Amillennialism

Amillennialism (Greek: a- "not" + Latin: mille "thousand" + annum "year") is a view in Christian eschatology named for its denial of a future thousand-year, physical reign of Jesus Christ on earth, as espoused in the premillennial and some postmillennial views of the Book of Revelation. By contrast, the amillennial view holds that the number of years in Revelation 20 is a symbolic number, not a literal description; that the millennium has already begun and is identical with the church age; and that while Christ's reign is spiritual in nature during the millennium, at the end of the church age Christ will return for the final judgment and the eternal order. Some postmillennialists and nearly all premillennialists hold that the word "millennium" should be taken to refer to a literal thousand-year period.

Although the term "amillennialism" was coined in the 1930s, this eschatological position already existed even in the first three centuries of the Christian era, during which premillennalism was popular. Augustine (354-430) systematized amillennialism, and it became the standard view not only of the Catholic Church but also the Greek Orthodox Church. It is also adhered to by "mainline" Protestant denominations such as the Lutheran, Reformed, and Anglican churches.

Terminology

The term "amillennialism" is not well compounded, as it uses the Greek prefix a- ("not") for a Latin word. It remains unclear who coined the term. But historians generally agree that the term has been widely current since sometime in the 1930s.[1][2] Before the appearance of this term, it was apparently called "anti-millennialism" or "non-millennialism" in the 1910s and 1920s.[3][4]

Many proponents dislike the name amillennialism because it unfairly suggests that they negate the biblical reference to a millennium in Revelation 20:1-6, not believing in any millennium. Given the disdain amillennialists have for the term, it is possible that it was coined by their premillennialist opponents. Although it is true that amillennialists do not believe in a literal 1000-year kingdom on earth followed by the return of Christ, they actually believe in some kind of millennium, as will be explained below. So, they prefer alternate terms such as "nunc-millennialism" (that is, now-millennialism) or "realized millennialism." But, the acceptance and wide-spread usage of these latter names has been limited.[5]

Teachings

A comparison with other types of millennialism

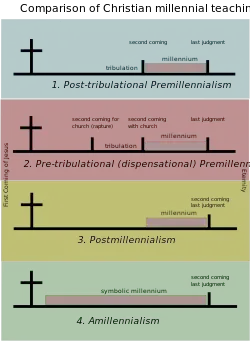

Amillennialism is differentiated from at least two other types of millennialism: premillennialism and postmillennialism. Premillennialism, although it has two distinguishable forms called pretribulationism and posttribulationism (see the chart on the right), believes in both cases that the second coming of Christ takes place before the millennial kingdom, while postmillennialism holds that it happens after the millennial kingdom. For premillennialists, the return of Christ is a cataclysmic event initiated by God to bring a very sharp break from the wicked reality of the world by inaugurating the millennial kingdom on earth. For postmillennialists, in contrast, the return of Christ happens after Christians, with the tribulation gone long before around 70 C.E. (preterism), responsibly set in motion the millennial kingdom by establishing cultural and political foundations.

Amillennialism

Amillennialism, in spite of its prefix a- ("not"), does not mean that it does not believe in a millennial kingdom at all. It only denies the existence of a literal 1000-year kingdom on earth. The millennium is a metaphor for the age of the church, and the kingdom is spiritual as Christ's reign at the right hand of God in heaven. For amillennialists, therefore, the millennial kingdom only means the church as it exists on earth, somehow pointing to the kingdom of God in heaven. This kingdom of God in heaven does not involve a direct, personal reign of Christ on earth. Rather, this kingdom in heaven is manifested only in the hearts of believers (Luke 17:20-21) as they receive the blessings of salvation (Col. 1:13-14) in the church. The age of the church, symbolized by the millennium, began with Christ's first coming and will continue until his return, and the church as a reflection of God's kingdom in heaven is considered to be far from perfect and still characterized by tribulation and suffering. For the "binding" of Satan described in Revelation has only prevented Satan from "deceiving the nations" (Rev. 20:2-3), not totally pushing him back. The forces of Satan remain just as active as always up until the return of Christ, and therefore good and evil will remain mixed in strength throughout history and even in the church, according to the amillennial understanding of the parable of the wheat and weeds (Matt. 13:24-30, 36-43).

So, although amillennialism is similar to postmillennialism in rejecting the millennium preceded by the second coming, it largely differs from the latter by denying the latter's preterist assertions that the tribulation was a past event fulfilled in the Jewish-Roman War of 66-73 C.E., and that the millennial kingdom therefore will be manifested on earth in a visible way with great political and cultural influence. According to amillennialism, it is only at the return of Christ when the final judgment takes place that the tribulation will be overcome and Satan and his followers will be destroyed. At that time, also the physical resurrection of all will take place for the final judgment, and the eternal order will begin. Thus, the physical resurrection takes place only once, although according to premillennialism a distinction should be made between the first resurrection before the millennium, the physical resurrection of the righteous dead (Rev. 20:4-5) and the second resurrection after the millennium, the physical resurrection of the wicked dead (Rev. 20:13-14). For amillennialists as well as for postmillennialists, the first resurrection does not exist as physical resurrection; it only means spiritual resurrection, which simply refers to conversion or regeneration that occurs during the millennium.

