Pine

| Pines | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sugar Pine (Pinus lambertiana) | ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Species | ||||||||||||

|

About 115. |

Pines are coniferous trees of the genus Pinus, in the family Pinaceae. There are about 115 species of pine. They are found naturally only in the Northern Hemisphere (with one very minor exception) where their forests dominate vast areas of land. They have been and continue to be very important to humans, mainly for their wood and also for other products. Besides that their beauty, hardiness, and beneficence have been a source of inspiration to those living in the sometimes difficult northern environments.

There are some conifers growing in the Southern Hemisphere which, although not true pines, resemble them and are sometimes called pines; for instance the Norfolk Island Pine, Araucaria heterophylla, of the South Pacific.

Morphology

Pines are evergreen and resinous. Young trees are almost always conical in shape with many small branches radiating out from a central trunk. In a forest the lower branches may drop off because of lack of sunlight and older trees may develop a flattened crown. In some species and in some environments mature trees can have a branching, twisted form (Dallimore 1966 p 385). The bark of most pines is thick and scaly, but some species have thin, flaking bark.

Foliage

Pines have four types of leaves. Seedlings begin with a whorl of 4-20 seed leaves (cotyledons), followed immediately by juvenile leaves on young plants, 2-6 cm (1 -2 inches) long, single, green or often blue-green, and arranged spirally on the shoot. These are replaced after six months to five years by scale leaves, similar to bud scales, small, brown and non-photosynthetic, and arranged like the juvenile leaves; and the adult leaves or needles, green, bundled in clusters (fascicles) of (1-6) needles together, each fascicle produced from a small bud on a dwarf shoot in the axil of a scale leaf. These bud scales often remain on the fascicle as a basal sheath. The needles persist for 1 to 40 years, depending on species. If a shoot is damaged (e.g. eaten by an animal), the needle fascicles just below the damage will generate a bud which can then replace the lost growth.

Cones

Pines are mostly monoecious, having the male and female cones on the same tree. The male cones are small, typically 1-5 cm (0.4-2 inches) long, and only present for a short period (usually in spring, though autumn in a few pines), falling as soon as they have shed their pollen. The female cones take 1.5-3 years (depending on species) to mature after pollination, with actual fertilization delayed one year. At maturity the cones are 3-60 cm (1-24 inches) long. Each cone has numerous spirally arranged scales, with two seeds on each fertile scale; the scales at the base and tip of the cone are small and sterile, without seeds. The seeds are mostly small and winged, and are anemophilous (wind-dispersed), but some are larger and have only a vestigial wing, and are dispersed by birds or mammals. In others, the fire climax pines, the seeds are stored in closed ("serotinous") cones for many years until a forest fire kills the parent tree; the cones are also opened by the heat and the stored seeds are then released in huge numbers to re-populate the burnt ground.

Classification of Pines

Pines are divided into three subgenera, based on cone, seed and leaf characters:

- Subgenus Strobus (white or soft pines). Cone scale without a sealing band. Umbo terminal. Seedwings adnate. One fibrovascular bundle per leaf.

- Subgenus Ducampopinus (pinyon, lacebark and bristlecone pines). Cone scale without a sealing band. Umbo dorsal. Seedwings articulate. One fibrovascular bundle per leaf.

- Subgenus Pinus (yellow or hard pines). Cone scale with a sealing band. Umbo dorsal. Seedwings articulate. Two fibrovascular bundles per leaf.

File:Pinecandle9872.jpg Young spring growth ("candles") on a Loblolly Pine |

File:Pine cone edit.jpg Monterey Pine cone on forest floor |

A red pine (Pinus resinosa) clearly displaying its roots |

File:Pinien La Brena2004.jpg Mature Pinus pinea (Stone Pine)- note umbrella-shaped canopy |

File:WhitebarkPine 7467t.jpg Whitebark Pine in the Sierra Nevada |

File:Sierra Madre.jpg Hartweg's Pine forest in Mexico |

The bark of a pine in Tecpan, Guatemala. |

File:Pine needles volcanoes guatemala.jpg A pine, probably P. apulcensis, in Guatemala. |

Some important pine species

Pinus pinea - Stone Pine

The Stone Pine (Pinus pinea) is native of southern Europe, primarily the Iberian Peninsula. It has been exploited for its edible pine nuts since prehistoric times. Currently, it is also a widespread horticultural tree, besides being cultivated for the seeds.

