| Pituitary gland | |

|---|---|

| Located at the base of the skull, the pituitary gland is protected by a bony structure called the sella turcica of the sphenoid bone | |

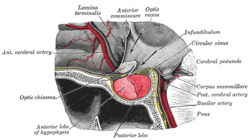

| Median sagittal through the hypophysis of an adult monkey Semidiagrammatic | |

| Latin | hypophysis, glandula pituitaria |

| Gray's | subject #275 1275 |

| Artery | superior hypophyseal artery, infundibular artery, prechiasmal artery, inferior hypophyseal artery, capsular artery, artery of the inferior cavernous sinus[1]

Vein = |

| Precursor | neural and oral ectoderm, including Rathke's pouch |

| MeSH | Pituitary+Gland |

| Dorlands/Elsevier | h_22/12439692 |

The pituitary gland, or hypophysis, is an endocrine gland located near the base of vertebrate brain, and that produces secretions that stimulate activities in other endocrine glands, impacting metabolism, growth, and other physiological processes. The pituitary gland is sometimes called the "master gland" of the body, since all other secretions from endocrine glands depend on stimulation by the pituitary gland.

In general, the cells, tissues, and organs of the endocrine system make hormones, which complement the nervous system in carrying out coordinating functions. The most complex organ of the endocrine system, both functionally and structurally, is the pituitary gland. This gland is found in all vertebrates‚ÄĒmammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish‚ÄĒand is similar in location, structure, and function in these diverse groups.

The pituitary gland reveals aspects of the remarkable coordination within vertebrates. Hormones produced in this gland at the base of the brain travel to other parts of the body, impacting particular targeted cells. After the desired impact is made, homeostasis is restored. Underlying all of this harmony is the concept of dual purposes, whereby the pituitary gland both advances its own maintenance and development (taking in nutrients, eliminating wastes, etc.) while providing a function for the entire body. These two function work together‚ÄĒonly by having a healthy pituitary can the body be aided.

Overview

In vertebrates, the pituitary gland is actually two fused glands, the anterior pituitary and the posterior pituitary. Each gland is made up of different tissue types. Some verterbrates, like fish, however, have a third distinct intermediate section.

In humans, the pituitary gland is about the size of a bean and sits at the base of the brain. It is located in a small, bony cavity called the pituitary fossa, which is situated in the sphenoid bone in the middle cranial fossa. The pituitary gland is connected to the hypothalamus of the brain by the infundibulum and is covered by the sellar diaphragm fold. The individual glands (anterior and posterior pituitary) merge during embryonic development. The tissue that forms the roof of the mouth also forms the anterior pituitary, a true endocrine gland of epithelial origin. The posterior pituitary, on the other hand, is an extension of neural tissue. The pituitary gland as it is known in humans is described in greater detail below.

The pituitary gland secretes various hormones regulating homeostasis, including trophic hormones that stimulate other endocrine glands. It also secretes hormones for sexual eminence and desires. Research has shown the importance of the anterior pituitary in the controlling of the sex cycle in vertebrates.

Sections

Located at the base of the brain, the pituitary is functionally linked to the hypothalamus. It is divided into two lobes: the anterior or front lobe (adenohypophysis) and the posterior or rear lobe (neurohypophysis).

Anterior pituitary (adenohypophysis)

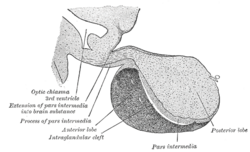

The anterior lobe is derived from the invagination of the oral musocsa called Rathke's pouch. The lobe is usually divided into three regions:

- pars distalis ("distal part") ‚ÄĒ the majority of the anterior pituitary

- pars tuberalis ("tubular part") ‚ÄĒ a sheath extending up from the pars distalis and wrapping around the pituitary stalk

- pars intermedia ("intermediate part") ‚ÄĒ sits between the bulk of the anterior pituitary and the posterior pituitary; often very small in humans

The function of the tuberalis is not well characterized, and most of the rest of this article refers primarily to the pars distalis.

The anterior pituitary is functionally linked to the hypothalamus via the hypophyseal-portal vascular connection in the pituitary stalk. Through this vascular connection, the hypothalamus integrates stimulatory and inhibitory central and peripheral signals to the five phenotypically distinct pituitary cell types.

