Relief (sculpture)

m (→Sunken relief) |

m |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

Generally, relief figures and backgrounds are sculpted from the same material, but there are a few exceptions in [[Greek art]] and in the decorative work of the [[Chinese]] and [[Japanese]], who used inlaid [[ivory]], [[gold]] and [[cloisonné]] techniques to form reliefs. | Generally, relief figures and backgrounds are sculpted from the same material, but there are a few exceptions in [[Greek art]] and in the decorative work of the [[Chinese]] and [[Japanese]], who used inlaid [[ivory]], [[gold]] and [[cloisonné]] techniques to form reliefs. | ||

| + | [[Image:Carnegie Museum of Art - candlesticks 2.JPG|thumb|150px|Chinese cloisonné]] | ||

==Relief scupture== | ==Relief scupture== | ||

Revision as of 16:46, 3 January 2009

A relief is a sculptured art work in which figures are carved into a level plane or the plane is removed to reveal images sculpted on its surface without disconnecting them from the plane. It is therefore not free-standing or in the round, but has a background from which the main elements of the composition.

There are three basic forms of relief sculpture: bas relief (low relief), in which the sculpture is raised only slightly from the background surface; alto relievo (high relief), in which part of the sculpture is rendered in three dimensions; and intaglio (sunken relief), in which the image is carved into the surface material.

Relief sculpture has a notable history dating back over 20,000 years in both eastern and western cultures and are often found, for example, on the walls of monumental buildings. Several panels or sections of relief together may represent a sequence of scenes.

Generally, relief figures and backgrounds are sculpted from the same material, but there are a few exceptions in Greek art and in the decorative work of the Chinese and Japanese, who used inlaid ivory, gold and cloisonné techniques to form reliefs.

Relief scupture

Although clay and wood were probably the earliest mediums of bas-relief, the first preserved relief sculpture originated with the stone-cutters of pre-history. This type of art comes closest to painting, both of which have composition, perspective, and the play of light and shadow. Relief focuses more on contour than line and the use of chiaroscuro in defining form. It is believed to have pre-dated sculpture in the round, as it is easier to create than a free-standing full-figure. Bas-relief is very suitable for scenes with many figures and other elements such as a landscape or architectural background. A bas-relief may use any medium or technique of sculpture, but stone carving and metal casting are two traditional ones.

In larger reliefs marble, bronze, and terra-cotta were used. While in smaller reliefs precious metals and stones, such as ivory, stucco, enamel, and wood, are used more often. The reliefs of the Egyptians and Assyrians, not highly plastic (using both high and low indicating fludity), were made more effective by the introduction of strong colors. The early Greeks also made use of polychromy, as seen in the metope relief in the Museum of Palermo. The human form was most commonly used in the Greek and Roman classic reliefs, quite often in processional order of historic or military events, or in the ceremonial of worship. It also is well suited to the use of a series of scenes. A number of bronze doors of Italian baptisteries show illustrations of the Old and the New Testament. In Gothic art and in the Renaissance it was the custom to tint wood, terra-cotta, and stucco, but not marble or stone.

Types of relief

Low relief

A bas-relief (pronounced "bah relief"; French for "low relief" but derived from the Italian basso rilievo) is a form of surface ornamentation in which the sculpted projection is very slight or shallow. The background is very compressed or completely flat, as on most coins, on which all images are in low-relief.

The most famous example of low relief is the frieze around the cella of the Parthenon, large portions of it are in the British Museum. The lowest kind of relief is the Tuscan term, rilievo-stíacciato, this type scarcely rises from the surface upon which it is carved, and is mostly made of fine lines and delicate indentations. The best examples can be found in Donatello's Florentine Madonnas and saints.

High relief

High relief or alto-relievo, from the Italian, involves the undercutting of at least the most prominent figures of the sculpture so that they are rendered at more than 50 percent in the round against the background. However, the degree of relief may vary across a composition, with prominent features such as faces in higher relief. Themetopes from the Parthenon—now in the British Museum—is among the best-known examples of alto-rilievo.

