Sahara Desert

The Sahara, located in Northern Africa, is the world's largest hot desert and second largest desert after Antarctica at over 3.5 million square miles (9 million km²). Almost as large as the United States, it crosses the borders of eleven nations. While much of the desert is uninhabited, 12 million people are scattered across its vast expanses, not including those who live along the Nile and Niger riverbanks. The name Sahara is an English pronunciation of the Arabic word for desert.

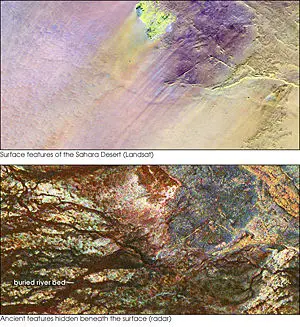

Immediately after the last ice age, the Sahara was a much wetter place than it is today. Over 30,000 petroglyphs of river animals such as crocodiles [1] exist, with half found in the Tassili n'Ajjer in southeast Algeria. Fossils of dinosaurs, including Afrovenator, Jobaria, and Ouranosaurus, have also been found here. The modern Sahara, though, is not as lush in vegetation, except in the Nile River Valley, at a few oases, and in the northern highlands, where Mediterranean plants such as cypresses and olive trees are found. The region has been this way since about 3000 b.c.e..

Geography

The boundaries of the Sahara are the Atlantic Ocean on the west, the Atlas Mountains and the Mediterranean Sea on the north, the Red Sea and Egypt on the east, and Sudan and the valley of the Niger River on the south. The Sahara is divided into western Sahara, the central Ahaggar Mountains, the Tibesti Mountains, the Aïr Mountains (a region of desert mountains and high plateaus), Tenere desert and the Libyan desert (the most arid region). The highest peak in the Sahara is Emi Koussi (3415 m) in the Tibesti Mountains in northern Chad.

The Sahara divides the continent into North and Sub-Saharan Africa. The southern border of the Sahara is marked by a band of semiarid savannas called the Sahel; south of the Sahel lies lusher Sudan and the Congo River Basin. Most of the Sahara consists of rocky hammada; ergs (large sand dunes) form only a minor part.

Regions

Although the Sahara stretches across the entire continent, it can be subdivided into distinctive regions.

- Western Sahara: a series of vast plateaus in Morocco that extend to the foothills of the Atlas Mountains. There is no surface water but dry riverbeds (wadis) that only hold water during rare rainfall. Where the underground rivers that flow from the mountains emerge on the surface, they create small oases. The area contains such minerals as phosphates, iron, zinc, and gold.

- Great Western Erg and Great Eastern Erg: An immense, uninhabited area in Algeria consisting mostly of sand dunes shaped by the wind into peaks and hollows; the two regions are separated by a rocky plateau. Precipitation is extremely low.

- Tanezrouft Desert: A rock desert in south central Algeria bisected by deep canyons and known as the "land of terror" because of its lack of water.

- Tassili N'Ajjer Desert:

Physical Features

The highest part of the desert is at the summit of Mount Koussi in the Tibesti Mountains, which is 11,204 feet (3,415 m) high. The lowest point of the Sahara is 436 feet (133 m) below sea level in the Qattara Depression in Egypt.

Climate

History

The climate of the Sahara has undergone enormous variation between wet and dry over the last few hundred thousand years. During the last ice age, the Sahara was bigger than it is today, extending south beyond its current boundaries[2]. The end of the ice age brought wetter times to the Sahara, from about 8000 B.C.E. to 6000 B.C.E., perhaps due to low pressure areas over the collapsing ice sheets to the north[3].

Once the ice sheets were gone, the northern part of the Sahara dried out. However, not long after the end of the ice sheets, the monsoon, which currently brings rain to the Sahel, came farther north and counteracted the drying trend in the southern Sahara. The monsoon in Africa (and elsewhere) is due to heating during the summer. Air over land becomes warmer and rises, pulling in cool wet air from the ocean. This causes rain. Paradoxically, the Sahara was wetter when it received more insolation in the summer. In turn, changes in solar insolation are caused by changes in the earth's orbital parameters.

