Difference between revisions of "Set" - New World Encyclopedia

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) |

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) m (→External links) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{started}}{{Contracted}} | {{started}}{{Contracted}} | ||

| + | {{Hiero|Set|<hiero>sw-W-t:x-E20-A40</hiero>|align=right|era=egypt}} | ||

| + | In [[Egyptian mythology]], '''Set''' (also spelled '''Sutekh''', '''Setesh''', '''Seteh''') is an ancient god, who was originally the god of the [[desert]], one of the two main [[biome]]s that constitutes [[Egypt]] (the other being the small fertile area on either side of the [[Nile]]). Despite these relatively morally-neutral origins, Set's character evolved over time, such that he eventually became characterized as the villain of the mythic system. For example, these later mythic materials describe the god murdering [[Osiris]] and contending with [[Horus]], in an attempt to usurp the celestial throne. | ||

| − | < | + | ==Set in an Egyptian Context== |

| − | + | As an Egyptian deity, Set belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system developed in the [[Nile]] river basin from earliest prehistory to 525 B.C.E.<ref>This particular "cut-off" date has been chosen because it corresponds to the Persian conquest of the kingdom, which marks the end of its existence as a discrete and (relatively) circumscribed cultural sphere. Indeed, as this period also saw an influx of immigrants from Greece, it was also at this point that the Hellenization of Egyptian religion began. While some scholars suggest that even when "these beliefs became remodeled by contact with Greece, in essentials they remained what they had always been" (Erman, 203), it still seems reasonable to address these traditions, as far as is possible, within their own cultural milieu.</ref> Indeed, it was during this relatively late period in Egyptian cultural development, a time when they first felt their beliefs threatened by foreigners, that many of their myths, legends and religious beliefs were first recorded.<ref>The numerous inscriptions, stelae and papyri that resulted from this sudden stress on historical posterity provide much of the evidence used by modern archeologists and Egyptologists to approach the ancient Egyptian tradition (Pinch, 31-32).</ref> The cults within this framework, whose beliefs comprise the myths we have before us, were generally fairly localized phenomena, with different deities having the place of honor in different communities.<ref>These local groupings often contained a particular number of deities and were often constructed around the incontestably primary character of a creator god (Meeks and Meeks-Favard, 34-37).</ref> Despite this apparently unlimited diversity, however, the gods (unlike those in many other pantheons) were relatively ill-defined. As Frankfort notes, “the Egyptian gods are imperfect as individuals. If we compare two of them … we find, not two personages, but two sets of functions and emblems. … The hymns and prayers addressed to these gods differ only in the epithets and attributes used. There is no hint that the hymns were addressed to individuals differing in character.”<ref>Frankfort, 25-26.</ref> One reason for this was the undeniable fact that the Egyptian gods were seen as utterly [[immanent|immanental]]—they represented (and were continuous with) particular, discrete elements of the natural world.<ref>Zivie-Coche, 40-41; Frankfort, 23, 28-29.</ref> Thus, those who did develop characters and mythologies were generally quite portable, as they could retain their discrete forms without interfering with the various cults already in practice elsewhere. Also, this flexibility was what permitted the development of multipartite cults (i.e. the cult of [[Amun-Re]], which unified the domains of [[Amun]] and [[Re]]), as the spheres of influence of these various deities were often complimentary.<ref>Frankfort, 20-21.</ref> | |

| + | |||

| + | The worldview engendered by ancient Egyptian religion was uniquely appropriate to (and defined by) the geographical and calendrical realities of its believer’s lives. Unlike the beliefs of the [[Hebrews]], [[Mesopotamians]] and others within their cultural sphere, the Egyptians viewed both history and cosmology as being well ordered, cyclical and dependable. As a result, all changes were interpreted as either inconsequential deviations from the cosmic plan or cyclical transformations required by it.<ref>Assmann, 73-80; Zivie-Coche, 65-67; Breasted argues that one source of this cyclical timeline was the dependable yearly fluctuations of the Nile (8, 22-24).</ref> The major result of this perspective, in terms of the religious imagination, was to reduce the relevance of the present, as the entirety of history (when conceived of cyclically) was ultimately defined during the creation of the cosmos. The only other aporia in such an understanding is death, which seems to present a radical break with continuity. To maintain the integrity of this worldview, an intricate system of practices and beliefs (including the extensive mythic geographies of the afterlife, texts providing moral guidance (for this life and the next) and rituals designed to facilitate the transportation into the afterlife) was developed, whose primary purpose was to emphasize the unending continuation of existence.<ref>Frankfort, 117-124; Zivie-Coche, 154-166.</ref> Given these two cultural foci, it is understandable that the tales recorded within this mythological corpus tend to be either creation accounts or depictions of the world of the dead and of the gods place within it. | ||

