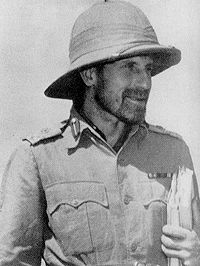

Orde Wingate

Major-General Orde Charles Wingate, Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and two bars, Mentioned-in-Despatches (MID) (February 26, 1903 β March 24, 1944), was a decorated and at times controversial British Army officer and creator of special military units in World War II and Palestine in the 1930s. In 1942 he formed the Chindits, the special forces that penetrated behind Japanese lines in Burma, pioneering the use of air and radio support of troops deep within enemy territory. He has been described as the father of modern guerrilla warfare, although he preferred to see his forces as countering guerrilla action rather than as engaged in this type of warfare. He has also been called father of the Israeli Defense Force. In Israel, he is remembered as "Ha-yedid" (the friend). Less popular with his superiors than with his men, he inspired the loyalty and admiration of the latter.

Perhaps the most important aspect of Wingate's legacy is that his career raised some moral issues that remain of concern in situations involving unconventional warfare. For example, when regular soldiers respond to acts of terror or attacks committed by people who are not members of the official armed forces of a recognized nation-state, what rules of combat apply? The post September 11 2001 "war on terror" raised similar concerns relating to the status of prisoners, how they should be treated, held accountable or put on trial for any alleged war crimes. A man of deep Christian faith, Wingate saw war as a necessary evil. He did not glory in war. He knew that unless fought for a just cause and to defeat evil, war becomes an unnecessary evil. He gave his life in his nation's service when his plane crashed in Burma in 1944.

Childhood and education

Wingate was born February 26, 1903 in Naini Tal, India to a military family. His father had become a committed member of the Plymouth Brethren early in his army career in India, and at the age of 46 married Mary Ethel Orde-Brown, oldest daughter of a family who were also Plymouth Brethren (after wooing her for 20 years).[1] His father reached retirement from the army two years after Wingate was born and he spent most of his childhood in England where he received a very religious upbringing and was introduced to Christian Zionist ideas at a very young age. It was not uncommon for the young Wingate to be subjected to long days of reading and memorizing the Old Testament.[2]

Beside a strict religious upbringing Wingate was also subjected, by his father, to a harsh and Spartan regimen, living with a daily consciousness of hell-fire and eternal damnation. Because of their parents' strict beliefs the family of seven children were kept away from other children and from the influence of the outside world. Until he was 12 years old, Orde had hardly ever mixed with children of his own age.[2]

In 1916, his family having moved to Godalming, Wingate attended Charterhouse School as a day boy. Because he did not board at the school and took no part in sports, he became increasingly separate and isolated, so that he missed out on many of the aspects of a public school (independent school) education of the period. At home, lazing about and idling were forbidden, and the children were always given challenging objectives to encourage independent thought, initiative and self reliance.[3]

Early army career

After four years Wingate left Charterhouse and in 1921 he was accepted into the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, the Royal Artillery's officers' training school. For committing a minor offense against the rules a first year student would be subjected to a ragging ritual named βrunning.β This ritual consisted of the first-year being stripped and forced to run a gauntlet of senior students all of whom wielded a knotted towel which they used to hit the accused on his journey along the line. On reaching the end the first-year would then be thrown into an icy cold cistern of water. When it came time for Wingate to run the gauntlet, for allegedly having returned a horse to the stables too late, he walked to the senior student at the head of the gauntlet, stared at him and dared him to strike. The senior refused. Wingate, moved to the next senior and did the same, he too refused. In turn each senior declined to strike and coming to the end of the line Wingate walked to the cistern and dived straight into the icy cold water.[4]

In 1923 Wingate received his gunnery officer's commission and was posted to the 5th Medium Brigade at Larkhill on Salisbury Plain.[4] During this period he was able to exercise his great interest in horse-riding, gaining a reputation for his skill (and success) in point-to-point races and during fox-hunting, particularly for finding suitable places to cross rivers which earned him the nickname "Otter." It was difficult in the 1920s for an army officer to live on his pay and Wingate, living life to the full, also gained a reputation as a late payer of his bills.[5] In 1926, because of his prowess in riding, Wingate was posted to the Military School of Equitation where he excelled much to the chagrin of the majority of the cavalry officers at the centre who found him insufferable - frequently challenging the instructors in a demonstration of his rebellious nature.[6]

