Orchid

| Orchids | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

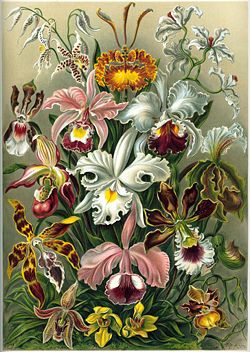

Color plate from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur of 1899 | ||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Subfamilies | ||||||||||

|

Orchids (Orchidaceae family) are the largest and most diverse of the flowering plant families, with over eight hundred described genera and 25,000 species. There are also over 100,000 hybrids and cultivars produced by horticulturalists, created since the introduction of tropical species to Europe.

Orchids have a reputation for beauty and mystery and have long been cultivated. Orchid growing is a popular hobby worldwide and also an important industry. One orchid, vanilla, itself supports a major industry.

Orchids get their name from the Greek orchis, meaning "testicle," from the appearance of subterranean tuberoids of the genus Orchis. The word "orchis" was first used by Theophrastos in his book "De historia plantarum" (The natural history of plants). He was a student of Aristotle and is considered the father of botany and ecology.

General description

Orchids, like the grasses and the palms that they resemble in some ways—for instance the form of their leaves—are monocotyledons. They have one cotyledon, or embryo leaf, in contrast to the two of most flowering plants.

Orchids are found on all continents except Antarctica. The great majority are to be found in the tropics, mostly Asia, South America, and Central America. Some are found above the Arctic Circle, in southern Patagonia, and even on Macquarie Island, close to Antarctica.

The following list gives a rough overview of their distribution:

- Eurasia: 40–60 genera

- North America: 20–30 genera

- tropical America: 300–350 genera

- tropical Africa: 125–150 genera

- tropical Asia: 250–300 genera

- Oceania: 50–70 genera

Orchids can be grouped according to the way they retrieve nutrients:

- A majority of species are perennial epiphytes (growing upon or attached to another living plant). They are found in tropical moist broadleaf forests or mountains and subtropics. These are anchored on other plants, mostly trees, sometimes shrubs. However, they are not parasites.

- A few are lithophytes, similar to epiphytes but growing naturally on rocks or on very rocky soil. Epiphytes and lithophytes derive their nutrients from the atmosphere, rain water, litter, humus, and even their own dead tissue.

- Others are terrestrial plants. They grow in the soil and obtain their nutrients from the soil. This group includes nearly all temperate orchids.

- Some lack chlorophyll and are myco-heterotrophs. These achlorophyllous orchids have an ectomycorrhizal relationship, i.e. they are completely dependent on soil fungi feeding on decaying plant matter (usually fallen leaves) to provide them with nutrients. Typical examples include the Bird's-nest Orchid (Neottia nidus-avis) and Spotted Coral-root (Corallorrhiza maculata).

Most advanced orchids have these five basic features:

- The presence of a column, also called gynostemium

- The flower is bilaterally symmetric.

- The pollen are glued together into the pollinia, a mass of waxy pollen on filaments.

- The seeds are microscopically small, lacking endosperm (food reserves) in the overall majority of the species. There are notable exceptions, such as Disa cardinalis, whose seeds may grow to a length of 1.1 millimeters. Seeds of Vanilla may weigh 20 times or more that of other orchids.

- The seeds can, under natural circumstances, only germinate in symbiosis with specialized fungi. Under artificial circumstances, however, germination is possible "in vitro" on sterile substrates of agar in specialized laboratories. Germinating seeds in agar, usually done in flasks, is an advanced technique, requiring sterility at all costs. It takes anywhere from one up to five to ten years for an orchid seedling to mature. An alternative artificial germination, however, is done by cultivating the fungus and sowing the seeds on them. This is called in-vitro symbiotic culture and is used most commonly for terrestrial orchids.

Leaves

Orchids have simple leaves with parallel veins. Their shape is highly variable between species. Their size and shape can be an aid in identifying the orchid, since it reflects the taxonomic position. The leaves can be enormous or minute, or they can even be lacking (as in the Ghost Orchid (Dendrophylax lindenii), a mycoheterotrophic species, and Aphyllorchis and Taeniophyllum, which depend on their roots, which contain chlorophyll, for photosynthesis).

The structure of the leaves corresponds to the specific habitat of the orchid. Species that typically bask in sunlight, or grow on sites that can be occasionally very dry, have thick, leathery leaves. The laminas are covered by a waxy cuticle to retain water. Shade species, on the other hand, have tall, thin leaves. They cannot tolerate a drop in atmospheric humidity or exposure to direct sunlight. Between these two extremes, there is a whole range of intermediate forms.