The Stone Pine can exceed 25 m height, though is usually rather less tall, 12-20 m being more normal. It has a very characteristic shape, with a short trunk and very broad, smoothly rounded to nearly flat crown. The bark is thick, red-brown and deeply fissured into broad vertical plates. The flexible mid-green leaves are needle-like, in bundles of two, and are 10-20 cm long (exceptionally up to 30 cm). Young trees up to 5-10 years old bear juvenile leaves, which are very different, single (not paired), 2-4 cm long, glaucous blue-green; the adult leaves appear mixed with juvenile leaves from the fourth or fifth year on, replacing it fully by around the 10th year. Juvenile leaves are also produced in re-growth following injury, such as a broken shoot, on older trees.

The cones are broad ovoid, 8-15 cm long, and take 36 months to mature, longer than any other pine. The seeds (pine nuts, piñones or pinoli) are large, 2 cm long, pale brown with a powdery black coating which rubs off easily, and have a rudimentary 4-8 mm wing which falls off very easily. The wing is ineffective for wind dispersal, and the seeds are animal-dispersed, originally mainly by the Azure-winged Magpie, but in recent history, very largely by Humans.

The original range Stone Pine was probably only in Portugal and Spain, but it has been cultivated extensively for at least 6,000 years for the edible seeds. These have been trade items since early historic times. It is cultivated and often naturalised throughout the Mediterranean region, for so long that it is often considered native, while more recently (since about 1700) been introduced to other areas with Mediterranean climates. It is now naturalised in South Africa (where it is listed as an invasive species) and commonly planted in California, Australia, and western Europe north to southern Scotland. Small specimens are grown in large planters or are used for Bonsai, and year-old seedlings are also widely sold as 20-30 cm tall table-top christmas trees.

The Stone Pine has also been called Italian Stone Pine, European Nut Pine, Umbrella Pine (not to be confused with the Japanese Umbrella-pine) and Parasol Pine. It has also occasionally been listed under the invalid name Pinus sativa.

Pinus sylvestris - Scots Pine

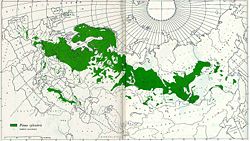

The Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.; family Pinaceae) is a common tree ranging from Great Britain and Spain east to eastern Siberia and the Caucasus Mountains, and as far north as Lapland. In the north of its range, it occurs from sea level to 1000 m, while in the south of its range, it is a high altitude mountain tree, growing at 1200-2500 m altitude.

In the British Isles it is now native only in Scotland, but historical records indicate that it also occurred in Ireland, Wales and England as well until about 300-400 years ago, becoming extinct here due to over-exploitation; it has been re-introduced in these countries. Similar historical extinction and re-introduction applies to Denmark and the Netherlands.

It grows up to 25m in height when mature, exceptionally to 35-40m on a very productive site. The bark is thick, scaly dark grey-brown on the lower trunk, and thin, flaky and orange on the upper trunk and branches. The habit of the mature tree is distinctive due to its long, bare and straight trunk topped by a rounded or flat-topped mass of foliage.

On mature trees the leaves ('needles') are a very attractive blue-green, 3-5 cm long and occur in pairs, but on young vigorous trees the leaves can be twice as long, and occasionally occur in threes and fours on the tips of strong shoots. The cones are pointed ovoid in shape and are 3-7 cm in length.

Over 100 varieties have been described in the botanical literature, but only three are now accepted, the typical var. sylvestris from Scotland and Spain to central Siberia, var. hamata in the Balkans, northern Turkey and the Caucasus, and var. mongolica in Mongolia and adjoining parts of southern Siberia and northwestern China. One other variety, var. nevadensis in southern Spain, may also be distinct.

