Difference between revisions of "Agape" - New World Encyclopedia

Scott Dunbar (talk | contribs) (Removing unnecessary links) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (166 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{2Copyedited}}{{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | '''' | + | [[File:Chiesa del Nome di Gesù - Venice - Il Sacro Cuore by Lattanzio Querena.jpg|thumb|right|225px|In Christianity, ''agapē'' is associated with the unconditional love of [[Jesus Christ]], depicted here in his [[Sacred Heart]] form.]] |

| − | ''' | + | '''''Agapē''''' (αγάπη in Greek) is one of several Greek words translated into English as [[love]]. Greek writers at the time of [[Plato]] and other ancient authors used forms of the word to denote love of a spouse or [[family]], or affection for a particular activity, in contrast to, if not with a totally separate meaning from, ''[[philia]]'' (an affection that could denote either brotherhood or generally non-sexual affection) and ''[[eros]]'' (an affection of a sexual nature, usually between two unequal partners, although Plato's notion of ''eros'' as love for [[beauty]] is not necessarily sexual). The term ''agape'' with that meaning was rarely used in ancient manuscripts, but quite extensively used in the [[Septuagint]], the Koine Greek translation of the [[Hebrew Bible]]. |

| − | + | In the [[New Testament]], however, ''agape'' was frequently used to mean something more distinctive: the unconditional, self-sacrificing, and volitional love of [[God]] for humans through [[Jesus]], which they ought also to reciprocate by practicing ''agape'' love towards God and among themselves. The term ''agape'' has been expounded on by many [[Christianity|Christian]] writers in a specifically Christian context. In early Christianity, ''agape'' also signified a type of [[Eucharist|eucharistic]] feast shared by members of the community. | |

| − | '' | + | {{toc}} |

| + | The Latin translation of ''agape'' in the [[Vulgate]] is usually ''caritas'', which in older Bibles is sometimes translated "charity." [[St. Augustine]] believed ''caritas'' to contain not only ''agape'' but also ''eros,'' because he thought it includes the human desire to be like God. The [[Sweden|Swedish]] [[Lutheranism|Lutheran]] [[theology|theologian]] [[Anders Nygren]] critiqued the Augustinian theory, sharply distinguishing between ''agape'' (unmotivated by the object) and ''eros'' (motivated and evoked by the object) and regarding ''agape'' as the only purely Christian kind of love. Yet Nygren's theory has been criticized as having an excessively narrow understanding of ''agape'' that is unable to appreciate the relational nature of divine love, as it is often so portrayed in the [[Bible]]. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Greek Words for Love== |

| + | [[Image:baglione.jpg|right|thumb|200px|'Sacred Love versus Profane Love' by Giovanni Baglione]] | ||

| − | + | Ancient Greek distinguishes a number of words for [[love]], of which three are most prominent: ''[[eros (love)|eros]],'' ''[[philia]],'' and ''agape.'' As with other languages, it has been historically difficult to separate the meanings of these words totally. However, the senses in which these words were generally used are given below: | |

| − | + | * '''''Eros''''' ({{polytonic|ἔρως}} ''érōs'') is passionate love and attraction including sensual [[desire]] and longing. It is love more intimate than the ''philia'' love of [[friendship]]. The modern Greek word "''erotas''" means "romantic love," and the ancient Greek word ''eros,'' too, applies to dating relationships and [[marriage]]. The word ''eros'' with the meaning of sexual love appears one time ([[Book of Proverbs|Proverbs]] 7:18) in the [[Septuagint]], the Greek translation of the [[Hebrew Bible]], but it is absent in the Koine Greek text of the [[New Testament]]. ''Eros'' in ancient Greek is not always sexual in nature, however. For [[Plato]], while ''eros'' is initially felt for a person, with [[contemplation]] it becomes an appreciation of the [[beauty]] within that person, or even an appreciation of beauty itself. It should be noted that Plato does not talk of physical attraction as a necessary part of love, hence the use of the word platonic to mean, "without physical attraction." The most famous ancient work on the subject of ''eros'' is Plato's ''Symposium,'' which is a discussion among the students of [[Socrates]] on the nature of ''eros.''<ref>Plato, ''The Symposium,'' tr. Christopher Gill (Penguin Classics, 2003).</ref> Plato says ''eros'' helps the [[soul]] recall [[knowledge]] of beauty, and contributes to an understanding of spiritual [[truth]]. Lovers and [[philosophy|philosopher]]s are all inspired to seek truth by ''eros.'' | |