When the millennium given in Rev. 20:1-6 is interpreted by amillennialism as a metaphor for the whole age of the church, it is just like the "thousand hills" in Psalm 50:10, the hills on which God owns the cattle, are considered to refer to all hills, and the "thousand generations" in 1 Chronicles 16:15, the generations for which God will be faithful, are taken to mean all generations.

Amillennialism was popularized by Augustine in the fifth century and has dominated Christian eschatology for many centuries. Many mainline churches today continue to endorse amillennialism.

History

The early church

Although the term amillennialism, coined sometime in the 1930s, is a new term, its view is never new. The Dutch Reformed amillennialist L. Berkhof correctly observes that this view is "as old as Christianity."[6] It is true that premillennialism in its posttribulational form, known as "chiliasm" (from Greek chilioi, meaning "thousands"), flourished in the first three centuries of the Christian era, during which the Christians generally expected the imminent return of Christ in face of persecutions in the Roman Empire. But, amillennialism also existed side by side. Thus, Justin Martyr (c.100-165), who himself was a premillennialist, referred to the existence of differing views:

- I admitted to you formerly, that I and many others are of this opinion [i.e., premillennialism], and [believe] that such will take place, as you assuredly are aware; but, on the other hand, I signified to you that many who belong to the pure and pious faith, and are true Christians, think otherwise.[7]

Pseudo-Barnabas (first century), an Apostolic Father who wrote the Epistle of Barnabas, is considered to have been an amillennialist. In the second century, the Alogi (those who rejected all of John's writings) were amillennialists. So was Caius in the first quarter of the third century, as was mentioned by Eusebius of Caesarea (c.275-339) in his Church History.[8] With the influence of Neo-Platonism and the development of the allegorical interpretation of the Bible, Clement of Alexandria (c.150-215) and Origen (c.185-c.254) denied premillennialism and presented amillennialism. Likewise, Dionysius of Alexandria, pope of Alexandria from 248-265, argued that Revelation was not written by John and could not be interpreted literally; he was amillennial.[9]

Medieval and Reformation periods

Amillennialism gained ground after Christianity was legalized in the Roman Empire. It was systematized by Augustine (354-430), and this systematization carried amillennialism over as the dominant eschatology of the Medieval period. Augustine was originally a premillennialist, but he retracted that view, claiming the doctrine was carnal.[10] The Council of Ephesus in 431 condemned premillennialism as superstition. During the Medieval period, the Catholic Church suppressed radical premillennial groups such as the Franciscan Spirituals in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and the Taborites in the fifteenth century.

Augustine argued that Christ's reign was spiritual and not literal and earthly, and that the church was currently living in the millennium, but interestingly he held to a literal 1,000-year millennium that could end in perhaps 650 C.E. (based on chronological calculations from the Septuagint)[11] or, at the latest, 1000 C.E. Christ, however, did not return in any of these years. So, amillennialists afterwards decided that the millennium cover any extended period of time till the return of Christ.

Amillennialism was the dominant view also of the Protestant Reformers. They disliked premillennialism perhaps because they did not like the activities of certain Anabaptist groups who were premillennialists. The Lutheran Church formally rejected chiliasm (premillennialism0 in the the Augsburg Confession of 1530, condemning those "who now scatter Jewish opinions that, before the resurrection of the dead, the godly shall occupy the kingdom of the world, the wicked being everywhere suppressed."[12] Likewise, the Swiss Reformer Heinrich Bullinger wrote up the Second Helvetic Confession of 1566, which reads: "We also reject the Jewish dream of a millennium, or golden age on earth, before the last judgment."[13] John Calvin (1509-1564) wrote in Institutes that chiliasm (premillennialism) is a "fiction" which is "too puerile to need or to deserve refutation." He interpreted the thousand-year period of Revelation 20 non-literally, applying it to "the various troubles which await the Church militant in this world."[14]

Modern times

Amillennialism has been widely held in the Eastern Orthodox Church as well as in the Roman Catholic Church, which generally follows Augustine on this point and which has deemed that premillennialism "cannot safely be taught."[15] Amillennialism is also common among "mainline" Protestant denominations such as the Lutheran, Reformed, and Anglican churches. Amillennialism started declining in Protestant circles since the rise of postmillennialism in the eighteenth century and the resurgence of premillennialism in the nineteenth century, but it regained prominence in the West after World War II.