Sudan, 1928β1933

Wingate's father's "Cousin Rex," Sir Reginald Wingate, a retired army general who had been Governor-General of Sudan between 1899 and 1916 and High Commissioner of Egypt from 1917 to 1919, had a considerable influence over Wingate's career at this time. He gave him a positive interest in Middle East affairs and in Arabic. As a result Wingate successfully applied to take a course in Arabic at the School of Oriental Studies in London and passed out of the course, which lasted from October 1926 to March 1927, with a mark of 85 percent.[7]

In June 1927, with Cousin Rex's encouragement, Wingate obtained six months leave in order to mount an expedition in the Sudan. Rex had suggested that he travel via Cairo and then try to obtain secondment to the Sudan Defence Force.[7] Sending his luggage ahead of him, Wingate set off in September 1927 by bicycle, traveling first through France and Germany before making his way to Genoa via Czechoslovakia, Austria and Yugoslavia. Here he took a boat to Egypt. From Cairo he traveled to Khartoum. In April 1928 his application to transfer to the Sudan Defence Force came through and he was posted to The East Arab Corps, serving in the area of Roseires and Gallabat on the borders of Ethiopia where the SDF patrolled to catch slave traders and ivory poachers.[8] He changed the method of regular patrolling to ambushes.

In March 1930 Wingate was given command of a company of 300 soldiers with the local rank of Bimbashi (major). He was never happier than when in the bush with his unit but when at HQ in Khartoum he antagonized the other officers with his aggressive and argumentative personality.[9]

At the end of his tour, Wingate mounted a short expedition into the Libyan Desert to investigate the lost army of Cambyses[10], mentioned in the writings of Herodotus, and to search for the lost oasis of Zerzura. Supported by equipment from the Royal Geographical Society (the findings of the expedition were published on the Royal Geographical Magazine in April 1934[11]) and the Sudan Survey Department, the expedition set off in January 1933. Although they did not find the oasis, Wingate saw the expedition as an opportunity to test his endurance in a very harsh physical environment and also his organizational and leadership abilities.

Return to the UK, 1933

On his return to the UK in 1933, Wingate was posted to Bulford on Salisbury Plain and was heavily involved in retraining, as British artillery units were being mechanized. On the sea journey home from Egypt he had met Lorna Moncrieff Patterson, who was 16 years old and traveling with her mother. They were married two years later, on January, 24 1935.

Palestine and the Special Night Squads

In 1936 Wingate was assigned to the British Mandate of Palestine to a staff office position and became an intelligence officer. From his arrival, he saw the creation of a Jewish State in Palestine as being a religious duty toward the literal fulfillment of prophecy and he immediately put himself into absolute alliance with Jewish political leaders. He believed that Britain had a providential role to play in this process. Wingate learned Hebrew.

Arab guerrillas had at the time of his arrival begun a campaign of attacks against both British mandate officials and Jewish communities, which became known as the Arab Revolt.

Wingate became politically involved with a number of Zionist leaders, eventually becoming an ardent supporter of Zionism, despite the fact that he was not Jewish.[12] He formulated the idea of raising small assault units of British-led Jewish commandos, heavily armed with grenades and light infantry small arms, to combat the Arab uprising, and took his idea personally to Archibald Wavell, who was then a commander of British forces in Palestine. After Wavell gave his permission, Wingate convinced the Zionist Jewish Agency and the leadership of Haganah, the Jewish armed group.

In June 1938 the new British commander, General Haining, gave his permission to create the Special Night Squads, armed groups formed of British and Haganah volunteers. This is the first instance of the British recognizing Haganah's legitimacy as a Jewish defense force. The Jewish Agency helped pay salaries and other costs of the Haganah personnel.

Wingate trained, commanded and accompanied them in their patrols. The units frequently ambushed Arab saboteurs who attacked oil pipelines of the Iraq Petroleum Company, raiding border villages the attackers had used as bases. In these raids, Wingate's men sometimes imposed severe collective punishments on the village inhabitants that were criticized by Zionist leaders as well as Wingate's British superiors. But the tactics proved effective in quelling the uprising, and Wingate was awarded the DSO in 1938.

However, his deepening direct political involvement with the Zionist cause and an incident where he spoke publicly in favor of formation of a Jewish state during his leave in Britain, caused his superiors in Palestine to remove him from command. He was so deeply associated with political causes in Palestine that his superiors considered him compromised as an intelligence officer in the country. He was promoting his own agenda rather than that of the army or the government.