| − | + | * '''''Philia''''' ({{polytonic|φιλία}} ''philía'') means friendship and dispassionate [[virtue|virtuous]] love. It includes [[loyalty]] to friends, [[family]], and community, and requires virtue, [[equality]] and familiarity. In ancient texts, ''philia'' denotes a general type of love, used for love between friends, and family members, as well as between lovers. This, in its verb or adjective form (i.e., ''phileo'' or ''philos''), is the only other word for "love" used in the New Testament besides ''agape,'' but even then it is used substantially less frequently. | |

| − | + | * '''''Agape''''' ({{polytonic|ἀγάπη}} ''agápē'') refers to a general affection of "love" rather than the attraction suggested by ''eros''; it is used in ancient texts to denote feelings for a good meal, one's children, and one's spouse. It can be described as the feeling of being content or holding one in high regard. This broad meaning of ''agape'' or its verb ''agapao'' can be seen extensively in the Septuagint as the Greek translation of the common Hebrew term for love ''(aḥaba)'', which denotes not only [[God]]'s love for humanity but also one's affection for one's spouse and children, brotherly love, and even sexual [[desire]]. It is uncertain why ''agape'' was chosen, but the similarity of consonant sounds ''(aḥaba)'' may have played a part. This usage provides the context for the choice of this otherwise still quite obscure word, in preference to other more common Greek words, as the most frequently used word for love in the New Testament. But, when it is used in the New Testament, its meaning becomes more focused, mainly referring to unconditional, self-sacrificing, giving love to all—both friend and enemy. | |

| − | + | Additionally, modern Greek contains two other words for love: | |

| − | + | * '''''Storge''''' ({{polytonic|στοργή}} ''storgē'') means "affection"; it is natural affection, like that felt by parents for offspring. The word was rarely used in ancient works, and almost exclusively as a descriptor of relationships within the family. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * '''''Thelema''''' (θέλημα) means "desire"; it is the desire to do something, to be occupied, to be in prominence. | |

| − | === The example of | + | ==''Agape'' in Christianity == |

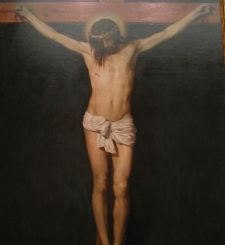

| + | [[Image:Cristo Velázquez lou2.jpg|thumb|right|225px|The ''[[Crucifixion]]'' of Jesus is seen as an example of ''agape'' (self-sacrificing love). Diego Velázquez, seventeenth century]] | ||

| − | + | ===New Testament=== | |

| + | In the [[New Testament]], the word ''agape'' or its verb form ''agapao'' appears more than 200 times. It is used to describe: | ||

| − | + | #[[God]]'s love for [[human being]]s: "God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son ([[Gospel of John|John]] 3:16); "God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us ([[Epistle to the Romans|Romans]] 5:8); "God is love" ([[1 John]] 4:8). | |

| − | + | #[[Jesus]]' love for human beings: "Christ loved us and gave himself up for us as a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God ([[Epistle to the Ephesians|Ephesians]] 5:2). | |

| − | + | #What our love for God should be like: "Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind" ([[Gospel of Matthew|Matthew]] 22:37). | |

| − | + | #What our love for one another as human beings should be like: "Love your neighbor as yourself" (Matthew 22:39); "Love each other as I have loved you" (John 15:12); "Love does no harm to its neighbor. Therefore love is the fulfillment of the law" (Romans 13:10). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ''Agape'' in the New Testament is a form of love that is voluntarily self-sacrificial and gratuitous, and its origin is God. Its character is best described in the following two passages: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you. If someone strikes you on one cheek, turn to him the other also. If someone takes your cloak, do not stop him from taking your tunic. Give to everyone who asks you, and if anyone takes what belongs to you, do not demand it back. Do to others as you would have them do to you. If you love those who love you, what credit is that to you? Even 'sinners' love those who love them. And if you do good to those who are good to you, what credit is that to you? Even 'sinners' do that. And if you lend to those from whom you expect repayment, what credit is that to you? Even 'sinners' lend to 'sinners,' expecting to be repaid in full. But love your enemies, do good to them, and lend to them without expecting to get anything back. Then your reward will be great, and you will be sons of the Most High, because he is kind to the ungrateful and wicked. Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful ([[Gospel of Luke|Luke]] 6:27-36).</blockquote> | |

