Tinnitus

| Tinnitus Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | H93.1 |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 388.3 |

| DiseasesDB | 27662 |

| MedlinePlus | 003043 |

| eMedicine | ent/235 |

| MeSH | D014012 |

Tinnitus is the perception of sound in one or both ears or in the head in general in the absence of a corresponding external stimulus. It may appear as a buzzing, ringing, whistling, clicking, or other noise, even music. It is sometimes referred to as "ringing in the ears." Tinnitus, which may correctly be pronounced as either ti-NIGHT-us or TIN-i-tus[1] can be defined as either objective tinnitus or subjective tinnitus [2][3] Objective tinnitus is a condition where the doctor can also hear the sound, such as caused by turbulent blood flow through malformed vessels or rhythmic muscular spasms.[2] Most cases of tinnitus is subjective tinnitus, which means only the person can hear the sounds.[1]

Almost everyone experiences a transient or mild form of tinnitus, but around ten to fourteen percent of adults complain of tinnitus that is prolonged or present much of the time, and 0.5 percent are affected so strongly as to have difficulty leading a normal life.[4]

Tinnitus is a symptom, not a disease, involving an underlying cause and the disruption of the normal harmony of the human body.

The word tinnitus comes from Latin, meaning "to tinkle or to ring like a bell."[1]

Overview

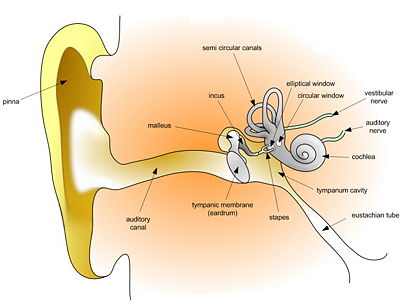

In addition to sounds external to the body, there are many sounds generated within the head of a person as a result of muscle activity or blood flowing through the cranial vessels.[4] However, the cochlea of the ear is shielded by a hard, temporal bone and thus we are rarely aware of these sounds.[4]

Tinnitus involves the hearing of sounds that are not external to the body, with the perception in one or both ears or in the head. It is usually described as a ringing noise, but in some patients it takes the form of a high pitched whining, buzzing, hissing, humming, or whistling sound, or as ticking, clicking, roaring, "crickets" or "locusts," tunes, songs, or beeping.[5] It has also been described as a "whooshing" sound, as of wind or waves.[6]

Tinnitus is not itself a disease but a symptom resulting from a range of underlying causes, including ear infections, foreign objects or wax in the ear, and injury from loud noises. Tinnitus is also a side-effect of some oral medications, such as aspirin, and may also result from an abnormally low level of serotonin activity.

The sound perceived may range from a quiet background noise to one that can be heard even over loud external sounds. The term "tinnitus" usually refers to more severe cases. A 1953 research report on a study of 80 tinnitus-free university students placed in an anechoic chamber (a room without echoes) found that 93 percent reported hearing a buzzing, pulsing, or whistling sound. Cohort studies have demonstrated that damage to hearing (among other health effects) from unnatural levels of noise exposure is very widespread in industrialized countries.[7]

Because tinnitus is often defined as a subjective phenomenon, it is difficult to measure using objective tests, such as by comparison to noise of known frequency and intensity, as in an audiometric test. The condition is often rated clinically on a simple scale from "slight" to "catastrophic" according to the practical difficulties it imposes, such as interference with sleep, quiet activities, or normal daily activities.[8] For research purposes, the more elaborate Tinnitus Handicap Inventory is often used.[9][10]

Objective tinnitus

In a minority of cases, a clinician can perceive an actual sound (e.g., a bruit) emanating from the patient's ears. This is called objective tinnitus. Objective tinnitus can arise from muscle spasms that cause clicks or crackling around the middle ear.[11]

Some people experience a sound that beats in time with the pulse (pulsatile tinnitus.[12]) Pulsatile tinnitus is usually objective in nature, resulting from altered blood flow or increased blood turbulence near the ear (such as from atherosclerosis or venous hum[13]), but it can also arise as a subjective phenomenon from an increased awareness of blood flow in the ear.[12] Rarely, pulsatile tinnitus may be a symptom of potentially life-threatening conditions such as carotid artery aneurysm[14] or carotid artery dissection.[15]

