Gospel of Judas

The Gospel of Judas, a second century Gnostic gospel, was discovered in the twentieth century and publicly unveiled in 2006. It portrays the apostle Judas Iscariot, one of the twelve apostles of Jesus, in a more positive light than can be found in the New Testament accepted by Christianity. According to the traditional canonical Gospels, Judas betrayed Jesus to the Great Sanhedrin, which officiated over his crucifixion. The Gospel of Judas instead presents this act as one performed in obedience to the instructions of Jesus. Such a portrayal of the "betrayal" of Jesus is consistent with the Gnostic notion that the human form is a prison of the spirit within; thus Judas helped to release the spirit of Christ from the physical constraints of his body. An alternate reading of the Gospel's incomplete text suggests it is really saying that Judas was possessed by a demon.[1]

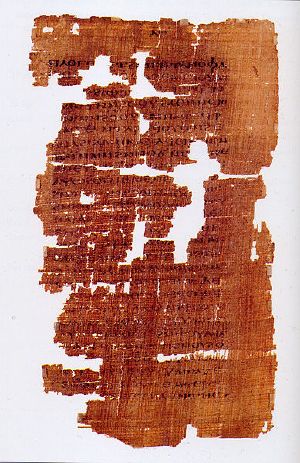

The papyrus has been carbon-dated to approximately the third to fourth century C.E., and its text points to a date in the second century, as evidenced by its introduction and epilogue, which assume the reader is familiar with the canonical Gospels. The gospel of Judas contains no references supporting the view that Judas himself was its author, but rather that it was written by Gnostic followers of Jesus the Christ. Still, there are nagging questions about whether the document could be a modern forgery.

Background

During the second and third centuries C.E., various semi-Christian and non-Christian groups composed texts that are loosely labeled as New Testament Apocrypha, which were usually (but not always) written in the names of apostles, patriarchs or other persons mentioned in the Old Testament, New Testament or older Jewish apocryphal literature.[2] The gospel of Judas is one of these texts and is so described by the only two references to it in antiquity.

Mention in Antiquity

The manuscript called Codex Tchacos, the only known manuscript that includes the text of the Gospel of Judas, surfaced in the 1970s in Egypt as a leather-bound papyrus manuscript. The papyri on which the Gospel is written is now in over a thousand pieces, possibly due to poor handling and storage, with many sections missing. In some cases, there are only scattered words; in others, many lines. According to Rodolphe Kasser, the codex originally contained 31 pages, with writing on front and back; but when it came to the market in 1999, only 13 pages, with writing on front and back, remained.[3] It is speculated that individual pages had been removed and put up for sale. The early Christian writer Irenaeus of Lyons, whose writings were almost all directed against Gnosticism, mentions The Gospel of Judas in Book 1 Chapter 31 of Refutation of Gnosticism calling it a "fictitious history." His death around 200 C.E. presents a terminus ante quem for its date of origin.

It was also referred to by Origen in the year 230 C.E. in his book Stromateis, which indirectly attacked Gnosticism.

Dating and Authenticity

Due to textual analysis for features of dialect and Greek loan words, academics who have analyzed the Gospel of Judas, which is written in the Coptic language, believe that it is probably a translation from an older Greek manuscript dating to approximately 130‚Äď180 C.E.[4] Additionally, the references to the gospel found in early church writings (mentioned above) offer another way to date the text by providing a definite end point to its composition.

The existing manuscript was radiocarbon dated to be "between the third and fourth century" according to Timothy Jull, a carbon-dating expert at the University of Arizona's physics centre. Only sections of papyrus with no text were carbon dated.

Nevertheless, there are nagging questions about whether the document could be a modern forgery. Doubts arise from a grammatical error carried over from a published copy of the Nag Hammadi text of the Apocryphon of John and a modern-sounding polemic against homosexual priests. If so, the forger would have to be a modern scholar of who knew second-century Coptic and who had access to an old papyrus that would yield the early radiocarbon date.[5]

Content

Like many Gnostic works, the Gospel of Judas claims to be a secret account, specifically "the secret account of the revelation that Jesus spoke in conversation with Judas Iscariot."