| − | + | <blockquote>If I speak in the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal. If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have a faith that can move mountains, but have not love, I am nothing. If I give all I possess to the poor and surrender my body to the flames, but have not love, I gain nothing. Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It is not rude, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres ([[1 Corinthians]] 13:1-7).</blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | However, the verb ''agapao'' is at times used also in a negative sense, where it retains its more general meaning of "affection" rather than unconditional love or divine love. Such examples include: "for Demas, because he loved ''(agapao)'' this world, has deserted me and has gone to Thessalonica ([[2 Timothy]] 4:10); "for they loved ''(agapao)'' praise from men more than praise from God (John 12:43); and "Light has come into the world, but men loved ''(agapao)'' darkness instead of light because their deeds were evil (John 3:19). | |

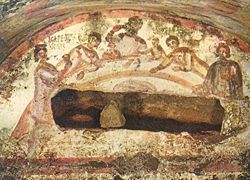

| − | + | [[Image:Agape feast 03.jpg|thumb|250px|[[Fresco]] of a female figure holding a chalice at an early Christian Agape feast. Catacomb of Saints Marcellinus and Peter, Via Labicana, [[Rome]]]] | |

| − | == | + | ===Agape as a meal=== |

| + | The word ''agape'' in its plural form is used in the New Testament to describe a meal or feast eaten by early Christians, as in [[Epistle of Jude|Jude]] 1:12, [[2 Peter]] 2:13, and 1 Corinthians 11:17-34. The ''agape'' meal was either related to the [[Eucharist]] or another term used for the Eucharist.<ref>J. F. Keating. ''The Agape and the Eucharist in the Early Church: Studies in the History of the Christian Love-Feasts.'' (Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007).</ref> It eventually fell into disuse. | ||

| − | + | ===Later Christian development=== | |

| + | Because of the frequent use of the word ''agape'' in the New Testament, Christian writers have developed a significant amount of [[theology]] based solely on the interpretation of it. | ||

| − | + | The Latin translation of ''agape'' is usually ''caritas'' in the [[Vulgate]] and amongst [[Catholicism|Catholic]] theologians such as [[St. Augustine]]. Hence the original meaning of "charity" in English. The [[King James Version]] uses "charity" as well as "love" to translate the idea of ''agape'' or ''caritas.'' When Augustine used the word ''caritas,'' however, he meant by it more than self-sacrificial and gratuitous love because he included in it also the human [[desire]] to be like [[God]] in a [[Plato|Platonic]] way. For him, therefore, ''caritas'' is neither purely ''agape'' nor purely ''eros'' but a synthesis of both. | |

| − | + | The twentieth-century [[Sweden|Swedish]] [[Lutheranism|Lutheran]] theologian [[Anders Nygren]] made a sharp distinction between ''agape'' and ''eros'', saying that the former indicates God's unmerited descent to [[human]]s, whereas the latter shows humans' ascent to God. According to Nygren, ''agape'' and ''eros'' have nothing to do with each other, belonging to two entirely separate realms. The former is divine love that creates and bestows value even on the unlovable object, whereas the latter is [[paganism|pagan]] love that seeks its own fulfillment from any value in the object. The former, being altruistic, is the center of Christianity, whereas the latter is egocentric and non-Christian. Based on this, Nygren critiqued Augustine's notion of ''caritas,'' arguing that it is an illegitimate synthesis of ''eros'' and ''agape,'' distorting the pure, Christian love that is ''agape.'' Again, according to Nygren, ''agape'' is spontaneous, unmotivated by the value of (or its absence in) the object, creative of value in the object, and initiative of God's fellowship, whereas ''eros'' is motivated and evoked by the quality, value, beauty, or worth of the object. Nygren's observation is that ''agape'' in its pure form was rehabilitated through [[Martin Luther]]'s [[Protestant Reformation]].<ref>Anders Nygren. ''Agape and Eros'' (Westminster Press, 1953).</ref> | |