The leaves of most orchids live for several years. Some species shed their aged leaves annually and grow new ones.

The leaves of some species can be most beautiful. The leaves of the Macodes sanderiana, a semiterrestrial or lithophyte, show a sparkling silver and gold veining on a light green background. The cordate leaves of Psychopsiella limminghei are light brownish green with maroon-puce markings, created by flower pigments. The attractive mottle of the leaves of Lady's Slippers from temperate zones (Paphiopedilum) is caused by uneven distribution of chlorophyll. Also Phalaenopsis schilleriana is a lovely pastel pink orchid with leaves spotted dark green and light green. The Jewel Orchid (Ludisia discolor) is grown more for its colorful leaves than its fairly inconspicuous white flowers.

Stem

The stem of an orchid determines the habit of the species. Each type of stem can grow in one of these two ways:

- monopodial ("one-footed") growth. The new shoots grow upwards from a single stem, originating in the end bud of the old shoots. It then produces leaves and flowers along this stem. The stem of these orchids can reach a length of several meters (as in the genera Vanda and Vanilla).

- sympodial ("many-footed") growth. The plant produces a series of adjacent shoots that grow to a certain size, bloom, and then stop growing, to be replaced by the next growth. Plants of this type grow laterally rather than vertically, following the surface of their support. The growth continues by development of new leads (with their own leaves and roots) sprouting from or next to those of the previous year (as in the genus Cattleya). While this lead is developing, the rhizome may start its growth again, this time from an 'eye,' or undeveloped bud, thereby causing the rhizome to branch.

Plant thallus and roots

All orchids are perennial herbs, lacking any permanent woody structure.

- Some orchids are terrestrial, growing rooted in the soil. Terrestrial orchids may be rhizomatous, forming corms or tubers. These act as storage organs for food and water. The root caps of terrestrials are smooth and white. Terrestrials are mostly found in colder climates.

- A great many orchids are epiphytes, which do not require soil and use trees for support. They occur in warmer regions. Epiphytic orchids have modified aerial roots and, in the older parts of the root, an epidermis modified into a spongy, water-absorbing velamen, which can have a silvery-gray, white, or brown appearance. The cells of the root epidermis grow at a right angle to the axis of the root. This allows them to get a firm grasp on their support. These roots can sometimes be a few meters long, in order to take up as much moisture as possible. Nutrients mainly come from animal droppings on their supporting tree that are washed down when it rains.

- Several species are lithophytes, growing on rocks. They are found especially in rocky mountain ranges in Australia and Tasmania, central Brazil and Africa.

The base of the stem of sympodial epiphytes, or in some species essentially the entire stem, may be thickened to form what is called a pseudobulb. These contain nutrients and water for drier periods. Pseudobulbs have a smooth surface with lengthwise grooves. They typically stay alive for five or six years. On the inside, they look more like a corm (short, vertical, swollen underground stem of a plant that serves as a storage organ) than the embryonal stage of leaf sheaths. They have different sizes and shapes. They can be conical or oblong. In the Black Orchids (Bulbophyllum), the pseudobulbs are no longer than 2 millimeters. The largest orchid in the world, the Giant Orchid (Grammatophyllum speciosum), has pseudobulbs with lengths of 2–3 meters. When the orchid has aged and the pseudobulb has shed its leaves, the pseudobulb becomes dormant and is called a backbulb. The next year's pseudobulb then takes over, exploiting the last reserves of the backbulb. Eventually, the backbulb also dies off, having given life to newer growths. At the end of the pseudobulb typically appear one or two leaves, though there may be up to a dozen or more. Some Dendrobium have long, canelike pseudobulbs with short, rounded leaves over the whole length. Some orchids have hidden or extremely small pseudobulbs hidden completely inside leaves.

Some sympodial terrestrials, such as Orchis and Ophrys, have two subterranean tubers (more like tuberous roots) between the roots. One is used as a food reserve for wintry periods, and provides for the development of the other pseudobulb, from which visible growth develops.

In warm and humid climates, many terrestrial orchids do not need pseudobulbs.

Orchid flowers

Orchids are most notable to humans for the beauty and variety of their flowers. No plant family has as many different types of flowers as the orchid family.

There are many types of specializations within the Orchidaceae. Best known are the many structural variations in the flowers that encourage pollination by particular species of insects, bats, or birds.

Most African orchids are white, while Asian orchids are often multicolored. Some orchids only grow one flower on each stem, others sometimes more than a hundred together on a single spike.