Over the ages, many philosophers have contemplated the idea that Judas was required to have carried out his actions in order for Jesus to have died on the cross and hence fulfill theological obligations. However, the Gospel of Judas asserts that Judas was acting on the orders of Jesus himself.

The Gospel of Judas states that Jesus told Judas "You shall be cursed for generations." It then adds to this conversation that Jesus had told Judas "you will come to rule over them," and that "You will exceed all of them. For you will sacrifice the man that clothes me."

Unlike the four canonical gospels, which employ narrative accounts of the last year of life of Jesus (three years in the case of John) and of his birth (only in the case of Luke and Matthew), the Judas gospel takes the form of dialogues between Jesus and Judas (and Jesus and the 12 disciples) without being embedded in any narrative or worked into any overt philosophical or rhetorical context. Such dialogue gospels were popular during the early decades of Christianity.

Like the canonical gospels, the Gospel of Judas portrays the scribes as wanting to arrest Jesus, and offering Judas money to hand over Jesus to them. However, unlike the Judas of the canonical gospels, who is portrayed as a villain, and chastised by Jesus, "Alas for that man by whom the Son of Man is betrayed. It would be better for that man if he had never been born," (Mark 14:21; Matthew 26:24) (trans. The New English Bible), the Judas gospel portrays him as a divinely appointed instrument of a grand and predetermined purpose. "In the last days they will curse your ascent to the holy (generation)."

Another portion shows Jesus favoring Judas above other disciples, saying, "Step away from the others and I shall tell you the mysteries of the kingdom," and later "Look, you have been told everything. Lift up your eyes and look at the cloud and the light within it and the stars surrounding it. The star that leads the way is your star."

The Gospel of Judas does not say that Judas hanged himself‚ÄĒindeed it seems to indicate Judas died while being stoned by the remaining eleven disciples. (He is said to have died by hanging himself in the Gospel of Matthew, Matthew 27:3-10, and by bursting open after a fall, in the Book of Acts, Acts 1: 16-19.)

Ancient controversy

Irenaeus mentions a Gospel of Judas in his anti-Gnostic work Adversus Haereses (Against Heresies), written in about 180. He writes there are some who:

…declare that Cain derived his being from the Power above, and acknowledge that Esau, Korah, the Sodomites, and all such persons, are related to themselves…. They declare that Judas the traitor was thoroughly acquainted with these things, and that he alone, knowing the truth as no others did, accomplished the mystery of the betrayal; by him all things, both earthly and heavenly, were thus thrown into confusion. They produce a fictional history of this kind, which they style the Gospel of Judas.[6]

This is in reference to the Cainites, an alleged sect of Gnosticism that especially worshipped Cain as a hero. Irenaeus alleged that the Cainites, like a large number of Gnostic groups, were semi-maltheists believing that the god of the Old Testament‚ÄĒYahweh‚ÄĒwas evil, and a quite different and much lesser being to the deity that had created the universe, and who was responsible for sending Jesus. Such Gnostic groups worshipped as heroes all the Biblical figures that had sought to discover knowledge or challenge Yahweh's authority, while demonizing those who would have been seen as heroes in a more orthodox interpretation.

The Gospel of Judas belongs to a school of Gnosticism called Sethianism, a group who looked to Adam's son Seth as their spiritual ancestor. As in other Sethian documents, Jesus is equated with Seth: "The first is Seth, who is called Christ" although this is in part of an emanationist mythology describing both positive and negative aeons.

For metaphysical reasons, the Sethian Gnostic authors of this text maintained that Judas acted as he did in order that mankind might be redeemed by the death of Jesus' mortal body. For this reason, they regarded Judas as worthy of gratitude and veneration. The Gospel of Judas does not describe any events after the arrest of Jesus.

By contrast, the Gospel of John, unlike the synoptic gospels, contains the statement of Jesus to Judas, as the latter leaves the Last Supper to set in motion the betrayal process, "Do quickly what you have to do." (John 13:27) (trans. The New English Bible). Interpretations include: this was a direct command to Judas to do what he did; Jesus was speaking to Satan rather than to Judas (thus "Satan entered into Judas"); or Jesus knew what Judas was secretly plotting.