| − | + | In 2006, Pope [[Benedict XVI]] in his first [[encyclical]], ''Deus Caritas Est,'' addressed this issue, saying that ''eros'' and ''agape'' are both inherently good as two separable halves of complete love that is ''caritas,'' although ''eros'' may risk degrading to mere sex without a spiritual support. It means that complete love involves the dynamism between the love of giving and the love of receiving.<ref>[http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/encyclicals/documents/hf_ben-xvi_enc_20051225_deus-caritas-est_en.html Deus Caritas Est.].''Vatican Library''. Retrieved April 30, 2008.</ref> | |

| − | + | ===Criticisms of Nygren=== | |

| + | [[Anders Nygren|Nygren]]'s sharp distinction of ''agape'' and ''eros'' has been criticized by many. Daniel Day Williams, for example, has critiqued Nygren, referring to the [[New Testament]] passage: "Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled" ([[Gospel of Matthew|Matthew]] 5:6). This passage, according to Williams, shows that the two types of [[love]] are related to each other in that [[God]]'s ''agape'' can be given to those who strive for righteousness in their love of ''eros'' for it, and that Nygren's contrasting categorizations of ''agape'' as absolutely unconditional and of ''eros'' as an egocentric desire for fellowship with God do not work.<ref>Daniel Day Williams. ''God's Grace and Man's Hope: An Interpretation of the Christian Life in History.'' (Harper & Row, 1965).</ref> How can our desire for fellowship with God be so egocentric as not to be able to deserve God's grace? | ||

| − | + | Another way of relating ''agape'' to ''eros'' has been suggested by [[process thought|process theologians]]. According to them, the ultimate purpose of ''agape'' is to help create value in the object so that the subject may be able to eventually appreciate and enjoy it through ''eros''. When God decides to unconditionally love us in his attempt to save us, doesn't he at the same time seek to see our salvation eventually? This aspect of God's love which seeks the value of [[beauty]] in the world is called "Eros" by [[Alfred North Whitehead]], who defines it as "the living urge towards all possibilities, claiming the goodness of their realization."<ref>Alfred North Whitehead. ''Adventures of Ideas.'' (Cambridge University Press, 1933), 381.</ref> One significant corollary in this more comprehensive understanding of love is that when the object somehow fails to build value in response, the subject suffers. Hence, process theologians talk about the suffering of God, and argue that it is an important [[Bible|biblical]] theme especially in the [[Hebrew Bible]] that records that God suffered as a "God in Search of Man"—a phrase which is the title of a book written by the Jewish theologian [[Abraham Joshua Heschel]].<ref>Abraham Joshua Heschel. ''God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism.'' (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976).</ref> | |

| − | + | It seems, therefore, that ''agape'' and ''eros'', while distinguishable from each other, are closely connected. Love, as understood this way, applies not only to the mutual relationship between God and humans but also to the reciprocal relationship among humans. It can be recalled that ancient Greek did not share the modern tendency to sharply differentiate between the various terms for love such as ''agape'' and ''eros.'' | |

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| + | * Heschel, Abraham Joshua. ''God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism.'' Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976. ISBN 0374513317 | ||

| + | * Keating, J. F. ''The Agape and the Eucharist in the Early Church: Studies in the History of the Christian Love-Feasts.'' Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007. ISBN 9780548287699 | ||

| + | * Lewis, C. S. ''The Four Loves.'' Fount, 2002. ISBN 0006280897 | ||

| + | * Nygren, Anders. ''Agape and Eros''. Westminster Press, 1953. | ||

| + | * Outka, Gene. ''Agape: An Ethical Analysis (Yale Publications in Religion).'' New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977. ISBN 9780300021226 | ||

| + | * Plato. ''The Symposium,'' Translated by Christopher Gill. Penguin Classics, 2003. ISBN 9780140449273 | ||

| + | * Soble, Alan. ''Eros, Agape and Philia: Readings in the Philosophy of Love.'' St. Paul, MN: Paragon House Publishers, 1999. ISBN 9781557782786 | ||

| + | * Vacek, Edward Collins. ''Love, Human and Divine: The Heart of Christian Ethics (Moral Traditions).'' Georgetown University Press; New Ed edition, 1996. ISBN 9780878406272 | ||

| + | * Whitehead, Alfred North. ''Adventures of Ideas.'' Cambridge University Press, 1933. | ||

| + | * Williams, Daniel Day. ''God's Grace and Man's Hope: An Interpretation of the Christian Life in History.'' Harper & Row, 1965. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Category: Religion]] | |

| − | + | [[category: Philosophy and religion]] | |

| − | |||

| − | + | {{credits|Agape|158986571|Greek_words_for_love|160515374}} | |

| − | |||

| − | {{ | ||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 15:57, 7 February 2019