In May 1939, he was transferred back to Britain. Wingate became a hero of the Yishuv (the Jewish Community), and was loved by leaders such as Zvi Brenner and Moshe Dayan who had trained under him, and who claimed that Wingate had "taught us everything we know."[13] He dreamed, says Oren, "of one day commanding the first Jewish army in two thousand years and of leasing the fight to establish an independent Jewish state."[14]

Wingate's political attitudes toward Zionism were heavily influenced by his Plymouth Brethren religious views and belief in certain eschatological doctrines.

Ethiopia and the Gideon Force

At the outbreak of World War II, Wingate was the commander of an anti-aircraft unit in Britain. He repeatedly made proposals to the army and government for the creation of a Jewish army in Palestine which would rule over the area and its Arab population in the name of the British. Eventually his friend Wavell, by this time Commander-in-Chief of Middle East Command which was based in Cairo, invited him to Sudan to begin operations against Italian occupation forces in Ethiopia. Under William Platt, the British commander in Sudan, he created the Gideon Force, a guerrilla force composed of British, Sudanese and Ethiopian soldiers. The force was named after the biblical judge Gideon, who defeated a large force with a tiny band. Wingate invited a number of veterans of the Haganah SNS to join him. With the blessing of the Ethiopian king, Haile Selassie, the group began to operate in February 1941. Wingate was temporarily promoted to lieutenant colonel and put in command. He again insisted on leading from the front and accompanied his troops. The Gideon Force, with the aid of local resistance fighters, harassed Italian forts and their supply lines while the regular army took on the main forces of the Italian army. The small Gideon Force of no more than 1,700 men took the surrender of about 20,000 Italians toward the end of the campaign. At the end of the fighting, Wingate and the men of the Gideon Force linked with the force of Lieutenant-General Alan Cunningham which had advanced from Kenya to the south and accompanied the emperor in his triumphant return to Addis Ababa in May. Wingate was mentioned in dispatches in April 1941 and was awarded a second DSO in December.

With the end of the East African Campaign, on June 4, 1941, Wingate was removed from command of the now-dismantled Gideon Force and his rank was reduced to that of major. During the campaign he was irritated that British authorities ignored his request for decorations for his men and obstructed his efforts to obtain back pay and other compensation for them. He left for Cairo and wrote an official report extremely critical of his commanders, fellow officers, government officials and many others. Wingate was also angry that his efforts had not been praised by authorities, and that he had been forced to leave Abyssinia without having said farewell to Emperor Selassie. Wingate was most concerned about British attempts to stifle Ethiopian freedom, writing that attempts to raise future rebellions amongst populations must be honest ones and should appeal to justice. Soon after, he contracted malaria. He sought treatment from a local doctor instead of army doctors because he was afraid that the illness would give his detractors another further excuse to undermine him. This doctor gave him a large supply of the drug Atabrine, which can produce as a side-effect depression if taken in high dosages.[15] Already depressed over the official response to his Abyssinian command, and sick with malaria, Wingate attempted suicide by stabbing himself in the neck.[12]

Wingate was sent to Britain to recuperate. A highly edited version of his report was passed through Wingate's political supporters in London to Winston Churchill. Consequent to this Leo Amery, the Secretary of State for India contacted Wavell, now Commander-in-Chief in India commanding the South-East Asian Theatre to enquire if there was any chance of employing Wingate in the Far East. On February 27, 1941 Wingate, far from pleased with his posting as a "supernumary major without staff grading" left Britain for Rangoon.[16]

Burma

Chindits and the First Long-Range Jungle Penetration Mission

On Wingate's arrival in March 1942 in the Far East he was appointed colonel once more by General Wavell, and was ordered to organize counter-guerrilla units to fight behind Japanese lines. However, the precipitous collapse of Allied defenses in Burma forestalled further planning, and Wingate flew back to India in April, where he began to promote his ideas for jungle long-range penetration units.[17]

Intrigued by Wingate's theories, General Wavell gave Wingate a brigade of troops, the (Indian 77th Infantry Brigade), from which he created 77 Brigade, which was eventually named the Chindits, a corrupted version of the name of a mythical Burmese lion, the chinthe. By August 1942 he had set up a training center near Gwalior and attempted to toughen up the men by having them camp in the Indian jungle during the rainy season. This proved disastrous, as the result was a very high sick rate among the men. In one battalion 70 percent of the men went absent from duty due to illness, while a Gurkha battalion was reduced from 750 men to 500.[18] Many of the men were replaced in September 1942 by new drafts of personnel from elsewhere in the army.