Scots Pine is the only pine native to northern Europe, forming either pure forests or alongside Norway Spruce, Silver Birch, Common Rowan, Eurasian Aspen and other hardwood species. In central and southern Europe, it occurs with numerous additional species, including European Black Pine, Mountain Pine, Macedonian Pine and Swiss Pine. In the eastern part of its range, it also occurs with Siberian Pine among other trees.

Scots Pine is the National tree of Scotland, and it formed much of the Caledonian Forest which once covered much of the Scottish Highlands. Overcutting for timber demand, fire, overgrazing by sheep and deer, and even deliberate clearance to deter wolves have all been factors in the decline of this once great pine and birch forest. Nowadays only comparatively small areas of this ancient forest remain, the main surviving remnants being Glen Affric, Rothiemurchus, and the Black Wood of Rannoch. Plans are currently in progress to restore at least some areas and work has started at key sites.

The wood is pale brown to red-brown, and used for general construction work. It has a dry density of around 470 kg/m3 (varying with growth conditions), an open porosity of 60%, a fibre saturation point of 0.25 kg/kg and a saturation moisture content of 1.60 kg/kg.

Scots Pine has also been widely planted in New Zealand and much of the colder regions of North America; it is listed as an invasive species in some areas there, including Ontario and Wisconsin.

Pinus densiflora - Japanese Red Pine

The Japanese Red Pine (Pinus densiflora) has a home range that includes Japan, Korea, northeastern China and the extreme southeast of Russia. It has become a popular ornamental and has several cultivars. The height of this tree is 20-35 m. The Japanese red pine prefers full sun on well-drained, slightly acidic soil.

The leaves are needle-like, 8-12 cm long, with two per fascicle. The cones are 4-7 cm long. It is closely related to Scots Pine, differing in the longer, slenderer leaves which are mid green without the glaucous-blue tone of Scots Pine.

In Japan it is known as Akamatsu and Mematsu. It is widely cultivated in Japan both for timber production and as an ornamental tree, and plays an important part in the classic Japanese garden.

Pinus lambertiana - Sugar Pine

The Sugar Pine (Pinus lambertiana) occurs in the mountains of Oregon and California in the western United States, and Baja California in northwestern Mexico; specifically the Sierra Nevada, the Cascade Range, the Coast Ranges, and the Sierra San Pedro Martir.

The Sugar Pine is the largest species of pine, commonly growing to 40-60 m tall, exceptionally up to 81 m tall, and with a trunk diameter of 1.5-2.5 m, exceptionally 3.5 m. It is also notable for having the longest cones of any conifer, mostly 25-50 cm long, exceptionally up to 66 cm long.

The Sugar Pine has been severely affected by the White Pine Blister Rust (Cronartium ribicola), a fungus that was accidentally introduced from Europe in 1909. A high proportion of the Sugar Pine has been killed by the blister rust, particularly in the northern part of the species' range (further south in central and southern California, the summers are too dry for the disease to spread easily). The rust has also destroyed much of the Western White Pine and Whitebark Pine outside of California. The US Forest Service has a program for developing rust-resistant Sugar Pine and Western White Pine. Seedlings of these trees have been introduced into the wild.

Pinus longaeva - Great Basin Bristlecone Pine

The Great Basin Bristlecone Pine (Pinus longaeva) is one of the bristlecone pines, a group of three species of pine found in the higher mountains of the southwest United States. Great Basin Bristlecone Pine occurs in Utah, Nevada and eastern California. In California, it is restricted to the White Mountains, the Inyo Mountains, and the Panamint Range, in Mono and Inyo counties. In Nevada, it is found in most of the higher ranges of the Basin and Range from the Spring Mountains near Las Vegas north to the Ruby Mountains, and in Utah, northeast to South Tent in the Wasatch Range.

It is a medium-size tree, reaching 5-15 m tall and with a trunk diameter of up to 2.5 m, exceptionally 3.6 m diameter. The bark is bright orange-yellow, thin and scaly at the base of the trunk. The leaves ('needles') are in fascicles of five, stout, 2.5-4 cm long, deep green to blue-green on the outer face, with stomata confined to a bright white band on the inner surfaces. The leaves show the longest persistence of any plant, with some remaining green for 45 years (Ewers & Schmid 1981).