== Origins of name == | == Origins of name == | ||

The exact translation of ''Set'' is unknown for certain, but is usually considered to be either ''(one who) dazzles'' or ''pillar of stability'', one connected to the desert, and | The exact translation of ''Set'' is unknown for certain, but is usually considered to be either ''(one who) dazzles'' or ''pillar of stability'', one connected to the desert, and | ||

the other more to the institution of [[monarchy]]. It is reconstructed to have been originally pronounced *{{unicode|Sūtaḫ}} based on the occurrence of his name in [[Egyptian hieroglyphics]] (''swt{{unicode|ḫ}}''), and his later mention in the [[Coptic language|Coptic]] documents with the name ''Sēt''. | the other more to the institution of [[monarchy]]. It is reconstructed to have been originally pronounced *{{unicode|Sūtaḫ}} based on the occurrence of his name in [[Egyptian hieroglyphics]] (''swt{{unicode|ḫ}}''), and his later mention in the [[Coptic language|Coptic]] documents with the name ''Sēt''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Due to developments in the Egyptian language over the 3,000 years that Set was worshiped, by the Greek period, the ''t'' in ''Set'' was pronounced so indistinguishably from ''th'' that the Greeks spelt it as '''Seth'''. | ||

== Desert god == | == Desert god == | ||

| Line 61: | Line 67: | ||

Set & Jesus comparative video http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=6410112404402873027&q=naked+truth —> | Set & Jesus comparative video http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=6410112404402873027&q=naked+truth —> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <div class="references-small"> | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *Allen, James P. 2004. "Theology, Theodicy, Philosophy: Egypt." In Sarah Iles Johnston, ed. ''Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide.'' Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01517-7. | + | * Allen, James P. 2004. "Theology, Theodicy, Philosophy: Egypt." In Sarah Iles Johnston, ed. ''Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide.'' Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01517-7. |

| + | * Assmann, Jan. ''In search for God in ancient Egypt''. Translated by David Lorton. Ithica: Cornell University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801487293. | ||

*Bickel, Susanne. 2004. "Myths and Sacred Narratives: Egypt." In Sarah Iles Johnston, ed. ''Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide.'' Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01517-7. | *Bickel, Susanne. 2004. "Myths and Sacred Narratives: Egypt." In Sarah Iles Johnston, ed. ''Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide.'' Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01517-7. | ||

| − | *Cohn, Norman. 1995. ''Cosmos, Chaos and the World to Come: The Ancient Roots of Apocalyptic Faith.'' New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09088-9 (1999 paperback reprint). | + | * Breasted, James Henry. ''Development of religion and thought in ancient Egypt''. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. ISBN 0812210454. |

| − | *Kaper, Olaf Ernst. 1997. ''Temples and Gods in Roman Dakhlah: Studies in the Indigenous Cults of an Egyptian Oasis''. Doctoral dissertation; Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Faculteit der Letteren. | + | * Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). ''The Egyptian Book of the Dead''. 1895. Accessed at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ebod/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. |

| − | *Kaper, Olaf Ernst. 1997. "The Statue of Penbast: On the Cult of Seth in the Dakhlah Oasis". In ''[http://print.google.com/print?id=dv_2slpteq4C Egyptological Memoirs, Essays on ancient Egypt in Honour of Herman Te Velde]'', edited by Jacobus van Dijk. Egyptological Memoirs 1. Groningen: Styx Publications. 231–241, ISBN 90-5693-014-1. | + | * Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). ''The Egyptian Heaven and Hell''. 1905. Accessed at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ehh.htm sacred-texts.com]. |

| − | *Lesko, Leonard H. 1987. "Seth." In The Encyclopedia of Religion, edited by Mircea Eliade, 2nd edition (2005) edited by Lindsay Jones. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Thomson-Gale. ISBN 0-02-865733-0. | + | * Budge, E. A. Wallis. ''The gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian mythology''. A Study in Two Volumes. New York: Dover Publications, 1969. |

| + | * Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). ''Legends of the Gods: The Egyptian texts''. 1912. Accessed at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/leg/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | * Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). ''The Rosetta Stone''. 1893, 1905. Accessed at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/trs/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | * Collier, Mark and Manly, Bill. ''How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs: Revised Edition.'' Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998. ISBN 0520239490. | ||

| + | * Cohn, Norman. 1995. ''Cosmos, Chaos and the World to Come: The Ancient Roots of Apocalyptic Faith.'' New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09088-9 (1999 paperback reprint). | ||

| + | * Dunand, Françoise and Zivie-Coche, Christiane. ''Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 B.C.E. to 395 C.E.''. Translated from the French by David Lorton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004. ISBN 080144165X. | ||

| + | * Erman, Adolf. ''A handbook of Egyptian religion''. Translated by A. S. Griffith. London: Archibald Constable, 1907. | ||

| + | * Frankfort, Henri. ''Ancient Egyptian Religion''. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961. ISBN 0061300772. | ||

| + | * Griffith, F. Ll. and Thompson, Herbert (translators). ''The Leyden Papyrus''. 1904. Accessed at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/dmp/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | * Kaper, Olaf Ernst. 1997. ''Temples and Gods in Roman Dakhlah: Studies in the Indigenous Cults of an Egyptian Oasis''. Doctoral dissertation; Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Faculteit der Letteren. | ||

| + | * Kaper, Olaf Ernst. 1997. "The Statue of Penbast: On the Cult of Seth in the Dakhlah Oasis". In ''[http://print.google.com/print?id=dv_2slpteq4C Egyptological Memoirs, Essays on ancient Egypt in Honour of Herman Te Velde]'', edited by Jacobus van Dijk. Egyptological Memoirs 1. Groningen: Styx Publications. 231–241, ISBN 90-5693-014-1. | ||

| + | * Lesko, Leonard H. 1987. "Seth." In The Encyclopedia of Religion, edited by Mircea Eliade, 2nd edition (2005) edited by Lindsay Jones. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Thomson-Gale. ISBN 0-02-865733-0. | ||

| + | * Meeks, Dimitri and Meeks-Favard, Christine. ''Daily life of the Egyptian gods''. Translated from the French by G.M. Goshgarian. Ithaca, NY : Cornell University Press, 1996. ISBN 0801431158. | ||

| + | * Mercer, Samuel A. B. (translator). ''The Pyramid Texts''. 1952. Accessed online at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/pyt/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

*Osing, Jürgen. 1985. "Seth in Dachla und Charga." ''Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo'' 41:229–233. | *Osing, Jürgen. 1985. "Seth in Dachla und Charga." ''Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo'' 41:229–233. | ||

| + | * Pinch, Geraldine. ''Handbook of Egyptian mythology''. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002. ISBN 1576072428. | ||

*Quirke, Stephen G. J. 1992. ''Ancient Egyptian Religion''. New York: Dover Publications, inc., ISBN 0-486-27427-6 (1993 reprint). | *Quirke, Stephen G. J. 1992. ''Ancient Egyptian Religion''. New York: Dover Publications, inc., ISBN 0-486-27427-6 (1993 reprint). | ||

| + | * Shafer, Byron E. (editor). ''Temples of ancient Egypt''. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997. ISBN 0801433991. | ||

*Stoyanov, Yuri. 2000. ''The Other God: Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy''. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08253-3 (paperback). | *Stoyanov, Yuri. 2000. ''The Other God: Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy''. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08253-3 (paperback). | ||

| + | * Strudwick, Helen (General Editor). ''The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt''. Singapore: De Agostini UK, 2006. ISBN 1904687997. | ||