Meanwhile, his direct manner of dealing with fellow officers and superiors along with eccentric personal habits won him few friends among the officer corps; he would consume raw onions because he thought they were healthy, scrub himself with a rubber brush instead of bathing, and greet guests to his tent while completely naked.[19] However, Wavell's political connections in Britain and the patronage of General Wavell (who had admired his work in the Abyssinian campaign) protected him from closer scrutiny.

The original 1943 Chindit operation was supposed to be a coordinated plan with the field army.[20] When the offensive into Burma by the rest of the army was cancelled, Wingate persuaded Wavell to be allowed to proceed into Burma anyway, arguing the need to disrupt any Japanese attack on Sumprabum as well as to gauge the utility of long-range jungle penetration operations. Wavell eventually gave his consent to Operation Longcloth.[21]

Wingate set out from Imphal on February 12 1943 with the Chindits organized into eight separate columns to cross the Chindwin river.[21] The force met with initial success in putting one of the main railways in Burma out of action. But afterward, Wingate led his force deep into Burma and then over the Irrawaddy River. Once the Chindits had crossed over the river, they found conditions very different to that suggested by intelligence they had received. The area was dry and inhospitable, criss-crossed by motor roads which the Japanese were able to use to good effect, particularly in interdicting supply drops to the Chindits who soon began to suffer severely from exhaustion, and shortages of water and food.[22] On March 22 Eastern Army HQ ordered Wingate to withdraw his units back to India. Wingate and his senior commanders considered a number of options to achieve this but all were threatened by the fact that with no major army offensive in progress, the Japanese would be able to focus their attention on destroying the Chindit force. Eventually they agreed to retrace their steps to the Irrawaddy, since the Japanese would not expect this, and then disperse to make attacks on the enemy as they returned to the Chindwin.[23]

By mid-March, the Japanese had three infantry divisions chasing the Chindits, who were eventually trapped inside the bend of the Shweli River by Japanese forces.[24] Unable to cross the river intact and still reach British lines, the Chindit force was forced to split into small groups to evade enemy forces. The latter paid great attention to preventing air resupply of Chindit columns, as well as hindering their mobility by removing boats from the Irrawaddy, Chindwin, and Mu rivers and actively patrolling the river banks.[25] Continually harassed by the Japanese, the force returned to India by various routes during the spring of 1943 in groups ranging from single individuals to whole columns: some directly, others via a roundabout route from China. Casualties were high, and the force lost approximately one-third of its total strength.[26]

When men were injured, Wingate would leave them "beside the trail" with water, ammunition and a Bible and "often, before the departing troops were out of earshot, they heard the explosion of gunshots from the place where they had left the wounded, who had chosen not to wait for Japanese troops to arrive."[27] His men, however, were deeply loyal.

After-Battle analysis

With the losses incurred during the first long-range jungle penetration operation, many officers in the British and Indian army questioned the overall value of the Chindits. The campaign had the unintended effect of convincing the Japanese that certain sections of the Burma/India Frontier were not as impassable as they previously believed, thus altering their strategic plans. As one consequence, the overall Japanese Army commander in Burma, General Masakazu Kawabe, began planning a 1944 offensive into India to capture the Imphal Plain and Kohima, in order to better defend Burma from future Allied offensives.[28][25]

However, in London the Chindits and their exploits were viewed as a success after the long string of Allied disasters in the Far East theater. Winston Churchill, an ardent proponent of commando operations, was in particular complimentary towards the Chindits and their accomplishments. Afterwards, the Japanese admitted that the Chindits had completely disrupted their plans for the first half of 1943.[25] As a propaganda tool, the Chindit operation was used to prove to the army and those at home that the Japanese could be beaten and that British/Indian Troops could successfully operate in the jungle against experienced Japanese forces. On his return, Wingate wrote an operations report, in which he again was highly critical of the army and even some of his own officers and men. He also promoted more unorthodox ideas, for example that British soldiers had become weak by having too easy access to doctors in civilian life. The report was again passed through back-channels by Wingate's political friends in London directly to Churchill. Churchill then invited Wingate to London. Soon after Wingate arrived, Churchill decided to take him and his wife along to the Quebec Conference. Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Alan Brooke Alanbrooke was astonished at this decision. In his War Diaries Alanbrooke wrote after his interview with Wingate in London on August 4:

"I was very interested in meeting Wingateβ¦. I considered that the results of his form of attacks were certainly worth backing within reasonβ¦. I provided him with all the contacts in England to obtain what he wanted, and told him that on my return from Canada I would go into the whole matter with himβ¦[later] to my astonishment I was informed that Winston was taking Wingate and his wife with him to Canada! It could only be as a museum piece to impress the Americans! There was no other reason to justify this move. It was sheer loss of time for Wingate and the work he had to do in England."[29]

There, Wingate explained his ideas of deep penetration warfare to the Combined Chiefs of Staff meeting on August 17. Brooke wrote on August 17: "Quite a good meeting at which I produced Wingate who gave a first class talk of his ideas and of his views on the running of the Burma campaign"[30] Air power and radio, recent developments in warfare, would allow units to establish bases deep in enemy territory, breaching the outer defenses and extend the range of conventional forces. The leaders were impressed, and larger scale deep penetration attacks were approved.

