Saccharin

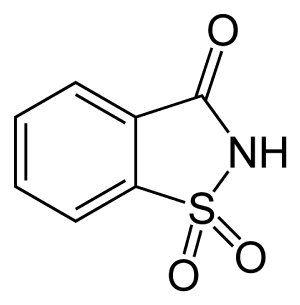

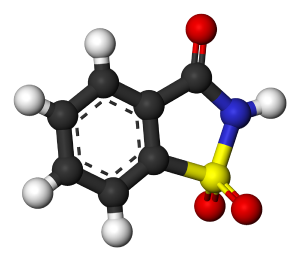

Saccharin is a synthetic organic compound that tastes hundreds of times sweeter than cane sugar (sucrose) and is used as a calorie-free sweetener. Discovered in 1879, it is the oldest known commercial artificial sweetener. Saccharin lacks nutritional value for the body. It has the chemical formula C7H5NO3S.

Pure saccharin is not soluble in water, but if the molecule is combined with sodium or calcium as a salt the salt is very soluble. Saccharin salt formed with sodium, and to a lesser extent with calcium, is used as a sweetener in foods and beverages and as a flavoring agent in toothpaste, pharmaceuticals, and other items. Various accounts place saccharin between 200 and 700 times sweeter than sucrose. It is excreted unchanged by the body.

Human beings have an attraction to sweet items: desserts, fruits, honey, and so forth, which stimulate the sense of taste. However, sweet things tend to have a lot of calories, thus contributing to problems with obesity. Furthermore, those with diabetes must severely limit their consumption of sugar in order to maintain their blood glucose levels within acceptable limits. Saccharin provides the desired sweetness without high calories and other physical characteristics of sugar traced to deleterious health consequences.

As the first artificial sweetener, saccharin was eagerly received as a new chemical that diabetics and dieters can utilize. Also as the first artificial sweetener, saccharin provides an example of the way in which the application of human creativity can lead to positive or negative consequences or both, and can be achieved through either ethical or unethical practices. While production of an artificial sweetener offers significant potential for health benefits, it also was alleged by official government warnings for nearly two decades that saccharin is a potential carcinogen. Although saccharin was jointly discovered by two researchers working together, one went on to patent and mass-produce it without ever mentioning the other, growing wealthy in the process.

Chemistry and characteristics

Saccharin has the chemical formula C7H5NO3S. It can be produced in various ways (Ager et al. 1998). The original route, utilized by the discoverers Remsen and Fahlberg, starts with toluene, but yields from this starting point are small. In 1950, an improved synthesis was developed at the Maumee Chemical Company of Toledo, Ohio. In this synthesis, anthranilic acid successively reacts with nitrous acid, sulfur dioxide, chlorine, and then ammonia to yield saccharin. Another route begins with o-chlorotoluene (Bungard 1967).

In its acidic form, saccharin is not particularly water-soluble. The form used as an artificial sweetener is usually its sodium salt, which has the chemical formula C7H4NNaO3S·2H2O. The calcium salt is also sometimes used, especially by people restricting their dietary sodium intake. While pure saccharin is insoluble in water, both salts are highly water-soluble yielding 0.67 grams (0.02 ounces) of saccharin per milliliter (0.2 teaspoons) of water at room temperature.

Sodium saccharin is about 300 to 500 times as sweet tasting as sucrose, but has an unpleasant bitter or metallic aftertaste, especially at high concentrations.

Saccharin was an important discovery, especially for diabetics. Saccharin goes directly through the human digestive system without being digested. It does not affect blood insulin levels, and has effectively no food energy.

Unlike the newer artificial sweetener aspartame, saccharin is stable when heated, even in the presence of acids. It also does not react chemically with other food ingredients, and stores well. Blends of saccharin with other sweeteners are often used to compensate for each sweetener's weaknesses. A 10:1 cyclamate:saccharin blend is common in countries where both these sweeteners are legal; in this blend, each sweetener masks the other's off-taste. Like saccharin, cyclamate, which is another artificial sweetener, is stable when heated. Saccharin is roughly 10 times sweeter than cyclamate, while cyclamate is less costly to produce than saccharin. In diet fountain beverages, Saccharin is often used together with aspartame so that some sweetness remains should the fountain syrup be stored beyond aspartame's relatively short shelf life.

History

Saccharin is the oldest commercial artificial sweetener, its sweetness having been discovered in 1879 by Ira Remsen, a professor at Johns Hopkins University, and Constantine Fahlberg, a research fellow working in Remsen's lab. While working with coal tar derivatives (toluene), Remsen discovered saccharin's sweetness at dinner after not thoroughly washing his hands, as did Fahlberg during lunch. Remsen and Fahlberg jointly published their discovery in 1880. However, in 1884, Fahlberg went on to patent and mass-produce saccharin without ever mentioning Remsen. Fahlberg grew wealthy, while Remsen merely grew irate (Priebem and Kauffman 1980). On the matter, Remsen commented, "Fahlberg is a scoundrel. It nauseates me to hear my name mentioned in the same breath with him."

Although saccharin was commercialized not long after its discovery, it was not until sugar shortages during World War I that its use became widespread. Its popularity further increased during the 1960s and 1970s among dieters, since saccharin is a calorie-free sweetener. In the United States saccharin is often found in restaurants in pink packets; the most popular brand is "Sweet'N Low." A small number of soft drinks are sweetened with saccharin, the most popular being the Coca-Cola Company's cola drink Tab, introduced in 1963 as a diet cola soft drink.