The cones are ovoid-cylindrical, 5-10 cm long and 3-4 cm broad when closed, green or purple at first, ripening orange-buff when 16 months old, with numerous thin, fragile scales, each scale with a bristle-like spine 2-5 mm long. The cones open to 4-6 cm broad when mature, releasing the seeds immediately after opening. The seeds are 5 mm long, with a 12-22 mm wing; they are mostly dispersed by the wind, but some are also dispersed by Clark's Nutcrackers, which pluck the seeds out of the opening cones. The nutcrackers uses the seeds as a food resource, storing many for later use, and some of these stored seeds are not used and are able to grow into new plants. However, in many stands current reproduction is not adequate to replace old and dying trees.

It differs from the Rocky Mountains Bristlecone Pine in that the needles always have two resin canals, and these are not interrupted and broken, so it lacks the characteristic small white resin flecks appearing on the needles in that species. From the Foxtail Pine, it differs in the cone bristles being over 2 mm long, and the cones having a more rounded (not conic) base.

The oldest known tree in the world is a specimen of this species located in the White Mountains, with an age of 4,700 years, measured by annual ring count on a small core taken with an increment borer. It bears the nickname "Methuselah". An older specimen, nicknamed "Prometheus", was cut down in 1964.

Pinus radiata - Monterey Pine or Radiata Pine

|

Pinus radiata (family Pinaceae) is known in English as Monterey Pine in some parts of the world (mainly in the USA, Canada and the British Isles), and Radiata Pine in others (primarily Australia, New Zealand and Chile). It is a species of pine native to coastal California in three very limited areas in Santa Cruz, Monterey and San Luis Obispo Counties, and (as the variety Pinus radiata var. binata) on Guadalupe Island and Cedros Island off the west coast of Baja California, Mexico. It is also extensively cultivated in many other warm temperate parts of the world.

P. radiata grows to between 15-30 m in height in the wild, but up to 60 m in cultivation in optimum conditions, with upward pointing branches and a rounded top. The leaves ('needles') are bright green, in clusters of three (two in var. binata), slender, 8-15 cm long and with a blunt tip. The cones are 7-17 cm long, brown, ovoid (egg-shaped), and usually set asymmetrically on a branch, attached at an oblique angle. The bark is fissured and dark grey to brown.

It is closely related to Bishop Pine and Knobcone Pine, hybridizing readily with both species; it is distinguished from the former by needles in threes (not pairs), and from both by the cones not having a sharp spine on the scales.

Ecology

In the wild, Monterey Pine in California is seriously threatened by an introduced fungal disease, Pine Pitch Canker, caused by Fusarium circinatum, while var. binata on Guadalupe Island is critically endangered (less than 100 surviving trees) by uncontrolled grazing by goats released long ago on this uninhabited island.

The forests associated with Monterey Pine are associated with other flora and fauna of note. In particular, the pine forest in Monterey, California was the discovery site for Hickman's potentilla, an endangered species. Piperia yadonii, a rare species of orchid is endemic to the same pine forest adjacent to Pebble Beach. Nearby in a remnant pine forest of Pacific Grove, is a prime wintering habitat of the Monarch butterfly [1].

Cultivation and uses

It is a fast-growing tree, adaptable to a broad range of soil types and climates, though does not tolerate temperatures below about -15°C. Its fast growth makes it ideal for forestry; in a good situation, P. radiata can reach its full height in 40 years or so. It was first introduced into New Zealand in the 1850s; today, over 90% of the country's plantation forests are of this species. This includes the Kaingaroa Forest on the central plateau of the North Island which is the largest planted forest in the world. Australia also has massive Radiata Pine plantations; so much so that many Australians are concerned by the resulting loss of native wildlife habitat. A few native animals, however, thrive on P. radiata, notably the Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoo which, although deprived of much of its natural diet by massive habitat alteration, feeds on P. radiata seeds. P. radiata has also been introduced to the Valdivian temperate rain forests of southern Chile, where vast plantations have been planted for timber, again displacing the native forests.

In areas such as New Zealand this tree has become naturalized, and is considered a weed in the native forest habitat where it has escaped from plantations.

