these systems may have been graphically independent of the other alphabets of the world, they were devised from their example. [citation needed]

Alphabets in other media

Changes to a new writing medium sometimes caused a break in graphical form, or make the relationship difficult to trace. It is not immediately obvious that the cuneiform Ugaritic alphabet derives from a prototypical Semitic abjad, for example, although this appears to be the case. And while manual alphabets are a direct continuation of the local written alphabet (both the British two-handed and the French/American one-handed alphabets retain the forms of the Latin alphabet, as the Indian manual alphabet does Devanagari, and the Korean does Hangul), Braille, semaphore, maritime signal flags, and the Morse codes are essentially arbitrary geometric forms. The shapes of the English Braille and semaphore letters, for example, are derived from the alphabetic order of the Latin alphabet, but not from the graphic forms of the letters themselves. Modern shorthand also appears to be graphically unrelated. If it derives from the Latin alphabet, the connection has been lost to history. [citation needed]

Middle Eastern Scripts

The history of the alphabet starts in ancient Egypt. By 2700 BCE Egyptian writing had a set of some 22 hieroglyphs to represent syllables that begin with a single consonant of their language, plus a vowel (or no vowel) to be supplied by the native speaker. These glyphs were used as pronunciation guides for logograms, to write grammatical inflections, and, later, to transcribe loan words and foreign names.[18]