House of Nemanjić

The House of Nemanjić (Serbian: Немањићи, Nemanjići; Anglicized: Nemanyid; German: Nemanjiden) was a medieval Serbian ruling dynasty which presided over the short-lived Serbian Empire from 1346 to 1371. The House was a branch of the House of Vlastimirović, whose rulers established the Serb state. The "Stefan" dynasty - House of Nemanjić was named after Stefan Nemanja (later known as Saint Simeon, the first Serbian saint). The House of Nemanjić produced eleven Serbian monarchs between 1166 and 1371 when Serbia disintegrated into many smaller states until all of these were conquered by the Ottoman Empire. Under the Vlastimirović dynasty, Serbia became Christian; under the Nemanjić rulers, the self-governing Serbian Orthodox Church was born. The first archbishop was the Prince's son. Father and son were both canonized. Subsequent rulers based their right to rule on the claim that St. Simeon now protected the Serb state. Serbian culture took shape under their rule. When the Serb state was reborn in the early nineteenth century, it was regarded as a revival of the medieval Empire. By 1918, the Serbs had united with other Balkan nations to form what after 1921 was known as Yugoslavia. This entity would be dominated by Serbs through until it collapsed in 1990.

Serbs, like any people, have a right to be proud of their history, of their distinctive culture and sense of identity, having preserved this despite foreign domination and centuries of conflict. Unfortunately, this pride has at times led some Serbs to see others as a threat to the purity of their heritage. Both during the Yugoslavian period and in the conflict that swept through the Balkans after Yugoslavia's collapse, some Serbs demonized others and tried to "cleanse" Greater Serbia of those whose presence, in their view, contaminated that space. As humanity matures and develops, the desire to dominate or even to exterminate others will hopefully yield to new ways of cooperation and co-existence, in which each people preserve their distinctive legacies, treat others with respect and benefit from mutual exchange. The ability to regard all people, with their distinct and diverse cultures, as members of a single inter-dependent family will prove essential for the survival of the planet itself.

History

Rulers of the dynasty were known as Grand Princes of Rascia from 1166. After the crowning of Stefan the First-Crowned in 1217, the full title of the dynasty became King of the land of Rascia, Doclea, Travunia, Dalmatia and Zachlumia, although a shorter version of the title was King of the Serbs. After 1346 they became Tsar of all the Serbs.

Origins

By 960, Serbia, united under the Vukanović rulers who trace themselves back to the Unknown Archont, who led the Serbs into the Balkans in the seventh century, the state disintegrated into smaller entities. Stefan Nemanja, related to the previous dynasty, was born in the small state of Zeta and despite his ancestry was raised in humble circumstances. However, when he reached his maturity he was made ruler of several of the fragmented Serbian states and began the task of reunifying the Serb nation. Challenged by his brother, Tihomir, he first defeated him then crushed a large Byzantine army sent to restore order and Byzantine suzerainty in the Balkans. He appears to have struggled for supremacy against four brothers.[1] Subsequently, he adopted the title "Grand Prince." Stefan ruled until 1168 when the Byzantine Emperor countered, sending an even larger force. Stefan surrendered and was taken captive to Constantinople. There, he was made to undergo a humiliating ceremony kneeling bareheaded, barefooted with a rope around his neck.[2] Yet, he so impressed the emperor, Manuel I Komnenos that the two became friends and when Stefan vowed that he would never again attack Byzantium, he was restored as Grand Prince. His second reign was from 1172 until 1196. After Manuel's death in 1180 he no longer considered himself bound by his oath, and led a period of further Serbian expansion at the cost of Byzantium.

After Stefan Nemanja had taken Stefan as his name, all the subsequent monarchs of the house used it as sort of title. Soon it became inseparable from the monarchy, and all claimants denoted their royal pretensions by using the same name, in front of their original names.

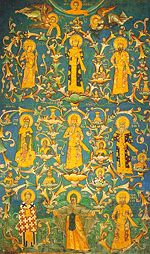

The Founder and the Serbian Church

In 1196, Stefan abdicated in favor of his middle son and a peaceful transfer of power followed. He convened a Church synod to oversee and sanction this process.[3] Taking the religious name of Simeon, Stefan joined his younger son as a monk at Mount Athos. He had founded many Churches and monasteries during his reign. His son was canonized as Saint Savos in 1253. His feast day is January 14. He is considered to the patron saint of schools and of school children. Nemanja became St. Simeon, canonized in 1200, with his feast-day on February 26. It was St. Sava who persuaded the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople to grant the Serbia Church autocephalous status. This made it a (self-governing) body. Sava became its archbishop, consecrated in 1219. Father and son together repaired the abandoned "Hilandar monastery," which would "play an incomparable role in the religious and cultural history of Serbia."[4] Fine describes the monastery as the "cultural center of the Serbs."[3] Saints Simeon and Savos dominated Serbian devotion so much that the earlier Saints Cyril and Methodius, credited with evangelizing Serbia, receded in popularity. St. Simeon was later considered to be the patron saint of Serbia. Members of the dynasty claimed the protection of these saints, and based their right to rule of descent from St. Simeon.[5]

The Imperial Period

It was Stefan Dusan (1331-1355) who transformed Serbia into one of the largest states in Europe at the time, taking the title Emperor (Tsar) in 1346. His title was Tsar of All Serbs, Albanians, Greeks and Bulgarians. Earlier, the Bulgarians had at times dominated the region, making Serbia a vassal, now it was Serbia's turn to rule Bulgaria.