Uses

Pines are commercially among the most important of species used for timber in temperate and tropical regions of the world. Many are grown as a source of wood pulp for paper manufacture. This is because they are fast-growing softwoods that can be planted in relatively dense stands, and because their acidic decaying needles may inhibit the growth of other competing plants in the cropping areas. A typical example is Pinus radiata. The resin of some species is important as the source of turpentine. Some species have large seeds, called pine nuts, that are harvested and sold for cooking and baking. Some pines are used for Christmas trees, and pine cones are also widely used for Christmas decorations. Many pines are also very attractive ornamental trees planted in parks and large gardens. A large number of dwarf cultivars have been selected, suitable for planting in smaller gardens.

Pine plantations can be at risk of fire damage because pine resin is flammable to the point of a tree being explosive under some conditions.

Pine trees are also famous for their pleasant smell, but some people find the smell overbearing. A very small number of people are allergic to pine resin and its scent can trigger an asthma attack. What makes this particularly unusual is that it is also a treatment for asthma in some forms of alternative medicine.

Nutritional use

Pines are well-known survival food plants. The soft, moist, white inner bark, or cambium, found clinging to the dead, woody outer bark is edible and very high in vitamins A and C. It can be eaten in slices raw as a snack or dried and ground up into a powder for use as a thickener/flavoring in stews, soups, and other foods. The bunches of young green cones found at the ends of branches make a healthy hiking snack. A tea made by steeping young, green pine needles in boiling water (known as "strunt" in Sweden) is high in vitamins A and C.

Inspiration

Robert Lovett, the founder of the Lovett Pinetum in Missouri, USA writes:

- However, there are special physical qualities of this genus. It has more species, geographic distribution and morphologic diversity than any of the other gymnosperms, with more tendency for uniquely picturesque individuals than, say, spruces and firs. The pines have oils that transpirate through their needle stomata and evaporate from sap resin in wounds and growing cones which provides a pleasant fragrance unmatched by other genera. Many of them have edible seeds that provide an essential link in the ecology of their habitats. A special sound when the wind blows through their needles, a special sun and shadow pattern on the ground under a pine tree ------that sort of stuff which sounds pretty corny but which has long been a source of inspiration for poets, painters, and musicians. Some of this veneration really does relate to their unique physical beauty and longevity. They are a symbol of long life and beauty in much of the Far East, sacred to Zeus and the people of ancient Corinth, worshiped in Mexico and Central America and an object of affection for early American colonists. Longfellow wrote "we are all poets when we are in the pine woods." (Lovett 2006 p 13).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dallimore, W. & Jackson, A.B. revised by Harrison, S.G., 1967, A Handbook of Coniferae and Ginkgoaceae, New York : St. Martin's Press

- Earle, C.J., 2006, The Gymnosperm Database, Website[2]

- Farjon, A. 1984, 2nd edition 2005. Pines. E. J. Brill, Leiden. ISBN 90-04-13916-8

- Lanner, R.M., 1999, Conifers of California,Los Alivos, California : Cachuma Press ISBN 0962850535

- Little, E. L., Jr., and Critchfield, W. B. 1969. Subdivisions of the Genus Pinus (Pines). US Department of Agriculture Misc. Publ. 1144 (Superintendent of Documents Number: A 1.38:1144).

- Lovett, R., The Lovett Pinetum Charitable Foundation, 2006, Website [3]

- Miller, L., 2006, The Ancient Bristlecone Pine, Website [4]

- Mirov, N. T. 1967. The Genus Pinus. Ronald Press, New York (out of print).

- Peterson, R., 1980, The Pine Tree Book, New York : The Brandywine Press ISBN 0896160068

- Richardson, D. M. (ed.). 1998. Ecology and Biogeography of Pinus. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 530 p. ISBN 0-521-55176-5

External links

- Classification of pines

- Arboretum de Villardebelle Images of cones of selected species

- Gymnosperm Database - Pinus

- Gymnosperm families - scroll down to the Pinaceae

| Links to other Pinaceae genera |

| Pinus | Picea | Cathaya | Larix | Pseudotsuga | Abies | Cedrus | Keteleeria | Pseudolarix | Nothotsuga | Tsuga |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.