Second long-range jungle penetration mission

On his return from his meeting with Allied leaders, Wingate had contracted typhoid by drinking bad water on his way back to India. His illness prevented him from taking a more active role in training of the new long-range jungle forces.

Once back in India, Wingate was promoted to acting major general, and was given six brigades. At first, Wingate proposed to convert the entire front into one giant Chindit mission by breaking up the entire 14th Army into Long-Range Penetration units, presumably in the expectation that the Japanese would follow them around the Burmese jungle in an effort to wipe them out.[31] This plan was hurriedly dropped after other commanders pointed out that the Japanese Army would simply advance and seize the forward operating bases of Chindit forces, requiring a defensive battle and substantial troops that the Indian Army would be unable to provide.[31]

In the end, a new long-range jungle penetration operation was planned, this time using all six of the brigades recently allocated to Wingate. This included 111 Brigade, a recently-formed unit known as the Leopards.[26] While Wingate was still in Burma, General Wavell had ordered the formation of 111 Brigade along the lines of the 77 Brigade Chindits, selecting General Joe Lentaigne as the new Commander.[26] 111 Brigade would later be joined by 77 Brigade Chindits in parallel operations once the latter had recovered from prior combat losses.[26]

The second Long-Range Penetration mission was originally intended as a coordinated effort with a planned regular army offensive against northern Burma, but events on the ground resulted in cancellation of the army offensive, leaving the Long-Range Penetration Groups without a means of transporting all six brigades into Burma. Upon Wingate's return to India, he found that his mission had also been canceled for lack of air transport. Wingate took the news bitterly, voicing disappointment to all who would listen, including Allied commanders such as Colonel Philip Cochran of the 1st Air Commando Group, which proved to be a blessing in disguise. Cochran told Wingate that canceling the long-range mission was unnecessary; only a limited amount of plane transport would be needed since, in addition to the light planes and C-47 Dakotas Wingate had counted on, Cochran explained that 1st Air Commando had 150 gliders to haul supplies: Wingateβs dark eyes widened as Phil explained that the gliders could also move a sizable force of troops. The general immediately spread a map on the floor and planned how his Chindits, airlifted deep into the jungle, could fan out from there and fight the Japanese.[32]

With his new glider landing option, Wingate decided to proceed into Burma anyway. The character of the 1944 operations were totally different to those of 1943. The new operations would establish fortified bases in Burma out of which the Chindits would conduct offensive patrol and blocking operations. A similar strategy would be used by the French in Indochina years later at Dien Bien Phu.

On March 6, 1944, the new long-range jungle penetration brigades, now collectively referred to as Chindits, began arriving in Burma by glider and parachute, establishing base areas and drop zones behind Japanese lines. By fortunate timing, the Japanese launched an invasion of India around the same time. By forcing several pitched battles along their line of march, the Chindit columns were able to disrupt the Japanese offensive, diverting troops from the battles in India.

Death

On March 24, 1944 Wingate flew to assess the situations in three Chindit-held bases in Burma. On his return, flying from Imphal to Lalaghat, the US B-25 Mitchell plane in which he was flying crashed into jungle-covered hills near Bishenpur (Bishnupur), in the present-day state of Manipur in Northeast India,[33] where he died alongside nine others. General Joe Lentaigne was appointed to overall command of LRP forces in place of Wingate; he flew out of Burma to assume command as Japanese forces began their assault on Imphal. Command of 111 Brigade in Burma was assigned to Lt. Col. 'Jumbo' Morris, and Brigade Major John Masters.[34]

Eccentricities

Wingate was known for various eccentricities. For instance, he often wore an alarm clock around his wrist, which would go off at times, and a raw onion on a string around his neck, which he would occasionally bite into as a snack. He often went about without clothing. In Palestine, recruits were used to having him come out of the shower to give them orders, wearing nothing but a shower cap, and continuing to scrub himself with a shower brush. Lord Moran, Winston Churchill's personal physician wrote in his diaries that "[Wingate] seemed to me hardly sane - in medical jargon a borderline case."[35] He always carried a Bible.