Some two centuries after Irenaeus' complaint, Epiphanius of Salamis, bishop of Cyprus, criticized the Gospel of Judas for treating as commendable the person whom he saw as the betrayer of Jesus, and as one who "performed a good work for our salvation." (Haeres., xxxviii).

The initial translation of the Gospel of Judas, widely publicized, simply confirmed the account that was written in Irenaeus and known Gnostic beliefs, leading some scholars to simply summarize the discovery as nothing new.

However, a closer reading of the existent text, presented in October 2006, shows that Judas may have been set up to actually betray Jesus out of wrath and anger:

- "Truly [I] say to you, Judas, [those who] offer sacrifices to Saklas [… exemplify…] everything that is evil. But you will exceed all of them. For you will sacrifice the man that clothes me. Already your horn has been raised, your wrath has been kindled, your star has shown brightly, and your heart has [been hardened…]"

The initial translators might have been misled by Irenaeus' summary, which although an exciting idea was not necessarily accurate. Their theory is now in dispute.

Rediscovery

Origins

The content of the gospel had been unknown until a Coptic Gospel of Judas turned up on the antiquities "grey market," first seen under shady circumstances in a hotel room in Geneva in May 1983, when it was found among a mixed group of Greek and Coptic manuscripts offered to Stephen Emmel, a Yale Ph.D. candidate commissioned by Southern Methodist University to inspect the manuscripts. How this manuscript, Codex Tchacos, was found has not been clearly documented. However, it is believed that a now-deceased Egyptian antiquities prospector discovered the codex near El Minya, Egypt, in the neighborhood of the village Beni Masar, and sold it to a Cairo antiquities dealer called "Hanna."

Around 1970, the manuscript and most of the dealer's other artifacts were stolen by a Greek trader named Nikolas Koutoulakis, taken out of Egypt and smuggled into Geneva. Hanna managed to recover the codex by coordinating with antiquity traders in Switzerland. He then showed it to experts who recognized its significance, but it took him two decades to find a buyer who would pay the asking price of $3 million.

Sale and study

During the decades that the manuscript was for sale, no major library felt ready to purchase a codex with such questionable provenance. In 2003, Michel van Rijn started to publish material about the dubious dealings. Eventually the 62-page leather bound codex was purchased by the Maecenas Foundation in Basel, a private foundation directed by lawyer Mario Jean Roberty. Its previous owners now claimed that it had been uncovered at Muhafazat al Minya in Egypt during the 1950s or 1960s, and that its significance had not been appreciated until recently. It is worth noting that various other sites were mentioned in other negotiations.

The existence of the text was made public by Rodolphe Kasser at a conference of Coptic specialists in Paris, July 2004. In a statement issued March 30, 2005, a spokesman for the Maecenas Foundation announced plans for edited translations into English, French and German, once the fragile papyrus had undergone conservation by a team of specialists in Coptic history to be led by a former professor at the University of Geneva, Rodolphe Kasser. In January of 2005 at the University of Arizona, A. J. Tim Jull, director of the National Science Foundation Arizona AMS laboratory, and Gregory Hodgins, assistant research scientist, announced that a radiocarbon dating procedure had dated five samples from the papyrus manuscript from 220 to 340 C.E.[7] This puts this particular copy of the Coptic manuscript in the third or fourth centuries, a century earlier than had originally been thought from analysis of the script. In January 2006, Gene A. Ware of the Papyrological Imaging Lab of Brigham Young University conducted a multi-spectral imaging process on the texts in Switzerland, and confirmed their authenticity. "After concluding the research, everything will be returned to Egypt. The work belongs there and they will be conserved in the best way," Roberty has stated.[8]

Over the decades, the manuscript had been handled with less than sympathetic care and single pages had been stolen to be sold on the antiquities market (one half page turned up in Feb. 2006, in New York City. Today, the text, now in over a thousand pieces and fragments, is thought to be less than three-quarters complete. In April of 2006, an Ohio bankruptcy lawyer claimed to have several small, brown bits of papyrus that are parts of the Gospel of Judas, but he refuses to have the fragments authenticated. However, he allowed photographs to be taken of the fragments, giving access to translators.[9]