Agapē (αγάπη in Greek) is one of several Greek words translated into English as love. Greek writers at the time of Plato and other ancient authors used forms of the word to denote love of a spouse or family, or affection for a particular activity, in contrast to, if not with a totally separate meaning from, philia (an affection that could denote either brotherhood or generally non-sexual affection) and eros (an affection of a sexual nature, usually between two unequal partners, although Plato's notion of eros as love for beauty is not necessarily sexual). The term agape with that meaning was rarely used in ancient manuscripts, but quite extensively used in the Septuagint, the Koine Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible.

In the New Testament, however, agape was frequently used to mean something more distinctive: the unconditional, self-sacrificing, and volitional love of God for humans through Jesus, which they ought also to reciprocate by practicing agape love towards God and among themselves. The term agape has been expounded on by many Christian writers in a specifically Christian context. In early Christianity, agape also signified a type of eucharistic feast shared by members of the community.

The Latin translation of agape in the Vulgate is usually caritas, which in older Bibles is sometimes translated "charity." St. Augustine believed caritas to contain not only agape but also eros, because he thought it includes the human desire to be like God. The Swedish Lutheran theologian Anders Nygren critiqued the Augustinian theory, sharply distinguishing between agape (unmotivated by the object) and eros (motivated and evoked by the object) and regarding agape as the only purely Christian kind of love. Yet Nygren's theory has been criticized as having an excessively narrow understanding of agape that is unable to appreciate the relational nature of divine love, as it is often so portrayed in the Bible.

Greek Words for Love

Ancient Greek distinguishes a number of words for love, of which three are most prominent: eros, philia, and agape. As with other languages, it has been historically difficult to separate the meanings of these words totally. However, the senses in which these words were generally used are given below:

- Eros (ἔρως érōs) is passionate love and attraction including sensual desire and longing. It is love more intimate than the philia love of friendship. The modern Greek word "erotas" means "romantic love," and the ancient Greek word eros, too, applies to dating relationships and marriage. The word eros with the meaning of sexual love appears one time (Proverbs 7:18) in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, but it is absent in the Koine Greek text of the New Testament. Eros in ancient Greek is not always sexual in nature, however. For Plato, while eros is initially felt for a person, with contemplation it becomes an appreciation of the beauty within that person, or even an appreciation of beauty itself. It should be noted that Plato does not talk of physical attraction as a necessary part of love, hence the use of the word platonic to mean, "without physical attraction." The most famous ancient work on the subject of eros is Plato's Symposium, which is a discussion among the students of Socrates on the nature of eros.[1] Plato says eros helps the soul recall knowledge of beauty, and contributes to an understanding of spiritual truth. Lovers and philosophers are all inspired to seek truth by eros.

- Philia (φιλία philía) means friendship and dispassionate virtuous love. It includes loyalty to friends, family, and community, and requires virtue, equality and familiarity. In ancient texts, philia denotes a general type of love, used for love between friends, and family members, as well as between lovers. This, in its verb or adjective form (i.e., phileo or philos), is the only other word for "love" used in the New Testament besides agape, but even then it is used substantially less frequently.

- Agape (ἀγάπη agápē) refers to a general affection of "love" rather than the attraction suggested by eros; it is used in ancient texts to denote feelings for a good meal, one's children, and one's spouse. It can be described as the feeling of being content or holding one in high regard. This broad meaning of agape or its verb agapao can be seen extensively in the Septuagint as the Greek translation of the common Hebrew term for love (aḥaba), which denotes not only God's love for humanity but also one's affection for one's spouse and children, brotherly love, and even sexual desire. It is uncertain why agape was chosen, but the similarity of consonant sounds (aḥaba) may have played a part. This usage provides the context for the choice of this otherwise still quite obscure word, in preference to other more common Greek words, as the most frequently used word for love in the New Testament. But, when it is used in the New Testament, its meaning becomes more focused, mainly referring to unconditional, self-sacrificing, giving love to all—both friend and enemy.