*te Velde, Herman. 1977. ''Seth, God of Confusion: A Study of His Role in Egyptian Mythology and Religion''. 2nd ed. Probleme der Ägyptologie 6. Leiden: E. J. Brill, ISBN 90-04-05402-2. | *te Velde, Herman. 1977. ''Seth, God of Confusion: A Study of His Role in Egyptian Mythology and Religion''. 2nd ed. Probleme der Ägyptologie 6. Leiden: E. J. Brill, ISBN 90-04-05402-2. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | *[http://alain.guilleux.free.fr/khargha_hibis/khargha_temple_hibis.html Le temple d'Hibis, oasis de Khargha]: ''Hibis Temple representations of Sutekh as Horus'' | + | *[http://alain.guilleux.free.fr/khargha_hibis/khargha_temple_hibis.html Le temple d'Hibis, oasis de Khargha]: ''Hibis Temple representations of Sutekh as Horus'' - retrieved July 25, 2007 |

| − | + | * [http://www.xeper.org/ Temple of Set]- retrieved July 25, 2007 | |

| − | *[http://www.xeper.org/ Temple of Set] | ||

{{Ancient Egypt}} | {{Ancient Egypt}} | ||

Revision as of 11:57, 25 July 2007

| Set in hieroglyphs | ||||||

|

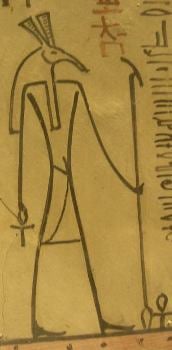

In Egyptian mythology, Set (also spelled Sutekh, Setesh, Seteh) is an ancient god, who was originally the god of the desert, one of the two main biomes that constitutes Egypt (the other being the small fertile area on either side of the Nile). Despite these relatively morally-neutral origins, Set's character evolved over time, such that he eventually became characterized as the villain of the mythic system. For example, these later mythic materials describe the god murdering Osiris and contending with Horus, in an attempt to usurp the celestial throne.

Set in an Egyptian Context

As an Egyptian deity, Set belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system developed in the Nile river basin from earliest prehistory to 525 B.C.E.[1] Indeed, it was during this relatively late period in Egyptian cultural development, a time when they first felt their beliefs threatened by foreigners, that many of their myths, legends and religious beliefs were first recorded.[2] The cults within this framework, whose beliefs comprise the myths we have before us, were generally fairly localized phenomena, with different deities having the place of honor in different communities.[3] Despite this apparently unlimited diversity, however, the gods (unlike those in many other pantheons) were relatively ill-defined. As Frankfort notes, “the Egyptian gods are imperfect as individuals. If we compare two of them … we find, not two personages, but two sets of functions and emblems. … The hymns and prayers addressed to these gods differ only in the epithets and attributes used. There is no hint that the hymns were addressed to individuals differing in character.”[4] One reason for this was the undeniable fact that the Egyptian gods were seen as utterly immanental—they represented (and were continuous with) particular, discrete elements of the natural world.[5] Thus, those who did develop characters and mythologies were generally quite portable, as they could retain their discrete forms without interfering with the various cults already in practice elsewhere. Also, this flexibility was what permitted the development of multipartite cults (i.e. the cult of Amun-Re, which unified the domains of Amun and Re), as the spheres of influence of these various deities were often complimentary.[6]

The worldview engendered by ancient Egyptian religion was uniquely appropriate to (and defined by) the geographical and calendrical realities of its believer’s lives. Unlike the beliefs of the Hebrews, Mesopotamians and others within their cultural sphere, the Egyptians viewed both history and cosmology as being well ordered, cyclical and dependable. As a result, all changes were interpreted as either inconsequential deviations from the cosmic plan or cyclical transformations required by it.[7] The major result of this perspective, in terms of the religious imagination, was to reduce the relevance of the present, as the entirety of history (when conceived of cyclically) was ultimately defined during the creation of the cosmos. The only other aporia in such an understanding is death, which seems to present a radical break with continuity. To maintain the integrity of this worldview, an intricate system of practices and beliefs (including the extensive mythic geographies of the afterlife, texts providing moral guidance (for this life and the next) and rituals designed to facilitate the transportation into the afterlife) was developed, whose primary purpose was to emphasize the unending continuation of existence.[8] Given these two cultural foci, it is understandable that the tales recorded within this mythological corpus tend to be either creation accounts or depictions of the world of the dead and of the gods place within it.

Origins of name

The exact translation of Set is unknown for certain, but is usually considered to be either (one who) dazzles or pillar of stability, one connected to the desert, and the other more to the institution of monarchy. It is reconstructed to have been originally pronounced *Sūtaḫ based on the occurrence of his name in Egyptian hieroglyphics (swtḫ), and his later mention in the Coptic documents with the name Sēt.