The Serbian Empire did not survive its founder for very long. After 1171 it fragmented into smaller states. Throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, constant struggles between various Serbian kingdoms on one side, and the Ottoman Empire on the other side, took place. Belgrade was the last major Balkan city to endure Ottoman onslaughts, as it joined the Catholic Kingdom of Hungary to resist the Ottoman advance. Serbs, Hungarians and European crusaders heavily defeated the Turkish in the Siege of Belgrade of 1456. After repelling Ottoman attacks for over 70 years, Belgrade finally fell in 1521

Crest

The family crest was a bicephalic argent eagle on a red shield, inherited from the Byzantine Paleologus dynasty.

Rulers

- Stefan Nemanja also Stefan I, Nemanja (ca 1166-1199)

- Vukan II Nemanjić (1196-1208)

- Stefan Prvovenčani (Stefan the Firstcrowned) also Stefan II, Nemanja (1199-1228), eldest son of Stefan Nemanja

- Đorđe Nemanjić (1208-1243), Ruler of Zeta

- Stefan Radoslav (1228-1233)

- Stefan Vladislav I (1234-1243)

- Stefan Uroš I (1243-1276)

- Stefan Dragutin (1276-1282)

- Stefan (Uroš II) Milutin (1282-1321)

- Stefan Vladislav II (1321 - about 1325)

- Stefan (Uroš III) Dečanski (1321-1331)

- Stefan (Uroš IV) Dušan (Dušan the Mighty) (1331-1355), King of Serbia (1331-1346); Tsar of Serbs and Greeks (1346-1355)

- Stefan Uroš V (Uroš the Weak) (1355-1371), tsar

- Tsar Simeon-Siniša of Epirus (1359-1370), son of Stefan Uroš III and the Greek Princess

- Tsar Jovan Uroš of Epirus (1370-1373), son of Simeon-Siniša; is the very last ruler of Epirus

Legacy

The current the Karađorđević dynasty that led the national uprising against the Ottomans at the beginning of the nineteenth century, regards itself as the successor of the House of Nemanjić.[6] Karađorđe led the uprising from 1804 to 1813. His son, Alexander, became Prince of Serbia in 1842. His son, Peter, was King of Serbia (1903-1918) then, following the union between Serbia and other Balkan states, he was King of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (1918-1921). His son, Alexander I changed the name of the Kingdom to Yugoslavia in 1921. Yugoslavia ceased to be a monarchy after World War II but for the Serbs who dominated the state, often at the cost of other national groups, it was always regarded as the revived Greater Serbia of the days of the House of Nemanjić, especially of the imperial period. When Yugoslavia collapsed in the early 1990s, some Serbs were reluctant to abandon their Greater Serbia and a series of wars followed in which they tied to hold Yugoslavia together. Pride in their own identity, closely associated with the Serbian Orthodox Church which at times encouraged hostility towards and even hatred of others, resulted in periods when Serbs denied that other national groups has any right to occupy "Serbian space." This space extended into other Balkan territories because they had been ruled by Serbia during the imperial era. Muslims in Bosnia were especially targeted. It was the Ottomans who had defeated and conquered the fragmented Serbian states after the collapse of the Nemanjić dynasty, in the process killing Prince Lazar, who became a Christ like figure in Serb myth. This was at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. Muslims were demonized in much Serbian literature. The Serbian Church set out to canonize Lazar immediately after his death; he was especially venerated by the "monks of Mount Athos."[7] It has been said that it was St. Sava who enabled the Serbs to endure martyrdom on the battlefield of Kosovo.[8]

Serbs, like any people, have a right to be proud of their history, of their distinctive culture and sense of identity, having preserved this despite foreign domination and centuries of conflict. Much of what Serbs look upon with justifiable pride, including the founding of their Church, dates from the period when the House of Nemanjić ruled. An anti-Ottoman rebellion in 1593 was called the "St. Savo rebellion." After this, his remains were incinerated by the Turkish authorities.[9]. Unfortunately, at times, this national pride has led some Serbs to see others as a threat to the purity of their heritage. Denying that other national groups have any right to occupy "Serbian space," they have attempted to "cleanse" what they saw as Serbian land from alien contamination. National pride served to demonize others, thus also diminishing the humanity of Serbs themselves. As humanity matures and develops, the desire to dominate or even to exterminate others will hopefully yield to new ways of cooperation and co-existence, in which each people preserve their distinctive legacies, treat others with respect and benefit from mutual exchange. The ability to regard all people, with their distinct and diverse cultures, as members of a single inter-dependent family will prove essential for the survival of the planet itself.

See Also

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fine, John V.A. 1994. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472082605.

- Sterk, Andrea. 2004. Renouncing the World Yet Leading the Church: The Monk-Bishop in Late Antiquity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674011892.

- Velikonja, Mitja. 2003. Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. College Station, TX: Texas A & M University Press. ISBN 9781585442263.

- Wells, Florian Stone. 2008. The Sword and the Shield of the Realm. Boulder, CO: Sapientus. ISBN 9780979957703.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.