The typical orchid flower is zygomorphic, i.e. bilaterally symmetric. Notable exceptions are the genera Mormodes, Ludisia, and Macodes.

The flowers grow on racemes or panicles. These can be:

- basal (i.e. produced from the base of the pseudobulb, as in Cymbidium)

- apical (i.e. produced from the apex of the orchid, as in Cattleya)

- or axillary (i.e. coming from a node between the leaf axil and the plant axis, as in Vanda).

The basic orchid flower is composed of three sepals in the outer whorl, and three petals in the inner whorl. A sepal is an individual unit of the outer part of a flower, with the units usually differentiated into petals and sepals. The term ‘tepal’ is usually applied when the petals and sepals are not differentiated. However, in a "typical" flower the sepals are green and lie under the more conspicuous petals. When the flower is in bud, the sepals enclose and protect the more delicate floral parts within. The medial petal is usually modified and enlarged (then called the labellum or lip), forming a platform for pollinators near the center of the corolla. Together, except the lip, they are called tepals.

Sepals form the exterior of the bud. They are green in this stage, but sometimes, if the orchid blossom is, for example, purple, the buds can show a purple tint. When the flower opens, the sepals become intensely colored. Sepals may mimic petals such as in some phalaenopsis, or be completely distinct. In many orchids, the sepals are mutually different and generally resemble the petals. It is not always easy to distinguish sepals and petals. The normal form can be found in Cattleya, with three sepals forming a triangle. But in Venus Slippers (Paphiopedilum) the lower two sepals are concrescent (fused together into a synsepal), while the lip has taken the form of a slipper. In Masdevallia all the sepals are fused into a calyx. In an example like this, the sepals are very prominent, especially in lycaste orchids, the actual petals become diminished and inconspicuous.

The reproductive organs in the center (stamens and pistil) have adapted to become a cylindrical structure called the column or gynandrium. On top of the column lies the stigma, the vestiges of stamens and the pollinia, a mass of waxy pollen on filaments. These filaments can be a caudicle (as in Habenaria) or a stipe (as in Vanda). These filaments hold the pollinia to the viscidium (sticky pad). The pollen are held together by the alkaloid viscine. This viscidium adheres to the body of a visiting insect. The type of pollinia is useful in determining the genus. On top of the pollinia is the anther cap, preventing self-pollination. At the upper edge of the stigma of single-anthered orchids, in front of the anther cap, is the rostellum, a slender beaklike extension.

Reproduction

The variety and the refinement of orchids' reproductive methods are truly amazing. On many orchids, the lip (labellum) serves as a landing pad for flying insects. The labellum is sometimes adapted to have a color and shape that attracts particular male insects via mimicry of a receptive female insect. Some orchids are reliant solely on this deception for pollination.

- The Lady's Slipper (Paphiopedilum) has a deep pocket that traps visiting insects, with just one exit. Passage through this exit leads to pollinia being deposited on the insect.

- Many neotropical orchids are pollinated by male orchid bees, which visit the flowers to gather volatile chemicals they require to synthesize pheromonal attractants. Each type of orchid places the pollinia on a different body part of a different species of bee, so as to enforce proper cross-pollination.

- Eurasian genus Ophrys has some species that look and smell so much like female bumblebees that male bees flying nearby are irresistibly drawn in and attempt to mate with the flower, such as with the Bumblebee Orchid (Ophrys bombyliflora). The viscidium, and thus pollinia, stick to the head or the abdomen of the bumblebee. On visiting another orchid of the same species, the bumblebee pollinates the sticky stigma with the pollinia. The filaments of the pollinia have, during transport, taken such position that the waxy pollen are able to stick in the second orchid to the stigma, just below the rostellum. Such is the refinement of the reproduction. If the filaments had not taken the new position on the bee, the pollinia could not have pollinated the original orchid. Other species of Ophrys are mimics of different bees or wasps, and are also pollinated by males attempting to mate with the flowers, and other orchid genera practice similar deception.

- An underground orchid in Australia, Rhizanthella slateri, never sees the light of day, but depends on ants and other terrestrial insects to pollinate it.

- Many Bulbophyllum species stink like rotting carcasses, and the flies they attract assist their reproduction.

- Catasetum saccatum, a species discussed briefly by Darwin actually launches its viscid pollen sacs with explosive force, when an insect touches a seta. He was ridiculed for suggesting this by the naturalist Thomas Huxley.

- Some Phalaenopsis species in Malaysia are known to use subtle weather cues to coordinate mass flowering.

- Some Phalaenopsis, Dendrobium, and Vanda species produce keiki, offshoots or plantlets formed from one of the nodes along the stem, through the accumulation of growth hormones at that point.