Commemoration

Orde Wingate was originally buried at the site of the air crash in the Naga Hills in 1944. In April 1947, his remains, and those of other victims of the crash, were moved to the British Military Cemetery in Imphal, India. In November 1950, all the remains were reinterred at Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia in keeping with the custom of repatriating remains in mass graves to the country of origin of the majority of the soldiers.

A memorial to Orde Wingate and the Chindits stands on the north side of the Victoria Embankment, near Ministry of Defence headquarters in London. The facade commemorates the Chindits and the four men awarded the Victoria Cross. The battalions that took part are listed on the sides, with non-infantry units mentioned by their parent formations. The rear of the monument is dedicated to Orde Wingate, and also mentions his contributions to the state of Israel.[36]

To commemorate Wingate's great assistance to the Zionist cause, Israel's National Centre for Physical Education and Sport, the Wingate Institute (Machon Wingate) was named after him. A square in the Rehavia neighborhood of Jerusalem, Wingate Square (Kikar Wingate), also bears his name, as does the Yemin Orde youth village near Haifa.[37] A Jewish football club formed in London in 1946, Wingate F.C. was also named in his honor.

A memorial stone in his honor stands in Charlton Cemetery, London SE7, where other members of the Orde Browne family are buried.

Family

Orde Wingate's son, Orde Jonathan Wingate, joined the Honourable Artillery Company and rose through the ranks to become the regiment's Commanding Officer and later Regimental Colonel. He died in 2000 at the age of 56, and is survived by his wife and two daughters. Other members of the Wingate family live around England.

Legacy

Wingate is credited as having developed modern guerrilla warfare tactics. He used radio and air transport to coordinate his small, highly mobile special units, which he believed could operate for twelve weeks at a time. Davison writes that he was responsible for "important tactical innovations" including "techniques of irregular warfare and effective use of air support in tropical terrain."[38] The Chindits relied on air drops for their supplies. Mead remarks that he is generally acknowledged to have perfected the technique of "maintaining troops without a land line of communication."[39] Mead argues that the official account of World War II is biased against Wingate due to personal animosity between Slim and Wingate, who thought he was too ambitious and obsessed with his own theory that behind-the-lines action was the best strategy to defeat the Japanese.[40] On the one hand, he was "a complex man - difficult, intelligent, ruthless and prone to severe depression." On the other hand, his "military legacy" is "relevant to any military students today."[41]Critics of his campaign in Palestine argue that he blurred the distinction between military personnel and civilians, although he always "stressed that squads should not mistreat β¦ prisoners or civilians." The problem was that the gangs he was fighting against received assistance from civilians.[42] In Israel, he is remembered as "Ha-yedid" (the friend) and considered by some to be the father of the Israeli defense force. He is remembered as "a heroic, larger than life figure to whom the Jewish people" owe "a deep and enduring debt."[43] Oren comments that for every books praising Wingate there is another one that assails him as a "egotist, an eccentric" and "even a madman" Some accuse him of having employed "terror against terror."[44]

Perhaps the most important aspect of Wingate's legacy is that many of the moral issues raised by his career remain of concern in situations involving unconventional warfare. For example, when regular soldiers respond to acts of terror or attacks committed by people who are not members of the official armed forces of a recognized nation-state what rules of combat apply? In the continued conflict between the State of Israel, which Wingate did not live to see established, and members of various para-military groups, these issues remain center stage.[45] Some, such as Moreman, argue that the Chindits were significant mainly in boosting morale not strategically.[46] Others, including Rooney and Dunlop, suggest that they made an important contribution towards the July 1944 defeat of the Japanese in Burma, weakening their position in the jungle.[25][47] As early as 1945, the Chindits were being studied in military training schools.[48] After his death, Wavell compared Wingate with T. E. Lawrence although stressed that the former was more professional.[49] Slim described him as possessing "sparks of genius" and said that he was among the few men in the war who were "irreplaceable."[50] Others have commented on his "supremacy both in planning, training and as a leader." Mead remarks that "there is no evidence that Wingate had personal ambitions".[51] Rather, the appears to have wanted to serve his nation to the best of his ability by using his expertise in irregular combat where it could be the most effective. He saw war as a "necessary evil"[52] When asked by the future Israeli Foreign Secretary what he meant when he called one man bad and another good, he replied, "I mean he is one who lives to fulfill the purposes of God." To Orde Wingate, "good and evil, and the constant struggle between light and darkness in the world and in the heart of man, were β¦ real" and he took this conviction with him into war.[53] At the very least, this suggests that Wingate thought deeply about the morality of war. As the first Chindit expedition left, he concluded his order with "Let us pray God may accept our services and direct our endeavors so that when we shall have done all, we shall see the fruit of our labors and be satisfied." He sometimes cited the Bible in his military communiquΓ©s.[54]