Due to developments in the Egyptian language over the 3,000 years that Set was worshiped, by the Greek period, the t in Set was pronounced so indistinguishably from th that the Greeks spelt it as Seth.

Desert god

As he was the god of the desert, Set was associated with sandstorms, and desert caravans. Due to the extreme hostility of the desert environment, Set was viewed as immensely powerful, and was regarded consequently as the chief god. One of the more common epithets was that he was great of strength, and in one of the Pyramid Texts it states that the king's strength is that of Set. As chief god, he was patron of Lower Egypt, where he was worshipped, most notably at Ombos. The alternate form of his name, spelt Setesh (stš), and later Sutekh (swtḫ), designates this supremacy, the extra sh and kh signifying majesty.

Set formed part of the Ennead of Heliopolis, as a son of the earth (Geb) and sky (Nut), husband to the fertile land around the Nile (Nebt-het/Nephthys), and brother to death (Ausare/Osiris), and life (Aset/Isis).

The word for desert, in Egyptian, was Tesherit, which is very similar to the word for red, Tesher (in fact, it has the appearance of a feminine form of the word for red). Consequently, Set became associated with things that were red, including people with red hair, which is not an attribute that Egyptians generally had, and so he became considered to also be a god of foreigners.[citation needed]

Set's attributes as desert god lead to him also being associated with gazelles, and donkeys, both creatures living on the desert edge. Since sandstorms were said to be under his control as lord of the desert, and were the main form of storm in the dry climate of Egypt, during the Ramesside Period, Set was identified as various Canaanite storm deities, including Baal.

The Set animal

In art, Set was mostly depicted as a mysterious and unknown creature, referred to by Egyptologists as the Set animal or Typhonic beast, with a curved snout, square ears, forked tail, and canine body, or sometimes as a human with only the head of the Set animal. It has no complete resemblance to any known creature, although it does resemble a composite of an aardvark and a jackal, both of which are desert creatures, and the main species of aardvark present in ancient Egypt additionally had a reddish appearance (due to thin fur, which shows the skin beneath it). In some descriptions he has the head of a greyhound. The earliest known representation of Set comes from a tomb dating to the Naqada I phase of the Predynastic Period (circa 4000 B.C.E.–3500 B.C.E.), and the Set-animal is even found on a mace-head of the Scorpion King, a Protodynastic ruler.

A new theory[citation needed] has it that the head of the Set animal is a representation of Mormyrus kannamae (Nile Mormyrid), which resides in the waters near Kom Ombo, one of the sites of a temple of Set, with the two square fins being what are normally interpreted as ears. However, it may be that part or all of the Set animal was based on the Salawa, a similarly mysterious canine creature, with forked tail and square ears, one member of which was claimed to have been found and killed in 1996 by the local population of a region of Upper Egypt. It may even be the case that Set was originally neither of these, but later became associated with one or both of them due to their similar appearance.

Conflict between Horus and Set

The myth of Set's conflict with Horus, Osiris and Isis appears in many Egyptian sources, including the Pyramid Texts, the Coffin Texts, the Shabaka Stone, inscriptions on the walls of the Horus temple at Edfu, and various papyrus sources. The Chester Beatty Papyrus No. 1 contains the legend known as The Contention of Horus and Set. Classical authors also recorded the story, notably Plutarch's De Iside et Osiride.

These myths generally portray Osiris as a wise king and bringer of civilization, happily married to his sister Isis. Set was his envious younger brother, and he killed and dismembered Osiris. Isis reassembled Osiris' corpse and another god (in some myths Thoth and in others Anubis) embalmed him. As the archetypal mummy, Osiris reigned over the Afterworld as judge of the dead.

Osiris' son Horus was conceived by Isis with Osiris' corpse, or in some versions, only with pieces of his corpse. Horus naturally became the enemy of Set, and many myths describe their conflicts. In some of these myths Set is portrayed as Horus' older brother rather than uncle. In one of their fights Set gouged out Horus's left eye, which represented the moon; perhaps this myth served to explain why the moon is less bright than the sun. Eventually however, using both cunning and strength, Horus vanquished and emasculated Set. The gods punished Set by forcing him to carry Osiris on his back, or by sacrificing him as a bull for their food. In some versions of the myth, Set is given dominion over the surrounding deserts as compensation for his loss of Egypt. Generally Set, as the enemy of the legitimate line of rulers, served as a symbol for disorder, evil and trickery.