Additionally, modern Greek contains two other words for love:

- Storge (στοργή storgē) means "affection"; it is natural affection, like that felt by parents for offspring. The word was rarely used in ancient works, and almost exclusively as a descriptor of relationships within the family.

- Thelema (θέλημα) means "desire"; it is the desire to do something, to be occupied, to be in prominence.

Agape in Christianity

New Testament

In the New Testament, the word agape or its verb form agapao appears more than 200 times. It is used to describe:

- God's love for human beings: "God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son (John 3:16); "God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us (Romans 5:8); "God is love" (1 John 4:8).

- Jesus' love for human beings: "Christ loved us and gave himself up for us as a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God (Ephesians 5:2).

- What our love for God should be like: "Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind" (Matthew 22:37).

- What our love for one another as human beings should be like: "Love your neighbor as yourself" (Matthew 22:39); "Love each other as I have loved you" (John 15:12); "Love does no harm to its neighbor. Therefore love is the fulfillment of the law" (Romans 13:10).

Agape in the New Testament is a form of love that is voluntarily self-sacrificial and gratuitous, and its origin is God. Its character is best described in the following two passages:

Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you. If someone strikes you on one cheek, turn to him the other also. If someone takes your cloak, do not stop him from taking your tunic. Give to everyone who asks you, and if anyone takes what belongs to you, do not demand it back. Do to others as you would have them do to you. If you love those who love you, what credit is that to you? Even 'sinners' love those who love them. And if you do good to those who are good to you, what credit is that to you? Even 'sinners' do that. And if you lend to those from whom you expect repayment, what credit is that to you? Even 'sinners' lend to 'sinners,' expecting to be repaid in full. But love your enemies, do good to them, and lend to them without expecting to get anything back. Then your reward will be great, and you will be sons of the Most High, because he is kind to the ungrateful and wicked. Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful (Luke 6:27-36).

If I speak in the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal. If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have a faith that can move mountains, but have not love, I am nothing. If I give all I possess to the poor and surrender my body to the flames, but have not love, I gain nothing. Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It is not rude, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres (1 Corinthians 13:1-7).

However, the verb agapao is at times used also in a negative sense, where it retains its more general meaning of "affection" rather than unconditional love or divine love. Such examples include: "for Demas, because he loved (agapao) this world, has deserted me and has gone to Thessalonica (2 Timothy 4:10); "for they loved (agapao) praise from men more than praise from God (John 12:43); and "Light has come into the world, but men loved (agapao) darkness instead of light because their deeds were evil (John 3:19).

Agape as a meal

The word agape in its plural form is used in the New Testament to describe a meal or feast eaten by early Christians, as in Jude 1:12, 2 Peter 2:13, and 1 Corinthians 11:17-34. The agape meal was either related to the Eucharist or another term used for the Eucharist.[2] It eventually fell into disuse.

Later Christian development

Because of the frequent use of the word agape in the New Testament, Christian writers have developed a significant amount of theology based solely on the interpretation of it.

The Latin translation of agape is usually caritas in the Vulgate and amongst Catholic theologians such as St. Augustine. Hence the original meaning of "charity" in English. The King James Version uses "charity" as well as "love" to translate the idea of agape or caritas. When Augustine used the word caritas, however, he meant by it more than self-sacrificial and gratuitous love because he included in it also the human desire to be like God in a Platonic way. For him, therefore, caritas is neither purely agape nor purely eros but a synthesis of both.