All cultures and periods where large sculptures were created used this technique as one of their sculptural options. It is present in monumental sculpture and architecture from ancient times to present.

Sunken relief

Sunken-relief, also known as intaglio or hollow-relief, describes an image that is carved into a flat surface, with the images usually mostly linear in nature. This form is most famously associated with the Art of Ancient Egypt, where strong sunlight and resulting heavy shadow is present most of the time. Included in this category is picture-writing (hieroglyphs), which was used to inscribe images on stone monuments and Egyptian reliefs. Hieroglyphs are also seen in various kinds of metal and wood inlay.

In the sculpture of many cultures, including Europe, intaglio is mostly used for inscriptions, as often seen on headstones or buildings.

Ancient examples

Ancient cave art in the Franco-Cantabrian area of the Upper Paleolithic period included not only cave paintings and engravings but a few bas-reliefs sculpted in clay in the French Pyrenees. Ancient humans used art primarily for religious purposes and to record events in the lives of cave dwellers.

The Babylonians, Assyrians, and Hittites practiced both bas-relief and sculpture in the round. The Greeks achieved the greatest mastery by conceiving relief sculpture in a plastic sense-embodying all types of high and low together. They used relief both as an ornament and as an integral part of a plan in conjunction with architecture. In the second and first centuries B.C.E. bas-relief sculpture was present in western India. The earliest find is on the porch of a small monastery at Bhājā, thought of as being the god, Indra, seated on his elephant and Sūrya, the sun god, in his chariot. Later in the first through fourth century India CE, individually carved figures-either in high relief or in the round-replaced the earlier narrative tradition edifying rulers and gods. They used the high relief between the triglyphs and the tympana of the temples, and low or bas-relief in friezes, tombstones, etc.

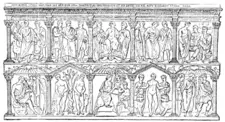

In Europe, the Hellenistic period saw a more picturesque carving style. The Etruscan's relief was mainly in artistic handicrafts. In Rome, the Arch of Titus, the continuous winding reliefs of the Column of Trajan, imperial sarcophagi (in the Vatican), and reliefs of the Capitol Museum all reflect a pictorial style, revealing the influence of the Greeks.

Christian and modern styles of relief

Early Christian examples show much similarity to antique models in the form, pose, and drapery of subjects. Most examples can be found in the sarcophagi and catacomb burials with biblical, apostolic, or symbolic subjects such as Daniel in the lions' den, Moses bringing water from the rock, the adoration of the Magi, and the Good Shepherd. The myths of heathen beliefs were sometimes utilized and changed into Christian themes, such as Ulysses attached to a mast transformed into Christ on the cross.

By the fourth century, Christian relief work of considerable quality began to emerge, such as the sarcophagus of Junius Bassus in the vaults of St. Peter's Basilica and several works in the Lateran Museum. Later basilicas, cathedrals and churches included reliefs of a Byzantine character, followed by the Frankish and Teutonic styles. The bronze reliefs of the church of St. Michael, Hildesheim, Germany are considered fine examples of the eleventh century style; those of the Golden Gate, Freiburg, are among the finest work of the late Romanesque period.

As the Romanesque period merged into the Gothic, relief sculpture developed a new character and special importance because it was used in many aspects of the architecture of the time. Relief reached its fullest development in Florence with examples like the baptistery doors of Ghiberti and the marble pulpit of Santa Croce by Benedetto da Majano. Donatello used both high and low reliefs. Michelangelo utilized bas-reliefs in his architecture and funerary work. Others continued to develop the form throughout the late Renaissance through the nineteenth-century in Europe and America, especially on civic buildings. During this period, reliefs became popular as an independent art form, especially for outdoor commemorative sculptures.

American relief

Italian relief sculptors introduced the art to the United States when they were working on the Federal buildings in Washington, D.C. The most adept American Neoclassical sculptor was the prolific relief artist, Erastus Dow Palmer (1817-1904) from Albany, New York. Originally trained as a cameo-cutter, he produced many portraits and idealized subjects which inspired other American artists including his assistants Charles Calverley and Launt Thompson. Henry Kirke Brown studied in Italy (1842 to 1846) and moved the art form from Neoclassicism to naturalism and from marble to bronze. He created bronze high-relief medallions of the American founding fathers which were highly realistic with much textural variation, strong modeling, and an authentic likeness. Augustus Saint-Gaudens was America's greatest relief sculptor and technical innovator. Also trained first as a cameo-carver, he developed a mastery in delicate cuts in shell and stone.