The myth incorporated moral lessons for relationships between fathers and sons, older and younger brothers, and husbands and wives.

Perhaps it is also records of historical events. According to the Shabaka Stone, Geb divided Egypt into two halves, giving Upper Egypt (the desert south) to Set and Lower Egypt (the region of the delta in the north) to Horus, in order to end their feud. However, according to the stone, in a later judgment Geb gave all Egypt to Horus. Interpreting this myth as a historical record would lead one to believe that Lower Egypt (Horus' land) conquered Upper Egypt (Set's land); but in fact Upper Egypt conquered Lower Egypt. So the myth cannot be simply interpreted. Several theories exist to explain the discrepancy. For instance, since both Horus and Set were worshiped in Upper Egypt prior to unification, perhaps the myth reflects a struggle within Upper Egypt prior to unification, in which a Horus-worshipping group subjected a Set-worshiping group.

Regardless, once the two lands were united, Seth and Horus were often shown together crowning the new pharaohs, as a symbol of their power over both Lower and Upper Egypt. Queens of the 1st Dynasty bore the title "She Who Sees Horus and Set." The Pyramid Texts present the pharoah as a fusion of the two deities. Evidently, pharoahs believed that they balanced and reconciled competing cosmic principles. Eventually the dual-god Horus-Set appeared, combining features of both deities (as was common in Egyptian theology, the most familiar example being Amun-Re).

Later Egyptians interpreted the myth of the conflict between Set and Osiris/Horus as an analogy for the struggle between the desert (represented by Set) and the fertilizing floods of the Nile (Osiris/Horus).

Savior of Ra

As the Ogdoad system became more assimilated with the Ennead one, as a result of creeping increase of the identification of Atum as Ra, itself a result of the joining of Upper and Lower Egypt, Set's position in this became considered. With Horus as Ra's heir on Earth, Set, previously the chief god, for Lower Egypt, required an appropriate role as well, and so was identified as Ra's main hero, who fought Apep each night, during Ra's journey (as sun god) across the underworld.

He was thus often depicted standing on the prow of Ra's night barque spearing Apep in the form of a serpent, turtle, or other dangerous water animals. Surprisingly, in some Late Period representations, such as in the Persian Period temple at Hibis in the Khargah Oasis, Set was represented in this role with a falcon's head, taking on the guise of Horus, despite the fact that Set was usually considered in quite a different position with regard to heroism.

This assimilation also led to Anubis being displaced, in areas where he was worshipped, as ruler of the underworld, with his situation being explained by his being the son of Osiris. As Isis represented life, Anubis' mother was identified instead as Nephthys. This led to an explanation in which Nephthys, frustrated by Set's lack of sexual interest in her, disguised herself as the more attractive Isis, but failed to gain Set's attention because he was infertile. Osiris mistook Nephthys for Isis and they had conceived Anubis resulting in Anubis' birth. In some later texts, after Set lost the connection to the desert, and thus infertility, Anubis was identified as Set's son, as Set is Nephthys' husband.

If one looks in the mythology, Set has a great many wives, including some foreign Goddesses, and several children. Some of the most notable wives (beyond Nephthys/Nebet Het) are Neith (with whom he is said to have fathered Sobek), Amtcheret (by whom he is said to have fathered Upuat - though Upuat is also said to be a son of Aser/Osiris in some places), Tuaweret, Hetepsabet (one of the Hours, a feminine was-beast headed goddess who is variously described as wife or daughter of Set), and the two Canaanite deities Anat and Astarte, both of whom are equally skilled in love and war - two things which Set himself was famous for.

God of evil

Naturally, when, during the Second Intermediate Period the mysterious foreign Hyksos gained the rulership of Egypt, and ruled the Nile Delta, from Avaris, they chose Set, originally Lower Egypt's chief god, as their patron, and so Set became worshipped as the chief god once again. However, following this invasion, Egyptian attitudes towards foreigners could be best described as xenophobic, and eventually the Hyksos were deposed. During this period, Set (previously a hero), as the Hyksos' patron, came to embody all that the Egyptians disliked about the foreign rulers, and so he gradually absorbed the identities of all the previous evil gods, particularly Apep.