- The filaments of the pollinia of some orchids dry up if they have not been visited by an insect. This way, the waxy pollen falls on the stigma causing the orchid to self-fertilize.

Fruits and seeds

If pollination was successful, the sepals and petals fade and wilt but they remain attached to the ovary. The ovary typically develops into a capsule with three or six longitudinal slits, remaining closed at both ends. The ripening of a capsule can take 2–18 months. The microscopic seeds are very numerous (over a million per capsule in most species). They blow off after ripening like dust particles or spores, barely visible to the human eye. Since they lack endosperm, they must enter symbiotic relationship with mycorrhizal fungi to germinate. These fungi provide the necessary nutrients to the seeds.

All species rely upon mycorrhizal associations with various fungi, mostly genus Rhizoctonia (class Basidiomycetes), for at least part of their life cycle. Some achlorophyllous (lacking chlorophyll) species are adapted to be entirely dependent upon these fungi for nutrients. The fungi decompose surrounding matter, freeing up water-soluble nutrients. Because most orchid seeds are extremely tiny with no food reserves (endosperm lacking), they will not germinate without such a symbiont to supply nutrients in the wild. Some fungi continue to live in the roots of the adult orchid. This enables an orchid such as Neottia nidus-avis to function without chlorophyll. The chance for a seed to meet a fitting fungus is very small. Of all the seeds released, only a minute fraction grow into new orchids.

Horticultural techniques have been devised for germinating seeds on a nutrient-containing gel, eliminating the requirement of the fungus for germination, and greatly aiding the propagation of rare and endangered species.

Orchid cultivation

Orchids have been cultivated for over three thousand years, starting in China. However, modern orchid cultivation started in the Netherlands in the late 1600s when tropical species were brought back on ships from the Far East and the New World. After a long period of trail and error, Europeans learned how to cultivate tropical orchids. One important point was, and still is, understanding the natural climate and conditions of each species' native habitat and trying to duplicate them.

By 1802 orchids were being raised from seed and in 1856 the first artificially produced hybrid orchid bloomed. In the years that followed many new hybrids were created and the cultivation of orchids has become a popular hobby worldwide. The growing of orchid plants for hobbyists and also for cut flowers has become an important industry in many countries. Most orchids grown and sold are hybrids.

Vanilla

Vanilla, Vanilla planifolia (and two other Vanilla species less commonly grown), is the only orchid that is grown for food or any other use besides its beauty (with a few minor exceptions). Vanilla was first cultivated in Central America where it was used, like today, as a flavoring. Vanilla cultivation was introduced to other parts of the world in the 1800s and it is now an important crop in much of the tropics. Madagascar is the leading producer, producing three million metric tons (of a world total of 7.3 million metric tons) in 2005.

The Coca-Cola Company is the world's largest user of vanilla. Besides its use as a flavoring, vanilla is also used in fragrances and perfumes.

Vanilla is a very labor-intensive crop to grow, since the flowers have to be pollinated by hand. It is most suited to small family farms.

"I have never in my life seen anything as profitable for smallholders as vanilla," said Steve New, a horticultural adviser working in Uganda.[1]

Conservation

Many wild orchid species are threatened by people collecting them for sale to orchid fanciers and nurseries. Many are also threatened by the destruction of their habitat by logging and forest clearing.

In 1975 a treaty known as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (also known as CITES) went into effect. It has been ratified by over 140 nations. Under its authority, all orchid species are protected for the purposes of international commerce as potentially threatened or endangered in their natural habitat, with most species listed under Appendix II. A number of species and genera are afforded protection under Appendix I, including all of Paphiopedilum and all of Phragmipedium. Many other species are protected by both international and national legislation, while hybrids are specifically exempted.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Batygina, T. B., E. A. Bragina, and E. Vasilyeva. 2003. The reproductive system and germination in orchids. Acta Biol. Cracov. ser. Bot. 45: 21-34.

- Berg Pana, H. 2005. Handbuch der Orchideen-Namen. Dictionary of Orchid Names. Dizionario dei nomi delle orchidee. Ulmer, Stuttgart.

- Kreutz, C. A. J. 2004. Kompendium der Europaischen Orchideen. Catalogue of European Orchids. Landgraaf, Netherlands: Kreutz Publishers,

- Taylor. D. L., and T. D. Bruns. 1997. Ectomycorrhizal mutualism by two nonphotosynthetic orchids, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 4510-4515. (on line).

- Stewart, J. 2000. Orchids. Portland, OR: Timber Press.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.