Inspired to "paint in bas-relief," he produced a group of portraits of artists and friends in Paris in the late 1870s. These were remarkable intimate, low-relief bronzes. His work inspired future sculptors toward greater experimentation and refinement. By World War I, relief sculptors pushed the limits of the art to more innovative approaches utilizing diverse materials, and modernist forms replacing the traditional standards. The most famous American relief is Mount Rushmore, the huge monument sculpture memorializing the great American president, started in 1927 and completed in 1941.

Contemporary reliefs can be found in the façades and interiors of numerous buildings in the United States, such as the Supreme Court in Washington, DC and in many nations of the world. Many are in the classical Roman or Greek style while others reflect a more natural approach to form, even some in an unfinished style reminiscent of Michelangelo's later sculpture.

Famous reliefs

Famous examples of reliefs include:

- Mount Rushmore National Memorial, Keystone, South Dakota, high relief

- Great Altar of Pergamon, now at the Pergamon Museum, Berlin, mostly high relief

- Lions and dragons from the Ishtar Gate, Babylon, low relief

- Temple of Karnak in Egypt, sunken relief

- Bayon, Angkor showing Cham soldiers in the boat and dead Khmer fighters in the water

- Angkor Wat in Cambodia, mostly low relief

- The images of the elephant, horse, bull and lion at the bottom of the Lion Capital of Asoka, the national symbol of India (the capital itself is a full sculpture)

- Glyphs and artwork of the Maya civilization, low relief

- The monument to the Confederacy at Stone Mountain, Georgia

- Borobudur temple, Java Island Java, Indonesia

- The Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon, now housed at the British Museum, high and low relief

- Frieze of Parnassus, high relief

- Robert Gould Shaw Memorial, Boston, mostly high relief

See also

- Mount Rushmore

- Temple of Karnak in Egypt

- Angkor Wat in Cambodia

- Lion Capital of Asoka, India

- Maya civilization

- Parthenon

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Conlin, Diane Atnally. The Artists of the Ara Pacis: The Process of Hellenization in Roman Relief Sculpture (Studies in the History of Greece and Rome), The University of North Carolina Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0807823439

- Cook, Brian. Relief Sculpture of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (Oxford Monographs on Classical Archaeology) The first complete catalog of its friezes and other decorative reliefs with descriptions. Oxford University Press, USA, 2005. ISBN 978-0198132127

- Davis, Anita Price. New Deal Art in North Carolina: The Murals, Sculptures, Reliefs, Paintings, Oils and Frescoes and Their Creators, McFarland, 2008. ISBN 978-0786437795

- Dryfhout, John, and Beverly Cox. Augustus Saint-Gaudens: The Portrait Reliefs. Exhibition catalog. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1969. ASIN B001NALPQO

- Gerdts, William H. "The Neoclassical Relief." In Perspectives on American Sculpture before 1925, (edited by Thayer Tolles) pp. 2–23. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003. ISBN 9781588391056

- Marconi, Clemente. Temple Decoration and Cultural Identity in the Archaic Greek World: The Metopes of Selinus, Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0521857970

- Rogers, L.R. Relief Sculpture (Appreciation of the Arts), Oxford University Press, 1974. ISBN 978-0192119209

- Ridgway, Brunilde S. Prayers in Stone: Greek Architectural Sculpture (c. 600-100 B.C.E.) (Sather Classical Lectures), University of California Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0520215566

- Tolles, Thayer, ed. with Lauretta Dimmick; Donna J Hassler. American Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2 vols. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999–2001. ISBN 9780870999239

External links

All links retrieved December 19, 2008.

- Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, "American Relief Sculpture", Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Melissa Hardiman, "Bas-Relief Pathfinder"

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.