Measuring tinnitus

The basis of quantitative measurement of tinnitus relies on the brain’s tendency to select out only the loudest sounds heard. Based on this tendency, the amplitude of a patient's tinnitus can be measured by playing sample sounds of known amplitude and asking the patient which he or she hears. The tinnitus will be equal to or less than sample noises heard by the patient. This method works very well to gauge objective tinnitus (see above.) For example: If a patient has a pulsatile paraganglioma in his ear, he will not be able to hear the blood flow through the tumor when the sample noise is five decibels louder than the noise produced by the blood. As sound amplitude is gradually decreased, the tinnitus will become audible, and the level at which it does so provides an estimate of the amplitude of the objective tinnitus.

Objective tinnitus, however, is quite uncommon. Often patients with pulsatile tumors will report other coexistent sounds, distinct from the pulsatile noise, that will persist even after their tumor has been removed. This is generally subjective tinnitus, which, unlike the objective form, cannot be tested by comparative methods.

If a subject is focused on a sample noise, they can often detect it to levels below five decibels, which would indicate that their tinnitus would be almost impossible to hear. Conversely, if the same test subject is told to focus only on their tinnitus, they will report hearing the sound even when test noises exceed 70 decibels, making the tinnitus louder than a ringing phone. This quantification method suggests that subjective tinnitus relates only to what the patient is attempting to hear. Patients actively complaining about tinnitus could thus be assumed to be people who have become obsessed with the noise. This is only partially true. The problem is involuntary; generally complaining patients simply cannot override or ignore their tinnitus. The noise is often present in both quiet and noisy environments, and can become quite intrusive to their daily lives.

Subjective tinnitus may not always be correlated with ear malfunction or hearing loss. Even people with near-perfect hearing may still complain of it. Tinnitus may also have a connection to memory problems, anxiety, fatigue, or a general state of poor health.

Mechanisms of subjective tinnitus

One of the possible mechanisms relies in the otoacoustic emissions. The inner ear contains thousands of minute hairs that vibrate in response to sound waves and cells that convert neural signals back into acoustical vibrations. The sensing cells are connected with the vibratory cells through a neural feedback loop, whose gain is regulated by the brain. This loop is normally adjusted just below onset of self-oscillation, which gains the ear spectacular sensitivity and selectivity. If something changes, it is easy for the delicate adjustment to cross the barrier of oscillation and tinnitus results. This can actually be measured by a very sensitive microphone outside the ear.

Other possible mechanisms of how things can change in the ear is damage to the receptor cells. Although receptor cells can be regenerated from the adjacent supporting Deiters cells after injury in birds, reptiles, and amphibians, in mammals it is believed that they can be produced only during embryogenesis. Although mammalian Deiters cells reproduce and position themselves appropriately for regeneration, they have not been observed to transdifferentiate into receptor cells except in tissue culture experiments.[16][17] Therefore, if these hairs become damaged, through prolonged exposure to excessive decibel levels, for instance, then deafness to certain frequencies occurs. In tinnitus, they may falsely relay information at a certain frequency that an externally audible sound is present, when it is not.

The mechanisms of subjective tinnitus are often obscure. While it is not surprising that direct trauma to the inner ear can cause tinnitus, other apparent causes (e.g., temporomandibular joint disorder (TMJ) and dental disorders) are difficult to explain. Recent research has proposed that there are two distinct categories of subjective tinnitus: otic tinnitus, caused by disorders of the inner ear or the acoustic nerve, and somatic tinnitus, caused by disorders outside the ear and nerve but still within the head or neck. It is further hypothesized that somatic tinnitus may be due to "central crosstalk" within the brain, as certain head and neck nerves enter the brain near regions known to be involved in hearing.