The anterior pituitary synthesizes and secrets six important endocrine hormones:

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)

- Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)

- Prolactin

- Growth hormone (also called somatotrophin)

- Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH)

- Leutinizing hormone (LH)

These hormones are released from the anterior pituitary under the influence of hypothalamic hormones. The hypothalamic hormones travel to the anterior lobe by way of a special capillary system, called the hypothalamic-hypophyseal portal system. Once the hormone is released, it either targets another gland (or organ) or it controls the secretion of another hormone from a gland. In that case, the first hormone is called a trophic hormone.

The control of hormones from the anterior pituitary exerts a negative feedback loop. Their release is inhibited by increasing levels of hormones from the target gland on which they act.

Posterior pituitary (neurohypophysis)

Despite its name, the posterior pituitary gland is not a gland, per se; rather, it is largely a collection of axonal projections from the hypothalamus that terminate behind the anterior pituitary gland. Classification of the posterior pituitary varies, but most sources include the three regions below:

- pars nervosa, or neural/posterior lobe ‚ÄĒ constitutes the majority of the posterior pituitary, and is sometimes (incorrectly) considered synonymous with it

- infundibular stalk ‚ÄĒ also known as the "infundibulum" or "pituitary stalk"; the term "hypothalamic-hypophyseal tract" is a near-synonym, describing the connection rather than the structure

- median eminence ‚ÄĒ this is only occasionally included as part of the posterior pituitary; some sources specifically exclude it

The posterior lobe is connected to the hypothalamus via the infundibulum (or stalk), giving rise to the tuberoinfundibular pathway. Hormones are made in nerve cell bodies positioned in the hypothalamus, and these hormones are then transported down the nerve cell's axons to the posterior pituitary. They are stored in the posterior pituitary in cell terminals until a stimulus reaches the hypothalamus, which then sends an electrical signal to the posterior pituitary to release the hormone(s) into circulation.

The hormones released by the posterior pituitary are:

- Oxytocin

- Antidiuretic hormone (ADH, also known as vasopressin and AVP, arginine vasopressin)

Intermediate lobe

There is also an intermediate lobe in many animals. For instance, in fish it is believed to control physiological color change. In adult humans, it is just a thin layer of cells between the anterior pituitary and posterior pituitary, nearly indistinguishable from the anterior lobe. The intermediate lobe produces melanocyte-stimulating hormone or MSH, although this function is often (imprecisely) attributed to the anterior pituitary.

Functions

The pituitary gland helps control the following body processes through secretion and release of various hormones:

- Human development and growth ‚ÄĒ ACTH and GH

- Blood pressure (through water reabsorption)‚ÄĒ ADH/vasopressin

- Some aspects of pregnancy and childbirth, including stimulation of uterine contractions during childbirth ‚ÄĒ oxytocin

- Breast milk production ‚ÄĒ prolactin

- Sex organ functions in both women and men ‚ÄĒ FSH and LH

- Thyroid gland function ‚ÄĒ TSH

- Metabolism (conversion of food into energy) ‚ÄĒ TSH

- Water and osmolarity regulation in the body (in kidneys)‚ÄĒ ADH/vasopressin

Pathology

Variances from normal secretion of hormones can cause a variety of pathologies in the human body. Hypersecretion of a hormone exaggerates its effects, while hyposecretion of a hormone either diminishes or all together eliminates the effects of the hormone. Common disorders involving the pituitary gland include:

| Condition | Direction | Hormone |

| Acromegaly | overproduction | growth hormone |

| Growth hormone deficiency | underproduction | growth hormone |

| Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone | overproduction | vasopressin |

| Diabetes insipidus | underproduction | vasopressin |

| Sheehan syndrome | underproduction | prolactin |

| Pituitary adenoma | overproduction | any pituitary hormone |

| Hypopituitarism | underproduction | any pituitary hormone |

Additional images

See also

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Gibo, H., M. Hokama, K. Kyoshima, and S. Kobayashi. 1993. ‚ÄúArteries to the pituitary.‚ÄĚ Nippon Rinsho 51(10): 2550-2554. PMID 8254920.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Matthews, S. A. 1976. ‚ÄúThe relationship between the pituitary gland and the gonads in fundulus.‚ÄĚ Biological Bulletin 76: 241-250. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Merck Source. 2004. ‚ÄúNeurohypophysis.‚ÄĚ Dorlands Medical Dictionary: W.B. Saunders. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Silverthorn, D. 2004. Human Physiology, An Integrated Approach, 3rd ed. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 013102153

External links

All links retrieved November 24, 2022.

| Endocrine system - edit |

|---|

| Adrenal gland | Corpus luteum | Hypothalamus | Kidney | Ovaries | Pancreas | Parathyroid gland | Pineal gland | Pituitary gland | Testes | Thyroid gland |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.