Criticism

Many premillennialists accuse amillennialists of over-spiritualizing parts of the Bible. In the words of the pretribulational premillennialist John Walvoord (1910-2002),

- Amillennial bibliology by its use of the spiritualizing method has departed from the proper objective interpretation of the Scriptures according to the ordinary grammatical sense of the terms, to a subjective method in which the meaning is to some extent at the mercy of the interpreter. Its subjective character has undermined amillennial theology as a whole. To the extent the spiritualizing method is used, to that very extent their theology loses all uniformity and self-consistency.[16]

Moreover, the amillennial view that good and evil will persist has led some postmillennialists to accuse amillennialists (and premillennialists) of being overly pessimistic. Amillennialists have countered that the parable of the wheat and weeds (Matt. 13:24-30, 36-43) and the parable of drawing in the net (Matt. 13:47-52) show that good and evil will be sorted out only at the end of the world. According to amillennialism, therefore, although a perfect society cannot be expected to be realized during this present age, the end of the world can be optimistically hoped for. Hence, amillennialists believe that they "adopt a position of sober or realistic optimism."[5]

Many thoughtful theologians suggest that the differences of the three main types of millennialism should not divide believers as theological views are only tentative basically.[17] If amillennialism agrees with postmillennialism on the millennium followed by the return of Christ, from there they can perhaps start to communicate to each other to assess how much pessimism or optimism they should have. Also, if amillennialism and premillennialism share almost the same degree of pessimism during the millennium, from there they can communicate to each other to assess how symbolic or literal the biblical interpretation should be to reevaluate the temporal relationship between the millennium and the return of Christ.

Notes

- ↑ Albertus Pieters, The Lamb, The Woman and The Dragon (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1937), 326.

- ↑ Robert B. Strimple, "Amillennialism," in Three Views of the Millennium and Beyond, ed. Darrell L. Bock (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1999), 83.

- ↑ C.E. Putnam, Non-Millennialism vs. Pre-Millennialism, Which Harmonizes the Word? (Chicago, IL: The Bible Institute Colportage Association, 1921), 3.

- ↑ Timothy P. Weber, Living in the Shadow of the Second Coming (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1983), 32.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Anthony Hoekema, "Amillennialism." Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ↑ L. Berkhof, Systematic Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1941), 708.

- ↑ Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, chap. 80. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ↑ Eusebius, Church History, 3.28.1-2. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ↑ Eusebius, Church History, 7.25. Retrieved December 5. 2020.

- ↑ Augustine, City of God (New York: Modern Library, 1950), 20.7.

- ↑ Oswald T. Allis, Prophecy and the Church (Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2001), 3.

- ↑ "The Augsburg Confession," Art. XVII. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ↑ "The Second Helvetic Confession." Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ↑ John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, book III, chap. 25, section 5. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ↑ Bernard LeFrois, "Eschatological Interpretation of the Apocalypse," The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 13 (1951): 17-20.

- ↑ John F. Walvoord, "Amillennialism as a System of Theology." Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ↑ For example, Michael Pahl, "A Survey of the Major Millennial Positions." Retrieved December 5, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allis, Oswald T. Prophecy and the Church. Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2001. ISBN 978-1579107093

- Augustine. City of God. New York: Modern Library, 1950. ASIN B0028NC2JE

- Berkhof, Louis. Systematic Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1996. ISBN 978-0802838209

- Bock, Darrell L., Kenneth L. Gentry Jr., Robert B. Strimple, and Craig A. Blaising. Three Views on the Millennium and Beyond. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1999. ISBN 978-0310201434

- Calvin, John. Institutes of the Christian Religion Center for Reformed Theology and Apologetics. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- "Chiliasm," Article found in The Anchor Bible Dictionary on CD-ROM. Logos Research Systems, 1997.

- Comenius, Johann Amos (ed.). The Labyrinth of the World and the Paradise of the Heart. Paulist Press, 1998. ISBN 080910489X

- Dunn, James D.G. Jews and Christians: The Parting of the Ways, A.D. 70 to 135 Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 1999. ISBN 0802844987

- Eusebius. Church History New Advent. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- Hoekema, Anthony. Amillennialism Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- Pieters, Albertus. The Lamb, The Woman and The Dragon. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1937. ASIN B000OL80JI

- Putnam, C.E. Non-Millennialism vs. Pre-Millennialism, Which Harmonizes the Word? Chicago, IL: The Bible Institute Colportage Association, 1921. ASIN B0026QKCTU

- Schaff, Philip. History of the Christian Church Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2006. ISBN 978-1565631960

- Walvoord, John F. Amillennialism as a System of Theology Bible.org. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- Weber, Timothy P. Living in the Shadow of the Second Coming. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1983. ISBN 978-0310440918

External links

All links retrieved July 25, 2023.

- A Defense of (Reformed) Amillennialism by David J. Engelsma.

- Millennium and Millenarianism Catholic Encyclopedia.

- On The Thousand Year Reign (Chiliasm) by Elder Cleopa of Romania (Easter Orthodox).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.