While most discussions of tinnitus tend to stress physical mechanisms, there is strong evidence that the level of an individual's awareness of their tinnitus can be stress-related, and so should be addressed by improving the state of the nervous system generally, using gradual, unobtrusive, long-term treatments[18]

Prevention

Tinnitus and hearing loss can be permanent conditions, thus, precautionary measures are advisable. If a ringing in the ears is audible after exposure to a loud environment, such as a rock concert or a work place, it means that damage has been done. Prolonged exposure to noise levels as low as 70 dB can result in damage to hearing. If it is not possible to limit exposure, earplugs or ear defenders should be worn. For musicians and DJs, special musician's earplugs can lower the volume of the music without distorting the sound and can prevent tinnitus from developing in later years.

It is also important to check medications for potential ototoxicity. Ototoxicity can be cumulative between medications, or can greatly increase the damage done by noise. If ototoxic medications must be administered, close attention by the physician to prescription details, such as dose and dosage interval, can reduce the damage done.[19]

Causes of subjective tinnitus

Tinnitus can have many different causes, but most commonly results from otologic disorders—the same conditions that cause hearing loss. The most common cause is noise-induced hearing loss, resulting from exposure to excessive or loud noises. Ototoxic drugs can cause tinnitus either secondary to hearing loss or without hearing loss, and may increase the damage done by exposure to loud noise, even at doses that are not in themselves ototoxic.[20]

Causes of tinnitus include:[21]

- Otologic problems and hearing loss:

- conductive hearing loss

- external ear infection

- acoustic Shock

- cerumen (earwax) impaction

- middle ear effusion

- sensorineural hearing loss

- excessive or loud noise

- presbycusis (age-associated hearing loss)

- Ménière's disease

- acoustic neuroma

- mercury or lead poisoning

- ototoxic medications

- analgesics:

- aspirin

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- antibiotics:

- aminoglycosides e.g. gentamicin

- chloramphenicol

- erythromycin

- tetracycline

- vancomycin

- chemotherapy and antiviral drugs:

- bleomycin

- interferon

- pegylated interferon-alpha-2b

- cisplatin

- mechlorethamine

- methotrexate

- vincristine

- loop diuretics:

- bumetanide

- ethacrynic acid

- furosemide

- others:

- chloroquine

- quinine

- analgesics:

- Psychedelic drugs:

- Diisopropyltryptamine (DiPT)

- 5-Methoxy-diisopropyltryptamine

- conductive hearing loss

- neurologic disorders:

- chiari malformation

- multiple sclerosis

- head injury

- skull fracture

- closed head injury

- whiplash injury

- temporomandibular joint disorder

- metabolic disorders:

- thyroid disorder

- hyperlipidemia

- vitamin B12 deficiency

- psychiatric disorders:

- other causes:

- Tension Myositis Syndrome

- fibromyalgia

- hypertonia (Muscle Tension)

- thoracic outlet syndrome

- lyme disease

- hypnogogia

- sleep paralysis

Treatment

There are many treatments that are effective for objective tinnitus. But there are no clear effective treatments for subjective tinnitus. Conversely, tinnitus may resolve without any treatment. In subjective tinnitus, treatment of associated problems like fatigue, anxiety, and poor health is sometimes helpful. Effective treatments include:

Objective tinnitus:

- Gamma knife radiosurgery (glomus jugulare)[22]

- Shielding of cochlea by teflon implant[23]

- Botulinum toxin (palatal tremor)[24]

- Propranolol and clonazepam (arterial anatomic variation)[25]

Subjective tinnitus:

- Drugs and nutrients

- Lidocaine, injection into the inner ear found to suppress the tinnitus for 20 minutes, according to a Swedish study. [26]

- Benzodiazepines (xanax, ativan, klonopin)

- Avoidance of caffeine, nicotine, salt[27][28][29]

- Avoidance of or consumption of alcohol[30][29]

- Zinc supplementation (where serum zinc deficiency is present)[31][32][33]

- Acamprosate[34]

- Etidronate or sodium fluoride (otosclerosis)[35]

- Lignocaine or anticonvulsants (usually in patients responsive to white noise masking)[36]