The word saccharin has no final "e." The word saccharine, with a final "e," is much older and is an adjective meaning "sugary"âits connection with sugar means the term is used metaphorically, often in a derogative sense, to describe something "unpleasantly over-polite" or "overly sweet".[1] Both words are derived from the Greek word ÏάκÏαÏον (sakcharon, German âchâ sound), which ultimately derives from Sanskrit for sugar, sharkara (शरà¥à¤à¤°à¤¾), which literally means gravel.[2]

Saccharin and human health

There have been worries about the safety of saccharin since its introduction, with investigations in the United States beginning in the early 1900s.

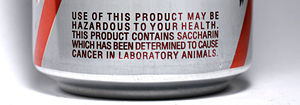

Throughout the 1960s, various studies suggested that saccharin might be an animal carcinogen. Concern peaked in 1977, after the publication of a study indicating an increased rate of bladder cancer in rats fed large doses of saccharin. In that year, Canada banned saccharin while the United States Food and Drug Administration also proposed a ban. At the time, saccharin was the only artificial sweetener available in the U.S., and the proposed ban met with strong public opposition, especially among diabetics. Eventually, the U.S. Congress placed a moratorium on the ban, requiring instead that all saccharin-containing foods display a warning label indicating that saccharin may be a carcinogen. This warning label requirement was lifted in 2000.

Many studies have been performed on saccharin since 1977, some showing a correlation between saccharin consumption and increased frequency of cancer (especially bladder cancer in rats) and others finding no such correlation. The notorious and influential studies published in 1977 have been criticized for the very high dosages of saccharin that were given to test subject rats; dosages were commonly hundreds of times higher than "normal" ingestion expectations would be for a consumer.

No study has ever shown a clear causal relationship between saccharin consumption and health risks in humans at normal doses, though some studies have shown a correlation between consumption and cancer incidence (Weihrauch and Diehl 2004). There are additional criticisms of studies showing a linkage of saccharin and cancer based the view that the biological mechanism believed to be responsible for rat cancers is inapplicable to humans and that there was possible contamination, as well as criticism of the use of the Fischer 344 Rat as a specimen for testing cancers when it was found out that these laboratory animals developed cancer spontaneously when injected with pure water only (IARC 1999).

Saccharin and the U.S. approval process

Starting in 1907, saccharin came under the examination and scrutiny of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). As Theodore Roosevelt took the office of the President of the United States, an intense debate questioned the safety of the artificial sweetener. The initial series of investigations begun by the USDA in 1907 were a direct result of the Pure Food and Drug Act. The act, passed in 1906, came after a storm of health controversies surrounding meat-packing and canning. Most notably, Upton Sinclair's book entitled "The Jungle," published in 1906, particularly influenced the American public, bringing to light many of the health issues surrounding the meat-packing industry.

Sparked by the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, saccharin was investigated by the "poison squad," led by Harvey W. Wiley's assertion that it caused digestive problems (Priebem and Kauffman 1980). Harvey Wiley was one particularly well-known figure involved in the investigation of saccharin. Wiley, then the director of the bureau of chemistry for the United States Department of Agriculture, had suspected saccharin to be damaging to human health. This opinion clashed strongly with President Theodore Roosevelt. Commenting on the questionable safety of saccharin, Theodore Roosevelt (who was at the time dieting on orders from his physician to lower his risk for diabetes) once said directly to Wiley, "Anyone who thinks saccharin is dangerous is an idiot."

The controversy continued with the prohibition of saccharin during the Taft administration. In 1911, Food Inspection Decision 135 stated that foods containing saccharin were adulterated. However in 1912, Food Inspection Decision 142 stated that saccharin was not harmful. Studies and legal controversy fueled the heated debate of this prohibition until the outbreak of the first World War. During World War I, the United States experienced a sugar shortage; the prohibition of saccharin was lifted to balance the demand for sugar. The widespread production and use of saccharin continued through World War II, again alleviating the shortages during war time but immediately slowing at the war's end (Priebem and Kauffman 1980).

In 1969, files were discovered from the Food and Drug Administration investigations from 1948 and 1949 and this stirred more controversy. These investigations, which had originally argued against saccharin use, were shown to prove little about saccharin being harmful to human health. In 1972, the USDA made an attempt to completely ban the substance from being used in anything (Preibe and Kauffman 1980). Concern peaked in 1977 after the controversial study of increased cancer in rats, but a proposed ban met with strong opposition and was modified to a warning label on products. In 1991, after 14 years, the Food and Drug Administration formally withdrew its 1977 proposal to ban the use of saccharin, and in 2000, the U.S. Congress repealed the law requiring saccharin products to carry health warning labels.

See also

Notes

- â Dictionary.com dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- â Online Etymology Dictionary Retrieved January 14, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ager, D. J., D. P. Pantaleone, S. A. Henderson, A. R. Katritzky, I. Prakash, and D. E. Walters. 1998. Commercial, synthetic nonnutritive sweeteners. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 37: 1802-1817.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). 1999. Saccharin and its salts ICHEM. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- Priebe, P. M., and G. B. Kauffman. 1980. Making government policy under conditions of scientific uncertainty: A century of controversy about saccharin in Congress and the laboratory. Minerva 18(4): 556-574.

- Weihrauch, M. R., and V. Diehl. 2004. Artificial sweeteners: Do they bear a carcinogenic risk? Annals of Oncology 15(10): 1460-1465.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.