Wingate in fiction

In 1976 the BBC made a three-part drama called Orde Wingate, based on his life, where he was played by Barry Foster. It was made on a limited budget with reduced or stylized settings. It did not attempt to tell the complete story of his life, but presented key episodes in a non-linear way, mainly his time in Palestine but including Burma.[55]

A fictionalized version of Wingate called "P.P. Malcolm" appears in Leon Uris's novel Exodus.[56] He is the hero of Thomas Taylor's Born of war.

Notes

- β David Rooney. Wingate and the Chindits: redressing the balance. (London, UK: Arms and Armour, 1994. ISBN 9781854092045), 13.

- β 2.0 2.1 Rooney, 14.

- β Rooney, 15.

- β 4.0 4.1 Rooney, 17.

- β Rooney, 18, 19.

- β Rooney, 20.

- β 7.0 7.1 Rooney, 21.

- β Rooney, 22β23.

- β Rooney, 23.

- β Lost Army of Cambyses] Archaeology. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- β Rooney, 24, 25.

- β 12.0 12.1 John Masters. The Road past Mandalay, a personal narrative. (New York: Cassell, (1961) 2002. ISBN 0304361577), 161.

- β Aaron Cohen and Douglas Century. 2008. Brotherhood of warriors: behind enemy lines with a commando in one of the world's most elite counterterrorism units. (New York, NY: Ecco. ISBN 9780061236150), 78.

- β Michael B. Oren, "Orde Wingate: Father of the IDF." in David Hazony, Yoram Hazony, and Michael B. Oren. 2006. New essays on Zionism. (Jerusalem, IL: Shalem Press. ISBN 9789657052440), 391.

- β Rooney, 73.

- β Rooney, 75.

- β Rooney, 76.

- β Rooney, 77.

- β Masters, 164.

- β Rooney, 79β80.

- β 21.0 21.1 Rooney, 81.

- β Rooney, 88.

- β Rooney, 91.

- β Masters, 134-135.

- β 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Rooney, 99.

- β 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Masters, 135.

- β Oliver North. War stories II: heroism in the Pacific. (Washington, DC: Regnery Pub., 2004. ISBN 9780895261090), 151.

- β Masters, 155.

- β Alan Brooke Alanbrooke, Alex Danchev, and Daniel Todman. 2002. War diaries, 1939-1945. (London, UK: Phoenix. ISBN 9781842125267), 436, entry for August 4 1943.

- β Alanbrooke, Danchev, and Todman, 443.

- β 31.0 31.1 Masters, 163.

- β John Allison, Phil Cochran, The Most Unforgettable Character I've Met. Special Operations.net. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- β Rooney, 124.

- β Masters, 217-220.

- β Charles McMoran Wilson Moran. 1968. Winston Churchill: the struggle for survival, 1940-1965. (London, UK: Sphere. ISBN 9780722162231), 126.

- β Chindit Memorial, London. Chindits Special Force Burma. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- β Mackubin Thomas Owens, 2004, Wingate's Wisdom: why diplomats blame Israel first. National Review Online. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- β John Davison. 2004. The Pacific war day by day. (St. Paul, MN: Zenith Press. ISBN 9780760320679), 103.

- β Peter W. Mead, "Orde Wingate and the Official Historians." Journal of Contemporary History 14(1) (1979) :55-82. 73.

- β Mead., 66. The War Against Japan series was published by HMSO, London between 1961 and 1965.

- β Davison, 103.

- β Oren, 401.

- β Oren, 391.

- β Oren, 392.

- β Michael Walzer. 1977. Just and unjust wars: a moral argument with historical illustrations. (New York, NY: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465037049), 182.

- β T.R. Moreman. 2005. The jungle, the Japanese and the British Commonwealth armies at war, 1941-45: fighting methods, doctrine and training for jungle warfare. (London, UK: F. Cass. ISBN 9780714649702), 9.

- β Richard Dunlop. 1979. Behind Japanese lines, with the OSS in Burma. (Chicago, IL: Rand McNally. ISBN 9780809485796), 322.