- Carbemazepine[37]

- Melatonin (especially for those with sleep disturbance)[38]

- Sertraline[39]

- Vitamin combinations (Lipoflavonoid)[40]

- Electrical stimulation

- Surgery

- Repair of perilymph fistula[45]

- External sound

- Low-pitched sound treatment has shown some positive, encouraging results.[46]

- Tinnitus masking[47] (white noise)

- Tinnitus retraining therapy[48][49]

- Auditive stimulation therapy (music therapy)[50]

- Compensation for lost frequencies by use of a hearing aid.[51]

- Ultrasonic bone-conduction external acoustic stimulation[52][53]

- Avoidance of outside noise (exogenous tinnitus)[54]

- Psychological

- Cognitive behavior therapy[55]

- Light-based

- Photobiomodulation (a.k.a. Low Level Laser Therapy); efficacy is debated[56]

Although there are no specific cures for tinnitus, anything that brings the person out of the "fight or flight" stress response helps symptoms recede over a period of time. Calming body-based therapies, counseling, and psychotherapy help restore well-being, which in turn allows tinnitus to settle. Chronic tinnitus can be quite stressful psychologically, as it distracts the affected individual from mental tasks and interferes with sleep, particularly when there is no external sound. Additional steps in reducing the impact of tinnitus on adverse health consequences include: a review of medications that may have tinnitus as a side effect; a physical exam to reveal possible underlying health conditions that may aggravate tinnitus; receiving adequate rest each day; and seeking a physician's advice concerning a sleep aid to allow for a better sleep pattern.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 American Tinnitus Association (ATA), "About tinnitus,", American Tinnitus Association. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 R. J. Frey, "Tinnitus," in J. L. Longe, The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine (Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2006). ISBN 1414403682

- ↑ P. Ford-Martin and R. J. Frey, "Tinnitus," in J. L. Longe, ''The Gale Encyclopedia of Alternative Medicine (Farmington Hills, Mich: Thomson/Gale. 2005). ISBN 0787693960.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 A. J. King, "Tinnitus," in C. Blakemore and S. Jennett, The Oxford Companion to the Body (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001). ISBN 019852403X

- ↑ Royal National Institute for Deaf People (RNID), "What is tinnitus" RNID. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ National Institutes of Health and National Library of Medicine, "Tinnitus," Medline Plus (2007). Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ K. M. Holgers and B. Pettersson, "Noise exposure and subjective hearing symptoms among school children in Sweden," Noise Health 27(2005): 27-27. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ McCombe, A., "Guidelines for the grading of tinnitus severity: The results of a working group commissioned by the British Association of Otolaryngologists, Head and Neck Surgeons," Otohns.net (1999). Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ MedicDirect, "Tinnitus handicap inventory," MedicDirect (2006). Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ C. W. Newman, G. P. Jacobson, and J. B. Spitzer, "Development of the tinnitus handicap inventory," Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 122(1996)(2): 143-148.

- ↑ American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS), "Tinnitus," American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) (2007). Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Royal National Institute for Deaf People (RNID), "Pulsatile tinnitus," RNID. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ J. R. Chandler, "Diagnosis and cure of venous hum tinnitus," Laryngoscope 93(1983)(7): 892-895

- ↑ G. Moonis, C. J. Hwang, T. Ahmed, J. B. Weigele, and R. W. Hurst, "Otologic manifestations of petrous carotid aneurysms," AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 26(2005)(6): 1324-1327.

- ↑ M. Selim and L. R. Caplan, "Carotid artery dissection," Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med.6(2004)(3): 249-253.

- ↑ T. Yamasoba and K. Kondo, "Supporting cell proliferation after hair cell injury in mature guinea pig cochlea in vivo," Cell Tissue Res. 325(2006)(1):23-31.

- ↑ P. M. White, A. Doetzlhofer, Y. S. Lee, A. K. Groves, and N. Segil, "Mammalian cochlear supporting cells can divide and trans-differentiate into hair cells," Nature 441(2006)(7096): 984-987.