When the Legend of Osiris and Isis grew up, Set was consequently identified as the killer of Osiris in it, having hacked Osiris' body into pieces, dispersing them, so that he could not be resurrected. Interpreting the ears as fins, the head of the Set-animal resembles the Oxyrhynchus fish, and so it was said that as a final precaution, an Oxyrhynchus fish ate Osiris' penis.

Now that he had become the embodiment of evil, Set was consequently sometimes depicted as one of the creatures that the Egyptians most feared, crocodiles, and hippopotamus, and by the time of the New Kingdom, he was often associated with the villainous gods of other rising empires. One such case was Baal, an identification in which Set was described as being the consort of ‘Ashtart or ‘Anat, wife of Baal. Set was also identified by the Egyptians with the Hittite deity Teshub, who was a vicious storm god, as was Set.

The Greeks later linked Set with Typhon because both were evil forces, storm deities and sons of the Earth that attacked the main gods.

Some scholars hold that after Egypt's conquest by the Persian ruler Cambyses II, Set also became associated with foreign oppressors, including the Achaemenid Persians, Ptolemaic dynasty, and Romans. Indeed, it was during the time that Set was particularly vilified, and his defeat by Horus widely celebrated. Nevertheless, throughout this period, in some distant locations he was still regarded as the heroic chief deity; for example, there was a temple dedicated to Set in the village of Mut al-Kharab, in the Dakhlah Oasis.

Notes

- ↑ This particular "cut-off" date has been chosen because it corresponds to the Persian conquest of the kingdom, which marks the end of its existence as a discrete and (relatively) circumscribed cultural sphere. Indeed, as this period also saw an influx of immigrants from Greece, it was also at this point that the Hellenization of Egyptian religion began. While some scholars suggest that even when "these beliefs became remodeled by contact with Greece, in essentials they remained what they had always been" (Erman, 203), it still seems reasonable to address these traditions, as far as is possible, within their own cultural milieu.

- ↑ The numerous inscriptions, stelae and papyri that resulted from this sudden stress on historical posterity provide much of the evidence used by modern archeologists and Egyptologists to approach the ancient Egyptian tradition (Pinch, 31-32).

- ↑ These local groupings often contained a particular number of deities and were often constructed around the incontestably primary character of a creator god (Meeks and Meeks-Favard, 34-37).

- ↑ Frankfort, 25-26.

- ↑ Zivie-Coche, 40-41; Frankfort, 23, 28-29.

- ↑ Frankfort, 20-21.

- ↑ Assmann, 73-80; Zivie-Coche, 65-67; Breasted argues that one source of this cyclical timeline was the dependable yearly fluctuations of the Nile (8, 22-24).

- ↑ Frankfort, 117-124; Zivie-Coche, 154-166.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allen, James P. 2004. "Theology, Theodicy, Philosophy: Egypt." In Sarah Iles Johnston, ed. Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01517-7.

- Assmann, Jan. In search for God in ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Ithica: Cornell University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801487293.

- Bickel, Susanne. 2004. "Myths and Sacred Narratives: Egypt." In Sarah Iles Johnston, ed. Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01517-7.

- Breasted, James Henry. Development of religion and thought in ancient Egypt. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. ISBN 0812210454.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Egyptian Book of the Dead. 1895. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Egyptian Heaven and Hell. 1905. Accessed at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ehh.htm sacred-texts.com].

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. The gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian mythology. A Study in Two Volumes. New York: Dover Publications, 1969.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). Legends of the Gods: The Egyptian texts. 1912. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Rosetta Stone. 1893, 1905. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Collier, Mark and Manly, Bill. How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs: Revised Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998. ISBN 0520239490.

- Cohn, Norman. 1995. Cosmos, Chaos and the World to Come: The Ancient Roots of Apocalyptic Faith. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09088-9 (1999 paperback reprint).

- Dunand, Françoise and Zivie-Coche, Christiane. Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 B.C.E. to 395 C.E.. Translated from the French by David Lorton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004. ISBN 080144165X.

- Erman, Adolf. A handbook of Egyptian religion. Translated by A. S. Griffith. London: Archibald Constable, 1907.