By around 2500 B.C.E., the monsoon had retreated south to approximately where it is today[4], leading to the desertification of the Sahara. The Sahara is currently as dry as it was about 13,000 years ago.[5] These conditions are responsible for what has been called the Sahara Pump Theory.

Temperatures

The Sahara desert has one of the harshest climates in the world, with strong winds that blow from the northeast. Sometimes on the border zones of the north and south, the desert will receive about 10 in. (25 cm) of rain a year. The rainfall is usually torrential when it occurs after long dry periods, which can last for years. Daytime temperatures can be 58°C (136°F), but freezing temperatures are not uncommon at night. Its temperature can become as low as -6°C (22°F).

History

Egyptians and Phonecians

By 6000 B.C.E. predynastic Egyptians in the southwestern corner of Egypt were herding cattle and constructing large buildings. Subsistence in organized and permanent settlements centered predominantly on cereal and animal agriculture: cattle, goats, pigs, and sheep.[6] Metal objects replaced prior ones of stone.[6] Tanning animal skins, pottery, and weaving are commonplace in this era also.[6] There are indications of seasonal or only temporary occupation of the Al Fayyum in the 6th millennium B.C.E., with food activities centering on fishing, hunting, and food-gathering.[7] Stone arrowheads, knives, and scrapers are common.[7] Burial items include pottery, jewelry, farming and hunting equipment, and assorted foods including dried meat and fruit.[6] The dead are buried facing due west.[6]

The Phonecians created a confederation of kingdoms across the entire Sahara to Egypt, generally settling on the coasts but sometimes in the desert also.

By 2500 B.C.E. the Sahara was as dry as it is today and became a largely impenetrable barrier to humans, with only scattered settlements around the oases but little trade. The one major exception was the Nile Valley. The Nile River, however, was impassable at several cataracts, making trade and contact difficult. The earliest crossings of the Sahara, about 1000 B.C.E., were by oxen and horse, but such travel was rare until the third century C.E. when the domesticated camel was introduced.

Sometime between 633 and 530 B.C.E. Hanno the Navigator either established or reinforced Phoenician colonies in the Western Sahara, but all ancient remains have vanished with virtually no trace.

Greeks

By 500 B.C.E. a new influence arrived in the form of the Greeks and Phonecians. Greek traders spread along the eastern coast of the desert, establishing colonies along the Red Sea coast. The Carthaginians explored the Atlantic coast of the desert. The turbulence of the waters and the lack of markets never led to an extensive presence farther south than modern Morocco. Centralized states thus surrounded the desert on the north and east, but the desert itself remained outside their control. Raids from the nomadic Berber people of the desert were a constant concern of those living on the edge of the desert.

Urban civilization

An urban civilization, the Garamantes, arose around this time in the heart of the Sahara, in a valley that is now called the Wadi al-Ajal in Fazzan, Libya. The Garamantes dug tunnels far into the mountains flanking the valley to tap fossil water and bring it to their fields. The Garamantes grew populous and strong, conquering their neighbors and capturing many slaves (who were put to work extending the tunnels). The ancient Greeks and the Romans knew of the Garamantes and regarded them as uncivilized nomads. However, they traded with the Garamantes, and a Roman bath has been found in the Garamantes capital of Garama. Archaeologists have found eight major towns and many other important settlements in the Garamantes territory. The civilization eventually collapsed after they had depleted available water in the aquifers and could no longer sustain the effort to extend the tunnels.[5][8]

The Arabs

After the Arab invasion of the Sahara, trade across the desert intensified. The kingdoms of the Sahel, especially the Ghana Empire and the later Mali Empire, grew rich and powerful exporting gold and salt to North Africa. The emirates along the Mediterranean Sea sent south manufactured goods and horses. Salt was also exported south, sometimes in caravans of forty thousand camels. Timbuktu became a trading center because of its location on the Niger River. Kola nuts, leather, cotton, and slaves were traded north. This process turned the scattered oasis communities into trading centers and brought them under the control of the empires on the edge of the desert.