Responses and reactions

Scholarly debates

Professor Kasser revealed a few details about the text in 2004, the Dutch paper Parool reported. Its language is the same Sahidic dialect of Coptic in which Coptic texts of the Nag Hammadi Library are written. The codex has four parts: the Letter of Peter to Philip, already known from the Nag Hammadi Library; the First Apocalypse of James, also known from the Nag Hammadi Library; the first few pages of a work related to, but not the same as, the Nag Hammadi work Allogenes, and the Gospel of Judas. Up to a third of the codex is currently illegible.

A scientific paper was to be published in 2005, but was delayed. The completion of the restoration and translation was announced by the National Geographic Society at a news conference in Washington, DC on April 6, 2006, and the manuscript itself was unveiled then at the National Geographic Society headquarters, accompanied by a television special entitled The Gospel of Judas on April 9, 2006, which was aired on the National Geographic Channel.

Terry Garcia, an executive vice president of the National Geographic Society, asserted that the codex is considered by scholars and scientists to be the most significant ancient, non-biblical text to be found since the 1940s. Many copies of the Gospel of Judas appear to have been destroyed by the early Church to prevent its views from spreading, and to conform to orthodoxy. In 367 C.E., the bishop of Alexandria urged Christians to ‚Äúcleanse the church from every defilement‚ÄĚ and to reject ‚Äúthe hidden books.‚ÄĚ[10] It is possible that, in response to calls such as this one, Christians destroyed or hid most of the non-canonical gospels including the Gospel of Judas. Thus, its re-surfacing in the twentieth century was a very important event in biblical archeology and scholarship. However, James M. Robinson, one of America's leading experts on such ancient religious texts, predicted that the new book would not offer any insights into the disciple who betrayed Jesus because, though the document is old, being from the third century, the text is not old enough. According to Robinson, it was probably based on an earlier document. However, Robinson also suggested that the text would be valuable to scholars concentrating on the second century, but not because it provided a greater understanding of the Bible.

National Geographic responded to Robinson's criticism by saying that "it's ironic" for Robinson to raise such questions since he had "for years, tried unsuccessfully to acquire the codex himself, and is publishing his own book in April 2006, despite having no direct access to the materials."

Robinson describes the secretive maneuvers in the United States, Switzerland, Greece and elsewhere over two decades to sell the Judas manuscript,[11] while a novel by Simon Mawer, The Gospel of Judas (published in 2000 (UK) and 2001 (US)), revolves around the discovery of a Gospel of Judas in a Dead Sea cave and its effect on a scholarly priest.[12]

Religious responses

In his 2006 Easter address, Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury, condemned the credibility of the gospel, saying, "This is a demonstrably late text which simply parallels a large number of quite well-known works from the more eccentric fringes of the early century Church." He went on to suggest that the book's publicity derives from an insatiable desire for conspiracy theories:

We are instantly fascinated by the suggestion of conspiracies and cover-ups; this has become so much the stuff of our imagination these days that it is only natural, it seems, to expect it when we turn to ancient texts, especially biblical texts. We treat them as if they were unconvincing press releases from some official source, whose intention is to conceal the real story; and that real story waits for the intrepid investigator to uncover it and share it with the waiting world. Anything that looks like the official version is automatically suspect.[13]

The official position of the Roman Catholic Church toward the Gospel of Judas was released on April 13, 2006:

The Vatican, by word of Pope Benedict XVI, grants the recently surfaced Judas' Gospel no credit with regards to its apocryphal claims that Judas betrayed Jesus in compliance with the latter's own requests. According to the Pope, Judas freely chose to betray Jesus: "an open rejection of God's love." Judas, according to Pope Benedict XVI "viewed Jesus in terms of power and success: his only real interests lied with his power and success, there was no love involved. He was a greedy man: money was more important than communing with Jesus; money came before God and his love." According to the Pope it was these traits that led Judas to "turn liar, two-faced, indifferent to the truth," "losing any sense of God," "turning hard, incapable of converting, of being the prodigal son, hence throwing away a spent existence."[14]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ √Ä PROPOS DE LA (RE)D√ČCOUVERTE DE L‚Äô√ČVANGILE DE JUDAS Abstract by Louis Painchaud. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ J. K. Elliot (ed.), The Apocryphal New Testament, A Collection of Apocryphal Christian Literature in an English Translation (Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 0198261810).