- Frankfort, Henri. Ancient Egyptian Religion. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961. ISBN 0061300772.

- Griffith, F. Ll. and Thompson, Herbert (translators). The Leyden Papyrus. 1904. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Kaper, Olaf Ernst. 1997. Temples and Gods in Roman Dakhlah: Studies in the Indigenous Cults of an Egyptian Oasis. Doctoral dissertation; Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Faculteit der Letteren.

- Kaper, Olaf Ernst. 1997. "The Statue of Penbast: On the Cult of Seth in the Dakhlah Oasis". In Egyptological Memoirs, Essays on ancient Egypt in Honour of Herman Te Velde, edited by Jacobus van Dijk. Egyptological Memoirs 1. Groningen: Styx Publications. 231–241, ISBN 90-5693-014-1.

- Lesko, Leonard H. 1987. "Seth." In The Encyclopedia of Religion, edited by Mircea Eliade, 2nd edition (2005) edited by Lindsay Jones. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Thomson-Gale. ISBN 0-02-865733-0.

- Meeks, Dimitri and Meeks-Favard, Christine. Daily life of the Egyptian gods. Translated from the French by G.M. Goshgarian. Ithaca, NY : Cornell University Press, 1996. ISBN 0801431158.

- Mercer, Samuel A. B. (translator). The Pyramid Texts. 1952. Accessed online at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/pyt/index.htm sacred-texts.com].

- Osing, Jürgen. 1985. "Seth in Dachla und Charga." Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 41:229–233.

- Pinch, Geraldine. Handbook of Egyptian mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002. ISBN 1576072428.

- Quirke, Stephen G. J. 1992. Ancient Egyptian Religion. New York: Dover Publications, inc., ISBN 0-486-27427-6 (1993 reprint).

- Shafer, Byron E. (editor). Temples of ancient Egypt. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997. ISBN 0801433991.

- Stoyanov, Yuri. 2000. The Other God: Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08253-3 (paperback).

- Strudwick, Helen (General Editor). The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Singapore: De Agostini UK, 2006. ISBN 1904687997.

- te Velde, Herman. 1977. Seth, God of Confusion: A Study of His Role in Egyptian Mythology and Religion. 2nd ed. Probleme der Ägyptologie 6. Leiden: E. J. Brill, ISBN 90-04-05402-2.

External links

- Le temple d'Hibis, oasis de Khargha: Hibis Temple representations of Sutekh as Horus - retrieved July 25, 2007

- Temple of Set- retrieved July 25, 2007

| Topics about Ancient Egypt edit | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Places: Nile river | Niwt/Waset/Thebes | Alexandria | Annu/Iunu/Heliopolis | Luxor | Abdju/Abydos | Giza | Ineb Hedj/Memphis | Djanet/Tanis | Rosetta | Akhetaten/Amarna | Atef-Pehu/Fayyum | Abu/Yebu/Elephantine | Saqqara | Dahshur | |||

| Gods associated with the Ogdoad: Amun | Amunet | Huh/Hauhet | Kuk/Kauket | Nu/Naunet | Ra | Hor/Horus | Hathor | Anupu/Anubis | Mut | |||

| Gods of the Ennead: Atum | Shu | Tefnut | Geb | Nuit | Ausare/Osiris | Aset/Isis | Set | Nebet Het/Nephthys | |||

| War gods: Bast | Anhur | Maahes | Sekhmet | Pakhet | |||

| Deified concepts: Chons | Maàt | Hu | Saa | Shai | Renenutet| Min | Hapy | |||

| Other gods: Djehuty/Thoth | Ptah | Sobek | Chnum | Taweret | Bes | Seker | |||

| Death: Mummy | Four sons of Horus | Canopic jars | Ankh | Book of the Dead | KV | Mortuary temple | Ushabti | |||

| Buildings: Pyramids | Karnak Temple | Sphinx | Great Lighthouse | Great Library | Deir el-Bahri | Colossi of Memnon | Ramesseum | Abu Simbel | |||

| Writing: Egyptian hieroglyphs | Egyptian numerals | Transliteration of ancient Egyptian | Demotic | Hieratic | |||

| Chronology: Ancient Egypt | Greek and Roman Egypt | Early Arab Egypt | Ottoman Egypt | Muhammad Ali and his successors | Modern Egypt | |||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.