This trade persisted for several centuries until the development in Europe of the caravel allowed ships, first from Portugal but soon from all Western Europe, to sail around the desert and gather resources from their source. The Sahara was rapidly remarginalized.

The colonial powers also largely ignored the region, but the modern era has seen a number of mines and communities develop to exploit the desert's natural resources. These include large deposits of oil and natural gas in Algeria and Libya and large deposits of phosphates in Morocco and Western Sahara.

Contemporary peoples

Some twelve million people live in the Sahara, most of them in Egypt, Mauritania, Morocco, and Algeria. Dominant ethnicities in the Sahara are various Berber groups including Tuareg tribes, various Arabized Berber groups such as the Hassaniya-speaking Moors (also known as Sahrawis), and various "black African" ethnicities including Tubu, Nubians, Zaghawa, Kanuri, Peul (Fulani), Hausa, and Songhai.

The largest city in the Sahara is the Egyptian capital Cairo, in the Nile Valley. Other important cities are Nouakchott, the capital of Mauritania; Tamanrasset, Ouargla, Bechar, Hassi Messaoud, Ghardaia, El Oued, Algeria; Timbuktu, Mali; Agadez, Niger; Ghat, Libya; and Faya, Chad.

Flora and fauna

Animals found include antelope, gazelles, jackals, hyenas, fennec foxes, small reptiles, insects, and scorpions. The mountains provide a home for the barbary sheep, leopards, the addax, and the sand gazelle. The latter has splayed hooves that make it easier to travel in the sand. The fennec fox has large ears to dissipate heat and hairy soles to protect its feet while crossing the desert in search of lizards and locusts.

Plants such as acacia trees, palms, succulents, spiny shrubs, and grasses have adapted to the arid conditions, either by reducing water loss or storing water.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Marco C. Stoppato and Alfredo Bini, Deserts, 2003. Firefly Books, Buffalo, NY. ISBN 1552976696

- Sara Oldfield, Deserts: The Living Drylands, 2004. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. ISBN 026215112X

- Dean KIng, Skeletons on the Zahara, 2004. Little, Brown and Co., New York, NY. ISBN 0316835145

- Mark Kurlansky, Salt: A World History, 2002. Walker and Co., New York, NY. ISBN 0802713734

- Pigs in Ancient Egypt by Marie Parsons www.touregypt.net

- Michael Brett and Elizabeth Frentess. The Berbers. Blackwell Publishers. 1996.

- Charles-Andre Julien. History of North Africa: From the Arab Conquest to 1830. Praeger, 1970.

- Abdallah Laroui. The History of the Maghrib: An Interpretive Essay. Princeton, 1977.

- Hugh Kennedy. Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of al-Andalus. Longman, 1996.

- Fezzan Project - Palaeoclimate and environment - retrieved March 15, 2006

Notes

- ↑ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2002/06/0617_020618_croc.html

- ↑ Christopher Ehret. The Civilizations of Africa. University Press of Virginia, 2002.

- ↑ Fezzan Project - Palaeoclimate and environment

- ↑ Sahara's Abrupt Desertification Started By Changes In Earth's Orbit, Accelerated By Atmospheric And Vegetation Feedbacks

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 White, Kevin and Mattingly, David J. 2006. Ancient Lakes of the Sahara. American Scientist. Volume 94 Number 1 (January-February, 2006). pp. 58-65.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Predynastic (5,500 - 3,100 B.C.E.) www.touregypt.net

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Fayum, Qarunian (Fayum B) (about 6000-5000 B.C.E.?) www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk

- ↑ Keys, David. 2004. Kingdom of the Sands. Archaeology. Volume 57 Number 2, (March/April 2004)Abstract - retrieved March 13, 2006

External links

- Trans-Sahara routes

- Sahara pictures from Algerian UN Permanent Mission website

- Flora and Fauna of the Sahara (in French}

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.