- ‚ÜĎ Rodolphe Kasser, Marvin Meyer, and Gregor Wurst, (eds), The Gospel of Judas. (Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 2008, ISBN 142620048X).

- ‚ÜĎ Wilhelm Schneemelcher and R.M. Wilson (eds.), New Testament Apocrypha: Gospels and Related Writings Vol 1 (Louisville, KY: John Knox Press, 1990, ISBN 066422721X), 387.

- ‚ÜĎ Richard L. Arthur, The Gospel of Judas: Is it a Hoax? Journal of Unification Studies 9 (2008): 35-48. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Irenaeus, Doctrine of the Cainites Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Lori Stiles, UA Radiocarbon Dates Help Verify Coptic Gospel of Judas is Genuine UA News, March 30, 2006. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Henk Schutten, The Gospel of Judas Surfaced tertullian.org. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Lawyer Says He's Got 'Gospel of Judas' Papyrus Fragments Fox News, January 13, 2015. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Athanasius, Festal Epistles, 39.

- ‚ÜĎ James M. Robinson, The Secrets of Judas: The Story of the Misunderstood Disciple and His Lost Gospel (HarperSanFrancisco, 2006, ISBN 0061170631)

- ‚ÜĎ Simon Mawer, The Gospel of Judas: A Novel (Little Brown & Co, 2001, ISBN 0316097500).

- ‚ÜĎ Archbishop of Canterbury's sermon BBC News, April 16, 2006. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Vatican: Pope Banishes Judas' Gospel Agenzia Giornalistica Italia, April 13, 2006. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ehrman, Bart D. The Lost Gospel of Judas Iscariot: A New Look at Betrayer and Betrayed. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0195314601

- Elliot, J. K. The Apocryphal New Testament. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0198261810

- Gyllensten, Lars. Testament of Cain. Persea Books, 1982. ISBN 978-0865380196

- Kasser, Rodolphe, Marvin Meyer, and Gregor Wurst (eds.). The Gospel of Judas. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 2008. ISBN 142620048X

- Mawer, Simon. The Gospel of Judas: A Novel. Little Brown & Co, 2001. ISBN 0316097500

- Page, Gregory A. Diary of Judas Iscariot of the Gospel According to Judas. Kessinger Publishing, 2010 (original 1912). ISBN 978-1169301085

- Pagels, Elaine and Karen L. King. Reading Judas: The Gospel of Judas and the Shaping of Christianity. Viking Adult, 2007. ISBN 978-0670038459

- Robinson, James M. The Secrets of Judas: The Story of the Misunderstood Disciple and His Lost Gospel. San Francisco: Harper, 2006. ISBN 978-0061170645

- Schneemelcher, Wilhelm, and R.M. Wilson (eds.). New Testament Apocrypha: Gospels and Related Writings Vol 1. Louisville, KY: John Knox Press, 1990. ISBN 066422721X

- Wright, N. T. Judas and the Gospel of Jesus: Have We Missed the Truth about Christianity? Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0801012945

External links

All links retrieved May 24, 2024.

- Gospel of Judas Early Christian Writings.

- Judas stars as 'anti-hero' in gospel Julia Duin, Washington Times, April 7, 2006.

- The Lost Gospel of Judas Iscariot? NPR .

- The Coptic Ps.Gospel of Judas (Iscariot)

- Gospel of Judas AllAboutJesusChrist.

- Irenaeus: Against Heresies The Gnostic Society Library.

- Reactions to the Gospel of Judas

- The Betrayer's Gospel Book review by Eduard Iricinschi, Lance Jenott, Philippa Townsend. New York Review of Books, June 8, 2006.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.