- β Tim Jones. 2001. A special type of warfare: postwar counterinsurgency and the SAS, 1945-52. (London, UK: Frank Cass. ISBN 9780714651750), 15.

- β Mead, 61. Wingate admired Lawrence, see Christopher Sykes. 1959. Orde Wingate. (London, UK: Collins), 132.

- β Mead, 62.

- β Mead, 67.

- β Sykes, 30.

- β L.B. Namier. 1952. Avenues of history. (New York, NY: Macmillan), 180.

- β M. F. Snape. 2005. God and the British soldier: religion and the British Army in the First and Second World Wars. (Christianity and society in the modern world) (London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780415196772), 77.

- β Bill Hays, Barry Foster, James Cosmo, Arnold Diamond, and Denholm Elliott. 2006. Orde Wingate. (Port Washington, NY: Koch Vision. ISBN 9781417228874), 391.

- β Leon Uris. 1958. Exodus. (Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 9780517207987)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allison, John. Phil Cochran, The Most Unforgettable Character I've Met. Special Operations. Retrieved February 21, 2009

- AlanBrooke, Alan Brooke, Alex Danchev, and Daniel Todman. 2002. War diaries, 1939-1945. London, UK: Phoenix. ISBN 9781842125267.

- Bierman, John, and Colin Smith. 1999. Fire in the night: Wingate of Burma, Ethiopia, and Zion. New York, NY: Random House. ISBN 9780375500619.

- Cohen, Aaron, and Douglas Century. 2008. Brotherhood of warriors: behind enemy lines with a commando in one of the world's most elite counterterrorism units. New York, NY: Ecco. ISBN 9780061236150.

- Davison, John. 2004. The Pacific war day by day. St. Paul, MN: Zenith Press. ISBN 9780760320679.

- Dunlop, Richard. 1979. Behind Japanese lines, with the OSS in Burma. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally. ISBN 9780809485796.

- Hays, Bill, Barry Foster, James Cosmo, Arnold Diamond, and Denholm Elliott. 2006. Orde Wingate. Port Washington, NY: Koch Vision. ISBN 9781417228874.

- Jones, Tim. 2001. A special type of warfare: postwar counterinsurgency and the SAS, 1945-52. London, UK: Frank Cass. ISBN 9780714651750.

- Latimer, Jon. 2004. Burma: the forgotten war. London, UK: John Murray. ISBN 9780719565755.

- Masters, John. 1961. The road past Mandalay, a personal narrative. New York, NY: Harper. ISBN 9780304361571.

- Mead, Peter W. 1979. Orde Wingate and the Official Historians. Journal of Contemporary History. 14(1):55-82.

- Moran, Charles McMoran Wilson. 1968. Winston Churchill: the struggle for survival, 1940-1965. London, UK: Sphere. ISBN 9780722162231.

- Moreman, T.R. 2005. The jungle, the Japanese and the British Commonwealth armies at war, 1941-45: fighting methods, doctrine and training for jungle warfare. London, UK: F. Cass. ISBN 9780714649702.

- Namier, L.B. 1952. Avenues of history. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Nath, Prithvi. 1990. Wingate, his relevance to contemporary warfare. New Delhi, IN: Sterling. ISBN 9788120711655.

- North, Oliver. 2004. War stories II: heroism in the Pacific. Washington, DC: Regnery Pub. ISBN 9780895261090.

- Oren, Michael B. "Orde Wingate: Father of the IDF." in David Hazony, Yoram Hazony, and Michael B. Oren. 2006. New essays on Zionism. Jerusalem, IL: Shalem Press. ISBN 9789657052440.

- Rooney, David. 1994. Wingate and the Chindits: redressing the balance. London, UK: Arms and Armour. ISBN 9781854092045.

- Snape, M.F. 2005. God and the British soldier: religion and the British Army in the First and Second World Wars. (Christianity and society in the modern world) London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780415196772.

- Stone, James H. 1969. Crisis fleeting: original reports on military medicine in India and Burma in the Second World War. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General, Dept. of the Army.

- Sykes, Christopher. 1959. Orde Wingate. London, UK: Collins.

- Taylor, Thomas. 1988. Born of war. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780070631922.

- Thomas, Lowell. 1962. Back to Mandalay. London, UK: F. Muller.

- Webster, Donovan. 2005. The Burma Road: the epic story of one of World War II's most remarkable endeavours. London, UK: Pan. ISBN 9780330427036.

- Walzer, Michael. 1977. Just and unjust wars: a moral argument with historical illustrations. New York, NY: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465037049.

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.