- ↑ .Paralumun, "Tinnitus," Paralumum (no date). Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ V. P. García, F. A. Martínez, E. B. Agustí, L. A. Mencía, and V. P. Asenjo, "Drug-induced otoxicity: Current status," Acta Oto-Laryngologica 121(2001)(5): 569-572.

- ↑ R. D. Brown, J. E. Penny, C. M. Henley, K. B. Hodges, S. A. Kupetz, D. W. Glenn, and J. C. Jobe, "Ototoxic drugs and noise," Ciba Found Symp. 85(1981): 151-171.

- ↑ R. W. Crummer and G. A. Hassan, "Diagnostic approach to tinnitus," Am Fam Physician 69(2004)(1): 120-126.

- ↑ S. N. Willen, D. B. Einstein , R. J. Maciunas, and C. A. Megerian, "Treatment of glomus jugulare tumors in patients with advanced age: Planned limited surgical resection followed by staged gamma knife radiosurgery: A preliminary report," Otol Neurotol. 26(2005)(6): 1229-1234. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ D. De Ridder, L. De Ridder, V. Nowé, H. Thierens, P. Van de Heyning, and A. Møller, "Pulsatile tinnitus and the intrameatal vascular loop: Why do we not hear our carotids?" Neurosurgery 57(2005)(6): 1213-1217. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ S. E. Penney, I. A. Bruce, and S. R. Saeed, "Botulinum toxin is effective and safe for palatal tremor: A report of five cases and a review of the literature," J Neurol. 253(2006)(7): 857-860. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ S. Albertino, A. R. Assunção, and J. A. Souza, "Pulsatile tinnitus: Treatment with clonazepam and propranolol," Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol (Engl Ed). 71(2005)(1): 111-113. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ Lake Medels Varlden, Swedish website about tinnitus, Lakemedelsvarlden.nu. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ Rogers, J. Only When I Eat: Tinnitus Hope at Last. (London : Regency, 1984).

- ↑ W. L. Meyerhoff and B. E. Mickey, "Vascular decompression of the cochlear nerve in tinnitus sufferers," Laryngoscope 98(1988)(6 Pt 1): 602-604. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 G. W. Knox and A. McPherson, "Meniere's disease: Differential diagnosis and treatment," Am Fam Physician 55(1997)(4): 1185-1190, 1193-4. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ R. Pugh, R. J. Budd, and S. D. Stephens, "Patients' reports of the effect of alcohol on tinnitus," Br J Audiol. 29(1995)(5): 279-283. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ H. N. Arda, U. Tuncel, O. Akdogan, and L. N. Ozluoglu, "The role of zinc in the treatment of tinnitus," Otol Neurotol. 24(2003)(1): 86-89. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ S. Yetiser, F. Tosun, B. Satar, M. Arslanhan, T. Akcam, and Y. Ozkaptan, "The role of zinc in management of tinnitus," Auris Nasus Larynx. 29(2002)(4): 329-333. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ P. B. Paaske, C. B. Pedersen, G. Kjems, and I. L. Sam, "Zinc in the management of tinnitus. Placebo-controlled trial," Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 100(1991)(8): 647-649. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ A. A. Azevedo and R. R. Figueiredo, "Tinnitus treatment with acamprosate: Double-blind study," Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol (Engl Ed). 71(2005)(5): 618-623. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ K. H. Brookler and H. Tanyeri, "Etidronate for the the neurotologic symptoms of otosclerosis: preliminary study," Ear Nose Throat J. 76(1997)(6): 371-376, 379-81. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ R. J. Goodey, "Drugs in the treatment of tinnitus," Ciba Found Symp. 85(1981): 263-278. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ R. A. Levine, "Typewriter tinnitus: a carbamazepine-responsive syndrome related to auditory nerve vascular compression," ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 68(2006)(1): 43-46. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ U. C. Megwalu, J. E. Finnell, J. F. Piccirillo, "The effects of melatonin on tinnitus and sleep," Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 134(2006)(2): 210-213. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ S. Zöger, J. Svedlund, and K. M. Holgers, "The effects of sertraline on severe tinnitus suffering—a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study," J Clin Psychopharmacol. 26(2006)(1): 32-39. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ H. L. Williams, F. T. Maher, K. B. Corbin, et al., Eriodictyol glycoside in the treatment of Meniere’s disease. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 72(1963): 1082.