The twentieth-century Swedish Lutheran theologian Anders Nygren made a sharp distinction between agape and eros, saying that the former indicates God's unmerited descent to humans, whereas the latter shows humans' ascent to God. According to Nygren, agape and eros have nothing to do with each other, belonging to two entirely separate realms. The former is divine love that creates and bestows value even on the unlovable object, whereas the latter is pagan love that seeks its own fulfillment from any value in the object. The former, being altruistic, is the center of Christianity, whereas the latter is egocentric and non-Christian. Based on this, Nygren critiqued Augustine's notion of caritas, arguing that it is an illegitimate synthesis of eros and agape, distorting the pure, Christian love that is agape. Again, according to Nygren, agape is spontaneous, unmotivated by the value of (or its absence in) the object, creative of value in the object, and initiative of God's fellowship, whereas eros is motivated and evoked by the quality, value, beauty, or worth of the object. Nygren's observation is that agape in its pure form was rehabilitated through Martin Luther's Protestant Reformation.[3]

In 2006, Pope Benedict XVI in his first encyclical, Deus Caritas Est, addressed this issue, saying that eros and agape are both inherently good as two separable halves of complete love that is caritas, although eros may risk degrading to mere sex without a spiritual support. It means that complete love involves the dynamism between the love of giving and the love of receiving.[4]

Criticisms of Nygren

Nygren's sharp distinction of agape and eros has been criticized by many. Daniel Day Williams, for example, has critiqued Nygren, referring to the New Testament passage: "Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled" (Matthew 5:6). This passage, according to Williams, shows that the two types of love are related to each other in that God's agape can be given to those who strive for righteousness in their love of eros for it, and that Nygren's contrasting categorizations of agape as absolutely unconditional and of eros as an egocentric desire for fellowship with God do not work.[5] How can our desire for fellowship with God be so egocentric as not to be able to deserve God's grace?

Another way of relating agape to eros has been suggested by process theologians. According to them, the ultimate purpose of agape is to help create value in the object so that the subject may be able to eventually appreciate and enjoy it through eros. When God decides to unconditionally love us in his attempt to save us, doesn't he at the same time seek to see our salvation eventually? This aspect of God's love which seeks the value of beauty in the world is called "Eros" by Alfred North Whitehead, who defines it as "the living urge towards all possibilities, claiming the goodness of their realization."[6] One significant corollary in this more comprehensive understanding of love is that when the object somehow fails to build value in response, the subject suffers. Hence, process theologians talk about the suffering of God, and argue that it is an important biblical theme especially in the Hebrew Bible that records that God suffered as a "God in Search of Man"—a phrase which is the title of a book written by the Jewish theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel.[7]

It seems, therefore, that agape and eros, while distinguishable from each other, are closely connected. Love, as understood this way, applies not only to the mutual relationship between God and humans but also to the reciprocal relationship among humans. It can be recalled that ancient Greek did not share the modern tendency to sharply differentiate between the various terms for love such as agape and eros.

Notes

- ↑ Plato, The Symposium, tr. Christopher Gill (Penguin Classics, 2003).

- ↑ J. F. Keating. The Agape and the Eucharist in the Early Church: Studies in the History of the Christian Love-Feasts. (Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007).

- ↑ Anders Nygren. Agape and Eros (Westminster Press, 1953).

- ↑ Deus Caritas Est..Vatican Library. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

- ↑ Daniel Day Williams. God's Grace and Man's Hope: An Interpretation of the Christian Life in History. (Harper & Row, 1965).

- ↑ Alfred North Whitehead. Adventures of Ideas. (Cambridge University Press, 1933), 381.

- ↑ Abraham Joshua Heschel. God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism. (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Heschel, Abraham Joshua. God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976. ISBN 0374513317

- Keating, J. F. The Agape and the Eucharist in the Early Church: Studies in the History of the Christian Love-Feasts. Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007. ISBN 9780548287699

- Lewis, C. S. The Four Loves. Fount, 2002. ISBN 0006280897

- Nygren, Anders. Agape and Eros. Westminster Press, 1953.

- Outka, Gene. Agape: An Ethical Analysis (Yale Publications in Religion). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977. ISBN 9780300021226

- Plato. The Symposium, Translated by Christopher Gill. Penguin Classics, 2003. ISBN 9780140449273

- Soble, Alan. Eros, Agape and Philia: Readings in the Philosophy of Love. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House Publishers, 1999. ISBN 9781557782786

- Vacek, Edward Collins. Love, Human and Divine: The Heart of Christian Ethics (Moral Traditions). Georgetown University Press; New Ed edition, 1996. ISBN 9780878406272

- Whitehead, Alfred North. Adventures of Ideas. Cambridge University Press, 1933.

- Williams, Daniel Day. God's Grace and Man's Hope: An Interpretation of the Christian Life in History. Harper & Row, 1965.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.