- ↑ B. Langguth, M. Zowe, M. Landgrebe, P. Sand, T. Kleinjung, H. Binder, G. Hajak, and P. Eichhammer "Transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of tinnitus: a new coil positioning method and first results," Brain Topogr. 18(2006)(4): 241-247. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ F. Fregni, R. Marcondes, P. S. Boggio, M. A. Marcolin, S. P. Rigonatti, T. G. Sanchez, M. A. Nitsche, and A. Pascual-Leone, "Transient tinnitus suppression induced by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct current stimulation," Eur J Neurol. 13(2006)(9): 996-1001. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ G. Aydemir, M. S. Tezer, P. Borman, H. Bodur, and A. Unal, "Treatment of tinnitus with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation improves patients' quality of life," J Laryngol Otol. 120(2006)(6): 442-445. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ D. De Ridder, G. De Mulder, E. Verstraeten, K. Van der Kelen, S. Sunaert, M. Smits, S. Kovacs, J. Verlooy, P. Van de Heyning, and A. R. Moller, "Primary and secondary auditory cortex stimulation for intractable tinnitus," ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 68(2006)(1): 48-54. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ F. Goto, K. Ogawa, T. Kunihiro, K. Kurashima, H. Kobayashi, and J. Kanzaki, "Perilymph fistula—45 case analysis," Auris Nasus Larynx. 28(2001)(1): 29-33. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ University of California at Irving, "Low-pitch treatment alleviates ringing sound of tinnitus," UC, Irvine press release Feb. 14, 2007. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ Chu, S., "Tinnitus masker: Sonic designs by Jon Dattorro," Stanford University. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ C. Herraiz, F. J. Hernandez, G. Plaza, and G. de los Santos, "Long-term clinical trial of tinnitus retraining therapy," Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 133(2005)(5): 774-779. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ J. A. Henry, M. A. Schechter, T. L. Zaugg, S. Griest, P. J. Jastreboff, J. A. Vernont, C. Kaelin, M. B. Meikle, K. S. Lyons, and B. J. Stewart, "Outcomes of clinical trial: tinnitus masking versus tinnitus retraining therapy," J Am Acad Audiol. 17(2006)(2): 104-132. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ M. Kusatz, T. Ostermann, and D. Aldridge, "Auditive stimulation therapy as an intervention in subacute and chronic tinnitus: a prospective observational study," Int Tinnitus J. 11(2005)(2): 163-169. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ OHSU Tinnitus Cliniic, "Comprehensive treatment programs including tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT)," OHSU Tinnitus Clinic (2006). Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ B. A. Goldstein, A. Shulman, and M. L. Lenhardt, "Ultra-high-frequency ultrasonic external acoustic stimulation for tinnitus relief: a method for patient selection," Int Tinnitus J. 11(2005)(2): 111-114. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ B. A. Goldstein, M. L. Lenhardt, and A. Shulman, "Tinnitus improvement with ultra-high-frequency vibration therapy," Int Tinnitus J. 11(2005)(1): 14-22. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ C. F. Claussen, "Subdividing tinnitus into bruits and endogenous, exogenous, and other forms," Int Tinnitus J. 11(205)(2): 126-136. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ G. Andersson, D. Porsaeus, M. Wiklund, v. Kaldo, and H. C. Larsen, "Treatment of tinnitus in the elderly: a controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy," Int J Audiol. 44(2005)(11): 671-675. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ↑ B. Keate, "Low level laser therapy for tinnitus," TinnitusForumula.com. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hogan, K. Tinnitus: Turning the Volume Down. Proven Strategies for Quieting the Moise in Your Head. Eagan, MN: Network 3000 Pub., 2003. ISBN 097093212X.

| |||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.